“This well-dressed man walked out on stage, reached inside of his jacket, pulled out a gun, and goes pop-pop-pop. I’m thinking: ‘Oh, I’m dead’”: The epic story of the rise, fall and resurrection of the original Alice Cooper band

The original Alice Cooper band have reunited for their first album in more than 50 years. This is how it happened

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

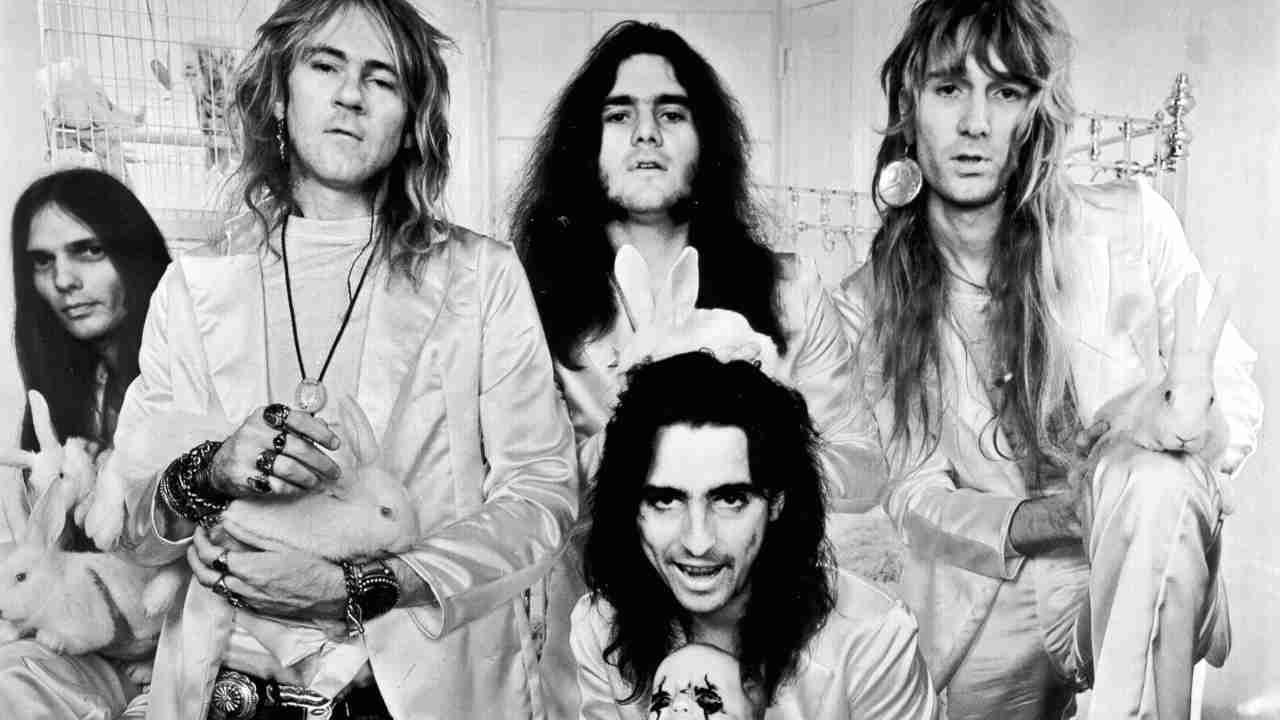

Eccentric performers and preternaturally talented showmen, the Alice Cooper band were as much art provocateurs as musicians, one of the few glam acts that managed to slither into the mainstream. It seemed barely more than a blink of a mascara’d eye that saw Vince Furnier – shortly to be rechristened Alice Cooper – Dennis Dunaway, Neal Smith, Glen Buxton and Michael Bruce going from being “the most hated band” in Los Angeles, with the superpower to clear a venue in a single song, to becoming one of the biggest bands in the world.

After the release of sixth album Billion Dollar Babies, in 1973, they were on top of rock’s mighty slag heap, with the album at No.1 in the UK and US and three top-10 singles in the UK in that year. Looking back over five decades with something of a jaundiced eye at some of the lesser metal, shock-rock and hair bands that have fallen by the wayside, it’s impossible to overemphasise the effects that the Alice Cooper band had on music, performance, attitude, social (ab)norms and the outcast teenage audience at large. This was the band that changed the landscape of art, respectability and stage wear with their transgressive songs, morality plays gone amok, onstage executions, boa constrictors and twisted humour.

“When we came on the scene, the world was looking for a villain,” Cooper said sanguinely at the time. “And we were it.” In fact, it’s often been said that this was the band that drove a stake through the heart of the peace-and-love generation that preceded them.

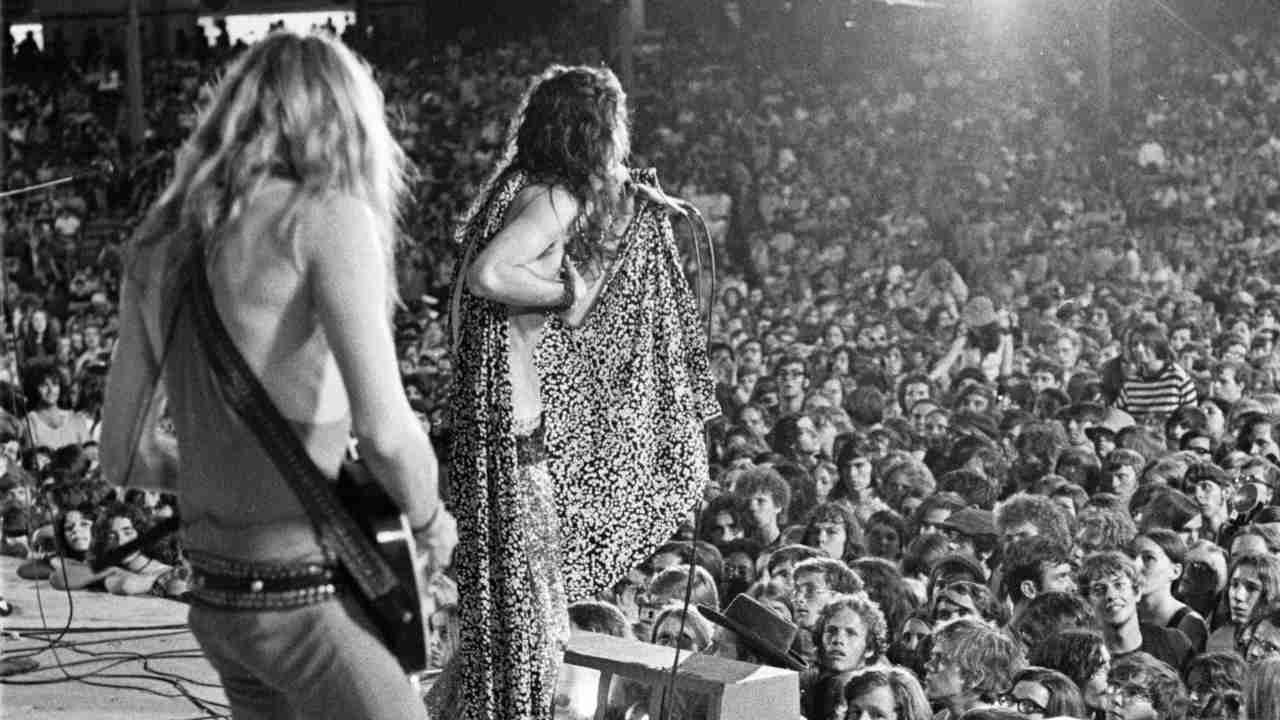

And they were about to do the same in South America. The first rock group ever to perform in Brazil, a Catholic and notoriously conservative country more accustomed to the samba, rock rural and Antonio Jobim records, the Coopers had come here two weeks before Easter in 1974 at the tail end of what they were still calling their Billion Dollar Babies tour. (The Muscle Of Love album was released in November 1973.) They were the number-one rock group in the world, according to a British poll, outselling David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Elton John and The Who that year. (Although a secret shame in South America was that they were runners-up to the Rolling Stones – not on the basis of sales, but because Mick Jagger was then married to a Nicaraguan woman.)

They landed in Brazil like conquerors on March 28, 1974. Not just a rock band, they were a menacing phenomenon, part circus, part horror movie, part phantasm, and all swagger, teenage-rebellion ritual, aggressive androgyny and psychic danger. In their satin stovepipe pants, messy black eyeliner and prodigious butt-skimming hair, the Alice Cooper Group didn’t just arrive, they invaded.

Their visit to the southern hemisphere was Beatlemania plugged into a different socket: one where The Beatles had been raised on acid, beer, B-movies and Detroit garage rock. From the moment they arrived they were flanked by bodyguards (Alice had seven of his own) and corralled into jeeps equipped with mounted 50-calibre machine guns, but the security couldn’t deter the fans. Thousands of them kept up 24-hour vigils outside the group’s hotel, trying to sneak into their rooms dressed as waiters, chambermaids and hookers. Many succeeded.

When group members emerged, despite the guards and guns they were manhandled, pushed and pursued, like a scene out of A Hard Day’s Nightmare. The first day, fans ripped the sleeve of Cooper’s jacket right off his shoulders, and grabbed handfuls of the band members’ hair as souvenirs.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The shows were even more frenetic and frightening than their arrival. Playing five dates over seven days, they set a record that endures to this day when they performed at the Anhembi Exhibition Hall in São Paulo in front of 158,000 unruly attendees. Undulating waves of aroused punters crashed toward the stage like an out-of-control soccer melee. “They looked like a field of wheat,” guitarist Glen Buxton drawled. “But a field of hair.”

“Yeah, those people looked like a wheat field flowing back and forth,” guitarist Michael Bruce echoed. “But I knew that if they flowed the wrong way, something bad would happen.”

Something did. When the band’s equipment was turned on, the crowd freaked out and began to stream forward.

“By the third song it looked like the ocean, because there were 150,000-something people in this humongous building,” remembered Bruce. “There weren’t any seats, and everybody was standing up, so as they’re pushing closer to the stage you get a wave effect happening. The wave kept crashing against the stage, and now you had bodies building up at the bottom. About the third song, the first person that climbed up on the bodies below them made it up on stage. And it was getting worse. I kept wondering what’s happening to the people on the bottom of this body bath.

“Then the next thing I saw was this well-dressed man in an Adidas top. He walked out on stage, reached inside of his jacket, pulled out a gun, and goes [makes gun noises] pop pop pop. I’m thinking: ‘Oh, I’m dead.’ We hunkered down, and everybody out of the audience went down [to the floor]. They ushered us off stage and we’re thinking: ‘What is fucking going on here?’ We’re all asking questions, but no one answered. Then after fifteen-to-twenty minutes they brought us back on stage. Everybody was sitting down now.”

The São Paulo show and the four after it were triumphs, the five band members playing as if it were the end of the world. Fans were half-convinced the devil himself had booked the amphitheater. More than half were convinced that Alice was the devil himself. They called him ‘the demon with a snake’. A newspaper ran a full-page photo of him on the front page with a single word beneath him: Macumbo! (voodoo).

But no one in the crowd that night had a clue that they were witnessing a funeral. On paper, the band were on top of the world. But beneath the glitter and the guillotines – and even the life-long friendships – something vital had unravelled. When they left the stage at Ginásio do Maracanãzinho in Rio de Janeiro on April 6, to the strains of School’s Out, their set closer, no one suspected – not even the band – that when they walked off that stage they were never to return.

Why didn’t they? Depends on who you ask.

It wasn’t until four decades later that their manager, Shep Gordon, in his 2016 memoir They Call Me Supermensch, broke the code of silence surrounding the days leading up to the break-up of the most beloved and, at one time, biggest group in the world.

Gordon wrote: “After the years of hard work and starving, the band was seemingly poised to take over the world. Instead, they were slowly falling apart. They scattered themselves around the Galesi mansion, where they were recording Billion Dollar Babies in Connecticut, and lived separate lives. Alice spent much of his time holed up in the master bedroom drinking Bud and watching TV, while the rest of them complained more about falling into his shadow. When we brought in a mobile unit to lay down the basic tracks for Billion Dollar Babies, [producer] Bob Ezrin also decided to bring in a session guitarist to play Glen’s parts.

“I understood why it upset the rest of the guys that Alice had become the star. They had all gotten into rock because they wanted to be stars. But they all couldn’t be the star. We had agreed that had to be Alice. We were on track to our goal of becoming millionaires. I couldn’t let their bruised egos derail us.”

Because of that, the blame is often laid at Alice Cooper’s platform boots. But the answer to the mystery isn’t as simple as that.

“I didn’t feel that something was changing after Brazil, that it signaled some kind of ending. Not at all,” Cooper says from a stop on his current tour with Judas Priest.

“Alice was pretty deep into the bottle back then,” reflected bassist Dennis Dunaway, “so he wasn’t always as available as he was in the earlier days. On the Billion Dollar Babies tour, Alice would be in his room with the bodyguards and they would have their own party going, and they wouldn’t want us to be there because it would be competition for them. And Alice would just be sitting there watching TV with a whole room full of people watching Alice watch TV. If Alice said can somebody get me a beer, a hundred people would scramble.

“But for me, no, the last shows in Brazil did not signify any kind of an end. I was always the crusader for forging on. Also, I was deeply convinced that Alice was my best friend, which he still is, and Shep Gordon was my best friend, and I’m the one that kept the pie-in-the-sky naiveté going.

“But regardless, it was certainly something, because after those five [Brazil] shows the band never played again.”

Was it just a case of a group at its peak crumbling under the weight of their success? They were more popular than they’d ever imagined, more famous than they’d ever dreamed, but also more fractured.

“People forget how dysfunctional we were,” Alice says simply today. “Especially when we were the hottest band in the world. We were voted number-one band in the world. I think the band believed that. We always came from ‘We’ve gotta prove ourselves.’ Nobody ever expected us to even make a second album,” he adds. “I think we got cocky. That wasn’t who we were. I don’t think the band remembers that.”

Oh, but they do.

“Did I know we were the biggest band in the world? Of course we did,” says drummer Neal Smith. “We had worked very hard to achieve what we had achieved at that time, and we were all enjoying it. People always ask if I could have anybody or anything. And I did, by the way. Was I an asshole about it? Yeah. But I was a happy asshole.”

“We believed from the very beginning that we were going to be a big band,” Dunaway remembers. “We couldn’t believe it that every time we put out an album the world didn’t see it the way we did. You can look at Neal, and think he’s got this rock-star personality going. He had that way back when he was playing clubs in Phoenix, Arizona. So it wasn’t like all of a sudden, we’re just a lowly band and overnight we’re big stars. We already thought we were stars. The difference was that the world finally believed us.”

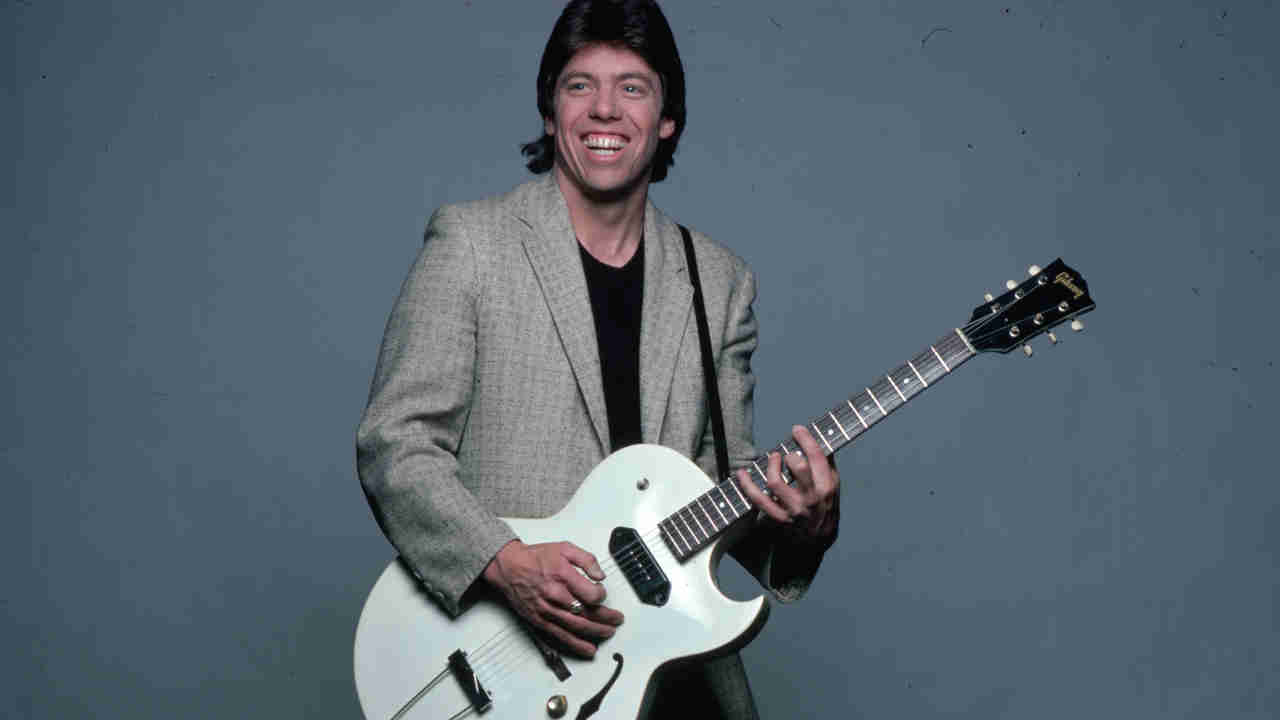

But Bruce never seemed to feel that way. A tireless songwriter, a little bit of an outsider in the group – a former football player, he went to a different high school in Phoenix than Dunaway, Cooper and Buxton – he looks at the past through a different lens than his compatriots.

“What was it like to be that famous?” he asks rhetorically. “I’m not sure I even know. I don’t think we expected Billion Dollar Babies to go to number one, first of all. We were gradually coming up in the trades, each album building on the next, and I think we thought it was going to keep doing that. It was like the first time we heard Eighteen on the radio. It was unexpected. We pulled the car over, pinched ourselves, and asked: ‘Is this really happening?’ Even after Billion Dollar Babies, I didn’t think it would go on for ever, because I felt there was a lot of work still to do. It was hard to keep it together, and it’s probably lucky it lasted as long as it did.”

Some say the break-up’s main cause was exhaustion: the slow poison of touring, recording and promotion without a break finally corroding the band’s centre. They’d been running on adrenaline and ambition for the past seven years, releasing seven albums during that time.

Others whisper that it was fame itself that killed them – that once they’d become the monster they’d created, they couldn’t outrun it. Or that Alice was getting all the attention. Had Buxton’s increasing drug use and withdrawal from the band destroyed the band’s delicate equilibrium, or was it Buxton’s resentment at feeling micro-managed by Bob Ezrin’s disciplined professionalism? Or was it principal songwriter Bruce feeling slighted that his songs were deemed not ‘Cooperian’ enough for their records, causing many to be shelved? Or that Alice and his then-girlfriend had moved out of the Galesi mansion for their own apartment in New York, separating from his pals for the first time since they left Phoenix in 1967?

So much more was afoot besides feeling that their pal Vince was getting all the attention. As with any break-up, you can never put the blame on just one single source, and the transmigration of Alice Cooper the band into Alice Cooper the man was no different. Separately, none of the causes seemed ruinous enough to derail this ground-breaking, chart-and-crowd-conquering band, but together they make a compelling case for what came next.

“There were just so many things that added up to that break-up– unconscious things, psychological things – and it really was that we gave it everything we had for seven years and we were tired,” Cooper sums up. “The thing that would bother me was that we were getting on each other’s nerves for the first time. We didn’t know how to stop it, and the only way we could stop was sort of a divorce for a while, or a separation.”

So they took a break. Bruce made plans to turn his collection of songs that didn’t fit the group into a solo album, which in turn prompted Neal Smith to announce his plans to record his own solo album. From the beginning, Dunaway was staunchly against the hiatus, writing in his memoir, Snakes, Guillotines, Electric Chairs: “I had some songs too, but they were all intended for the Alice Cooper group. If loyalty is a weakness, then I’m a wet noodle. Still, I fought tooth and nail against the idea of solo projects.” Buxton didn’t seem to care one way or another, and Cooper didn’t say a word about his plans, which at the time no one thought was odd. The five friends made a pact to return in a year’s time to record what was to be the group’s eighth album, come what may.

“We did everything by a vote; no one’s vote had more power than anyone else’s,” Dunaway explains. “Whatever the majority wanted to do, then we would go with that. When it came to Michael deciding he needed to record an album where he didn’t have to submit it to a band that was going to change ‘I love you’ to ‘I want to kick a puppy’, I was totally against it. In fact I was absolutely against taking any kind of break. I said: ‘We just made it to number one, are you kidding?’

“The argument that won me over was that Alice and Glen were in such bad shape that we needed to get them out of that situation so that they can get a chance to dry out. So we decided that we were going to take time off, Michael would record his album, and then the band will get back together, and after the break we would do a bigger album than ever and we’d be more popular than ever because of the break. That was what we thought was going to happen. In the time off, Neal did his Platinum God album. I helped him with it, but that was just so Neal and I could keep in shape so that we wouldn’t lose our chops.”

“For me it was more than keeping my chops up,” Smith said. “After we got back from South America, Michael wanted to do a solo album. We all agreed, so you can put blame on anybody that you want to, but we all agreed to take the year off and in that year we all agreed we could do a solo album. Glen didn’t want to and Dennis didn’t. But I did, and recorded Platinum God, and Dennis helped me on it. Michael did his album In My Own Way. Then, to our surprise, Alice did an album, Welcome To My Nightmare. We weren’t expecting that. I’m not sure why not.

“Usually we would have just talked everything,” Smith explains. “It was the first time that the band was ever separated. When we were together, we always talked about and resolved problems. Alice got a place in New York really close to Shep and we were still out in the country. We didn’t have much communication with him. In fact we didn’t find out until later Alice was doing Nightmare. He had as much right to do an album as we did. But we were still surprised.”

“I had the idea of Welcome to My Nightmare,” says Cooper. “I didn’t know where it was going to go, but it was a great title – a great Alice Cooper title. But I felt that the band was going to say: ‘Let’s not put all the money back into a show, [and] a bigger show than Billion Dollar Babies. It would be nice to actually have cash.’ Because we always worked that way. We always had whatever we needed, but nobody had a giant bank account. Because a lot of our cash went back into the show.

“I think being exhausted and taking no time off and going to a bigger project made a lot of people go: ‘No, wait, wait, wait. No.’ I was dumb enough to say let’s do it.”

And he did. But without the band.

“All five of us were together; we were returning back from something we did in New York,” recalls Bruce. “I think it might have been that meeting where we decided we’re going to take that year off, and we’re just coming back discussing the details. I remember we were talking about the Battle Axe idea that Neal and Dennis and I were kicking around, and Alice was telling me about a dream he had where he’s in a nightmare and all these things come to visit him, like the Cyclops. I told him that was kind of a neat idea, maybe we could pursue that after we do Battle Axe. Now I reflect on how egotistical of me to tell him we could think about it after Battle Axe, and not really listen to what he was saying. But the three of us – Neal, Dennis and I – were jamming on the idea of Battle Axe.”

Would further consideration of the Welcome To My Nightmare concept have changed things? Probably not.

“Our agreement was whether anybody or nobody recorded an album, we would get together a year later and record the next Alice Cooper album,” Smith reiterates. “You could tour, you could do concerts, play in clubs to support your album, that’s what we agreed to. So Alice had monster success with Welcome To My Nightmare, and wanted to do a second album, which was Go To Hell [Alice Cooper Goes To Hell]. I don’t know whether that was referring to what the rest of the band could do, but that’s another story.

But Alice reneged on the deal. “If I would’ve found success with Platinum God or if Michael would have found success with In My Own Way, would we have continued with the band at that point? Would we stay? I don’t know, because it never happened, but I’m just saying that was the risk, the gamble of any of us doing a solo album. It’s like Peter Frampton with Humble Pie. Are you going to be successful, or you put Humble Pie back together after Frampton Comes Alive? You don’t know until it happens, and then you go day by day. The inside circle story doesn’t matter, but the reality of it was Alice found success as a solo artist and for whatever reason didn’t come back to the band.”

The message was loud and clear when the band members found out that their friend had applied to legally change his name to Alice Cooper.

“People would come and see us play, and just assume that since I was the lead singer then I had to be Alice Cooper,” he explains today. “But originally the band was simply called the Alice Cooper Band, and because everyone thought I was Alice we all decided it would be easier and better for the band to start calling myself Alice. At one point Shep [Gordon, manager] goes: ‘Let’s just make sure that if you’re going to be Alice, if everything did fall apart you could go on with the name. So later, when I went solo for Welcome To My Nightmare, I’d really become Alice Cooper.”

You might think any group would think about legal action. But not this outfit. Which has everything to do with everything that has come after.

“The first thing Alice did was change his name legally,” Smith explains. “We all owned the name, but there was never going to be a lawsuit, because I would never sue my friends. That’s why we stayed friends. We worked out an agreement that would allow Alice taking the name and we would take Billion Dollar Babies, our biggest album, as the name of the band that Dennis and Michael and I put together. And we got to work recording it. It would’ve been our eighth studio album.”

“I’m sure that Michael and Neal came to the realisation that Alice wasn’t going to show up before I did, because I still had this faith in our friendship,” says Dunaway. “I didn’t even really believe that the band had broken up until I saw the Welcome To My Nightmare show at Madison Square Garden.”

After that, the bassist couldn’t ignore it any more. The newly dubbed Billion Dollar Babies began auditioning singers, but couldn’t find anyone who could even approach the dramatic, unhinged intensity of Cooper’s vocals, so it was decided Bruce should be the frontman. The three tapped Alice Cooper touring keyboard player Bob Dolin and guitarist Mike Marconi to fill out the line-up, but they couldn’t replace the rough magic of Buxton or the brilliance of Cooper with new players. Smith, Dunaway and Bruce each spent more than six figures on an elaborate stage show, but they played only four shows, resulting in each member taking a massive financial hit.

“That show we put together was supposed to be the next Alice Cooper album,” says Dunaway. “We built this gigantic stage that had this boxing ring that hydraulically came out from underneath the drum riser, and these posts with velvet ropes would slowly rise up and lock into place, and these two gladiators would have this big battle with a guitar that looked like an axe, and it was a great show. But unfortunately, because the Welcome To My Nightmare tour was being advertised with our music and with no sign of it being not the original group, we had a hard time getting any gigs, because people are saying: ‘The Alice Cooper group is touring now. Who are you guys?’”

After a while they weren’t completely sure themselves. Dunaway sank into a deep depression. “I spent quite a few years sitting in a dark room in a rocking chair, pouting, but I had Cindy [wife], who would just tell me: ‘Hey, come on, get it together.’ I also spent years being so disappointed in the record company just dropping us, and our management. We were all individually signed to Shep Gordon and Joe Greenberg to manage each of our personal careers, and I felt that’s not what was going on. Music, this thing that I loved so much, had turned into a sour note for me. If I went in to New York City I would hide in the darkest corner and hope that nobody would recognise me or call me up to sit in for a song or anything I just went into my basement studio and wrote songs and jammed with Glen Buxton and Neal Smith and our other musical friends, because all I wanted to do is get the love of music back.”

But did Dunaway ever ask his friend Alice about what happened? Did it even hurt their relationship?

“I had been talking to Alice all along off and on. It was sparse [in the beginning], but when I was in the hospital in 1997, Alice called and we had dinner a few times. Alice and [wife] Sheryl would come over with baby Calico, but we would never talk about the break-up. It was always very congenial. Even though Alice and I had some chances where we were in a room by ourselves, I never brought it up, because for one thing everybody that knows Alice well knows that no matter what you talk about, he’s really good at saying what you want to hear. And also, he’s so good at it that it seems heartfelt and genuine, and I think it is.

“I don’t think he was the one that got to decide whether or not the original band came back. I think there’s other factors.”

“I think the band ran its course,” Cooper said quietly. “I think the band surpassed anything we had ever expected. And it took a lot of work to get there. I think I knew it when we started doing Muscle Of Love and the band – it was not my vote – decided not to go with Bob Ezrin to produce. ‘What!’ I thought. We’d just had two number-one records in a row and the band decided: ‘Let’s try something else!’ [Which was Ezrin’s mentor, Jack Richardson, and Jack Douglas producing.] That was the beginning of it right there. Muscle Of Love was a good album, but it didn’t have a direction. The songs were great, the producers were great, everything was great, except it did not have the Alice Cooper signature; there was nothing dangerous about it.

“That element certainly came from Bob Ezrin, who was our George Martin. And the fact that all of a sudden we decided not to use Bob! Right after it happened, Bob walked me outside and told me: ‘I can’t do this album.’ I asked him why not. He said because they won’t listen to me. I said: ‘Bob, I can’t imagine making an album without you.’”

The first thing Alice did when he set out to record his solo album was to call Ezrin.

“I had taken a step, a very dangerous step, because someone like Mick Jagger [later] made solo records that didn’t sell. If you’re Mick Jagger and you break away from the band and make an album and it doesn’t work, what chance does Alice Cooper have? But I really did believe in this. I believed in Bob Ezrin. I believed in Shep, and we had an idea.”

Did you intend to go back to the band after you’d released Welcome To My Nightmare?

“I never expected the solo stuff that I did to do so well,” he says, not really answering the question. “But if I was going to have a solo career, I was never going to give up with it. I was going to keep doing it until people got it. And that’s what happened. That success took me even further away from the original band. I could not have done Welcome To My Nightmare with that band. Trash would not have existed with that band. From The Inside would not have existed with that band.

“If I would have gone back to the band, I think that we would have just started making albums that weren’t as good as the early ones. I felt that if this band would have stayed together after Muscle Of Love we never would have got back together [like we have now]. Because we would have kept making albums that weren’t as good as what we’d already done before, and there would be something there that was all wrong. I think we might not even have been friends if we would have kept making albums and touring together, because it would just have died. It was already dying, and I think maybe we cut it off before it totally died.”

Maybe they weren’t left for dead, but his band members were struggling after he left. They still received royalties, but by the mid-80s all four were facing financial uncertainty and had to start making plans about their financial futures.

“After a certain point I had to actually get a straight job. It wasn’t easy, especially when the only thing on your only resumé is ‘I was in the Alice Cooper group,’” says Dunaway. “I had health issues that caused me to need to get health insurance, which meant I had to get a job. And at that time in the eighties it was difficult for a musician to even get car insurance, because you were in a high-risk category. I finally got a job, and it was retail, of all things [managing three Captain Video stores in Stamford, Connecticut].”

“If I lived in any state except Connecticut, I could’ve lived off the royalties,” says Smith, “but in Connecticut I had to do something else in order to make ends meet.”

The drummer took a course in real estate as a lark, along with a woman he was seeing at the time whose mother owned a real-estate company. “The daughter was going to take the real-estate course to get a license. I decided to take the course too, took the tests and passed and got my Connecticut real-estate license. I had gone through that 10-year period between ’75 and ’85, and Dennis and I had a band called Flying Tigers. We played a lot of clubs in Connecticut and Massachusetts, even as far south as New Jersey. After that I’d pretty much had it with the music business. I wanted a totally different lifestyle. I made some pretty good money in the real-estate business in Connecticut and had my license all the way till 2015, four years after the Hall Of Fame.”

Michael Bruce’s post-band history is a little murkier. Dunaway explains that the guitarist was travelling a lot during those years, while Cooper says: “We lost Mike there for a while. We didn’t know where he was.” But in 1997, Q magazine reported he was working as a student-detention counsellor for the state of Arizona. “None of the kids could believe I was in the Alice Cooper band, but they could relate to me,” Bruce told Q, adding that he was keen to work with his old team. “We really should jam to see if there is any juice left.”

He wasn’t the only one who thought so. Alice’s mother did too.

“I remember around when Special Forces came out,” Bruce recalls. “My mom got a call from Mrs. Furnier, Alice’s mom. She said: ‘I would love for Alice and Michael to get back together and write some songs.’ It was just a call from mother to mother. They can cut through the bullshit. She’d seen Alice losing weight and maybe going in the wrong direction. My mom told me about it, and I said: ‘Mom, my phone, my door, my window is always open.’”

Even thought that was back in 1981, the windows stayed open. And eventually something came through.

In 1985, Cooper called up Dunaway and Smith during pre-production for Constrictor, looking for input, ideas, a flicker of the old spark.

“It all goes back to when Alice contacted me and Dennis to work on songs with [guitarist] Kane Roberts,” Smith says. “We’d spent ten years apart, really not seeing each other. But Dennis and I always left the door open. ‘If you need anything, anywhere on the planet, I’ll be there, just say where and when.’ That kind of friendship doesn’t go away. There was never any animosity.”

From there the band began drifting back into each other’s orbits. In 1998 they played together at the first Glen Buxton Memorial Weekend, honouring their bandmate, who’d died the year before. That same year, Smith and Bruce performed at the opening of Cooper’s sports bar, Cooperstown. In 1999, Bruce appeared on stage with Cooper in Atlantic City, playing Under My Wheels – the first original member to share a stage with Cooper since the group’s final shows in Brazil. Alice invited them to contribute songs to Welcome 2 My Nightmare in 2011. But the real spark came later that year at the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction. On that stage, the original band played together again not as an act of nostalgia, but as something unfinished.

In 2015 they did it again, to celebrate the publication of Dunaway’s memoir. Chris Penn, who owned Good Records in Dallas, held an event at his store to promote the book. The four members plugged in, along with Ryan Roxie, Cooper’s guitarist at the time, for a short set [later released as Live At The AstroTurf]. Then, Bruce, Dunaway and Smith travelled to the UK in November 2017 and joined Cooper for five dates in Leeds, Glasgow, Birmingham, Manchester and London, every step bringing them closer to what seemed like an inevitable next chapter.

So what took so long?

“Cindy [Smith, Neal’s sister, Dennis Dunaway’s wife] is the one who finally brought it up,” says Cooper. “Ten years ago she said to me: ‘Why don’t you just do an album with these guys?’ She’s the only one that felt like she could talk like that to me. I said: ‘Because it’s not the right time yet.’

“And it wasn’t. There’s no explaining it. There is a reason why you can do an album like this. Dennis still plays like Dennis, Neal still plays like Neal, Mike plays like Mike, I still sing the same way. And that should not happen. But it does. They’re still angry. I’m still angry. The best guy that ever did that was Pete Townshend. He’s eighty-something years old. I tell young bands: ‘You want to know what to do? Go see Pete Townshend. He’s still pissed off, his knuckles are still bleeding because he loves hitting that guitar so hard. He will not give up. And neither did we. I never ever thought of us stopping.”

“I think it all happened little by little,” says Dunaway. “We started doing more shows – the Christmas Pudding shows [at Cooperstown]. We were inducted into the Hall Of Fame. Chris Penn was a big factor. And then us recording songs on Alice’s solo album. So little by little everything really came back together. I like to think that my book, writing about the positive rather than the negative, had something to do with it. In 2021 I got a call from Bob and Alice and they go: ‘Den, we’re thinking about doing an album’. We were all excited about it. Neal was sending demos to me and we were trading demos. Michael, Neal and Alice were in Phoenix, so they flew me out – just the band without Bob. We went into the studio at the Solid Rock Teen Center [Cooper’s nonprofit organisation just to rehearse and basically just to be a band together again.

Did Cooper think this day would ever come?

“I never thought about it, even though Dennis and I stayed in touch with each other all the time,” he explains. “It all came together in an odd moment of me going to Bob Ezrin: ‘Bob, would you be interested in doing another album with the original guys?’ When the two of us started talking about it, we said this could go way left or it could go way south. But we decided we could give it a shot. Bob and I had been making records for fifty years since [the end of the band], and we have a way of communicating. We figure out where the songs want to go and we go there. That’s what makes really good records. We needed to leave in the craziness of what Dennis does and what Neal does and what Mike does. All that needs to be on the record. That’s what makes Alice Cooper Alice Cooper.”

According to Cooper, Glen Buxton plays the part of the ghost in the machine.

“There’s an invisible factor here that nobody talks about, and that is Glen Buxton. Even though he was not functional during the end of Billion Dollar Babies, we could not sound like Alice Cooper without him. There was nobody that played like him, he was irreplaceable. When we could not use him any more, that took a lot of wind out of the original sound of Alice Cooper.

“It’s really funny how people remember Glen,” Cooper continues. “Guitarists will tell me: ‘I learned how to play guitar listening to Glen Buxton.’ “The guy that actually played on this album, Gyasi Heus, that was why we got him. He told us: ‘I know all the Glen parts.’ And we went: ‘Who knows all of Glen’s parts? Are you kidding?’ As a guitarist, on top of it we had the luxury of using Robby Krieger [from The Doors]. We didn’t want to get too far away from the ‘Alice sound’, but on Black Mamba who else could play that? It’s about a snake. Who plays more like a snake than Robby Krieger [the guitarist on The Doors’ Crawling King Snake]?

“When we got into recording Revenge Of Alice Cooper, we had more songs than we could deal with – between Dennis and Neal they brought sixty songs between them,” Cooper enthuses. “Everybody was excited about it. This album feels like it should’ve been the album after Billion Dollar Babies, not Muscle Of Love.”

So will there be follow-up to Revenge? A ninth Alice Cooper Band record?

Cooper responds: “We did a gang sort of interview, and they asked: ‘Is this a one-off project?’ I went: ‘Who says it’s one-off? This album’s really good, why wouldn’t we do another one?’ I think I might have even shocked Neal, Dennis and Mike when I said that. I mean, the band is the band. They’ll always be my band. And I’ll always be their singer.

“The moment when we disbanded, I felt really alone,” adds Cooper. “These are three of the best friends I’ve ever had in my life. I’d never been without these guys. And it took a long time to really get comfortable playing with other musicians. We [the original Alice Cooper band] were always the band that was looked down on. I was never, ever considered a great singer. So I really had to grow up. I really had to learn how to jam with other musicians. All of a sudden people were regarding me as a singer, not just an actor. So while that was really something that was good for me, it wasn’t immediately comfortable. Nightmare did well, Hell did well, Trash did well, Detroit Stories went well. I had some really, really big albums. But you can’t ever sit back and disregard the original guys. To me I always felt like that band was still together, we just haven’t worked in a long time.”

And now they have. After 51 years, the Alice Cooper Group made another album.

Not because they had to. Because they could.

The Revenge Of Alice Cooper is out on July 25 via EarMusic and will be reviewed next issue.

One of the first women to work in rock journalism, Jaan Uhelszki got her start alongside Lester Bangs, Ben Edmonds and Dave Marsh — considered the “dream team” of rock writing at Creem Magazine in the mid-1970s. Currently an Editor at Large at Relix, Uhelszki has published articles in NME, Mojo, Rolling Stone, USA Today, Classic Rock, Uncut and the San Francisco Chronicle. Her awards include Online Journalist of the Year and the National Feature Writer Award from the Music Journalist’s Association, and three Deems Taylor Awards. She is listed in Flavorwire’s 33 Women Music Critics You Need to Read and holds the dubious honour of being the only rock journalist who has ever performed in full costume and makeup with Kiss.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.