“There were arguments. But they weren’t personal – they were musical. They helped make it what it is”: How Yes defined themselves with Fragile, before success went to their heads

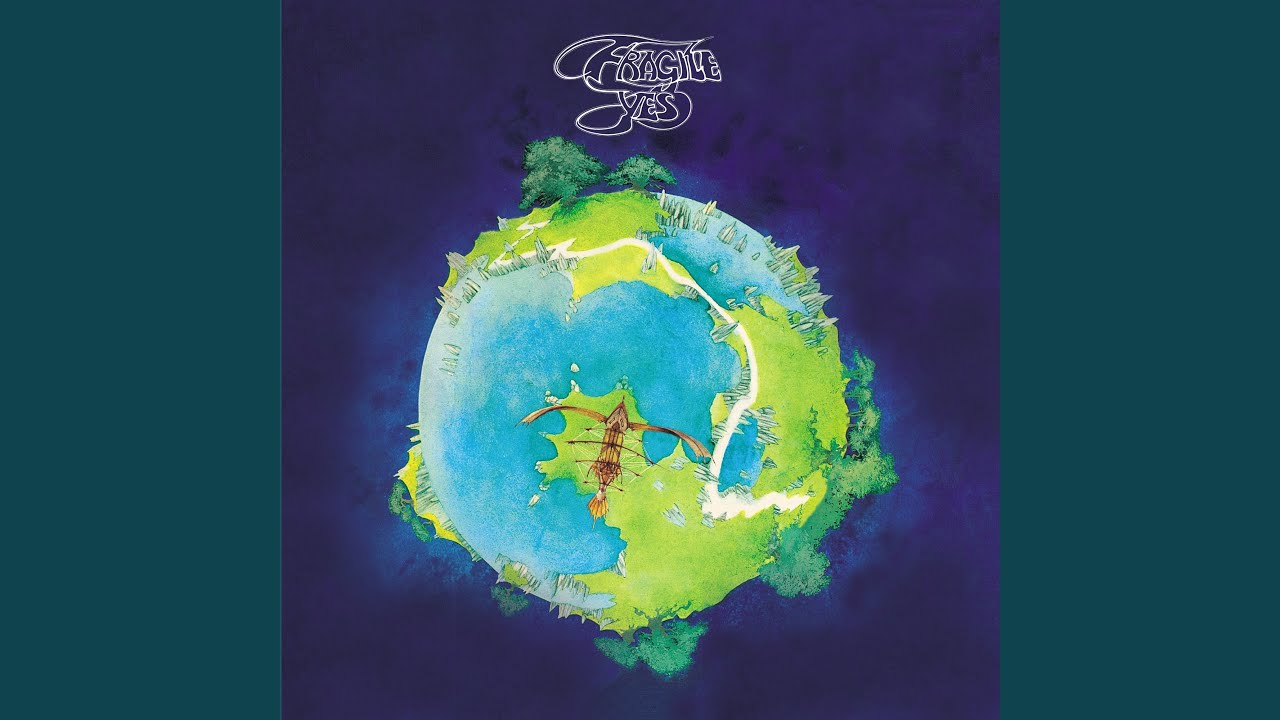

The arrival of Rick Wakeman, the freedom to be adventurous and the discovery of Roger Dean led to the creation of a prog landmark in 1971

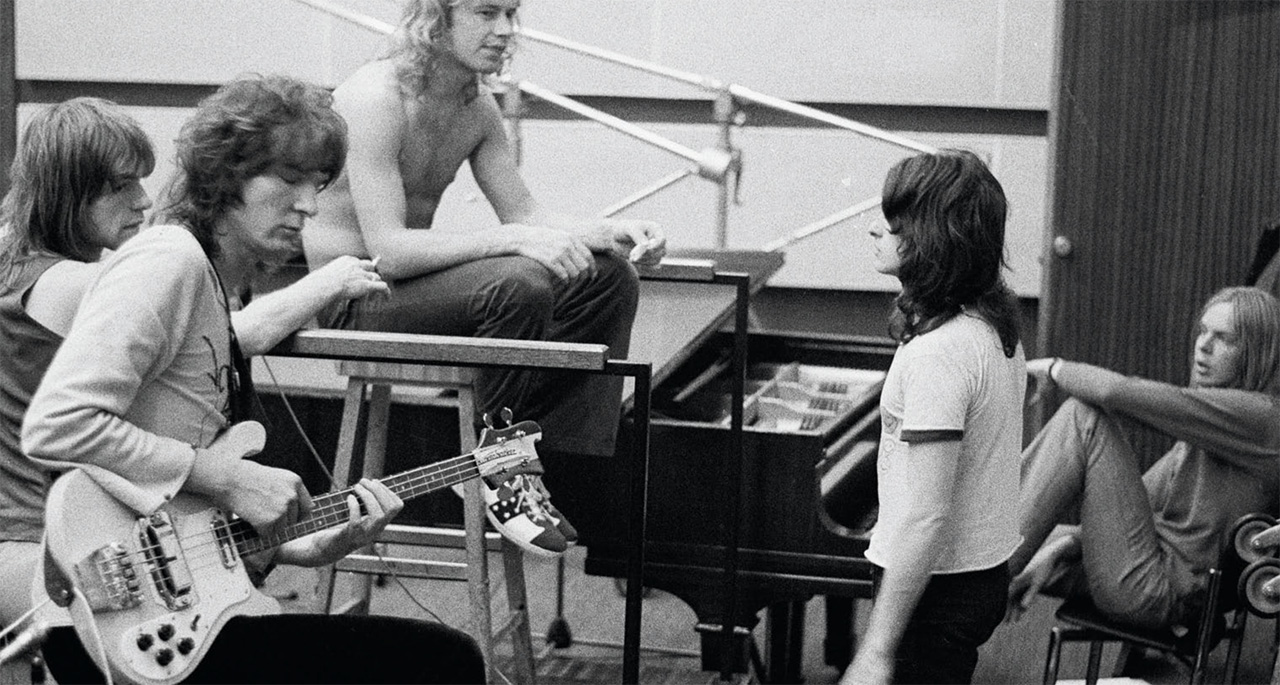

It’s the album on which Yes turned up the heat, with the assistance of new member Rick Wakeman and the discovery of Roger Dean – but it didn’t come without their trademark intra-band friction. In 2011 Prog discussed 1971’s Fragile with Jon Anderson, Steve Howe, the late Chris Squire, Bill Bruford and Wakeman.

“Golly jeepers!” exclaims Jon Anderson upon being reminded it’s the 40th anniversary of the release of the fourth Yes album, Fragile. “That’s freaking my freak! I’m always amazed by how beautiful it sounds.”

Steve Howe recalls: “The Yes Album was pretty good, but when Fragile came out it was like we’d turned up the heat.”

“I don’t really have favourites,” muses Chris Squire, “but that one does resound. It allowed us to unlock the door to success.”

Rick Wakeman concurs: “It was an unbelievably exciting launch-pad for us. As musicians we thought, ‘Oh boy, we’ve got something here!’”

Bill Bruford reckons: “Viewed from today’s perspective of over-computerised, cosmetically enhanced, processed auto-pop, Fragile sounds like the real thing. And, strangely, people like the real thing.”

Released in November 1971 – the year prog exploded with the likes of Pink Floyd, Genesis, ELP and Caravan recording then-pioneering, now-landmark albums – Fragile saw Yes swiftly yet ambitiously following up February’s The Yes Album, which had been Howe’s debut.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We were beginning to experience pressure, no doubt about that,” Squire recalls. “We realised we were really in the game.” They were gathering acclaim and sales in both the UK and the US. “We were getting used to what was expected of us if we wanted to carry on building this band.”

Key to this building was the addition of Wakeman, replacing the synth-phobic Tony Kaye. Having played with Strawbs and in sessions for Bowie, T. Rex and Elton John, Wakeman much sought-after. “He was very colourful,” remembers Howe. “He brought in more textures. There was plenty of interaction and genuine musical chemistry. That Yes was the quintessential 70s line-up.”

“It was a wonderful time,” adds Anderson. “There was so much harmony within the band. We were getting successful, but it hadn’t gone to our heads too much. We were all committed to creating adventurous music, and we were given the freedom to do that.”

There’s evidence in the playful exuberance of Roundabout (edited for a US hit single – “of course we hated that,” says Anderson); in the genuinely gutsy riffing and blissed-out dreamscape mid-section of South Side Of The Sky; the catchy yet complex and slightly ostentatious rhythms of Long Distance Runaround; and the juxtapositions of proto-thrash rock and choirboy innocence that constitute the epic Heart Of The Sunrise.

“I was interested in structure,” Anderson says. “How you get from one idea to the next, then the next.” These four lengthy yet precise labyrinths are the shapely body of an astonishing, elevated album, topped off by five brief(er) solo pieces, hung like jewellery on the frame. Some say they break up the flow; others that they make Fragile elegant, euphoric and enduringly surprising to this day. Even the band members maintain differing positions.

Anderson’s memory is that Howe (after impressing the band with Clap – unfortunately mistitled The Clap – on The Yes Album) and Wakeman had talked of doing pieces.“I went downstairs in Advision, where ELP were recording but had the weekend off, and did We Have Heaven,” the singer recalls.” I was so excited I told Chris he had to do a piece. I was always thinking about how it’d be onstage.”

I’m very proud of the bits I threw in. Yet history records that I didn’t do anything

RIck Wakeman

Yet Wakeman credits Bruford with the idea. “He was brilliant at reining people in.”

For Howe, it was the logical next step. “They said, ‘Have you got anything else?’ And I had. Everybody had their moment. It was a very exploratory album.”

Squire is rather more pragmatic: “We were really up against it time-wise. We didn’t have any more group material, so someone said, ‘Let’s all quickly come up with an individual thing.’ Not that we were looking for filler...” The multi-tracked reprise of We Have Heaven remains as vivid a ‘hidden’ coda as that of Abbey Road.

Everybody agrees that the record company were very relaxed, letting the band stretch their musical ideals. And they all say that the contribution of engineer-turned-produer Eddy Offord was invaluable. “Oh my God, he did a great job,” says Anderson.

“He stepped up his game,” says Howe, citing the backwards piano fade-into- harmonics that begins the album.

“I was sleeping in the studio sometimes,” Anderson continues. “I was so thankful that we were able to go in there. I was like an explosion of energy and dreams and ideas. The writing, the creativity, the potential – Fragile solidified the idea of the band. We’d only been together three years, and you don’t know how long it’ll keep going. So you keep going.”

Wakeman, who had his own record deal, suffered contractual hassles which limited his choice of solo track Cans And Brahms and denied him co-writer credits. “Someone said, ‘Don’t worry, we’ll correct it as soon as we can,’ but of course they never did. It’s not so much the money as the fact that I’m very proud of the bits I threw into Heart Of The Sunrise and others, like the piano piece that links South Side Of The Sky. Yet history records that I didn’t do anything.

We knew Rick was going to work; it was a formality

Steve Howe

“The way Yes worked, it would end up seamless. We’d all bring along bits of the jigsaw, then between us we’d slot the pieces in. If a piece didn’t work, it would get slung away. Gluing it together became my job in a strange way. All these little bits would be in different keys so we’d need chords over it. Bill said:, ‘That’s Rick’s job. He went to the Royal College Of Music. We didn’t. He studied orchestration. We didn’t.’

“I was actually thrilled. I’d be left for a few hours to come up with as many different progressions as possible. It was nice – that was one area where there were no arguments.”

Howe agrees: “We auditioned Rick in the studios in Mayfair. We knew he was going to work; it was a formality. I think they’d known I was going to work when I’d walked in, but with Rick it was obvious. Just like I enjoy all the different ways you can play guitar, he enjoyed musical knowledge. He’d say, ‘Oh, that’s called a recapitulation’. We didn’t know! He was an immense help to our construction work; everyone became very creative.”

While views differ as to whether the sessions were fuelled by heat or harmony, the latter seems to edge the vote. Anderson maintains that everything was dandy until business concerns stuck their oar in. Squire emphasises how hectic the period was, with Fragile recorded in bursts between US tours.

Wakeman says: “There were arguments. But they weren’t personal– they were musical. At the end of the day they helped to make it what it is.”

“The ‘love and peace’ movement was still present in a lot of hopefulness and optimism,” says Howe. “There was a burst of… not knowing, but sensing that we could go off on our limb and make a name for ourselves as this thing called Yes. There was a lot of good feeling. We were in each other’s pockets, writing, on the road, jumping in swimming pools together; a long way from where we all are today. It’s not altogether a bad thing that we’ve changed, but just how much we were doing together then is evident by how quickly Close To The Edge followed on its heels.”

King Crimson and the Mahavishnu Orchestra had been waking us up. You’d think you were good, then you’d go: ‘We have to be ridiculously good!’

Jon Anderson

Wakeman remained observant: “We rehearsed in Shepherds Market, Mayfair, above a, shall we say, place of ill repute. I was initially bemused by the number of ladies in fur coats wandering about at the height of summer. The crew disappeared every now and again.”

Meanwhile Anderson remained hungry: “At that time I was listening to Zappa and lots of different musicians. The world music scene then was very closed and I used to go and collect records from Indonesia, Africa, Russia. 1971 was lively, yes, but already King Crimson and the Mahavishnu Orchestra had been around, waking us all up. You’d think you were really good, and then you’d see somebody else and go: ‘We have to be ridiculously good!’”

“The first time I saw Yes, it was unlike any other rock band I’d ever seen,” Wakeman recalls. “You had a drummer who, technically, was so far ahead. Most lead guitarists had masses of Marshall stacks, and there was Steve with a twin reverb on the floor. Most bass players would go as low as you could; Chris had full treble on. And then of course most singers were six-foot-three with long straggly hair. On comes this diminutive chap with the most amazing alto voice I’ve ever heard.”

Another debutant on Fragile was Roger Dean, whose sleeve art and iconic logo initiated a Yes tradition and added to the music’s mystique and otherness. “Steve found him,” says Wakeman. “He was our George Martin, giving us another element.” Squire reckons it was “a happy accident” and Dean was randomly brought to the band by the label.

Anderson: “I wanted him to visualise what the music looks like. I said, ‘Think porcelain. Everything here – the band, the emotion, the success – could fall apart any minute; it’s fragile’. He came back with that beautiful world and I said, ‘Perfect!’”

“You listen to Fragile, and we’re each bringing something to the party,” Howe says. “And playing some funny stuff! That’s what people liked: that was our duty.”

“We were opening a door that not many people had tried to go through”, adds Anderson. “It’s a very daunting place to go, but Yes was all about a fusion of different energies, and we were given this amazing chance to do what I believe were great things.I don’t think of it as prog rock. The more we progressed, the less it became rock.”

“If ‘progressive’ is breaking the rules”, says Wakeman, “that’s what we were doing. Whatever’s in your head at the time, whatever you feel, that’s what you should do.”

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.