“The label didn’t want me to do it, but didn’t want to piss me off. We were both famous guitarists so I thought there’d be a lot of interest. I was right all along”: Andy Summers and Robert Fripp collaborated with remarkable ease

When the Police and King Crimson men got together, the result was two well-received albums and a stack of forgotten material – finally released – that they can’t believe wasn’t used in the 80s

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

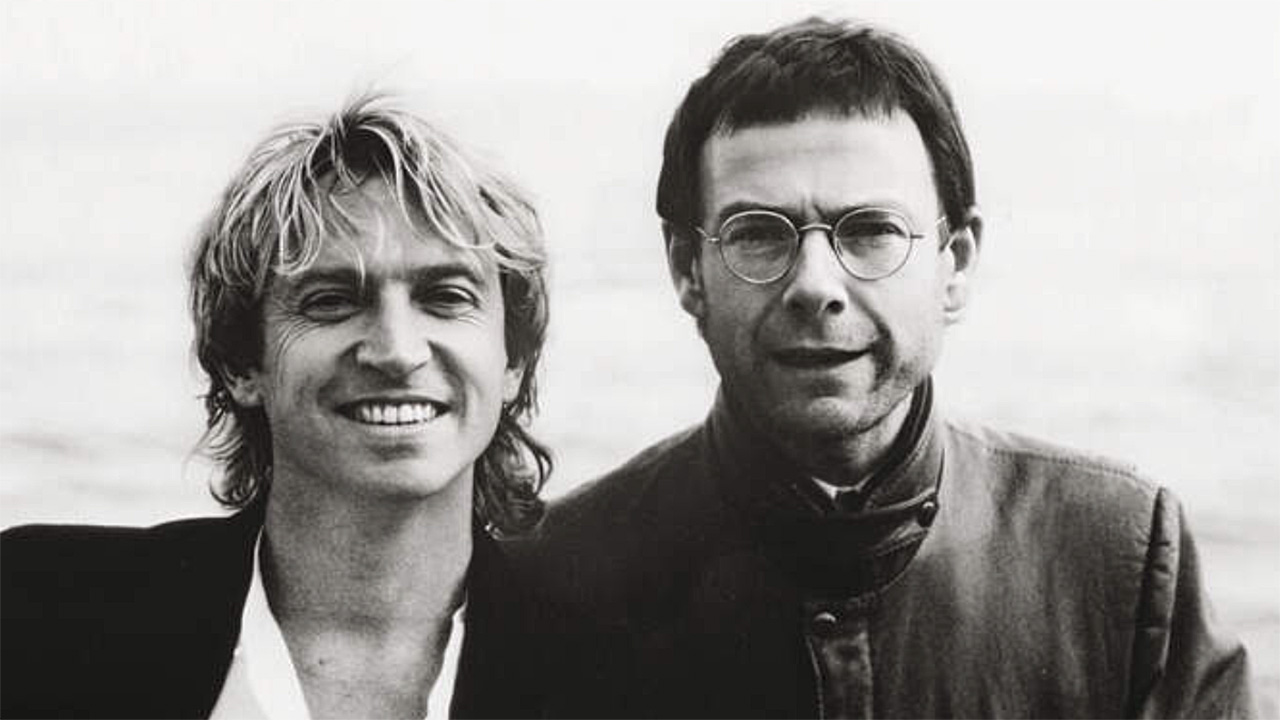

When Andy Summers teamed up with King Crimson’s Robert Fripp at the dawn of the 80s, it afforded The Police guitarist the chance to rediscover a musical mojo left wanting as a result of phenomenal mainstream success.

With these collaborative efforts now newly compiled, along with a mini album of lost recordings, Summers and Fripp look back on the sessions that would embrace avant-garde improvisation, state-of-the-art guitar technology and a bold attempt to fuse both the “out-there” and the “accessible.”

By October 1980, The Police were fast becoming the biggest band on the planet. Already hugely successful across Europe and the Southern Hemisphere, the trio’s major breakthrough in the States was triggered by new album Zenyatta Mondatta, housing infectious singles Don’t Stand So Close To Me and DeDoDoDo, DeDaDaDa.

Yet conquering the mainstream also brought a degree of frustration for Andy Summers. When their tour hit Munich, the guitarist sat down in his hotel room and wrote a letter to Robert Fripp. “I’d been in the band for a few years and I wanted to try something else, musically, just to prove that I existed outside of the framework of The Police as a musician,” Summers explains today. “I’d really loved the Roches album [1979’s The Roches, produced by Fripp], especially Robert’s guitar playing on it, so it occurred to me to get in touch.”

Fripp was then involved with The League Of Gentlemen. And while it proved a short-lived affair, his sights were set on something more ambitious: a new “first division” rock ensemble that would eventually lead to a fresh iteration of King Crimson. For the immediate future though, Summers’ suggestion of a two-way collaboration was attractive.

“I’d seen The Police at the Bottom Line in New York in ’77 or ’78, and liked them a lot,” Fripp recalls. “Andy was a phenomenal broad-based guitarist. And you’re not really going to appreciate his rhythm parts in The Police unless you work through substitute chords and voicings. There was a hidden sophistication in his playing.”

Summers and Fripp met up in New York City the following year, when their respective schedules finally eased. “We hung out for an afternoon and got on very well, two English blokes from Bournemouth,” says Summers. “And we decided that we’d try and do something together.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Having had their first hook-up, they repaired to Summers’ house in Putney to jam. By September 1981, they’d booked themselves into Arny’s Shack, a studio in Parkstone, Dorset.

It wasn’t the random collaboration it might have seemed. They had history. In their formative years of the mid-60s, Fripp had taken over from Summers – then embarking on a career in London with Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band – as teenage guitarist in the dance orchestra at Bournemouth’s Majestic Hotel. “My responsibility was to provide the popular music of the day,” says Fripp. “So the band would turn to me and say: ‘What twists have you got, Bob?’”

Fast forward to 1973. Having spent the past five years studying classical guitar and composition in California, Summers returned to London looking for a regular payday. “I was at the Speakeasy one night and bumped into Robert,” he says. “I told him I was trying to get back into it and he suggested I call [King Crimson drummer] Mike Giles, who I’d also grown up with. Mike was setting up a touring band for Neil Sedaka, and I ended up getting the gig. So Robert really helped me at that juncture.”

In their own small ways, both incidents served to cement their musical bond when it came to recording an album together in 1981. Arny’s Shack was run by Tony Arnold, another childhood friend. “It was all very amenable,” Summers says. “Robert and I had no idea what we were going to play – we just sat with our guitars and various bits of equipment, and started to discover what could be made between us.”

They complemented one another handsomely. Fripp would often hit on a fluid rhythmic pattern, toying with tempo and time signature, while Summers would extemporise over the top or between the lines. Solos would erupt and elide just as quickly. Melodies would appear and mutate. Ambient motifs gave way to rolling experimental figures.

Summers was just about to embark on a mammoth tour for The Police’s Ghost In The Machine, having completed the album two months earlier. Fripp was still fresh from the sessions for King Crimson comeback Discipline.

What made Summers and Fripp work is that Andy was more able to move to me than I was to him

Robert Fripp

“I’d always aimed to be a broadly based player, although I was nowhere near as successful at that as Andy,” he says. “But working within King Crimson, my musical focus became increasingly defined and specialised. So what made Summers and Fripp work is that Andy was more able to move to me than I was to him.”

“My biggest influence was jazz,” says Summers. “Growing up, I was listening to people like Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell and Jimmy Raney. And I played classical guitar for years, so I was very schooled in harmonics. Robert and I are very disparate players – he ain’t gonna play the blues with you. He’s really good at playing these sort of polyrhythmic lines; I’d never heard anybody else play quite like that. So I regarded his multi-rhythmic lines as the bones of the skeleton, and my function was to put on the flesh. We were figuring it all out as we went along.”

An added feature of what became I Advance Masked was the Roland guitar synthesiser, still relatively novel in 1981. Summers and Fripp used it sparingly, but tellingly, alongside minimal touches of bass and percussion. “I began with a Roland guitar analogue synth in 1980, towards the end of The League Of Gentlemen’s existence,” Fripp explains. “It was hot new technology, which of course Adrian Belew and myself used in 1981 Crimson.”

“I’d previously used the guitar synth on Don’t Stand So Close To Me,” adds Summers. “It allowed you to move into a whole other sphere. And I took the Police pedal board into the studio with Robert, so instead of having two straight electric guitars going into two Fender twin amps, we were able to bring more sonic colour to the situation.”

I had all my overdubs left to do in one day before I left; so I put my head down and did them all in one and a half hours

Robert Fripp

A second session for I Advance Masked took place in May 1982 at Island’s Basing Street studios in London. The end result, released on A&M that October, was little short of extraordinary, a marriage of styles deftly balanced between the out-there and the accessible. Still, expectations for an all-instrumental guitar album were modest.

“A&M, who The Police were selling trillions of records for, didn’t want me to do it at all,” reveals Summers. “But they didn’t want to piss me off, because I had too much power at that point. Robert and I were both famous guitar players in our respective groups, so I thought there’d be a lot of interest in it. Then it went into the Top 60 in the US Billboard charts, so I was right all along. It was a real sort of fuck-you to the record company.”

The advent of MTV required Summers and Fripp to deliver a video for the title track, selected as a single. Recalls Fripp: “Andy called me in Wimborne and said, ‘We’re gonna have to do a video. What should we do?’ And as a joke I said, ‘We need Asian dancing girls.’ I kept a straight face, even on the telephone. But Andy said, ‘That’s a great idea!’ The next thing I knew, he had set it all up.” The video is one of the more surreal curios in each man’s singular catalogue.

They revived their collaboration in the spring of 1984. Circumstances this time around, however, were less ideal. Summers was just back from an exhausting nine-month world tour with The Police. Fripp had spent a good chunk of that time rehearsing and recording King Crimson’s Three Of A Perfect Pair. He had only a little time to spend with Summers before leaving for Crimson dates in the States and Japan.

I went into retreat after another three years of Crimson, hoping never to return to the music industry

Robert Fripp

“I think we should have delayed recording,” he says today. “We only had two weeks to record, so it was straight in. I had all my overdubs left to do in one day before I left; so I put my head down and did them all in one and a half hours. I came into the control room after one particularly burning solo and Andy said, ‘Vic Garbarini [music journalist] told me you could play like that, but I didn’t believe him!’ Then I had to go off on tour. Andy finished it as best he could. I think most or all of the second side is actually Andy doing solo looping.”

The resulting Bewitched was issued in September 1984. “I don’t know if we should have made the second album,” Summers admits. “I just don’t think we had enough tracks, and Robert didn’t have the time to stay all the way through. So we didn’t get all ‘out-there’ with it.”

Such self-critique feels justified in parts. At least half of Bewitched is more rock-orientated than its predecessor, while the occasional presence of session players robs it of I Advance Masked’s locked intimacy. But the album nevertheless boasts some inspired moments. The radiant title track, for instance; Forgotten Steps’ eerie beauty; and the silvery 7/4 chime of Maquillage.

Post-Bewitched, Summers and Fripp lost touch. “Our lives just shot off in different directions,” says the King Crimson man. “I went into retreat at the end of ’84, after another three years of Crimson, hoping never to return to the music industry. I came out of that to two primary changes in my life. One was the beginning of Guitar Craft [a series of Fripp-led classes], which is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. The other big shift was meeting little Toyah Willcox. She stole my heart. I proposed to her a week after our first date.”

What’s slightly shocking is these other tracks didn’t go on the original albums

Andy Summers

There would be no further Summers and Fripp collaborations. More than 40 years on, though, both I Advance Masked and Bewitched have been remastered as part of The Complete Recordings 1981-1984, bolstered by a third disc of previously unreleased pieces. Mixed and assembled by engineer/producer David Singleton, co-founder of Fripp’s DGM label, Mother Hold The Candle Steady is essentially a ‘lost’ album of wonderfully transgressive gems, featuring titles like Turkish Kitchen, Entropy Pulse and Ninja Acid Dance.

The tapes were only discovered when Summers began searching for the original album masters – in preparation for the reissue – in a Los Angeles vault. “I’d completely forgotten about them,” he says. “What’s slightly shocking to me now is these other tracks didn’t go on the original albums. It’s kind of astonishing, because they’re really good.”

An extra treat is fly-on-the-wall audio documentary Can We Record Tony? which is sourced from Fripp’s archive cassettes and offers an insight into the informal nature of the sessions, improvising freely and chatting leisurely between takes.

“Listening to the new reissue, the one I keep returning to is I Advance Masked,” says Fripp. “I love it. It’s stunning. And crucially, it still sounds fresh today. That album escapes the hold of time.”

“Sometimes the stronger things come out of the most unlikely pairings,” concludes Summers. “I think that was true of us. There’s a whole atmosphere to that first record in particular that doesn’t sound like anybody else. I thought it was almost revolutionary at the time. We created our own little mini world.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.