“It was like we’d climbed the mountain. My head was spinning every time I sang it”: Yes created longer songs than Close To The Edge, but none with as much impact

Classical music, Eastern mysticism and the River Thames came together to inspire the 19-minute title track from their fifth album in 1972

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 2022 the makers of Prog and Classic Rock presented Yes: The Complete Story, a special-edition magazine dedicated to the progressive rock giants and their five-decade history. It included the story of the title track from their definitive 1972 album Close To The Edge.

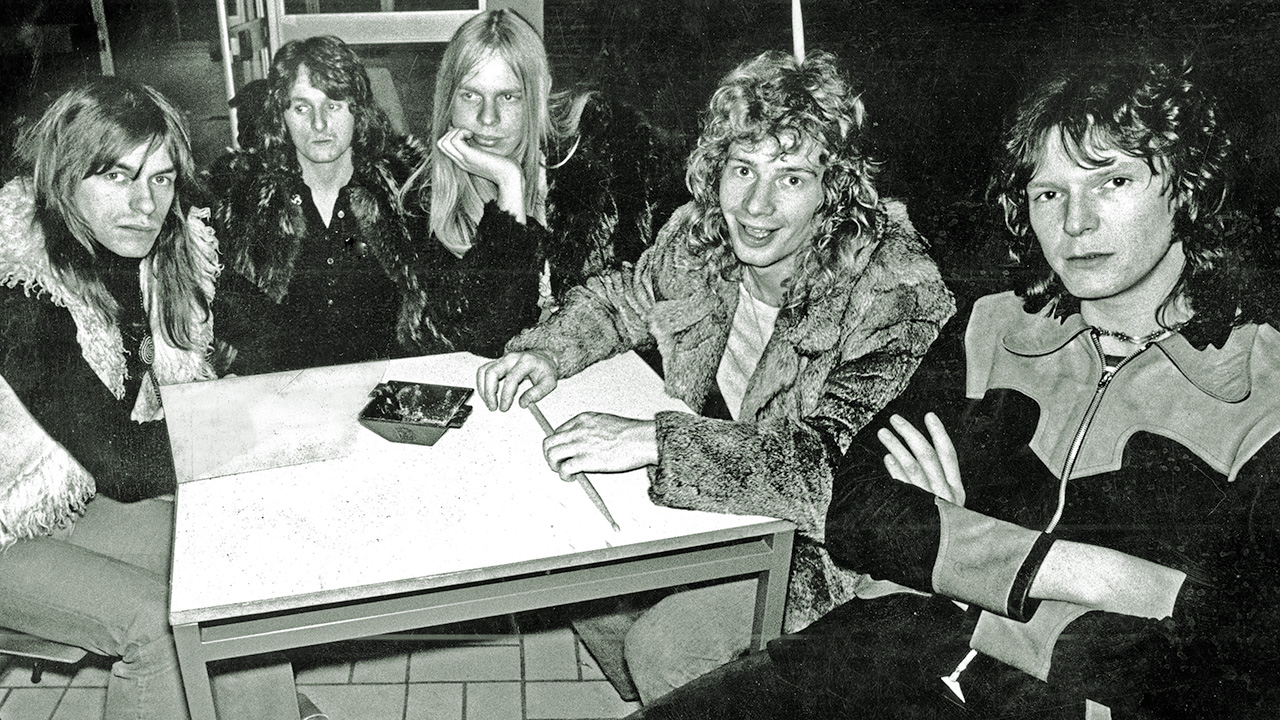

Right from the start, Yes were driven by a desire to push their music toward the grand or epic, through startlingly reimagined cover versions or through their own compositions. Although the likes of Van der Graaf Generator, Caravan, Pink Floyd, ELP and Jethro Tull got there before them, an extended composition had been on Yes’ to-do list for quite a while. “We knew we were going to do a long-form piece, something that would take up the side of an album,” bassist Chris Squire recalled in 2013.

The band had slowly but surely been expanding their chops, hastened by the recruitment of guitarist Steve Howe in 1970 and keyboard maestro Rick Wakeman the following year. The degree of progress can be measured with the complex arrangements in pieces like Yours Is No Disgrace and Starship Trooper from 1970’s The Yes Album, and Heart Of The Sunrise on 1971 follow-up Fragile’. As Squire put it: “Heart Of The Sunrise had really been the germination of that idea where you had different sections with contrasting flavours all working together.”

That vision came to fruition on fifth album Close To The Edge. The song was divided into four parts – I. The Solid Time Of Change, II: Total Mass Retain, III. I Get Up, I Get Down and IV: Seasons Of Man – running to a total of 18 minutes and 42 seconds.

"I was always aware of where we were heading structurally,” says singer Jon Anderson. “I was listening to a lot of classical music while touring; I liked Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 – it’s got a very wild first movement, a gentle second, and the third movement is very majestic. I thought the band could get into performing with that sort of musical positioning.”

Another influence on his thinking was the recently-released Sonic Seasonings, a double album by electronic music pioneer Wendy Carlos consisting of four side-long long suites, brimming with evocative Moog-created ambient environments. Anderson discussed with Yes engineer Eddy Offord how they might come up with something similar.

“I wanted to create this sense of energy, a forcefield, before the band started, then have the group climb out of it with a wild and crazy solo section, raving away as though we didn’t know where we were going,” the singer says. "You’d get to a certain point, stop dead, and a very straight choral thing would come in; then the band would carry on again."

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

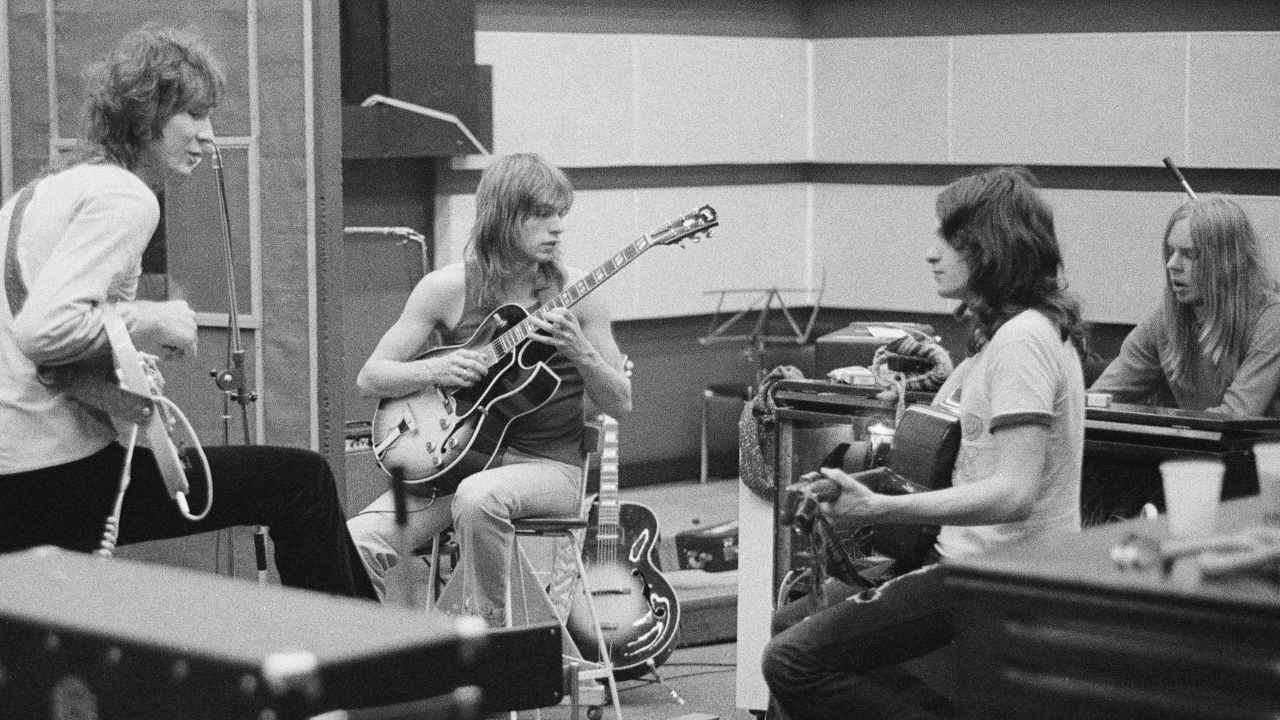

It wasn’t just classical music the band were drawing on. Howe's octave-jumping solo work in the whirlwind sweep of The Solid Time of Change owes little to conventional rock and nods more toward a jazzy sensibility. “I wouldn’t say we were influenced by the Mahavishnu Orchestra directly,” the guitarist says. “But we were all full of admiration and respect for them. It was that way-out jazz side of things we were drawing on."

Close To The Edge became a repository for a variety of half-formed ideas that, in some cases, had been around for a while. “You tend to have plenty of ideas and sketches which don’t necessarily have a home, so you pitch them in," says Howe. "Jon and I worked like that all the time. One of my songs had the line, 'Close to the edge, down by a river', which actually referred to where I was living at the time, next to the Thames.”

When Anderson heard the phrase, the symbolism of the river immediately connected to metaphors within Herman Hesse novel Siddhartha, which he’d been reading at the time. “The river leads you to the ocean; all paths lead you to the divine. So the idea was that, as human beings, we’re close to the edge of realisation," he explains.

Other early Howe songs were thrown into the mix. In Total Mass Retain, a descending guitar line had previously existed as part of Black Leather Gloves in his pre-Yes outfit Bodast. In the following movement, I Get Up I Get Down, his 'In her white lace' melody was originally a humble love song.

Anderson countered it with a melody of his own. “When I started singing 'Two million people barely satisfied,' I had in my in head what was happening around the world – starvation in African countries. So many people lived so well while so many people didn’t. ‘I get high and low on the whole concept of life. I get up, I get down.’ It worked out that Steve and Chris sang that, while I sang my melody over the same chords. It was magical – it just happened.”

I Get Up I Get Down has its majestic feel thanks to the appearance of the church organ recorded in London’s St.Giles-without-Cripplegate. There were huge challenges in getting it right, says Wakeman.

“The technology couldn’t do what I wanted it to do. So it was a matter of recording the organ separately, then ‘floating’ it into the track from quarter-inch tape. A long and very fiddly process, but absolutely worth it.”

Wakeman's Moog solo at this section provides a dazzling bridge into the track's finale, The Seasons Of Man. Driven by whip-crack drumming, crunching bass surges, diaphanous three-part harmonies, chiming guitar and piano, replete with ghostly Mellotron, it's Yes at their most cinematic.

Despite the passage of time, Howe remains impressed with the outcome. "To this day I think how Jon sang it originally in the studio in G minor is just amazing.”

It's something that Anderson cherishes as well. "That big end section is that place where it’s like we’d climbed the mountain,” he says. You get there and you sit back and take in the view. My head was spinning every time I listened to it or sang it.”

Close To The Edge was a transformative moment for Yes, the point when they finally fulfilled their ambition to produce a long-form piece of exceptional quality. They’d go on to write longer songs – but none would have the impact it did.

Sid's feature articles and reviews have appeared in numerous publications including Prog, Classic Rock, Record Collector, Q, Mojo and Uncut. A full-time freelance writer with hundreds of sleevenotes and essays for both indie and major record labels to his credit, his book, In The Court Of King Crimson, an acclaimed biography of King Crimson, was substantially revised and expanded in 2019 to coincide with the band’s 50th Anniversary. Alongside appearances on radio and TV, he has lectured on jazz and progressive music in the UK and Europe.

A resident of Whitley Bay in north-east England, he spends far too much time posting photographs of LPs he's listening to on Twitter and Facebook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.