"You're All F**ked!" The story behind Marillion's 18th album F.E.A.R.

A band’s 18th album has no right to sound as invigorating, ambitious, angry, emotional and exciting as Marillion’s upcoming F*** Everyone And Run. The band tell Prog all about FEAR

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It’s an early summer morning and Prog is in the Buckinghamshire countryside, where the sound of bees and bird song surrounds the leafy rural business estate Marillion call home. It’s been a while since Prog visited their Racket Club studios and there have been a few changes. The operation is now substantially larger, with office space created in an adjacent unit, and a Kayleighgold disc is disappointingly no longer pinned on a toilet wall.

The challenge for any artist would be to transform such a utilitarian space into one that has the suitably soothing visual dynamic and atmosphere needed for creativity to flourish. The windowless, cramped control room – which in an unadorned state would possess a claustrophobic, cell-like presence – has been suitably transformed in a manner that Changing Rooms’ Laurence Llewelyn-Bowen would approve of. Severe partition walls are painted a striking red and partially covered by oriental curtains, and a considerable amount of material is bunched on the ceiling, giving the room the air of a Mongolian yurt. Scattered among the stacked boxes of leads are candles, Chinese dragons and a gigantic, rocket-shaped lava lamp, with acoustic and bass guitars resting against a wall.

We’re successful enough and have enough resources to be able to do exactly what we want, but we’re not so successful that we can do fucking nothing. We’re still hungry.

The central control panel is surrounded by the late-night detritus of producer Michael Hunter, with an unkempt pile of mints, paper clips, dice, playing cards and vitamin tablets remaining from the recording and mixing sessions that have only just been completed. It feels like the welcoming lounge of a hippie flat, and there’s a certain truth to that. With tough recording deadlines and a penchant for working around the clock, an adjacent store room has the unexpected addition of a double bed, TV and makeshift wardrobe. This, it turns out, is where Hunter has been living over recent weeks, in a lifestyle that brings a fresh perspective to the concept of studio fever and which has given him the look of a man who has been existing in a permanent state of jet lag.

It’s the friendly, bearded face of Hunter who appears to start the playback as Prog settles down at the desk to listen to the freshly completed final master of Marillion’s new album, the startlingly titled Fuck Everyone And Run (FEAR).

There’s already a sense of expectation about this recording. Band members and management have been actively declaring on social media that the album is potentially the finest record they have ever made. Such audacious pronouncements and marketing hype around new releases are to be expected, but as the album progresses, it becomes clear that there’s an unexpected, dazzling truth to those statements.

If you believe the maxim that longer is better, you’ll be happy to hear that three of the five tracks here extend past 15 minutes. They’re lovingly crafted musical journeys that have all the nuances of a ‘classic’ Marillion album. This is the sound of a band with a revived sense of self-respect and belief, defiantly shouting, “We are Marillion and this is what we do,” and not overtly trying to get down with the kids. It’s an all-consuming recording that has an intensity to both the lyrics and the music that is at times overwhelming and emotionally draining. Indeed, after our first listen, Hunter returns to comment on the shocked look in Prog’s eyes, before wryly quipping that having spent well over a year in these confines, he understands more than anyone the effect this music can have.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

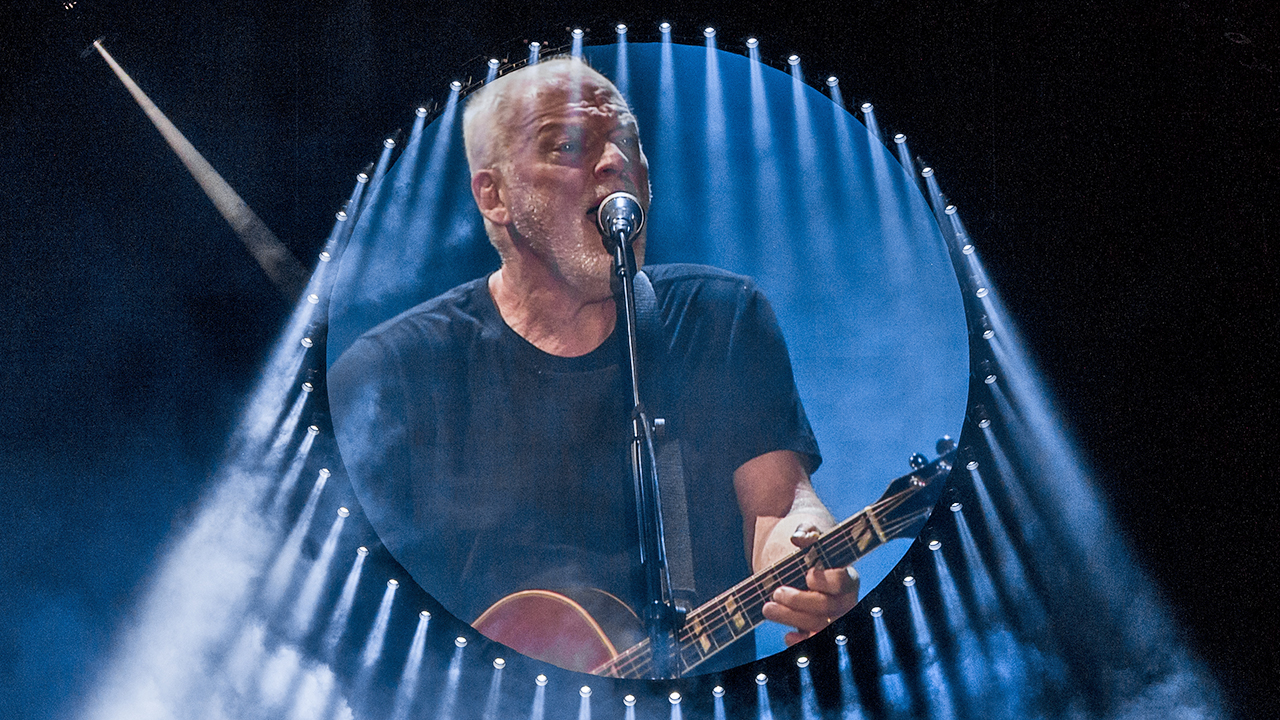

Singer Steve Hogarth is the first of the band to appear, dressed in a leather jacket, Elvis Presley T-shirt and shades, and looking every bit the rock star. He bounces Tigger-like into the control room, warmly embracing Hunter before declaring that this small room was where “all the magic happened”. With the road crew then arriving and starting to remove equipment for the band’s mini-European tour, it’s decided to decamp to a local hotel restaurant for an extended lunch.

Sometimes, being the wrong side of three quarters of a bottle of red makes you make different music.

We’re soon tailing Hogarth’s Mini on narrow country lanes, as he zips around corners at a speed and ease that indicates a familiarity with the route. As he flies around another blind bend, fear suddenly crosses the mind that this piece might end up transforming into a horrific obituary piece, with Prog the first witness on the scene.

Mercifully, the journey is uneventful and short, and we’re soon settling down with the rest of the band in a very English, walled garden restaurant. It’s noticeable how, despite the presence of countless other customers, the band are never once pestered for autographs or photos. They’re successful enough to ensure they can make a healthy living from their music, but without the pitfalls that come with mega-stardom. As keyboard player Mark Kelly wisely describes it, they exist in a “Goldilocks zone”, which few of their peers are fortunate enough to have.

“That’s exactly the point really,” he says. “We’re successful enough and have enough resources to be able to do exactly what we want, but we’re not so successful that we can do fucking nothing. We’re still hungry. It really is that Goldilocks zone. If we were less successful, we’d be put in a position where we had to put more albums out just to keep the money coming in. I’m also sure that if we were far more successful, we probably wouldn’t bother.”

The new album has been four years in the making, a gap that would be financially unsustainable for most acts, but with Marillion’s ongoing cunning plan for financing themselves via pre-order campaigns and their regular conventions, they’ve freed themselves from record label ties and any overbearing time pressure. Such autonomy has enabled their music to grow organically, and the results are striking. Yet the band still haven’t managed to lose the dread of writing new music, and the experiences of creating their last album, Sounds That Can’t Be Made, remained with them as they began writing again.

“Looking back at that last album, I can say it was more fraught with problems – the beginning was really unpleasant and the end was really fraught,” admits Hogarth, before adding with a knowing smile that “the bit in the middle was okay”.

The truncated method of writing and a last-minute panic to complete the recording meant the final parts were being recorded on the road, and nobody in the band had heard the final mixes until they were presented to them as a fait accompli.

“It was one of those situations where we were recording bits and pieces in different places,” recalls Kelly. “When the mixes finally started coming together, we were in hotel rooms trying to listen to the mixes and hearing things that different members of the band had done for the first time. It was like, ‘What’s that? I didn’t know you were going to play that guitar part over my keyboards!’”

With that, guitarist Steve Rothery glances upwards at Kelly and smiles, before adding somewhat dryly, “And vice versa, I might add…”

It’s the kind of banter you would expect from a bunch of mates in a pub on a Friday night, and it’s genuinely refreshing. There are those bands who, to outsiders, appear to be close friends, but are in fact strangers away from the studio or the confines of the tour bus. Indeed, only their inner circle will know if it’s the same with Marillion, but they don’t give that impression, and they still have an easy comfort with each other that ensures conversations flow. Silent, knowing looks are regularly exchanged, and they never pass up an opportunity to gently rib each other. It’s a familiarity that this quintet have built up in the 27 years since Hogarth joined the band, and it has ensured that even though the first few weeks of a writing session are always laden with frustration, they now have enough self-awareness and understanding not to get irritated with each other’s foibles.

“Oh yeah, we’re all completely bonkers, or eccentric in our own way,” admits Rothery with a smile. “But we do forgive each other and if we do fall out these days, it’s always a storm in a teacup really.”

“Certainly, when the pressure is on, we can be a bit snappy with each other,” interjects Kelly, “But generally, we still have fun together, still enjoy each other’s company.”

Hogarth indicates that of all the members of Marillion, he finds the idea of writing the most harrowing. Although the band have now concocted a way of working that over recent years has become relatively straightforward, his anxiety appears to date back to 1991’s Holidays In Eden. The music on their Hogarth-era debut Seasons End had, for the most part, been written prior to the singer joining the band, and it was a painless process to add lyrics and his distinctive vocal phrasings to those recordings.

By the time they needed to record a follow-up, both parties searched for a method that worked, but with the band taking time to jam ideas and Hogarth preferring to take an idea and quickly complete it, the rumours were that the singer needed to take time away to have a long lie down.

“I think I was sent to have a lie down actually,” he chuckles heartily. “There’s a difference. It didn’t help though.”

“That really was the worst time,” suggests drummer Ian Mosley from behind his permanently shaded eyes. “It was when we had a completely blank canvas and we had done the one album with Steve, and a lot of music had been written already for that album anyway. So suddenly we are all sitting in a room together, thinking, ‘What are we supposed to be doing?’”

Over recent years, their methodology has become finely tuned, with the band jamming endlessly for weeks, trying to find those unconsciously created musical nuggets that occasionally rise to the surface. These would be carefully catalogued by Mike Hunter, who would then have the unenviable task of listening to the hundreds of hours of music before identifying a still immense list of ideas he felt had potential. Those segments would then be sent to the band, who would each rank them, and it would be those musical seeds that everyone liked which would be selected for further work.

It’s an unusual way of working, but it seems to eradicate a lot of potential internal tension, especially if there’s a split between musicians over which ideas are worth pursuing. Although preferring to eschew the limelight and apparently not wanting to receive any credit for the work he’s put into the album, the praise for Hunter is unanimous. He is, according to the band, the sixth member of Marillion.

“What shouldn’t be understated in all of this is really how much Mike Hunter put into this,” exclaims Hogarth with conviction. “We write initially by jamming. So there are hours and hours of stuff – probably a lot of which doesn’t even sound like music – that’s recorded, and then he has the job of sitting in his loft and pulling out anything that’s remotely something. Then he’ll play the cream of what he’s got to us, we’ll distil it and all vote on that. So out of that, what might have been 400 hours of stuff, we’ll probably choose 50 ideas.

“Often we would wonder when on earth we had recorded what he was playing us. I’d be like, ‘No, I have no memory of us ever doing that,’ and he’d say, ‘Well it was only last week!’

We’re doing something we deeply believe in and are deeply passionate about, even after all these years. The creativity and the chemistry between the five of us is still as strong as it ever has been.

“Without Mike, my God, one of us would have had to have done that and it really is unenviable. I’ve had files from him at three and four in the morning because he couldn’t sleep and he’s got up and done something.

“I suspect he might have more of a handle on what it is about us that excites people than we do. I mean,

I struggle. It’s great that they get excited, but sometimes I can’t work out what it is and what it is that ingrains itself so deeply in people. We’re not the kind of band that people say, ‘Oh, they’re alright.’ It turns into some kind of lifelong crusade.”

“Working that way does work, and it stops us falling out unnecessarily,” adds bassist Pete Trewavas, who is as amiable in person as his on-stage persona would indicate. “There was so much music that it gave us so many starting points if we stumbled across something we couldn’t agree on. The other thing Mike would do was put sections and bits and pieces together. Sometimes we might be out on tour and he would just mess about and say, ‘Well these are quite nice. What happens if I do something with them?’ We’d come back off tour and he’d play us things and say, ‘I’ve been having a think about this. This is just an idea – what do you think?’ It’s really great to have somebody like that who has got your back.

“In a strange kind of way, because of the way we’re working, we’re becoming more creative because we’re choosing the times that we’re going to do it. If you’re in a room thinking, ‘We’ve got to come up with a song today – everything has been rubbish for the first week, we’ve got to do something,’ it’s just the wrong place to start really.”

One way of alleviating the routine and pressure during the final stages of writing has been for Marillion to traipse 90 miles west from their base to Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios near Bath. The notion behind this is that they’re able to escape the daily routine of life at Racket, a working life that’s almost a nine-to-five existence, with demands at home, as well as the business decisions which need to be made, all interrupting the creative flow.

“We can be like a gang again, rather than a firm of architects, which is how we feel the rest of the time,” claims Hogarth. “Because we kind of manage ourselves as well, along with Lucy [Jordache, Marillion co-manager], we’re part of the decision-making process and there’s an hour or so of every day just doing emails. You know, ‘What do you think about this? Shall we have an argument about that?’ There are so many decisions to be made that aren’t strictly about music, you can feel that you’re no longer in a band and you’ve now got a proper job, which is the reason everybody gets into a band in the first place. So to find yourself back in a proper job through the back door is terrible.”

Picking up on Hogarth’s comment, Mosley briefly interrupts eating his recently served sausages and mash before dryly quipping, “I think you’ll find it’s a long way from a proper job…”

“Yeah, okay, but we do have to get involved,” continues Hogarth, laughing at his gaffe. “So getting off to Real World, we’re all living there and all sleeping there. And the other problem about having your own studio is that, with perhaps the exception of one gin and tonic, you can’t have a drink because you’ve got to drive home at the end of the day. So that’s not very creative in a rock’n’roll sense either. Sometimes, being the wrong side of three quarters of a bottle of red makes you make different music.

“When you’re jamming and playing together, you’re in a slightly different state of mind. So to be able to work late, stop and have dinner, and then go back to the studio space at nine or 10 at night, there’s always a different atmosphere at night to during the day. It pulls us together as a gang and it gets you away from the ‘Oh my God, the drains have just exploded.’ You can leave that with the missus for a week and you can just immerse yourself in the music.

“They’ve got this big screen in the studio at Real World because they do soundtracks for films as well occasionally. So we can drop the big screen in the evening and just put a movie on, with the sound off, and just have that running while we’re jamming. So we’d be in the dark and there would be a vibe going as well.”

- Gong founder Gilli Smyth dead at 83

- Festival sex stats revealed

- Marillion celebrate ability to play without compromise

- 12 Prog Albums We Can't Wait To Get Our Hands On Before The End Of 2016!

The elongated nature of the songs on FEAR will undoubtedly delight many Prog readers, and although the band have gradually returned to writing such monumental material over recent years, to find a majority of the songs extend to the length of their often derided 1982 track Grendel does come as a surprise. One problem facing musicians with a long career is that interview quotes from the past can never be escaped, and lie waiting to be thrown unceremoniously in your face years later. Mark Kelly’s brief departure to the bar proves fortuitous for him, as the band are reminded that he once claimed: “We could do a 15-minute fart into a paper bag and some people would be happier with that than a three-minute classic.” The revelation is met with loud laughter around the table.

“Ah yes, the wisdom of Mark Kelly,” grins Rothery. “You really can’t put a price on that. But the reason for the songs being longer is really down to the lyrics and having the space to tell the story.”

Certainly the issues covered by those lyrics are weighty ones and any attempt to cram them into a three-minute format would be rather crass, rendering them meaningless. The subjects they delve into are worthy of deep exploration, and with the band taking their time to conclude their musical backdrop, that delay allowed Hogarth to expand them further.

“I mean, that’s the frustrating part of my job,” he notes. “I sit looking at a set of words for, like, four years, waiting for somebody to get happy with a chord change so I can sing three lines on something. But on the positive side, having that amount of time does give me a lot of room to ruminate, go over the words again, tear them apart and rearrange them and add things to them. I’m under pressure for those lyrics not to be completely rubbish either, so it’s not just four pounds of words.”

“Steve has these lyrics written in various forms,” adds the recently reseated Kelly, unaware of the gentle ribbing he has been subjected to in his absence. “We’re jamming and throughout the process, Steve is constantly listening and thinking, ‘What does this music feel like? What lyric matches this piece of music?’ Sometimes it works and those moments end up becoming the building blocks for the songs, and over a long time, it comes together.

“There are loads of bits of music with the same lyrics on that haven’t quite captured the moment and haven’t been quite right. So they got left, and what remained was the music that perfectly matched the words, and over time the songs got longer. Better writers would just have gone, ‘We’re going to write the music that perfectly matches the lyrics.’”

Aside from the masterful music, the lyrics are similarly adroit, possessing thought-provoking passages that often venture into the dangerous area of politics. That’s not to suggest Marillion are suddenly turning into Billy Bragg – these are far from unsubtle, chest-beating protest songs – but there are undertones that delve into areas some may find controversial and may vehemently disagree with. They cover Syrian refugees being denied access to Europe, the greed of bankers and oligarchs, Hogarth’s apparent feeling of shame at being British, and a sense of the loss of a nation. Remarkably, many of his words demonstrate an acute perception, given they were written years ago, and are becoming even more relevant and accurate with the passage of time.

We’re not the kind of band that people say, ‘Oh, they’re alright.’ It turns into some kind of lifelong crusade.

“This album really is about a sense of foreboding,” says Hogarth. “What is kind of interesting is that a lot of these words are about three years old. Now we’re all sitting here, post-Brexit, on the day the Chilcot report into the Iraq war comes out. But all these words were on paper years ago and some even date back to unused jams from the last album. So it’s about that foreboding and a feeling that everything is going to change in this country.

“I was trying to paint a picture of someone mowing their lawn in a quiet garden as a storm comes towards them. It’s an ecological storm, a financial storm; it’s a humanitarian storm. It’s a feeling that there’s a sort of watershed coming. I don’t know what it is, but it’s just foreboding. If there’s a central theme to the record, it’s that – plus the fact we brought this on ourselves, and a consequential sense of shame.”

These are weighty issues and the shame Hogarth refers to is palpable. It’s a heartbreaking, internal self-flagellation that has visibly been troubling him, yet the reality is that there’s little the masses, or musicians, can seemingly do to stop those in positions of power. It’s perhaps this realisation that has given rise to a barely contained resentment that surfaces on tracks such as El Dorado and The New Kings. Is Hogarth as internally furious as the lyrics often indicate?

“The New Kings is really a song about how the old systems of democracy have become overwhelmed and compromised by money and corporations,” he explains. “Along with the fact that the gap between rich and poor is widening all the time. There’s also an overall loss of faith in what this country represents to me. I was always quietly very proud of being English, and that went for me with Iraq, and I’ve been quietly ashamed of being English ever since. I find that very hard to forgive that there are certain individuals who took that away from me, and that is one hell of a huge thing to lose.

“The last section of The New Kings is a sister section of El Dorado and is about the romantic notion you believed England to be when you were a kid. There’s so much scope to talk about all the clichés – the bankers, the hideous bonuses that they’re paid for presiding over things that fail. So to answer your question, I guess I’ve got so much simmering resentment at that loss of faith that it produced The New Kings and El Dorado, which are two of the longer songs on the album. El Dorado is similarly themed, along with the fact that there’s a sense of shame over the migrant crisis.”

All of this gives Hogarth the demeanour of a man with the weight of the world on his shoulders. There are passages during these tracks that are clearly immensely personal, describing how he is ‘becoming harder to live with’ and ‘you can’t see into my head’. Such words imply that there’s some degree of inner turmoil that affects not just himself, but those around him. Is that a fair assessment, and why does he put himself through probing such themes if they’re affecting him so deeply? Surely there are other subjects that would be just as creatively fulfilling?

“I’m just not living like I used to, just to have a good time, all the time,” he says, lifting an eyebrow and obviously fully aware he’s just quoted Spinal Tap’s Viv Savage. “You know, as you get old, once you’re 60, you’re not really in a position to live for those ideals. You think, ‘I’m getting on now – if I want to say something, I should make it something important.’ Yes, it does mess with me a bit talking about these things, but I’ve made a lot of records and what am I going to do? Write another record with another eight love songs on it?’ I’m sure someone else will do that. So yes, maybe I should say something important.”

There’s a pause in the conversation, with everyone around the table probably mulling over their own mortality and middle age while silently sipping their drinks. Such maudlin thoughts are only brief, as Mark Kelly attempts to violently dissuade what Prog is reliably informed is a Blandford Fly from leeching on his blood. Seemingly a creature capable of inflicting serious damage on any unaware victim, it’s eventual disappearance allows the keyboard player to comment on his concerns over Hogarth’s lyrical openness, especially those that, superficially at least, appear to delve into his private life.

“We do wonder sometimes, Steve,” says Kelly before silently pondering the wisest choice of words. “Well, it’s quite difficult to say this. You’re quite brave in some of things you say. You say things that are extremely personal and it would make me feel uncomfortable…”

“Only if I was married to him,” deadpans Rothery.

“But there’s also that thing where people think, ‘Oh, he’s just making this up to make a point,’” continues Kelly. “Yet there’s always the thought that people might think you’re talking about yourself, even when you’re not.”

“Well, you know me well enough to know how true they often are,” confesses Hogarth. “That’s part of what I have to deal with really. History has shown me that whenever I’ve done something like that in the past, and thought to myself, ‘God, is this too much?’ people have responded really positively to it.

“The other freedom of expression I have as a lyricist comes from being in this band. I know I can get away with being honest and it won’t terminate our career. For most artists that would be the end. Even bands like U2, there would be a limit to how much Bono could open his mouth politically without damaging their sales base. We’re not in that mainstream so we don’t even have to consider those compromises. Nobody in the band has ever come along to me and said, ‘Are you sure you want to say that?’ I’m quite surprised really.”

However, there does need to be a unanimous consensus within the group that any potential sources of lyrical controversy are worth the trouble. Hogarth may never have been edited or censured, but with certain topics guaranteed to raise hackles, Marillion need to be comfortable with the expressed sentiments. Indeed, the band may not have a reputation for political commentary, but they have had their moments. There was Forgotten Sons on their debut that dealt with the situation in Northern Ireland in the early 80s; a tale of the rise of Austrian fascism during the same decade on White Russian; and most controversially of all, Gaza on their last album. The conviction Hogarth espoused during that song was that, as he puts it now, “a child shouldn’t have to grow up in a place like this”, but even the song title caused alarm in those all too ready to take offence.

“That was something we had to agree was a statement we all wanted to make,” reasons Rothery. “It was a big decision. We all had to stand behind it and in that respect it was probably one of the most important songs we’ve ever written. We knew we would come in for a certain amount of abuse. It was so sad when we posted it online – within days, the comments from both sides became a microcosm of the situation itself. There were these radically opposing viewpoints and there was no possibility of any reconciliation there. The fact that we were even writing a song about Gaza led to this tirade. It was just bizarre.”

“The thing is, if you believe in what you’re saying, it doesn’t really matter,” says Hogarth defiantly. “What does matter is if someone comes back and exposes something that makes you think you were naive. I tried so hard with Gaza not to make it naive rubbish. It was such a hard song to write from the moment I realised the band were hell-bent on putting it on the record. I had to make sure there wasn’t any nonsense in the lyrics that someone who’d just seen a documentary could’ve written. I wasn’t saying it was this person or this country’s fault. I didn’t want to be bashing Israel, or saying anything that would mean I could be perceived as being an anti-Semite. I still was, though, and there were people who called me an anti-Semite before they had even seen the words. So when you’re dealing with that, you can’t win.

“There were those of the Jewish faith who felt – probably rightly – that some white English boy shouldn’t be passing comment. I did worry that here I was, in a leafy part of middle England, eating my salad, talking about how Israel is treating Palestinians on the Gaza Strip. You know, who the fuck am I to be saying that? So yes, it has only been Gaza when we all sat around going, ‘What are we doing here?’ We had to ask ourselves if we were really sure.”

The quandary over the lyrics also extends to their music. They might be 18 albums into their career, but even when they’ve recorded an album as genuinely accomplished as FEAR, there remains an inherent lack of self-belief. It’s not a modesty – fake or genuine – but the band all possess a nagging sensation that the album may not be up to muster. The stresses of that mindset and an approaching deadline meant they, and especially producer Hunter, have been under a certain amount of strain over recent weeks.

“He was nearly off the roof, and very close to the edge, a fortnight ago when the deadline was approaching,” reveals Hogarth. “We were all going, ‘Is he alright?’ because he’s been working so hard as it means so much to him, as it does to all of us. So we were all pretty edgy as the deadline came up. You do reach a point when you think, ‘Is any of this any good?’ There’s a point when you get really excited about something, then that passes and you wonder

if we’re working each other up, convincing ourselves that this is amazing when it isn’t. So it’s always great to get it out into the world and see how people react.”

It does appear, though, that the band do at least accept that there’s an exceptionally high quality to all of the tracks on this album. There are no moment of weakness, no songs where dance beats have been inharmoniously added, and with Prog’s reassurances that this is undoubtedly one of their finest recordings, they become

less guarded.

“I do think there’s a consistency to this album which is unusual,” says Rothery. “There are only a handful of albums where I think we’ve made that happen, which for me are Afraid Of Sunlight, and probably Marbles and Sounds That Can’t Be Made. So this is really up there and at the same time, it has such a broad scope of power to it. Maybe this album is good because we took the time, although that doesn’t have to be the case, as Afraid Of Sunlight came together relatively quickly. I honestly can’t think of any way we could improve that album, which for me is a rare thing to say. There’s no musical uncertainty on this new record, and there’s an embracing of what we are and what we do.”

“For me, there’s usually one song on every album that, and not wishing to be too blunt, I wouldn’t care for and really wouldn’t be unhappy if it got left off,” declares Kelly. “But because we’re a five-piece band and we all have different musical tastes, you agree on the songs that eventually go on an album. For me, this album has five really good songs on it.”

Marillion remain in an enviable position. There are few acts who have been as consistent over the last 35 years, and who have survived and thrived after the loss of a recognisable lead singer. They remain a hugely viable band, with a fiercely loyal fan base, owning their own recording studio and having the ability to record exactly the music they want, without fearing the appearance of a suited A&R man. There are even fewer bands who could even contemplate having their 18th album as one of their finest. To what do they owe their success?

“I think we can afford to do it and that’s part of the secret,” states Hogarth. “The reason a lot of creative artists just stop is because they’re signed to a major label who lose interest if they haven’t had a hit for a couple of albums. We’ve got our own studio and a lot of artists would give their right arm to have a place where they can just go to work, without having to go cap in hand to a label. We’re not millionaires but we stay above water.”

“But it’s also the reason we do it as well,” muses Rothery. “Some people get into music as a career and it’s really nothing to do with the music – it’s just a job they want to do. That’s never been the case with us. We’re doing something we deeply believe in and are deeply passionate about, even after all these years. The creativity and the chemistry between the five of us is still as strong as it ever has been. We can be satisfied with the end result without having to tick any boxes or please the record company. We’re not trying to make records for the radio. We just want to make something that we, the five of us sitting here, enjoy. Hopefully when it gets out in the world, people will enjoy it as well.

“I think for us, with Mike’s help, for us to come up with something so strong for our 18th studio album is quite remarkable. We also wrote a lot more music than we used, and have a lot of great ideas that are on the shelf. It would be good if it didn’t take four years for the next album. If we could do it in two or three maybe.”

Rothery’s final comment provokes a look of horror on Hogarth’s face.

“Well, you knock yourself out Steve, I’ll be with you in 2018,” the singer laughs, standing up and grabbing his sunglasses and car keys from the table. “There’s nothing wrong in it taking two years, just as long as we don’t have to record it in the next two years…”

FEAR is out on September 23. Visit the band’s website for more information.

The Invisible Man

How would Marillion describe producer Michael Hunter?

Pete Trewavas: “‘God’, maybe, or is that too strong? He puts everything into it and he has such a great way with his vision of music.”

Steve Hogarth: “He’s very good at card tricks and does descend into a vagrant during the time of recording. He’s a great catalyst and we would never have made this record without him.”

Mark Kelly: “He’s a talented, miserable fucker but we love him. He’s incredibly hard-working and calling him our George Martin would be doing him a great disservice really, as he’s more than that and not just a producer. He doesn’t want to be credited at all and doesn’t want anyone to know what he’s done because he had a bad experience. In 2007 we made Somewhere Else, and we all went, ‘This is great,’ and loved it. And he got completely torn to pieces by a few fans on the Marillion online forum who didn’t like the album for whatever reason. He took it so personally that he’s shied away since then.”

Steve Rothery: “He’s actually a very funny guy. He’s quite fragile in that respect and doesn’t have the ego of a musician or even of a successful producer. He knows what he believes in and will do his best, but he’s quite a sensitive soul at the same time.”