California Dreaming: the wild and tragic story of Spirit

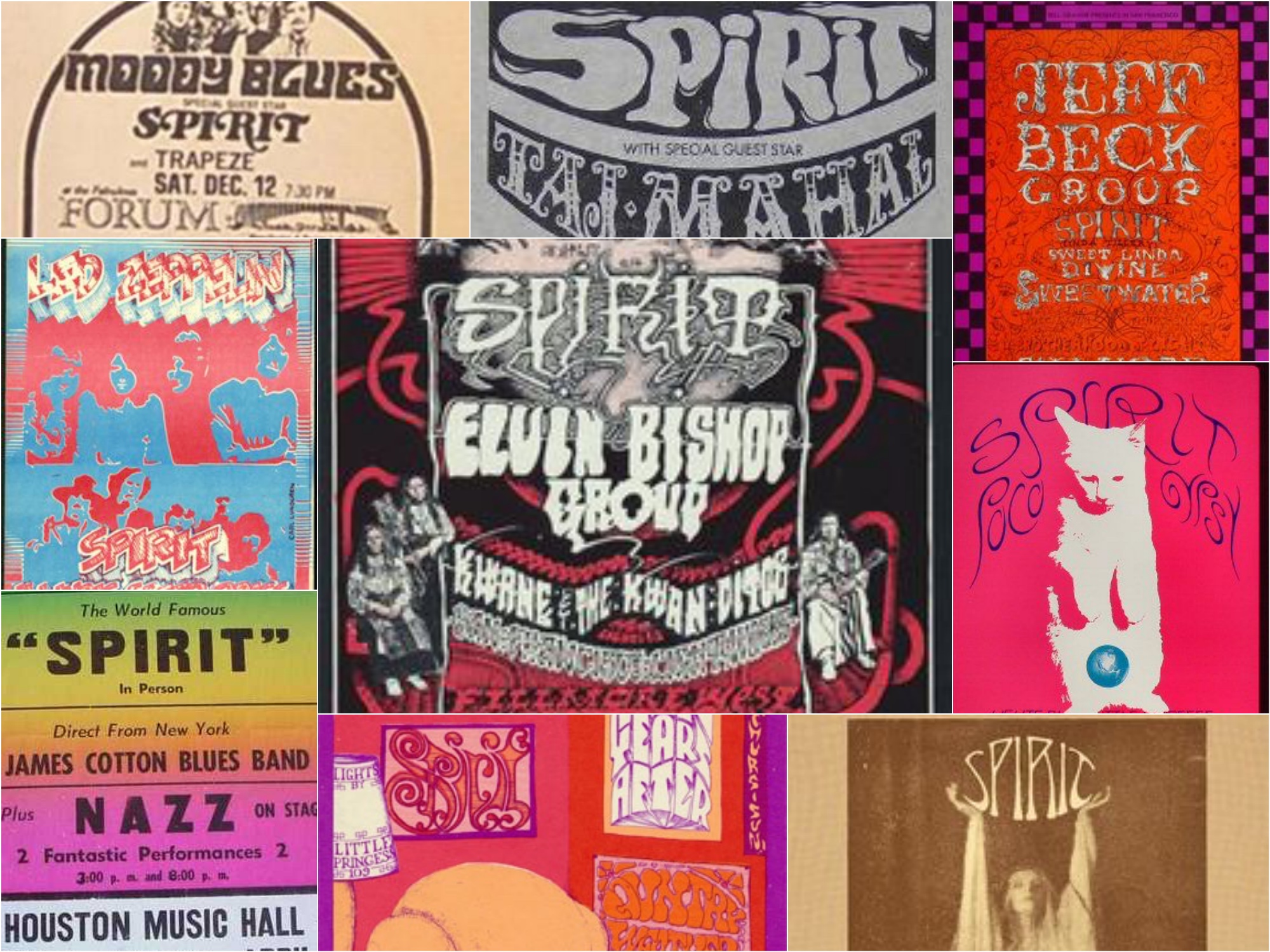

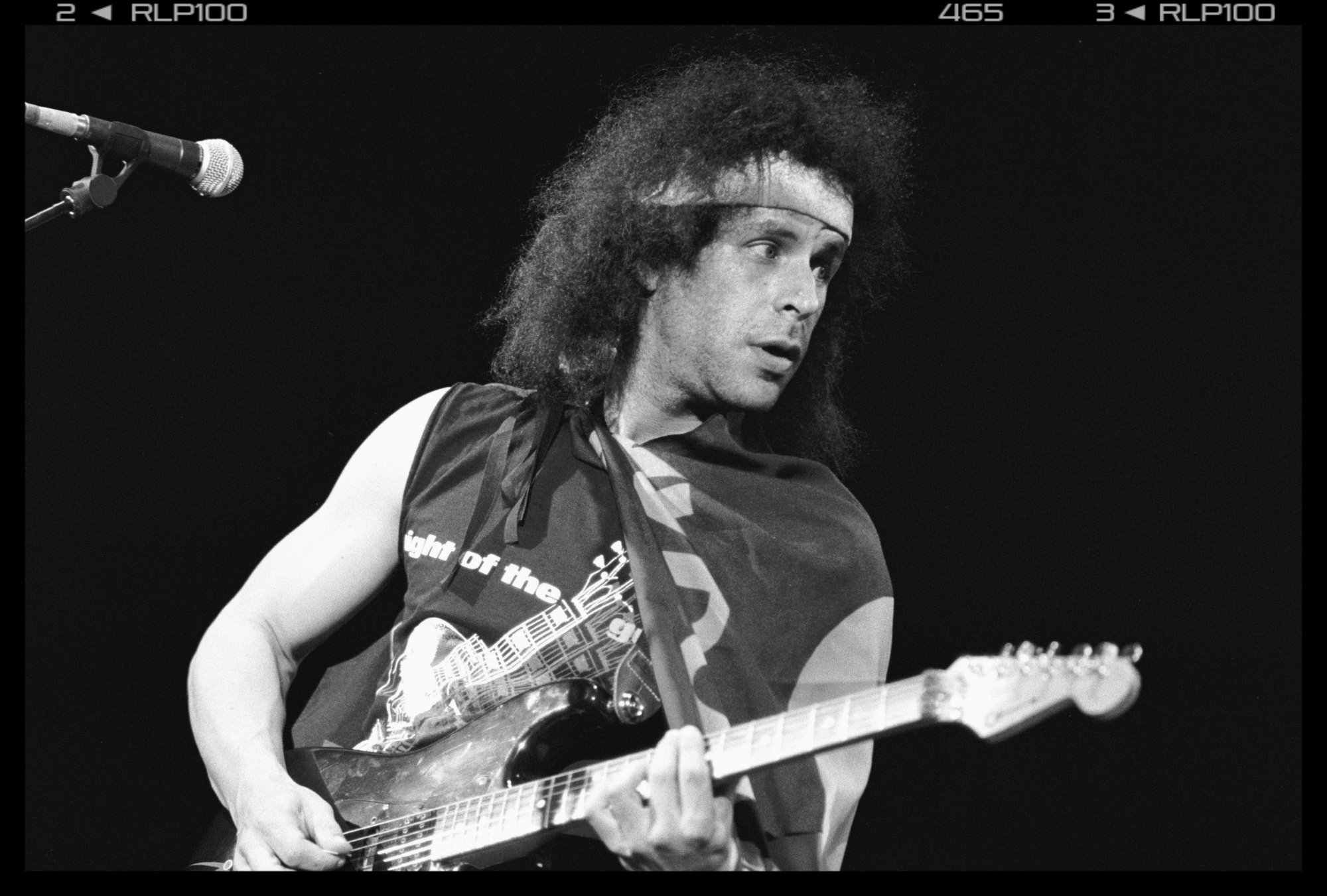

Led by mercurial guitarist Randy California, Spirit were buddies of Jimi Hendrix and praised by Led Zeppelin. But their promise would collapse in blur of drugs and death

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

London Bridge, mid-May 1973. Early morning. A tall, eccentric-looking man with wild Afro-Hebraic hair, wearing a kaftan and a turban, walks towards the riverside steps at Tooley Street and strips naked, as if preparing for a ritualistic dip in the Thames. Which would be foolhardy. The river is high, and while it looks benign from a distance, once you get close up the waters are angry and choppy and the currents are lethal, swirling around the footings of the brand new bridge that was opened just six weeks earlier.

Murmuring an incantation, the man looks skyward then dives into the filthy brown water. The man in question is American guitarist Randy California. He’s been tripping on LSD all night in the King’s Road flat, above a dress shop, that he shares with his fellow band members – stepfather drummer Ed Cassidy and bassist Larry ‘Fuzzy’ Knight – while the trio complete a European tour as Kapt. Kopter And The (Fabulous) Twirly Birds, aka Spirit.

Knight walked from Chelsea to the City with 22-year-old California that cold dawn. “He was in a bad place,” he recalls. “I don’t think he was trying to kill himself, because he was a great swimmer who loved the ocean. I said to him: ‘Are you sure about this?’ He replied: ‘It’s no problem.’”

A small crowd gathered as California breast-stroked out 10, 20, 30 yards. Eventually he turned, and made it back to the steps.

Twenty-four years later, swimming off the coast of the Hawaiian island of Molokai to celebrate the New Year, he didn’t make it out of the water alive.

Recalling that period, California told me in 1976: “If I hadn’t left London I’d be dead now for sure. I had to straighten out. Apart from being a church caretaker, I made charcoal and did some gardening. I grew pineapples and started to lead a happy, normal life.”

Fast-rewind to New York, June1966. Fifteen-year-old Randy Craig Wolfe is playing guitar with a black cat calling himself Jimmy James who is running a group, the Blue Flames, in local clubs. Jimmy (or James ‘Jimi’ Hendrix) spotted Wolfe by Manny’s Music Store and invited him to sit in with them at Café Wha? in Greenwich Village.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Manny Roth, who owned the café, told Jimmy: “This kid is dynamite. Give him a go.” During the next month, Wolfe blossoms in the band’s six-nights-a-week residency and is christened Randy California – to distinguish him from bass player Randy Palmer, who becomes Randy Texas. California shines on a repertoire including Hey Joe, Wild Thing, the beginnings of Look Over Yonder, Shotgun and Like A Rolling Stone.

One night at the Café Au Go Go, California starts playing slide using the neck of a sawn-off 7-Up bottle while James/Hendrix guns down a fat riff. Suddenly the kid reaches across to his boss’s guitar and spins the volume control down to zero. Hendrix throws a fit, flings his Stratocaster across the room and walks out on to the street. A tentative invitation from Jimi for the kid to join him on his maiden visit to London is withdrawn, and Randy resumes fitful studies in NYC before his mother Eunice Pearl and Cassidy whisk him and his sisters back to LA in January 1967.

The origins of Spirit date back to 1965 when Randy and Cass formed the Red Roosters with high-school friends Jay Ferguson and Mark Andes and Mike Fondiler at a music camp in the mountains outside LA. They played regularly at the Ash Grove, a folk and blues joint run on left-wing principles, owned by Ed Pearl, Randy’s uncle. The kid is so annoyingly precocious that he walks in to chat to the legendary bluesmen before their sets. He has to be hauled out by the ear one night when he discovers Lightnin’ Hopkins swigging a bottle of gin, with a couple of eager gals sucking on something else.

Back on the LA scene the Roosters became Western Union for a spell, but when Randy returned everyone noticed that playing with Jimmy James had altered his style; he wasn’t just playing Chuck Berry riffs. The old gang minus Fondiler reunited with Ed, adding his jazz pal John Locke.

Locke and Cassidy were two more reasons why Spirit were so fucking weird. Ed had a completely shaved head and wore all black. Born in 1923 he was already a veteran, having played with the likes of Gerry Mulligan, Cannonball Adderley and avant garde guru Roland Kirk. Ed’s mate Locke looked studious but was immersed in the West Coast acid culture. A friend of Doors guitarist Robby Krieger, he’d been living in a commune in Topanga. Eventually the hippies bummed him out so he told them to get lost and invited the group to move in. Calling themselves Spirits Rebellious, after a book of short stories written by Lebanese-American writer Kahlil Gibran, the group acquired a manager/mentor, Ann Applequist. Enamoured of Andes, she bought them studio time at the new Western Recorders, where the Beach Boys recorded Good Vibrations.

Locke’s rambling Topanga residence, known as the Yellow House, attracted a regular bunch of inquisitive visitors that summer of ’67, all drawn by the great rock-freak noise booming out of the open windows and thundering across the canyon. Confidante and equipment guru Barry Hansen (later known as the radio broadcaster Dr Demento) also lived in the Yellow House and produced the Spirits Rebellious’s first demo.

“One day,” he recalls, “we looked out and noticed just one listener, a man in his thirties, whose presence unnerved the group.” Dressed in filthy blue fatigues, with a manky beard, there was something strange about this chap. “Mark Andes said: ‘Ask him to please leave.’ I did as politely as I could, and he grudgingly started to move away. As he walked off he turned to me and shouted: ‘You’ve got bad karma, man!’”

Two years later Hansen recognised the man’s photo in a newspaper, which told of his arrest for masterminding a string of murders in the Canyon. “It was Charles Manson, the same guy who’d been hanging round Topanga in summer of ’67 and committed one murder there.”

The Applequist/Hansen demos were touted round Hollywood with no success, until Brian Berry heard them. He was doing A&R for manager Lou Adler, boss of recently formed Ode Records and an impresario of note. After auditioning for Adler at the Whisky A Go Go in Hollywood, Spirit signed – on the strength of Adler’s success with the Mamas And The Papas – and began recording in August 1967. But not everyone liked Adler, an old-school cigar chomper with a brusque manner.

Mark Andes: “Three of us were technically minors so our parents had to okay the contract. Adler was respected and ruthless but he didn’t nurture us. Our single Mechanical World was a regional hit despite minimal support. We signed the week before Adler organised the Monterey Pop Festival. He could have put us on. It was a missed opportunity because we were part of the thriving LA scene – we played a lot at the Ash Grove, the Golden Bear, the Kaleidoscope with The Byrds. We opened for Cream. Trouble was, our reputation as an idiosyncratic psychedelic jazz group meant we were influential rather than successful.”

“Lou was a strong personality, and on the first two albums I though he was fine,” Jay Ferguson says today. “Although when we heard our debut album and discovered he’d got Marty Paich to orchestrate the songs, fundamentally changing our sound, our jaws hit the floor.”

California was irate. “My problem wasn’t using Paich – who had worked with Frank Sinatra and Mel Tormé – but what happened to the overall sound. Paich didn’t come cheap, so we paid for that. Plus, Adler took the balls and guts out of what we’d done. I didn’t recognise half of it.”

In retrospect, Adler’s interference chimed with the ‘let’s add strings to the acid’ times. Love, who Spirit played with many times, had been ‘sophisticated’ by orchestration on Forever Changes; The Doors would soon pursue symphonic rock ground with The Soft Parade. Later, Randy took a pragmatic view. “We thought Adler would make us some bread. He didn’t, and instead he owned our publishing for five years and four albums.”

The self-titled Spirit, released in early 1968, was a hit of sorts in the US (Top 40 on the Billboard chart) and a cult favourite in Britain, much loved by Robert Plant who persuaded the emerging New Yardbirds/Led Zeppelin to cover its opening track, Fresh Garbage, in their live sets. Another song, Taurus, would feature in Zeppelin folklore, due to the similarity of its harmonic sequence to the future Stairway To Heaven. During the 70s, California might shrug and pass that off as one of those things. But by 1997 he’d changed his mind. “Well, if you listen to the two songs, you can make your own judgment. I’d say it was a rip-off. Maybe some day their conscience will make them do something about it. There are funny business dealings between record companies, managers, publishers and artists. But when artists do it to other artists… there’s no excuse for that. I’m mad!”

It’s a bone of contention that continues to this day, with Mark Andes having launched a legal bid to block the 2014 reissue of Led Zeppelin IV.

Spirit’s second album, The Family That Plays Together, produced a bona fide single hit in California’s I Got A Line On You (later covered by Blackfoot), but Andes accepts that Spirit were too strange for their own good. “We were so goofy we were doing John Coltrane tunes,” he says. “Fresh Garbage was influenced by Hugh Masekala [the trumpeter behind the riff on The Byrds’ So You Want To Be A Rock’N’Roll Star]. The Topanga Corral crowd loved us. Buffalo Springfield and Taj Mahal came to see us and we built a real buzz. Randy used to do an awful stand-up routine during the shows, telling really unfunny jokes. He was so gifted but quite immature, and the pressure on him to become the breadwinner was more than he could handle.”

The cracks began to show. Ferguson describes Spirit as “an underground thing where the centre could barely hold. Musically we were very good. We had a dramatic act. Randy was like the wizard, with lots of spacey effects at his feet. He dressed in furs and silks. Cass was impossible to ignore, shaved and dressed all in black. He had two field drums, like the ones used at football games, which he played with his bare hands. I had the Traffic look – very Anglophile with scarves and vintage jackets.

“Mark [Andes] was the good-looking one, and John Locke was like a mad professor in charge of the keys to the kingdom. We certainly didn’t dress down. But we seldom got further than middle-of-the-road money. We were never street-level savvy like the English groups. We met those people, The Move and Led Zeppelin, and they’d emerged from industrial towns and took no prisoners, whereas we were happy sitting on the beach. That’s the Californian disease.”

While recording the Family album, Spirit were asked to provide the soundtrack for French director Jacques Demy’s film Model Shop. Demy came to LA looking for a happening acid-rock group and chanced upon Spirit at the Whisky A Go Go. Demy’s wife, Belgian director Agnès Varda, had given her old man instructions to enlist The Doors, but Demy took a tab of sunshine with his driver and ended up in Topanga.

According to Ferguson: “Finding us was probably an accident. We were the first band Demy saw. But it was a culture shock for all of us. He didn’t speak English.”

Demy filmed Spirit in a seedy downtown studio, and Model Shop was actually a terrific evocation of the era, far superior to Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point. It was notable for starring Anouk Aimee and Gary Lockwood who was working simultaneously on another film, directed by Stanley Kubrick, playing astronaut Dr. Frank Poole in 2001: A Space Odyssey. (See the band in a clip here.)

As it was, Model Shop was a total flop and Spirit’s soundtrack was aborted for years, although they rescued parts of it for their fourth made-in-1968 album, Clear. Andes maintains that the Model Shop album “is really John Locke’s best work with Spirit. He was getting into John Cage and we flew off the walls.” Ferguson nabbed a cameo role in the film but found the experience “frustrating, as we played so well and nobody heard the results. Clear was a compromise, a collage of our work for Demy and new songs that didn’t quite hold together.”

Spirit were about to open the pod bay doors with their own spaced art-rock masterpiece Twelve Dreams Of Dr. Sardonicus. Yet having spent 1969 on the road promoting their opening trilogy of wonderment, they seemed to have missed the psychedelic bus. They played a few dates with Led Zeppelin at the turn of ’69 and made headway at the Atlanta Pop Festival, but after falling out with Adler they had no one to represent them when it came to appearing at Woodstock.

California was furious that they missed out again, blaming it on a rift between himself and Ferguson. “Jimi [Hendrix] instilled freedom and spontaneity in me – be loose and electric. But Jay always wanted tight, controlled sets. We were pitching for Woodstock, but since we couldn’t agree on anything it fell through. That was the beginning of the end for the original band.”

Still, Sardonicus really was something else. Adler’s departure persuaded California and Locke to get off their arses. They went to see Neil Young to ask his advice. “Try my guy, David Briggs,” Neil ventured. A stroll down Topanga Canyon found Briggs at home with his entourage of Valley chicks. After checking Epic’s advance, he agreed to slot Spirit into his production schedule while he was finishing Young’s After The Gold Rush album.

Briggs was quite a character. His studio catchphrase was: “Be great, man – or fuck off.” Andes describes him as “a gruff, tough guy with shades and a black hat who hung with a biker-type crowd. Randy loved him because he gave him room to express himself, but it felt like divide and conquer. Briggs was also the ‘sleep with your girlfriend’ type. We went on the road and he shagged my girlfriend. He was a complete rogue. I’m like, ‘The producer’s fucking my girl?’ Did it bother me? Yes it did!”

Andes couldn’t get a fix on Briggs. “He was unobtrusive in the studio, but he didn’t have any vision,” he says. “I thought he over-produced us. He had intuition, I guess. Now I agree – yeah, Sardonicus is Spirit’s masterwork. At the time, I didn’t.”

Briggs introduced Spirit to a show-business milieu – and a lot more hard drug use. Whereas before pot and LSD were taken for granted, now cocaine entered the room.

“We started hanging out with Neil Young a lot,” says Andes. “I used to drive round Hollywood smoking joints with him in his black Mini. During this time one of our dealer friends was shot dead after he fucked up on a financial transaction. Topanga started getting hard-edged. We were doing bottle caps full of blow but the creative juices were flowing. While we were mixing Sardonicus Randy fell off a horse and fractured his skull. During his recovery he was doing vast – and I mean vast – amounts of blow. Which was very unfortunate for everyone because he was never the same again.”

Sardonicus, released in late 1970, featured songs that would put the group at the forefront of conceptual psych-rock. The otherworldly atmosphere of the music was mirrored by trippy album artwork, created by mystic poet Ira Cohen at his Mylar Chamber studio in New York City.

“I saw that album as a quantum leap,” says Ferguson. “We made it at Studio B Sound City, and the talk was of making our own Ogdens’ Nut Gone Flake, or a Sgt. Pepper thing. Nobody else thought it that special. It got no airplay, terrible sales and shocking reviews, apart from in England where you thought it was the highlight of our career. That’s where it gained the reputation that eventually saw it go gold many years later. It was our pinnacle.”

In fact critic Nick Tosches gave Sardonicus a fair crack in Rolling Stone (“a blockbuster of a record”). Among the album’s many gems were California’s eco-epic Nature’s Way, Ferguson’s Mr Skin, and the stupendous Nothin’ To Hide where Randy lampooned the black magick crowd of Topanga weirdos in the lines ‘Swastika plug in your ear… jealous stars in your pants.’ Credit Briggs for suggesting they inject a drop-dead drawl ‘fuuaaack’ in the bridge. It’s total classic rock.

That album should have turned Spirit into stars themselves. “It was expensive enough,” laughs Ferguson . “A real Frankenstein thing. We had the ability to be like a Grateful Dead jamming group but I insisted on some structure. Randy blew up on that record as a writer. He was magnificent. It’s no wonder that we’ll always be known for Sardonicus, but we never made it to the Hall Of Fame. Since Cass died last year and John died in 2006 I’d love that to happen. Mark and me are the only two surviving members. That is chilling.”

At the height of their powers the original quintet imploded. Sick and unable to function, California began having visions. He cancelled a Japanese tour in 1970 and accused Andes and Ferguson of plotting against him. “Randy stopped acting rationally,” Andes says. “He wanted too much control of my life.” Following a near fist fight after their final gig, at Fillmore East in New York on January 30, 1970, Spirit slouched off in disarray – Andes and Ferguson quit and formed Jo Jo Gunne, California went into rehab. Having nothing better to do, Cassidy and Locke hooked up with the Staehely Brothers Al and Christian and recorded Feedback, again with Briggs.

Having tried unsuccessfully to kick his coke habit, California re-emerged in 1972 with the blueprint for his future career – the downright peculiar Kapt. Kopter And The (Fabulous) Twirly Birds solo album, which saw him reunited with Cass and a cast including Noel Redding (billed as Clit McTorius), his sisters Janet and Robin, and bassist Larry ‘Fuzzy’ Knight. Together they set about sifting over the debris of the guitarist’s on-hold Potatoland project, an Orwellian concept that produced the old Spirit’s swansong single 1984, while attempting a mash-up of tributes to Hendrix, The Beatles and Paul Simon.

In spring1973 the Kapt. Kopter band, now a trio of Randy, Larry and Cass, accepted an invitation to tour Europe, where demand for Sardonicus guaranteed kudos and ticket sales. According to Knight, “our agency said the import was top of the charts, so we left Topanga Canyon just after Randy’s divorce from his first wife and flew over. Randy was as weird as ever, if not more so. He was on a bulimia kick. We’d go out to eat good meals, then he’d rush back to our Chelsea flat and throw up. It was awful. The whole place smelt of vomit. It was all a big secret. We did The Old Grey Whistle Test. He took his shirt off in the performance and his ribs were sticking out. It was painful to witness.”

Knight watched California endure a protracted breakdown. “He’d be relaxed and open and talk about anything, or he’d become introverted and darkly brooding. He was stoned all the time. His cocaine usage was way out of hand and he was doing LSD. He lived in his own world but he had this obsession – he wanted the world to know that he was as good a guitarist as Hendrix – or better, or better than anybody else ever in rock’n’roll.”

California was a mass of contradictions. A supremely healthy jock, he was also embarking on a path to oblivion. “On that tour he deteriorated,” says Knight. “We played Finland, Denmark and Holland. And then we came back to London to headline at the Rainbow Theatre, and I saw him completely forget where he was or what he was doing. He blanked out. We did a twenty-minute drum and bass solo before his memory returned. When we finished, Cass and me went to the dressing room and he’d locked us out.

“Eventually he opened the door, and he was sitting there covered in blood. He’d taken a razor blade and carved words into his arm. He was so out of his body he was in an altered state, way out on the psychic edge. He said: ‘I always want it to sound like my guitar sounds to me on acid.’ It was more than crazy. He wouldn’t even listen to Cass; they had a bond, but who wants to hear what their dad says? That was a huge part of his problem – the father-figure thing. They respected and loved each other, but they’d grown apart.”

That London show triggered California’s dip in the Thames. “I was totally fucked up, my coherency gone. I’m a pretty far out person now,” he told me. “But I lived for the day then. We played the Rainbow and I was told we got seven encores. I don’t remember, I just remember the self-inflicted pain.”

Returning to the US, Randy booked into rehab. He didn’t pick up a guitar for two years as he tried to sublimate the ego problems leading him towards catastrophe. By 1975 he was living in Hawaii, working in McDonalds and also doing a stint in a rock mine. According to Knight, that was also a disaster. “He hurt his leg and it got so infected he was close to amputation.”

Finally shelving plans for the ill-fated and somewhat half-arsed Potatoland album, California embarked on a sequence of albums that cemented his reputation as one of the strangest dudes on the planet: the brilliant Spirit Of ’76, Son Of Spirit, the reunion Farther Along and Future Games – A Magical Kahauna Dream. During a concert at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, Neil Young had been invited to sing the encore, Like A Rolling Stone. But when he lurched drunkenly on stage California shoved him into the wings in front of an audience including many celebrities. A furious John Locke confronted California after and screamed: “I’m never gonna work with you again.”

Knight maintains that was “normal behaviour. Just before he got the Mercury deal for Spirit of ’76 Randy and me went to see Doors producer Paul Rothchild at his home in Laurel Canyon. Rothchild told us: ‘I can make you guys successful again.’ He asked Randy for his cassette, which was reluctantly handed over. While Paul sets up, Randy wanders round the house like he owns it then walks out the door into the woods for two hours. He was tripping. When he got back he picked up the tape and said to Rothchild: ‘I’m leaving now, your vibe isn’t right.’ That was typical. He hated the idea of being produced by anyone. His ego wouldn’t allow for that.”

Yet the man I met in 1976, though a space cadet of magnificent proportions, was a gentle and impressive individual who wouldn’t drink anything stronger than peach juice. “I can’t handle alcohol,” he said. “But I am addicted to tobacco.” He also admitted he still enjoyed LSD. Prone to non-violent mood swings, he was a manic-depressive but he was physically fit.

An attempt to revive the old Sprit occurred when they made The Thirteenth Dream in 1984. “It wasn’t satisfying,” recalls Ferguson. “We did the old songs, but without the old mood. There wasn’t much point to it.”

Randy California continued recording until his death, making a number of decent albums for various labels with minimal commercial success. He stayed in touch. In a late letter, he poured out his soul as usual and he’d drawn a few pictures in the margins – a guitar and a spaceship. What else? At the foot of the letter was the quote from Ecclesiastes: ‘To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heavens.’

On January 2, 1997 Randy drowned off the coast of Molokai. He’d been surfing with his 12-year old son Quinn when they were caught in a rip tide, which swept them from the shore. The coastguard rescued Quinn but as his father pushed him towards safety he didn’t save himself. The coastguard believed Randy let himself go. No one really knows. I imagine his death as simply being retrieved by a greater force. It’s nature’s way, after all. We’ll never see his like again.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.