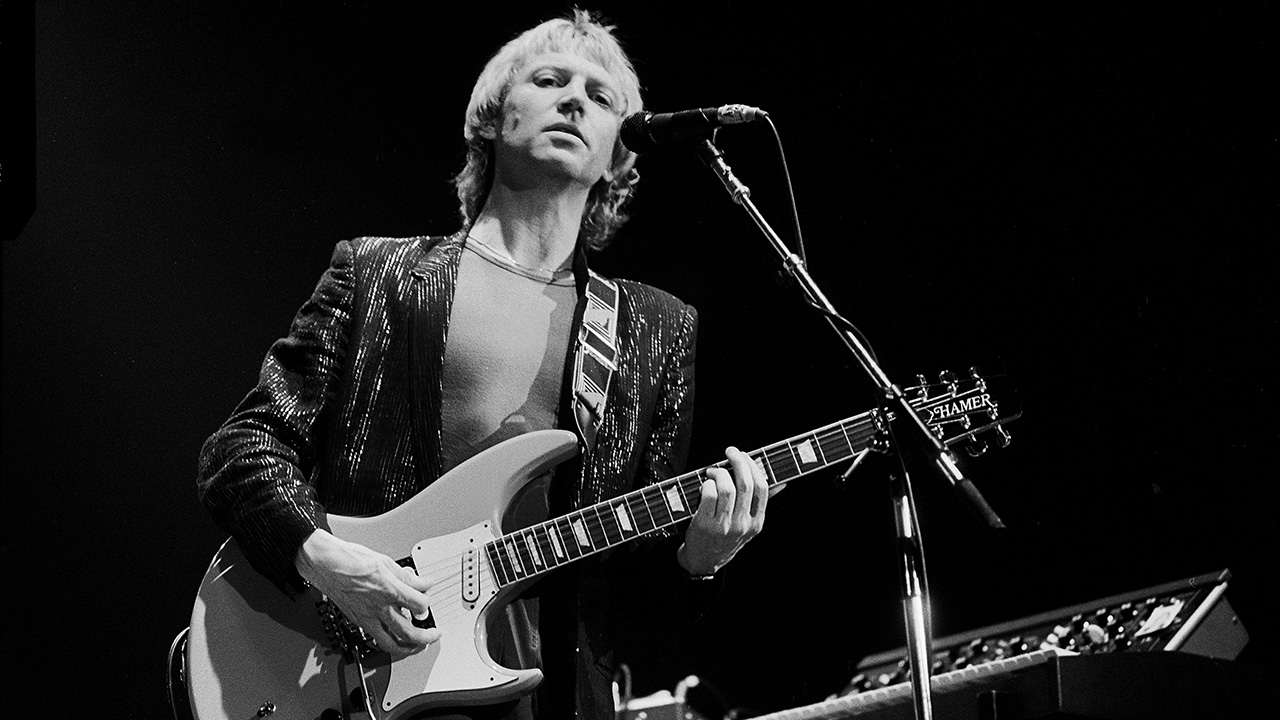

“It’s ludicrous a song like that would go on an album at the height of our fame, but it got the most notice because it was so bizarre”: The Police’s Andy Summers on success, psychedelia and working with difficult people

The multi-faceted guitarist looks back on a career including stints with Robert Fripp, John Cale, Kevin Ayers and others

Andy Summers worked across a wide range of genres before The Police became huge. He played with Zoot Money, Soft Machine and The Animals, and even jammed with Jimi Hendrix. In the 80s he collaborated with Robert Fripp, and in 2015 continued his experimental creations with Metal Dog. That year he gave Prog the benefit of his insight and experience.

Andy Summers was there during the British R&B boom of the mid 60s, the acid rock scene of the late 60s and the birth of prog in the early 70s. He went from playing trad jazz and blues to dropping LSD, featuring in Jenny Fabian’s fabled carnal misadventure Groupie and jamming with Jimi Hendrix (“It was incredible; surrealistic,” he recalled). He joined Soft Machine and The Animals (Eric Burdon’s house was a riot of “girls, bikers and dope dealers”) before heading off to study music at California State University, Northridge.

Back in London, he recorded and toured with Kevin Coyne, Kevin Ayers and Jon Lord, and was even mooted to be Mick Taylor’s replacement in The Rolling Stones. He took part in a performance, with the Newcastle Symphony Orchestra, of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells, and was invited by Mike Howlett of Gong to join his short-lived new outfit, Strontium 90, alongside a bassist called Gordon Sumner, alias Sting, and an American drummer called Stewart Copeland who had been in prog outfit Curved Air. Then they formed The Police and became the biggest band on Earth.

Of course, it wasn’t quite that simple. The band’s ascent was fast, but there were bumps. For a start, the so-called Bleach Boys were widely loathed by critics and punks alike for being old, and for their supposed Machiavellian dilettantism, dyeing their hair and doing a TV ad for Wrigley’s chewing gum.

But it was their (gasp, shudder) prog past that caused most eyebrows to be raised. Apart from Sting’s stint with jazz fusioneers Last Exit, Summers’ tenure with the likes of the Softs and Copeland’s stint with Curved Air, they had a manager, Copeland’s brother Miles, who had looked after Wishbone Ash and Renaissance. The Police were so prog they even spent the end of 1977, not gobbing and pogoing down the Roxy, but collaborating with German avant-garde composer Eberhard Schoener.

Indeed, so different were The Police to your average rock power trio – especially Summers’ jazzy chords and reggae rhythms, with their focus on dub space – that they caught the ear of no lesser personages than Rush. “His tone and style were just absolutely perfect – he left space around everything,” Alex Lifeson said. “And he can handle anything from beautiful acoustic playing to jazz to hybrid kinds of stuff.”

Summers’ guitar playing was one of The Police’s hallmarks, and he has been lavishly rewarded for it, earning a clutch of Grammys for his instrumental prowess. But notwithstanding their 75 million record sales, they’re not the only thing on his CV. There have been team-ups with Robert Fripp – I Advance Masked (1982) and Bewitched (1984) – as well as a further rock band foray, with Circa Zero, film scores, and numerous solo albums, up to and including 2015’s Metal Dog.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He’s a polymath: a painter, a photographer, a writer (his 2006 autobiography One Train Later was voted music book of the year by one publication) and filmmaker (the documentary Can’t Stand Losing You: Surviving The Police was released in 2012). He’s also credited as the peacemaker in The Police, although he disputes this role.

“It was more like three clashing egos,” he has argued. “It was a three-way circus and I certainly didn’t feel like the referee.” He had his own dark nights of the soul as he tried to get a grip on success. As he declares at one point in Surviving The Police: “I’m a rock’n’roll asshole, an emaciated millionaire prick – and fuck everything.”

I made a couple of records with Robert Fripp which pushed the envelope and were very influential

Metal Dog is quite an experimental album – harsh and metallic, even – for a 72-year-old to make. This is a compliment. It sounds like the work of a much younger (post-)rocker.

Let me qualify some of that. I don’t think it’s unusually harsh and metallic. I think there are some very lyrical, soft moments on there. Some of the tracks are quite exotic, influenced by Balinese music. It’s a mix of things. But I don’t know what age has got to do with it at all.

It doesn’t sound like a bunch of amiable blues jams…

Well, I haven’t become jaded; I’m still trying to be on the cutting edge, if that’s the appropriate term. I’m always moving forward. I’ve done a lot of out-there, edgy stuff. Not, like you say, some old blues rock, which I have zero interest in.

So this one isn’t a radical departure?

No, I started doing this stuff a long time ago - I made a couple of records with Robert Fripp in the 80s which pushed the envelope and were very influential on a lot of people. So no, I don’t think this is a radical departure at all.

Would fans of De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da be freaked out by it?

No, I think it’s a very appealing record. If they’re freaked out by it, good. Time to get freaked out!

Are you an experimental musician who just happens to have been in one of the biggest rock bands of the last 40 years?

[Laughs] I would say, yeah. I grew up playing jazz as a kid; that was my thing – to be like an American jazz guitar player. I wanted to learn the harmonic stuff, which I got by the time I was 16. Later on in London I was in rhythm and blues bands. I was listening to a lot of world music, Indian music and Miles Davis, Coltrane. And then I got into Oliver Messiaen and John Cage: so-called 20th century avant-garde music.

Was Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band your first band?

Yes. We were an R&B band. Our first show was basically [1963 album] James Brown Live At The Apollo in its entirety! We were doing American R&B, which was a great training ground, and we were very successful, very popular.

Did you mix with the other R&B kids – The Who, Animals, Stones, Yardbirds, Manfred Mann…?

Oh yeah, we were all friends. Everyone who is legendary now was all hanging out together in clubs. There was Eric Clapton, John Mayall, Fleetwood Mac, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, Albert Lee, Ronnie Wood was around…

I really liked Soft Machine – it was where my head was at. I particularly enjoyed playing with Robert Wyatt

How good a guitarist were you?

Very good! Of course, I was completely obsessed with it. I was practising all the time, trying to learn all the [jazz guitarist] Wes Montgomery stuff.

Didn’t you drop your first tab of LSD with Zoot’s band Dantalian’s Chariot?

It might have been with The Big Roll Band, thereby helping to cause the breakup of the band. One thing led to another.

Did you feel more at home playing acid rock than R&B?

I did. At the time, I was listening to very exotic music, trying to play scales. Everyone was getting into the blues and I was trying to play like Ravi Shankar. Obviously I was around a lot of guys wanting to be Eric Clapton, but I wanted to go in a different direction.

In your autobiography you describe your guitar sound as “high cloudy chords coloured by echo and delay”…

I don’t remember plugging in lots of boxes in Dantalian’s Chariot. Even fuzzboxes, if they were around, were an absolute novelty. Guitarists didn’t have a whole array of pedals.

When you were invited to play with, variously, Kevin Coyne, Kevin Ayers and Soft Machine, did they hire you because of a reputation for a certain style?

I don’t know if I can put it in those terms. When I met Robert Wyatt the first time, we all went on this fantastic trip to Paris. It was like every psychedelic band in London got on the train. I really liked Soft Machine – it was where my head was at. I particularly enjoyed playing with Robert. Kevin [Ayers] was difficult…

You spent three months in the States with Soft Machine. Did you consider yourself to be prog?

Not particularly.

You were doing prog things: working with Ayers and Wyatt, performing Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells…

I guess you could call that prog.

With you on guitar?

Well, I wasn’t playing trumpet! Mike was dropping out of the scene and I was a notable guitarist around Virgin so they asked me to do it. It was significant because the band in the intermission was Last Exit, featuring Sting playing bass, then still living in Newcastle. A weird bit of synchronicity, if you like.

Another prog-esque moment came in 1977 when you were invited by Mike Howlett of Gong to join his new band Strontium 90…

‘Prog-esque’ – that’s a good one! Mike put together this band, as history knows, with me and Stewart and Sting, and himself, so we had two bass players. But we weren’t playing prog, we were playing punk, pretty much.

I never sat around listening to reggae; none of us did

There was quite a lot of punk/prog crossover music at the time - bands like XTC, Magazine, Wire and The Stranglers could have gone either way, it seemed…

That was the big joke – half of these bands swearing they were punk and overthrowing the establishment were all prog fans! I know Captain Sensible of The Damned totally liked Egg and Hatfield & The North.

Jon Anderson described The Police as the last great prog band…

I don’t know how he came up with that. It was a genre unto itself, but it certainly wasn’t prog.

Didn’t you have prog tendencies?

Define prog!

Music that strays from three-minute pop song conventions and stretches out instrumentally?

The Police could improvise forever, but we didn’t do the very elaborate, baroque arrangements that Genesis or Yes did. So I don’t think we were prog. Ultimately we were new wave, fresh, stripped-down pop music. The symphonic quality that the most classic of prog bands had, we didn’t have, but we had many influences, which is one of the reasons the band is the way it is – because of the chemistry between the individuals.

The guitar sound on Bring On The Night (from 1979’s Reggatta De Blanc) has been described as Fripp-ish… And Mother (from 1983’s Synchronicity) was proggy, wasn’t it?

I don’t think Bring On The Night was Fripp’s style at all. Mother, which I wrote, was in 7/4 and it was ludicrous that a song like that would go on an album at the height of our fame, but it was the one that got the most notice because it was so bizarre…

Did you feel musically superior to your peers?

That sounds big-headed – but we did become the biggest band in the world and no one could compete with us! There were other bands I liked: Talking Heads, Television – the American ones. U2 later when they turned up had promise and fulfilled it. Most of the hardcore punk bands didn’t come to anything and disappeared.

Confirmation of the difficulty of pigeonholing The Police came in 1978 when you supported jazz-psych West Coast legends Spirit and leftfield punks Alternative TV at London’s Rainbow…

I remember that gig because it was a big jump up for us, and significant, to be on the bill with this famous band from California.

ATV, like The Police, were reggae-influenced and featured Mark P from seminal punk ‘zine Sniffin’ Glue…

Mark Perry was very hardcore punk. We had a bit of a scene with him – he thought we were traitors who betrayed it all! The reggae thing has been totally overplayed in the case of The Police. I never sat around listening to reggae; none of us did. But the punks accepted reggae as cool, and dub. I wasn’t heavily into Jamaican culture, but the basslines and rhythm on a couple of songs were useful elements to add to what we were doing.

We got through the whole show in 12 minutes because we played so fast!

Did Miles Copeland, your manager, have a “eureka!” moment when he heard Roxanne?

Yeah, we were ashamed to play it to him because it was kind of a ballad, and certainly didn’t fit in with the punk scene. But when he heard it he was like, “Fuck! This is great!” We were all a bit shocked because we thought he’d hate it.

You went in the studio around the same time with John Cale, didn’t you?

We had one session where he turned up completely drunk. He didn’t know what the fuck he was doing. We were all there ready to go, and Cale just destroyed us – it was a waste of bloody time. The only time he made a suggestion was when I played some Led Zeppelin riff. He said, “That’s what you’ve got to do!” Right, okay, let’s get out of here…

You played your first gig proper the same day Elvis Presley died, at Rebecca’s in Birmingham, on August 18, 1977?. That was a bit “out with the old, in with the new,” wasn’t it?

Yes. Unbelievably, we got through the whole show in 12 minutes because we played so fast! The rest of the hour we started playing the songs again, only extending the improvisation.

Did you get a lot of punks gobbing at you?

At the beginning people didn’t know what to make of us, Stewart being in Curved Air and all that… Amongst the hardcore, The Police were jumping aboard the punk bandwagon. To an extent that was true.

It was cool at first, and then it just sort of broke. There was complete chaos in the London clubs. We played at the Nashville and people were trying to climb in through the window of the toilets; whatever it took to get in and see the band.

Was the fact that you were strategic, using punk as your launchpad, really such a bad thing?

Once we started to smell it, we wanted it, like anybody would. We were selling millions of records. We were three pretty smart guys who would sit together, like a company. And we would strategise and think about how we could be different from other people. But basically it all came from the music. Yeah, we looked good, the music was very appealing and aggressive enough, but we thought about what we were doing. We weren’t just led by a manager and drugging out.

Despite the fact that two of you were in early-70s bands and you had your roots in the 60s, The Police sounded, to Prog’s ears, largely un-influenced by the past…

I actually thought The Police were like the last great 60s band.

The pressure on us was phenomenal. We were saving the entire music industry, on our own!

Do you agree your biggest artistic leap was between your debut Outlandos D’Amour (1978) and Reggatta De Blanc?

Possibly, yeah. The first album, we were trying to find our feet. It was made over a period of six months, on and off, whenever we could get a free three hours in the studio. By the time we got to Reggatta De Blanc, we were a very hot property and gigging non-stop, still in the first flush and very excited, so we made it in 10 days – all of our albums from that point got made in about a week.

Was it pleasing to hear something as strange as Walking On The Moon on daytime radio?

Yeah. We were absolutely shocked. It was like, “God, we might just be able to pull this off!” That was when we started getting all the media attention. Deservedly so – we were really good! And obviously it wasn’t a one-hit wonder – we kept coming up with the stuff. We weren’t falling apart from drug abuse or whatever. It was very exciting: Reggatta De Blanc going straight in at No 1, the US wanting us, touring Japan… It’s a technicolor blur. Later, when you’re No 1 in the world and playing stadiums, it gets different. You get, not jaded, but I think your brain changes.

You have to be mentally strong?

Yes. It’s very destructive. But we didn’t let either of the other two get big-headed. We grounded each other. [To an imaginary Sting] “Look, man, pick up your fuckin’ bass! Fucking rehearse!” or whatever. No one really lost the plot. It’s very easy to go off the rails.

Did you learn lessons from superstar musicians you’d seen or hung around with?

I think as we were up in the stratosphere I felt a certain sympathy for people who get lost in drugs and all that. The pressure on us was phenomenal. We were saving the entire music industry, on our own!

Did you think back to Hendrix, who you’d jammed with?

Yeah. Empathy with people who didn’t make it in the end. I just watched that film about Amy Winehouse – oh my god. She was so talented and got mixed up with the wrong people. Drugs and drink, what a bloody waste.

That never happened to The Police. You flew so high, but there was very little damage?

Not like that, no. You had three fairly strong blokes watching out for one another. We weren’t goody-goodies by any means – we were a rock band. We went through it all and there were some crazy times. But we didn’t go under, even though we were surrounded by people who wanted to give us drugs and everything… We were instrumentalists – each concert had to be better than the last one: fierce and full of invention. We fairly early on realised we could have gone either way, but if we’d have gone to the left [towards self-destructive behaviour] we’d only have lasted six months.

We were playing the music we wanted, to huge audiences, making millions of dollars. What wasn’t to like?

Was it weird to have outstripped, commercially, people you’d worked with and admired, even some of the biggest names in rock?

It is weird. All these bands like the Stones and Pink Floyd - we ended up being bigger than all of them.

Weird especially because you’d been mooted as Mick Taylor’s replacement in the Stones, hadn’t you?

That was just bullshit, really. I’d been playing in London and I was very good, I got lots of great write-ups in the music papers, and it was like, “He should be in the Stones.” Instead, I took a complete turn to the left and joined an unknown punk band with absolutely no future whatsoever! On paper, it was madness. I was getting a paid retainer by Elton John’s management, and I was playing with Kevin Ayers. But I walked away from it to become penniless with The Police.

Fast forward a decade… By all accounts recording Ghosts In The Machine (1981) had been tough, and your marriage crumbled around that time, but what was it like being the biggest band on the planet circa Every Breath You Take and the Synchronicity album?

It was phenomenal fun. We were playing the music we wanted, to huge audiences, making millions of dollars. What wasn’t to like? We weren’t miserable – it was amazing.

Considering how big you were, you could easily have become far worse human beings.

Yeah. We were… mildly debauched.

In the end, you lasted about the same time as The Beatles…

It’s probably enough for any band. There’s definitely a moment when you’re on creative fire and it’s probably in the early to mid-period. I don’t know if a band is meant to last 40-45 years.

Of all your awards and accolades – Grammys, Guitar Player magazine No 1 Pop Guitarist for five years – do you have any favourites?

It’s all great. I’m just glad people are still interested! I feel very grateful that I can still play as well as I do, that I can sit down and play Bach all day long or I can go in the studio and make records like Metal Dog.

Did you get any angry phone calls from Sting or Stewart after they saw the documentary?

No, they weren’t angry. In fact, Stewart was very complimentary about it. I heard from Sting’s manager and he liked it! There are a couple of tense moments in there - “Oh god, they’re not going to like this!” - but no one said anything.

Where you live in Santa Monica, what kind of reactions do you get?

People come up and say, “God, you were such an influence on me…” I get it a lot, whether I’m in Beijing, Tokyo or London. I get the occasional bore and I’m like, “Fucking hell, get me away from this guy!” The most irritating thing now is everyone wants an iPhone photograph.

That tension: you need it. It was an ongoing friendly fight that lasted seven years!

Still, at least you don’t have to deal with the more negative sort of attention, mainly from the media, that Sting always got, all that “priapic love god” lampooning..?

I had a bit of that in my time, and it’s really naff. I feel for him in that way. It’s dreadful.

What’s it like being in a band with someone who is the subject of universal derision?

It’s bullshit because if you know the person you find out they’re actually very different. But one of the things about the UK is, once you lift your head above the parapet, they shoot it off. That’s one of the reasons I left the UK - I couldn’t take it anymore. In the US you don’t have that paparazzi in-your-face thing. You sort of want it, but not all the time. I mean, poor Amy Winehouse, look what they did to her – they basically killed her.

Do you enjoy The Police’s mythic reputation for bust-ups and intra-band loathing?

It’s what you want, really. There’s a reason the band has the status it does. We were a great fuckin’ band, almost never equalled, with great songs, and a great vocalist with a very distinctive voice. And we all looked good. All the right elements were there. It’s sort of miraculous.

Does the combustible nature of your relationship get overplayed?

It does, but what would you expect? I think any rock band by definition has to have that sparky chemistry – all the great ones have it. That tension: you need it. It was an ongoing friendly fight that lasted seven years!

How about the idea of you as three warring factions locked in your own lonely corners…?

That is overplayed. It’s so irritating. I live here in LA, Stewart lives five minutes away, we talk every week, Sting’s been in touch… It’s not as though we ended up poisoned by one another and never spoke again.

Maybe people like the paradox of the pleasant melodists with the disharmonious relationship?

True, and that’s an interesting thing: great creative artists aren’t necessarily nice people. They’re all kind of arseholes. Beethoven, Picasso - you name ‘em, difficult people. It goes with the territory. But it finds its way into the music and is what gives it its strength.

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.