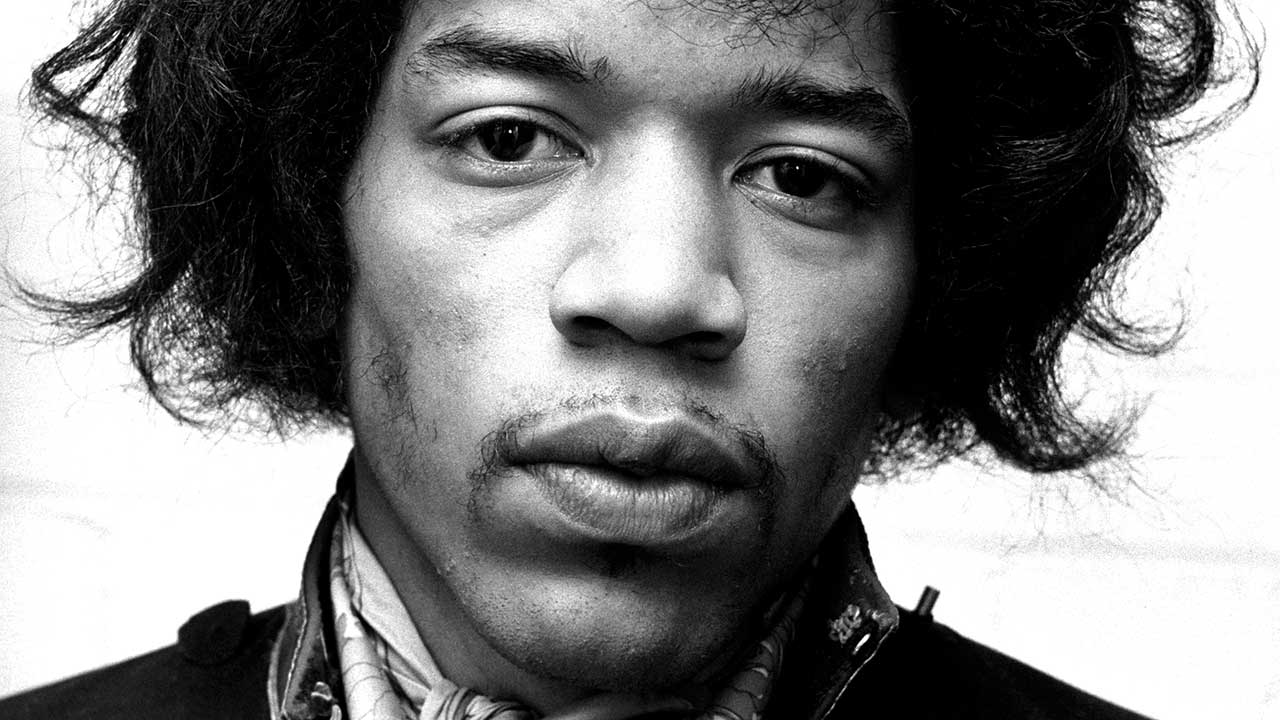

Jimi Hendrix: the life and times of a genius

Classic Rock talks to Jimi Hendrix's friends, admirers and other musicians about his life and importance

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The face of popular music was set to change forever when, on November 27, 1942 in Seattle Washington, James Marshall Hendrix was born. When his father bought him his first acoustic guitar when he was 15, events were set in motion.

After a stint in the army – wherein he formed a band with future Band Of Gypsys man Billy Cox – Jimi Hendrix was honourably discharged and free to pursue his musical ambitions.

Between 1962 and 1965, the guitarist began to stamp his artistic mark, playing sessions and gigs for the likes of Little Richard, Ike & Tina Turner and the Isley Brothers. By 1965, Hendrix found himself in New York City playing with Richard and Curtis Knight & The Squires. In July of that year, he would meet with The Animals’ Chas Chandler, and it would set the course of Jimi’s short, sharp rise to stardom and rock’n’roll immortality.

We asked friends and admirers of Hendrix to recall their memories of the great man and to pay tribute to his sparkling genius.

David Crosby: One of the reasons Jimi’s still such an important figure is because he was so complex. This was a guy who’d been in the 101st Airborne Division. You have to remember he wasn’t just some one-dimensional being. He was somebody who’d been quite aways in his life and he had real depth to him. Which is something you can hear if you listen to the songs – he wasn’t just a good guitar player. He was actually a brilliant songwriter and a great singer, and had something to say.

Kirk Hammett: In terms of the overall package, it was so complete with Jimi. He had everything going: the look, the sound, the songs, the technique, the attitude. It’s amazing how much music he created in that brief four-year window that he was around. It’s just amazing.

Don Felder: The first time I heard Jimi Hendrix I had no idea who it was, but it was magical. His style, his tone, his vibrato, his voice – everything was unique. And those people with a unique approach to playing, writing and singing are the ones that go on to be legendary. Jimi Hendrix was one of the greatest players and most innovative musicians to come along in our generation.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Ernie Isley: When Eric Burdon and The Animals first came to the United States in 1964 and happened to do some shows with my older brothers, they were saying, “You know the Isley Brothers with that one-two punch of Shout and Twist And Shout. They’ve got a very dynamic live thing that they’re doing. Who’s the guitar player they’ve got? Not the right-handed guy, the guy that’s left-handed?”. That was Jimi Hendrix. Chas Chandler, who was a member of The Animals, turned out to be Jimi’s first manager.

Bradley Pierce (promoter): The first real disco on the East Side of Manhattan was Ondine’s in the beginning of 1964. They used to have house bands, but I used to bring in groups from elsewhere because London, San Francisco and Los Angeles were where it was happening. In New York we had the Lovin’ Spoonful and the Young Rascals but that was about it. So I imported groups from California.

The Doors came first and then Buffalo Springfield. I booked Jimi locally. Actually Olivier [Coquelin, owner of Le Club in New York] recommended him to me. He told me about this group, Curtis Knight & The Squires, but mainly about their guitarist, Jimi Hendrix. Curtis was basically imitating James Brown, but he wasn’t really that good. I told Jimi he should get himself into another group. I told him that if he quit Curtis Knight he could come and play at Ondine’s and I’d feed him and pay him something.

Graham Nash: I first met Jimi in 1965, when he was playing guitar in Little Richard’s band. It was the first time The Hollies had been to America, and we played at the Paramount Theatre in Times Square. We did about 10 days there on a bill that had around 20 acts on, five times a day. And that’s when we first became aware of Jimi. Even in those days, and under those circumstances, he absolutely stood out.

Micky Dolenz: The first time I saw him play was at a club in New York City called the Café Au Go Go. He was playing guitar for John Hammond. Somebody had brought me down there and they said, “You gotta come hear this guy play guitar with his teeth!”. That’s all

I was told. I remember seeing John Hammond on stage and there was this black guy, this young kid playing guitar with his teeth.

Bill Wyman: I saw Jimi first at a club in Queens in New York when he was just known as Jimmy James. It was bizarre because he was doing things the average person wasn’t doing, though I knew they’d been done before: playing guitar round the back of your head and biting strings. Charlie Patton used to play guitar between his legs back in the 20s. T-Bone Walker did it all through the 40s and 50s too. So it wasn’t new, but it was new to a different audience. He’d already been around and paid his dues in bands with Little Richard and Ike Turner. Jimi was a nice guy. All the Stones got on very well with him.

Bob Kulick: In 1966, I was 16 and my band, the Random Blues Band, played at the Café Wha? club in Greenwich Village. One day we were told this guy was coming down to audition and the name of his band was Jimmy James & The Blue Flames. So we watched as this guy came in and started to set up his gear. He was asking about using two amp cabs together and we all looked at each other like, “What? How do you do that?”.

On stage he had all these pedals and I thought, this should be interesting. He had a very interesting look. He looked like a star. The band started playing what sounded like a prototype of a Third Stone From The Sun kind of song, and within one minute you knew that the guy wiped the floor with everybody we’d ever seen play. By the end of his set when he played solos with his teeth that nobody could play with their hands, we knew this guy was a sensation.

Bill Wyman: When we got back from America, I bumped into The Animals at the Scotch of St James, where we all used to meet up with The Beatles and The Hollies and various bands. Chas [Chandler] said to me: “We’re off to the States next week”. I said: “If you’re in New York, go and see this guy called Hendrix. He’s fantastic”. So they went, Chas met him and then signed him and brought him over. But Jimi had to come here to become famous.

Robert Wyatt: I remember Chas [Chandler] coming in to the office and – I can’t do the wonderful Geordie accent – he said, “I’ve just found this fucking guitarist. He plays the guitar with his fucking teeth! He’s unbelievable and we’re gonna get him!”

Upon arrival in the UK on September 24, 1966, Jimi’s new manager Chas Chandler introduced him to the London music scene, where, over the following months, Hendrix would make his presence known by jamming with other players. On October 6, the Jimi Hendrix Experience – completed by Mitch Mitchell on drums and Noel Redding on bass – would hold their first ever rehearsal.

Andy Summers: I was living with Zoot Money at his house in Fulham, Gunterstone Road. There ought to be a blue plaque on that house for the number of people who passed through in the 60s. It was like the party house for the London scene, every night.

I’d heard about Hendrix before I met him because we were quite tight with The Animals, and Chas Chandler – who I was sharing a girlfriend with at the time – called me and said that he’d found this fantastic blues guitarist in New York and he was going to bring him over, and he wanted me to come and see him play.

The apocryphal story is that when Chas and Jimi arrived at Heathrow, they came into London to go and jam at a party somewhere and they passed by Zoot’s and my flat on the way. That’s true, but I wasn’t there. They searched all round my room looking for my guitars, which I think I’d hidden under the bed. In the end Zoot had a left-handed acoustic guitar which is what they went off with.

Jeff Dexter (DJ and club promoter): I first met Jimi the night after he arrived at the Cromwellian Club. He was charming, very polite, well-spoken, flabbergasted to be in London and didn’t look anything like the wild Jimi Hendrix in all his gladrags. It took a couple of days to get him dressed up, but everyone was making a fuss about him. I didn’t really get it, because to me he just seemed like another American in town.

Then he mentioned that he’d played with Joey Dee & The Starliters [Hendrix was in the band briefly in late 1965] and that’s when my ears pricked up. I thought that if he’d played with them then he must be great. They were a big influence on me, so I was more interested initially in talking to him about Joey Dee & The Starliters. Then we moved onto Bob Dylan. It had been the summer of Blonde On Blonde and, for anybody who cared about music and poetry and what was really happening, that was the event of the year. That album was inspirational for lots of us.

Dave Mason: I first saw Jimi Hendrix at [Mayfair club] the Scotch of St James. It was just after Chas Chandler had brought him over and he took him round those little clubs. He got up and jammed with this band and I just happened to be there. At that point nobody knew about him. Chas was doing something very unusual and very smart in that he purposely introduced him to the London inner circle of musicians by bringing him down to some of those clubs and saying “Go sit in”. And that’s how I first saw him.

There were plenty of British guitarists on the scene: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Peter Green. But there was no Hendrix. I watched him jump on stage with somebody and do everything that they could do, and then play with his teeth. He was a showman. The English guitarists were busy mastering the blues, but Jimi had already done that. He was past all that stuff. Andy Summers I got to see him a few days later at [Kensington club] Blaises where he was jamming with Brian Auger. He was up on stage wearing a white buckskin suit with these incredibly long fringes, a huge Afro and had this white Telecaster that, as I walked in, he was playing with his teeth. The guitar was wailing away, and I just stopped and stared. I was riveted, gobsmacked.

And I think it was the same for all the musicians who saw Hendrix at that time. Even the established star names guitarists like Clapton and Beck. There was a whole paradigm shift. He seemed to come from a much more authentic, savage place. It wasn’t some English guy trying to copy what they thought was going on in America, it was the real thing.

And it had arrived on our shores. A lot of the English guys were so snobbish about the blues. But Jimi wasn’t paying homage to any of the legends, he was doing his own thing. He’d taken it to another place. He had such an incredible feel for what he was doing, such a sound and such an attitude. There were no English reservations, that’s for sure.

Musically he played with a phrasing that was completely different. It was Hendrix – it wasn’t BB King or Freddie King, it was him. He was much wilder and played more freely than anyone else. And that’s what turned everyone on and got everyone talking. It was like, ‘Have you seen the new model?’

Brian Auger: There was one night at Blaises [September 1966] We’d just finished our set and Jimi had sat in, and he was leaving the club. The club was in a basement, so there was a big flight of stairs down, and then his girlfriend ran in saying: “Brian, you’ve got to help Jimi! There’s these guys who are threatening him!”. This was a very strange thing to happen in London at that time, because it didn’t matter what colour you were, man.

So I told my roadie and a couple of guys from the band and we all went, a crowd of us, to the bottom of the stairs and looked up and there were these four huge South African guys – they looked like rugby players, all white guys – and they were shouting to Jimi: “Come up here, kaffir!”. We basically told them to fuck off, and fortunately for us, they actually did. A cab drew up and they decided they’d leave. I’d never seen anything like that in London.

Arthur Brown: Jimi’s blackness was a thing. There was a lot of racial prejudice around – but then Otis Redding was the god of the Mods. Plus there was the Alexis Korner Marquee scene with all the black soul giants. And the Flamingo Club playing blues and Jamaican and calypso. There were prejudicial ideas, ‘What’s a black guy up to, compared to a white guy?’. But having the two white guys in the Experience meant he couldn’t just be written off. There was unconscious racism around in the 60s, but Hendrix helped a lot of that turn around, certainly in the underground scene.

Stephen Stills: Jimi and I were hanging around together, hitting the clubs in England and going to the Bag O’ Nails and taking over the stage. And it graduated to me and my friend Dan Campbell joining him. Maybe because Dan and I were both southerners, Jimi so missed talking to an American face that really understood black people. So he’d pour his heart out and we’d talk about everything under the sun. He’d steal away from his usual retinue and come talk to us.

Ginger Baker: We, Cream, were doing a gig in a theatre in London and Jimi turned up to sit in with the band at the Central London Polytechnic [October 1, 1966 – leading them through an incendiary version of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor, complete with behind-the-head picking and flamboyant splits – most of his moves copped from Eric’s hero, the blues legend Buddy Guy].

I was totally against it. I didn’t want him to sit in at all because I didn’t think it appropriate. We were fine without him. I didn’t know who he was or anything and when he did sit in I was not at all impressed; he was doing all that playing guitar with his teeth and rolling about. I really don’t know if Eric and Jack were impressed. I know Eric liked him. To me he was being the big showman, whereas Eric just stood there and played. He was a great player.

Jack Bruce: I was just having a pre-gig pint in a pub across the road and in comes this guy who turns out to be Jimi Hendrix. Now, we had already heard about Jimi on the grapevine. Jimi came up to me and said: “Hi. I would like to sit in with the band”. I said it was fine with me but he’d obviously have to check it out with Eric and Ginger. So we went across to the gig, and Eric immediately said yes and Ginger said: “Oh, dunno about that” [laughs]. So he came on and plugged into my bass amp, and as far as I can remember he just blew us all away.

Keith Altham (journalist): “I gotta go and see Clapton,” Jimi told me during an early interview, adding with a sly smile: “I wanna see if he is as good as he thinks I am”.

Andy Summers: Hendrix led the way into psychedelia in many ways. The London scene had been coming along and you had The Beatles, of course. Clapton was getting into Cream and Beck was doing various things, and then out of the fucking blue comes Jimi Hendrix. He fired everyone up. We all started writing songs and growing our hair longer. What a time to be a young musician.

Neal Schon: Jimi was so extraordinarily gifted. He was just seeing things so vividly. A lot of times when you’re creating, you have to imagine things before you play them. And the only way I can imagine Jimi came up with a lot of his music was to vividly see it in his mind before he would play it. He would see the landscape and then create it.

He was a definitive innovator of electric guitar, making sounds that nobody had ever heard before. And the music he made is timeless.

Eric Burdon: I wouldn’t say anybody was a close friend of Jimi’s. He was a strange guy,

a loner. I think I got as close as anybody could do, though. As luck would have it, we were managed by the same people. But what started out as a really beautiful period of my life and a great friendship turned into a real tragedy. It’s still something I think about on a bi-daily basis. Once a week, Hendrix creeps back into my life. Every guitar player who auditions for me wants to impress and play like Jimi. That gets on my nerves. It’s difficult to find a guitar player these days that isn’t influenced by Hendrix.

Graham Nash: Mitch [Mitchell] used to share my flat for a while in London. He had nowhere to live for a strange period at the beginning of the Experience and I had an apartment, so he just came to live with me for about a year. I’m not a jammer, but Jimi would come around a lot and we’d listen to music. Though most of all we’d play Risk. Nobody could beat him! Jimi would drop a few tabs of acid and that was it – nobody could beat him at Risk.

Jeff Dexter: I remember we went to the Bag O’ Nails one night – Jimi had already got up and played a couple of times at the Bag. We sat down at the table to watch the band and chat with Al Needles, who was the disc jockey. Suddenly we got ordered off this table because we weren’t the kind of people to spend money on champagne. A bunch of heavy spenders had come in, so they shifted us off to one side. Jimi said: “Don’t worry, man, one day I’ll come back and I’ll buy that table!”.

Arthur Brown: The vibe around him in London? People were gobsmacked. Certainly all the guitarists were afraid. The extremes of sound – his use of wah-wah and the whole emotion he played with – was a brand new thing. Everyone was put on their mettle. The generous ones were delighted, and the not so generous got jealous of him. He used to shop down Kings Road for all the outrageous clothes. He was vital to that whole scene. Plus he was so sexually available that he had a real energy. People who would have written off others as psychedelic namby-pambies saw his photos with his abdominal muscles and decided we don’t mess with this guy.

Graham Nash: Jimi was very different from the outward image that the public knew. He was very intelligent and a shy, humble man in many ways. But he created this wild man sex object persona, who happened to play the most unbelievable guitar in the world. His image became almost a trap for him. And I think that in his later years he tried to just play music rather than play up to this wild-man image. I’ve heard talk about Jimi and I writing some songs together at one point, but that’s completely untrue. That didn’t happen.

After wowing the London scene and a brief sojourn to France supporting Johnny Hallyday, the Experience knuckled down to make their debut album, Are You Experienced. It would be released in the UK on May 12, 1967.

Eddie Kramer: Jimi had already been in London for a few months when I met him. He’d already had a single out [Hey Joe]. He’d already played the Paris Olympia, so I really did know who he was. Everybody knew who he was and what he was doing – turning the music business upside down. I get a phone call from my lovely studio manager named Anna Menzies. She called me up and went [adopts tremulous posh English voice], “Oh, Eddie. There’s this American chappie, with big hair and you should do the session because you do all that weird shit anyway”. Because I had this reputation for doing a lot of avant-garde jazz, so she thought it would be a good fit. And she was right. We hit it off.

They’d actually cut a few tracks, but when we started the sessions at the new Olympic Studios in Barnes, in January 67, it was a revelation for Jimi because a) it was a fantastic studio, and b) not only did we hit it off in terms of an intellectual level, an emotional level and also a musical level and all that, but we were able to create different sounds for him that he wasn’t able to get in the other studios. So we ended up overdubbing stuff on some of those tracks they’d originally cut. Then of course we dived right into the new album and started cutting new songs. We virtually finished up the record there at Olympic and mixed it there.

Mitch Mitchell: As for the burning of the guitar, [Monterey] wasn’t the first time that Jimi had done it. The first was at Finsbury Park Astoria in London, which later became the Rainbow. As usual in England, we got in trouble with everybody over it.

Keith Altham: I came up with the burning guitar idea in England, because Chas asked me what he could do to steal the headlines on the gloriously incongruous Engelbert Humperdinck-Walker Brothers-Hendrix package tour opening at Finsbury Park Astoria. It worked. And Jimi was not undyingly grateful, as a blazing conflagration was expected of him on every performance. And as he said to me before going on stage at Monterey: “I got an idea Keith – why don’t you set fire to your typewriter tonight for a change?”.

Leslie West: I was first aware of Hendrix when I plugged my guitar into an amp and someone gave me a copy of his debut album Are You Experienced and I said: “Boy, do I suck”.

Andy Summers: I saw the Saville Theatre [June 67] gig where Jimi opened with Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band when the album had only been out for a couple of days. It was quite incredible. Brilliant. It just blew everyone away. And I remember seeing him later at the Hollywood Bowl where he came on and started with Sunshine Of Your Love. Which confounded everyone who assumed that there was this big rivalry between Hendrix and Cream. But Jimi was not like that. Mind you, he played it better than Cream. But then he seemed to be able to Hendrix-ify any song that took his fancy. He did it particularly with Dylan, first taking Like A Rolling Stone to another place and again, brilliantly, with All Along The Watchtower.

Rick Springfield: What Jimi Hendrix means to me is innovation and bravery. When I heard the first Jimi Hendrix Experience album I couldn’t believe how heavy it was. This was still a time of mainly pretty pop all over the charts and Hendrix comes out of the gate with Fire!

Ginger Baker: We did lots of gigs that Jimi was also on, so we met up many times. There was a good one I remember at a festival in Lincoln at the Tulip Bulb Auction Hall in Spalding [May 29, 1967]. At that time Polaroid cameras had just been invented – you could take pictures and instantly see them. Mitch Mitchell was running around and taking pictures of Jimi with various chicks at the Red Lion Hotel, where we were all staying [the Experience, Cream, Move, Pink Floyd]. He sprang to everybody and he had a reputation, there was just chicks everywhere climbing up knotted sheets to get to his room.

In the summer of 1967 Jimi Hendrix returns to the United States with the Experience. On June 18 they play their definitive set at the Monterey Pop Festival.

Al Kooper: I met Jimi at a soundcheck at the Monterey Pop Festival where I was the stage manager. We spoke in the wings and he invited me to play with him that night on Like A Rolling Stone, but I had to turn him down because I was working, and [promoter] Lou Adler would have got very mad at me if I’d ducked out. You don’t want to fuck with Lou Adler. Every inch of me wanted to do it.

Mitch Mitchell: My overriding memory of Monterey is such a happy one. It was the first time I’d ever been to America. I can’t tell you what a big deal that was for any English musician, really a dream come true. It was better than I imagined. The beauty of California, the sunshine, light and warmth after England was just magical. The American people showed us nothing but kindness and open friendliness that you just don’t find anywhere else. Even the motorbike police at Monterey let people attach flowers to their caps and bikes. Not a thing that would happen in England.

David Crosby: Our paths would cross a lot of the time. We jammed with him, played with him and hung out with him. We loved him. We thought he was the genuine article, which of course he was. As flamboyant as Jimi was on stage, he was shy and quiet in person. He wasn’t at all like the figure you saw up on there on a stage. But if one of his hands could touch the guitar, Lord have mercy! Because you just didn’t want to get in the way. He was spectacular. I remember watching him play Foxy Lady at Monterey and it was almost too fucking good.

Micky Dolenz: I knew about Jimi before Monterey Pop, but I’m sitting there watching all these great acts at the festival – Ravi Shankar, The Who, The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield… The announcer said: “Here we have the Jimi Hendrix Experience!”. Out come these three guys looking really cool, like circus performers wearing very psychedelic outfits. They start playing and I did a double-take when Jimi started playing guitar with his teeth. I said to whoever I was with, “There’s that guitar player that plays with his teeth!”

I recognised him from seeing him in a little club in New York City. He was amazing at Monterey. I remember just being bewildered and in awe of his musicianship but also impressed by the showmanship because it was a very theatrical sort of performance. Like with The Who smashing guitars and drums. After the show, Jimi and a couple of other guys were in the one of the tents jamming until the wee hours of the morning on the last night. I was there watching all of that go down and remember being in awe.

DA Pennebaker (documentary film maker): John Phillips of the Mamas & The Papas knew about Hendrix beforehand. At that time he was not known in America. John had told me about him and said, “This is a guy who plays blues and sets himself on fire” [laughs]. I said, “That’s the kind of blues I guess I’ve never heard”. I didn’t know what to expect but I would soon find out at Monterey Pop Festival. In America, some underground radio stations were playing Hey Joe. But a lot refused to play it because it had to do with either suicide or murder. In those days people were very cautious about what kind of rock music they played on the radio.

Mitch Mitchell: For Jimi, Monterey was so special as well. He was going back home with a band he felt was something special, and playing with Jimi was always instinctive. He gave complete freedom and I would have to say there was a very close link. We knew The Who were going to be a tough act to follow. Nobody would want to follow The Who on stage – they were just so great – but having said that we had faith in ourselves and felt we had something good too.

Micky Dolenz: At that time we were looking for an opening act for the upcoming Monkees tour. I told the producers of the television show: “We’re looking for an opening act. I gotta tell ya, this act I saw at the Monterey Pop Festival was great!”. Besides the music, which

I loved, the reason I suggested Jimi was because he was very theatrical and so were the Monkees. I thought it would be a good mix.

Mitch Mitchell: Monterey really changed everything for us. We had nothing at all after Monterey, not one gig planned. But after Monterey we got loads of offers: the Fillmore, the Hollywood Bowl with the Mamas & The Papas, who were just terrific to us. It was really the start of everything. Besides we wanted to do well. Paul McCartney liked the band early on and suggested us for the gig. We didn’t want to do anything but our best.

Bradley Pierce: I didn’t hear from Jimi for some time, not until I was in California looking for a group to play at the opening of [New York nightclub] Salvation. I asked Jimi what he had been doing and he told me about his new group, the Experience, which I had never heard of because, although he was already big in Europe, he hadn’t broken America yet. He said I should come and see them at Monterey Pop. I knew that wherever Jimi was, that it would be exciting, however good the other two guys were. So I asked him there and then if he was free to play at Salvation when I opened. In the end, right after Monterey, he came and played two weeks at Salvation for nothing. I literally passed the hat in the club to get some money for them.

Micky Dolenz: Chas Chandler must have also thought The Monkees tour was a good idea as, I assume, did Jimi, Mitch and Noel. Lo and behold they started opening for us. We were in awe of him. So much so that we very seldom got to the arenas much before we went on, but I remember going early many times to watch Jimi play. Mike [Nesmith] was totally blown away by him. Jimi was a great guy, quiet, naïve and gentle. We hung out a lot after the shows and in hotel rooms on the road.

Steven Stills and Graham Nash showed up. After one of the shows, I remember being in a hotel room with Jimi, Peter Tork and Steve Stills was there and a bunch of guitars. I started strumming on a guitar along with those guys and they’re playing all these amazing leads. I was just playing a rhythm guitar part. That song must have gone on for at least a half-an-hour.There was a whole bunch of people in the room – girls and roadies –and these guys are on fire jamming. I just stopped to go to the bathroom and they all stopped and they looked at me and said, “What did you stop for?”, I said, “I didn’t think anybody was listening”.

Bob Kulick: The night the Jimi Hendrix Experience was fired from The Monkees tour he had a party in New York City and invited a bunch of us to hang out with him. Here was the conquering hero returning from England where he’d gone from Jimmy James & The Blue Flames and turned into the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was a ‘Holy shit! Oh my god!’ moment.

So we went up there and met Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell. These guys were lit up. I hadn’t seen the Jimi Hendrix Experience play yet but knew their record. I remember Jimi had a stack of 45s and a turntable. He wheeled us through all of the newest English music. The only artist that mattered to me that he played was Tales Of Brave Ulysses by Cream. We heard that song and saw the look on his face. Jimi immediately made the comment, “This guy is a better guitar player than me”. That’s what he thought of Eric Clapton, and Eric Clapton thought that way about Jimi.

Micky Dolenz: As for the crowd reaction to Jimi opening for The Monkees, it wasn’t that they didn’t dig it. They didn’t boo Jimi off the stage. That’s part of the urban myth. It just wasn’t the music for a 10-year-old little kid. We loved it and I’m sure some of the older kids and parents dug it. So it wasn’t that they didn’t dig it, they were just there to see The Monkees. It wasn’t like the crowd were screaming, “You’re terrible! Boo! Get off the stage!”.

It didn’t matter who was up there . They were screaming “We want The Monkees. We want The Monkees! Micky! Davy! Peter! Mike!” even before the opening acts went on. It was embarrassing for me. Jimi sort of laughed it off until I think he just got fed up. His first record was breaking at the time, so I like to think he got some good exposure. I have no doubt Jimi Hendrix would have been Jimi Hendrix with or without the Monkees tour. We hung out a lot up until the last gig, which was in Forest Hills. Afterwards, we went to the Electric Circus club in New York right after that show.

Henry Diltz (photographer): Unfortunately, I didn’t get to see Jimi perform on The Monkees tour as I showed up on the last date he played with them in Forest Hills, New York [July 19, 1967]. Ironically, I showed up just as he was coming off the stage. It was an afternoon show and later we all hung out at the hotel. Everybody was out in the hallway and I remember someone handing out little white pills, which I found out were psilocybin [natural psychedelic]. We all took them and got very high.

Nils Lofgren: I saw the Jimi Hendrix Experience play a lot and it was incredibly inspiring. I saw him for the first time in Washington DC in [August] 1967 and that’s what inspired me to try a career as a musician. We idolised The Beatles and Hendrix but you didn’t think you could ever do that for a living in Middle America.

Henry Diltz: I photographed Jimi when he headlined the Hollywood Bowl. They had a large wading pool right in front of the stage and the front row was behind that. They’d have coloured lights in the water with water squirting up at times so it was kind of a fountain pool. I was crouched at the edge, looking across at Jimi, taking photos and suddenly I was aware of someone jumping up on edge of the pool next to me.

That person jumped into the pool and I thought, ‘Wow, that’s strange’. Suddenly a whole bunch of people jumped in. It was like those documentaries on wildebeests jumping into the river. At some point there were 20-30 people in the water wading up to the front of the stage with their arms flailing. Jimi bent over at one point to say something to them. I think he was concerned. Very quickly they stopped the concert because if a microphone or an amp fell into the pool those people would have been electrocuted.

While much of 1967 was spent on tour, the Jimi Hendrix Experience managed to find time to sneak in sessions at Olympic Studios in London in May, June and October to record their second album, Axis: Bold As Love. It would be released on December 1.

Rick Springfield: Axis: Bold As Love is where Jimi demonstrated what you could do if you turned the guitar down and used tone. He turned the world on to Strats and showed what a melodic solo truly was. Hendrix changed music and guitar playing in particular forever. Not bad for the first two albums. I still don’t know where those first two albums came from. They were magic. And he had the authenticity to make phrases like ‘comin’ to gitcha’ sound so real, you never questioned that he was posturing or faking it.

Trevor Burton: The Move were recording at Olympic Studios and next door was the Jimi Hendrix Experience recording their second album. Roy [Wood] and I walked in to say hello because we knew them well by then. They were doing You Got Me Floating and Noel and Mitch weren’t cutting the background vocals too good, so we asked Jimi, “Do you want us to have a go?”. And he said, “Yeah!”. I think we did it in two takes. Jimi was pleased with it. He sang his lead vocals live at the same time while we put down the background vocals.

Eddie Kramer: When you look at the progression of the albums and what Jimi was saying lyrically, musically, all of that stuff, you really get a sense that Are You Experienced starts the ball rolling. It’s very raw, very in-your-face, very primitive. Then Axis… being the next stage of development where things are more experimental. I’m expanding the stereo imagery, the sounds are better. And the songwriting is much more experimental too. In the first part of 1968, the Experience found themselves back on the other side of the Atlantic for yet more gigs, including a Martin Luther King Jr wake and the Miami Pop Festival. In February, Jimi had the honour of having a certain part of his anatomy immortalised by Cynthia Plaster Caster…

Cynthia Plaster Caster: It was at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in Chicago, February 25, 1968. In between two concerts they were doing at the Civic Opera House that day. I wasn’t a real big, humungous guitar aficionado, but I really got off on Jimi’s guitar. We’d been experimenting with trying to figure out how to plaster cast anything, namely penises, after I’d gotten the idea from my art teacher two years prior. The only thing missing in the formula was what mould to use to make a negative impression. There were all these substances I was trying that were not very conducive to the prettiness of a penis, but I’d heard about dental moulds and that seemed to be the best bet. I tried it a few times on a couple of friends because I wanted to be ready for Jimi Hendrix, and know how to do it.

DA Pennebaker: I met Jimi later at a club in 8th Street in New York City where there was a wake being held for Martin Luther King who’d just been tragically killed. All hell was breaking loose in the city; they were tearing New Jersey apart and Harlem was blowing up. We set up an Ampex tape recorder in a booth in the back and were going to record everything and I was gonna film it.

Jimi was there because he was one of the performers. It may be hard to believe but he did the sound recordings on my Nagra recorder while I shot the event. Jimi did my sound! We have a picture of him holding the slate in the film, which we’ve never released. It was a really grim day. The last song they played that night at the Martin Luther King wake was Dylan’s All Along The Watchtower and it was dawn. Everybody got up on stage to perform it – Janis Joplin, Hendrix. It was a very powerful moment.

Arthur Brown: We did various festivals together - like Miami Pop Festival, some shows in Scandinavia and Germany, a whole series with Zappa, Hendrix and myself in America after the Fire success. At Miami Pop I took a ride in Jimi’s helicopter and grabbed a ride on Noel Redding’s motorbike. We hung out. That was the whole deal back then. We met at the Speakeasy for dinner and I’d sit with him. He was quite electric. He was ingesting various substances and the effect on ladies was extremely powerful. If a waitress walked by, then Jimi’s hand would appear and he’d be touching her on the arm, or somewhere else. He was very available to ladies and they fancied him a lot.

Billy Gibbons: We toured with him most in 1968. It was a real mind-bender and eye opener, to say the least. As most now know, Hendrix, either consciously or subconsciously, made a decision to invent things to do with a Fender Strat that it had not necessarily been intended for. He did it very well, too. I was 18 at the time, and somehow the organisers saw fit to book us in the hotel room across the hall to his room. That was convenient to allow me to ask him the obvious question: “How do you do that?”.

Jack Bruce: Hendrix had a positive effect on everybody, especially guitar players. He came to the sessions when we did White Room in New York and was very encouraging. He came up to me and said, “Wow, I wish I could write something like that”. I said, “Jimi, what you’ve got to realise is that I probably nicked it off you!”.

Arthur Brown: I used to play with him at the Scene Club in New York. I was there with the Crazy World when Chris Stamp brought him along to see me. At other times it would be jams with all kinds of musicians, big names, or not so big. We would jam and he would play bass on those occasions. He didn’t like singing. Even if I offered him the mic he wouldn’t do it.

From those sessions he came up with the idea he had of us forming an actual band. We didn’t come up with a name. It was going to be a band with tapes of Wagner in the background. He was aware that he’d had these commercial hits and as far as the audience were concerned he needed to move on musically. He wanted a stage show with a theatrical performance via me singing. He wanted huge projections on the screens and Vincent Crane on keyboards. The rhythm section was to be the Experience, so we’d elide the two bands. It was a continuum.

Nils Lofgren: On one of my first New York adventures, I went to this famous nightclub called The Scene. After a show, I was hanging out and there was late-night jam session, where I somehow found myself up on stage at two in the morning, with a broken string and a bunch of other musicians. I suddenly realised Jimi Hendrix was at the back of the room, with this black bolero and his bullfighter-type clothes.

At some point he got up and I could see through the smoky haze that he was coming towards the bandstand. Next thing I knew, he was standing right in front of me. Like an idiot, I didn’t know what to say. Then he asked the bass player, who was standing next to me, if he could play bass. I was just freaking out. Here I was – 17, a broken string and I suck – and I’m going to play with Jimi Hendrix! To my amazement, the bass player turned him down: “Not now Jimi, I’m groovin’!”. Jimi asked twice more if he could play bass, and the guy said no. So that was my near miss of jamming with Hendrix.

Neal Schon: I saw Jimi in concert in 1968 at Winterland in San Francisco. He played three nights – Friday, Saturday and Sunday –and I saw him on the Sunday. The Friday, I heard, was extraordinary. The Saturday I heard was very good but he was sticking the neck of the Strat into the speaker cabinets, and he wouldn’t replace the cabinets. So when I saw him on the Sunday it sounded like a bunch of blown-up speakers. He looked amazing and he looked like he playing amazing, but the cabinets had just had it. But the guy had incredible charisma like nobody else.

Between gigs, TV shows and, er, ‘castings’, the Experience recorded what would be their final album in sessions at Olympic Studios, London and Record Plant Studios, New York. Electric Ladyland would be released on October 25, 1968.

Al Kooper: Working on Electric Ladyland I didn’t see any evidence that he’d fallen out with Noel Redding. I was only there for a three-hour session. We recorded Long Hot Summer Night from scratch. The song had never been done before. I got paid union scale. I played and he said, “Thanks man, catch you later on”. In the room it was his band and I. It was no stretch at all as a musician. Noel did play bass when I was in the room. Maybe that was replaced afterwards by Hendrix. Jimi sang the backing vocal tracks.

I didn’t leave the studio walking on air exactly, because we were pretty good friends prior to that. It wasn’t like when I played on Bob Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone, when I did leave the studio walking on air. After the Jimi date I just wanted to avoid the rush hour on the subway because it was late afternoon and I wanted to go home.

Ginger Baker: Jimi paid us this incredible compliment on the Lulu TV show [January 4, 1969] when he stopped what he was playing, stopped his band, and did Sunshine Of Your Love. I didn’t ever dislike him. It was just I wasn’t impressed that first time he sat in with us. That was my first impression. Cream just weren’t into showmanship at all, that’s why I was horrified at the time. The audiences loved it, but Jimi’s bag on stage was pulling as many chicks as he could. They used to congregate around Jimi like flies. They thought he was God Almighty. He had a fantastic reputation as a womaniser.

Glenn Hughes: I met him just the once. I was with my band Finders Keepers, before Trapeze. We were playing in London one night and I found myself in the famous Speakeasy nightclub. As I walked into the toilet, he was walking out. He held the door open for me. We chatted briefly and I remember him being genuinely sweet and kind. We did the brotherly handshake and “Hey man” thing. That’s all I really needed… I was star-struck because the guy was royalty. I wasn’t out to stalk him, we just happened to be going to the toilet at the same time. It’s not much of an anecdote, but at least I met him.

Stephen Stills: Between Jimi and Neil [Young], they really tried to get me playing lead guitar. Jimi would say: “You can do this! If we play together, I want us both to play”. He’d show me something and I’d have to remind him: “Jimi, your thumb is the size of my entire hand. I can’t do that!”. And he’d go: “Oh, yeah”. He’d try and teach me things, explaining how I could play a certain way, then I’d see the whole scale and be free.

Like it was so simple! It was hilarious. Some of it was just physically impossible to do. Then he’d say: “And the strength in that third finger will come. Keep trying to make the bend with that finger cos it leaves the others free”. It was the best time. I also played bass a lot of the time when we were jamming, which I was pretty good at.

Joe Cocker: I was living in a place in the Valley in Los Angeles, and I got an invite from Mitch Mitchell who said Jimi wanted me to pay him a visit at his Hollywood pad because he liked my stuff. Since he was a hero of mine I didn’t need much persuasion. When I turned up Jimi greeted me inside although the sum total of his conversation was a mumbled “Hey, how are you, man. Glad you dropped by”.

After a while he decided he wanted to jam. At that time whenever he felt the urge to play at home he had the Irish guys from Eire Apparent on tap to back him up because he particularly liked their bass player Chris Stewart. So we all went into this tiny room full of equipment and he put on a total show with me as the sole member of the audience. The space was so small I literally had my right ear wedged against his amp, which is why I’ve now got tinnitus.

Thanks for that, Jimi! He gave it everything though, played guitar upside down, between his legs, it was like a total performance. I was absolutely amazed. One thing was, he didn’t ask me to sing. I was extremely stoned by the time I left his pad. I never felt I knew him. I don’t think many people did. But I’m pleased to have that episode in my memory bank. A private concert from Hendrix? Unbelievable.

Leslie West: I’d already met him at the Record Plant in New York in 1969. He was the first to hear the Mountain Climbing! album being mixed. It was quite a day for me. I was a nervous kid when he heard the record. And then a year later I’m in the club and he walks up to me just after Steve Miller had finished playing and says: “Do you wanna jam?”. I’m like – are you kidding? I had a loft where I kept all my equipment, so we got into Jimi’s limo and went down there. I couldn’t get over him. Steve Miller missed out because he’d already left, but his drummer Tim Davis had hung around and he played drums. A lot of my friends are very jealous I got to play with Jimi and they didn’t.

Mick Brigden (musician): One fabulous night Leslie brought Jimi up to our rehearsal studio. I watched them noodle away for a couple of hours and rolled them their joints. This was in a funky area on the East Side of Manhattan on the West 30s by the Lincoln Tunnel. It was around midnight and there was a bang on the door. I looked down from the second floor window and there was a stretch black Cadillac limo parked up with Leslie standing on the street. Leslie bowls in saying: “Hey Mickey, say hello to my friend Jimi”, and coming out of the limo was Hendrix. He gave me his soft handshake and slides past me like a puff of smoke.

I was in shock. Jimi Hendrix has come to visit me in the middle of the night? Fine. I’ll remember this. Hendrix says: “We just want to jam, and hang out for a while. Can you set us up? Then we’re going off to this club”. I got together a quick array of Union Jack rehearsal amps for them while they got their thing together. They sat down and jammed while I sat on the bed. Both guys had a traditional electric blues style so that’s what they played. Jimi didn’t play Foxy Lady or anything. It was blues progression jamming.

At the Denver Pop Festival on June 29, 1969, Jimi would play his last gig with the Experience. Already committed to play Woodstock, Hendrix put together a new band – Gypsy Suns & Rainbows – with old army buddy Billy Cox on bass, Mitch Mitchell on drums, rhythm guitarist Larry Lee and percussionists Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez.

Mitch Mitchell: Woodstock for us – while it means so much to many people and I don’t want to denigrate that in any way – was mud, tiredness, logistical problems on an epic scale and just difficult. Juma Sultan Jimi had been jamming with guys, auditioning guys every night. I knew all the musicians in the area. With Woodstock approaching, Jimi knew he had to tighten up, and he was committed to that contractually. Maybe a month before the festival, Jimi called in Billy Cox and Larry Lee, the guys that became Gypsy Suns & Rainbows. We started rehearsing every day. Mitch didn’t come in until the tail end, and he was drunk most of the time and did not really rehearse with us. That was the situation.

Ernie Isley: There was a show we were going to do in June of 1969, that we did at Yankee Stadium in New York. My older brothers wanted the Jimi Hendrix Experience to perform, and they asked him. His reply was, “Oh yeah man, cool. I’d love to do it, but let me talk to my people and I’ll get back to you.” And a few days went by and he called back and said, “Man, I’d love to do it, but there’s this thing called the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in upstate New York in August and the promoter don’t want me to play in the New York area before this Woodstock thing”. Other than that, he would have been at the Yankee Stadium show.

Henry Diltz: The last time I photographed Jimi was at Woodstock. He went on stage Monday morning. The dawn was just breaking and these colourful guys came out on stage. It was eye-opening because we’d been up all night and had been watching music for three days. Jimi had that white fringe jacket. The high point was the moment he launched into The Star-Spangled Banner solo on electric guitar. That was the best moment of Woodstock for me. It was awe-inspiring to hear this beautiful and piercing rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner with sound effects – airplane dive bombing, explosions and machine-guns.

There was the Vietnam War, which we were all morally against, and here he was playing this patriotic song. You stopped and felt, “It’s our song too. It doesn’t belong to the government or the establishment, it belongs to all of us”. There was a very tribal feeling there because it was the biggest assemblage of hippies and anti-war, peace-loving people. I happened to be standing about 10 feet away from Jimi when he was playing that song. I was speechless. It was so magnificent and moving and it’s a memory I will never forget.

Kirk Hammett: I just recently bought Live At Woodstock, and I’ve watched that clip over a hundred times, and every time I find something different: a nuance or little group of notes I hadn’t noticed previously. I really like the three-song medley of The Star-Spangled Banner, Purple Haze and Villanova Junction. And I mean, seriously, his version of Star-Spangled Banner... there’s absolutely nothing like it.”

Leslie West: I saw him go on at Woodstock on Monday morning at seven o’clock. He was the unofficial headliner, and the reason why Mountain were on that festival at all was because we had the same agent, Ron Terry. Ron told the Woodstock folks if you want Hendrix you gotta take this new group called Mountain, so he kinda shoved us up their ass

On June 12, 1970 Jim Hendrix would release the Band Of Gypsys album, a live album recorded at Fillmore East. The band – with Buddy Miles and Bill Cox – would also record briefly in the studio. Two months later, Jimi would return to Europe to perform at the Isle of Wight festival and the Love And Peace festival in Germany.

Tommy Ramone: I worked from 1969 to 1970 as an assistant engineer at the Record Plant in New York City. I knew somebody at another studio who got me connected with the Record Plant. That period was a very interesting period for Hendrix. He had changed musicians – out were Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, and in on bass was his friend Billy Cox and Buddy Miles on drums. It was a whole different atmosphere.

The producers were also different. He brought in Alan Douglas and his assistant Stefan Bright. I think Jimi was going through all kinds of changes and turmoil at the time. It was a strange atmosphere. Jimi was a perfectionist in the studio. He would never settle for second best. He was very hard-working and serious about his music. He would do all kinds of things to make a song happen. Some of the sessions I worked on were songs like Izabella, Freedom, Dolly Dagger, Stepping Stone, EZ Rider and Machine Gun. It was exciting to meet him, but what was even more interesting was how charming he was. In between songs he could be very playful. He always wanted to please you. He wanted to please me and I was just the assistant engineer!

Steven Tyler: I never met Jimi, but our paths crossed in the studio once. There was a Telefunken pencil mic I wanted to use, and the guy comes over and says, “You don’t want to use that mic”. And I go, “Why?”, and he goes, “Hendrix used it”. I said, “Well give it to me!” and he says, “You don’t know how he used it”. I said, “What do you mean?” and he said, “He was in that bathroom over there. We had a tape of him. He took that microphone and he put it in a girl’s pussy. We were taping it the whole time”. I listened to the whole session, and I was like, “Whoa”. At the end, he goes, “What’s your name again, honey?”. I’ll never forget it.

Brian Auger: In 1970, I was in New York and I got a call from John McLaughlin and he said, “You should come down and listen to the mix of my album, I know you’re going to really dig it”. So I went along. Then the door opens and who should come in but Jimi and his girlfriend. We hadn’t seen each other for a long time.

But the thing that bothered me was that his skin tone, and that of his girlfriend, it was kind of a pallid grey colour. And I thought, “Whoa, he doesn’t look too good here”. We were talking and he asked me, “Listen, Bri, can you stay and make an album with me?”. And I said, “I’d love to, man, but I have all these contracts that I have to fulfil, I just can’t do it”.

And then Jimi pulls out of his pocket this silver paper, opens it up, and there’s this brown heroin in there, and he takes a snort of that, gives it to his girlfriend, and then says, “Oh, sorry, Bri”, and tries to hand it to me. This is one of those moments I’ll never forget. I said to Jimi, “Hey Jim, I’m telling you, man, you’d better quit doing that stuff, as soon as you can, because it’s gonna kill you”. And he said this to me – I’ll never forget it – he said, “You know what, Bri, I need a lot more people around me like you”. That really touched me.

Nils Lofgren: I managed to sneak backstage one time at the Baltimore Civic Centre when Jimi was playing. I had snuck into a doorway and he came down a hallway all alone, on his way to the stage. I was just taken with how emaciated and sick he looked. He could tell I was a little startled by his appearance and he said, “Well, you know, I’m not feelin’ so great.

My manager’s got me doing 64 shows in 65 days”. As a teenager, I just thought, “Well, what kind of a manager is that?”. Anyway, Jimi gave me a nod and made his way to the stage in this cloud of sadness and depression. I was really startled. It was the final years, when he was obviously getting frustrated with the whole business and I think was way too hard on himself. He didn’t have people looking after him.

Jeff Dexter: One of my defining memories of Jimi was when I was bringing him onto the stage at the Isle of Wight. His velvet trousers split as he came up the side. So I said, “Hang on there man”, went to get some needle and cotton from my record box and sewed up his pants. I’m the only bloke who had my hand up his arse, while I sewed up his trousers!

Then when he got onto the stage he couldn’t play his guitar properly because his new shirt had sleeves that were too voluminous, they hung down over his hands. So I got a bunch of safety pins and pinned up his sleeve. If you look at the film you’ll see safety pins holding up his sleeve. So he’s really the first-generation punk to wear safety pins on stage!

Ginger Baker: There was a gig we did with Ginger Baker’s Air Force and with Jimi on the Isle of Fehmarn, off the coast of Germany, which was disrupted by the Hells Angels. It was the same day that I got busted in England so I was late arriving at the gig because I had to go to the police station. We had a plane I used to fly, Air Force craziness.

The weather was terrible on the way over, violent storms, and when we got there we drove to the gig and it sounded like they were showing a Western film because there was all this gunfire and ricochets. It was the Hells Angels attacking people. So we repaired to the hotel, where there was a lot of craziness because on the way over with Jimi and the band they’d had a rare old time. We got very friendly. Jimi and I did have girlfriends in common. A very nice guy. Quite different to when he was on stage. He was very humble. I was very fond of him.

On September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix passes away in his sleep – choking on his vomit after a combination of sleeping pills and red wine – at the Samarkand Hotel, Notting Hill. He was only 27 years old. Earlier in the evening he’d been at Ronnie Scott’s jamming with Eric Burdon, just like the old days…

Eric Burdon: Quitting my band War all ties in to Hendrix’s death. When we were on our way back from Paris, we passed through London and Ronnie Scott’s club. And that’s when Jimi died. That weekend, we were the last people he ever played with. It shook me up pretty bad. I went back to California for, I hoped, peace of mind. But it just got uglier and uglier. It was a pity to see a guy with whom I’d had lots of conversations about life and death end up like that. To see his body and the aftermath being tossed around like a basketball.

I remember having endless discussions with Hendrix and John Steel from The Animals. We were convinced we weren’t going to live that long. Maybe it’s the Jesus complex. I tried to quit music a few times [after Hendrix died], but I always came back. I mean, what are you gonna do? It’s too late to take up a profession in the medical world or be a bricklayer. That Jimi thing has never gone away. I just have to equate within myself that I was lucky to have been around at that point.

Ginger Baker: We became friends through Jimi’s chicks, really, but we were also getting something together musically in 1970 after Blind Faith ended. He came over to my house in Harrow-on-the-Hill for dinner and we spent the whole day together working on stuff and then within a week he was dead. It was terrible.

We were looking for him the night he died. Sly Stewart and the Family Stone were in town that evening and I’d got a big bottle, a marmalade jar size, full of cocaine hydrochloride, which a guy had nicked from a London hospital. Mitch saw the bottle and I told him there was another one going for 350 quid and Mitch went, “Oh man, Jimi will really go for that”. So we all went to look for him. I was with my wife and Mitch and Sly Stone, and we couldn’t find Jimi anywhere. We went to every possible haunt we could think of. We went to his flat, the Speakeasy, the Revolution and we just couldn’t find him.

Leslie West: I know exactly where I was when Jimi died. I was checking into the swanky Sheraton Cadillac in Detroit and when I signed in the lady says, “Another of you rock musicians died last night”. Who? “The guitar player. The black guy”. I said “Hendrix?”. What a fuckin’ waste…

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.