“No debate, no coaxing, no schmoozing, nothing – I put music on the page and they play it. Don’t tell Sting!” Stewart Copeland on making music after The Police, being outdone by Pink Floyd, Curved Air, Neil Peart and life in his 70s

The accidental archivist revels in found sounds, movie soundtracks, spoken-word performances – and after dealing with his tensions of the 80s, explains why his brother isn’t talking to him

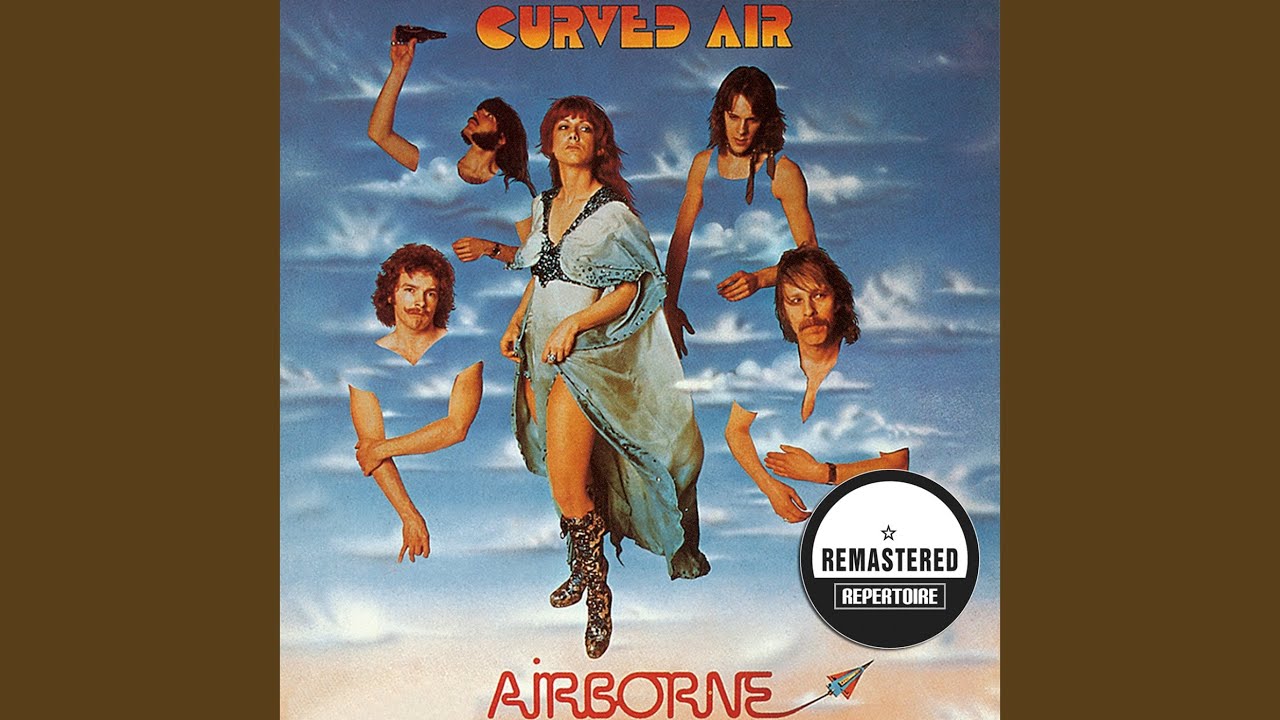

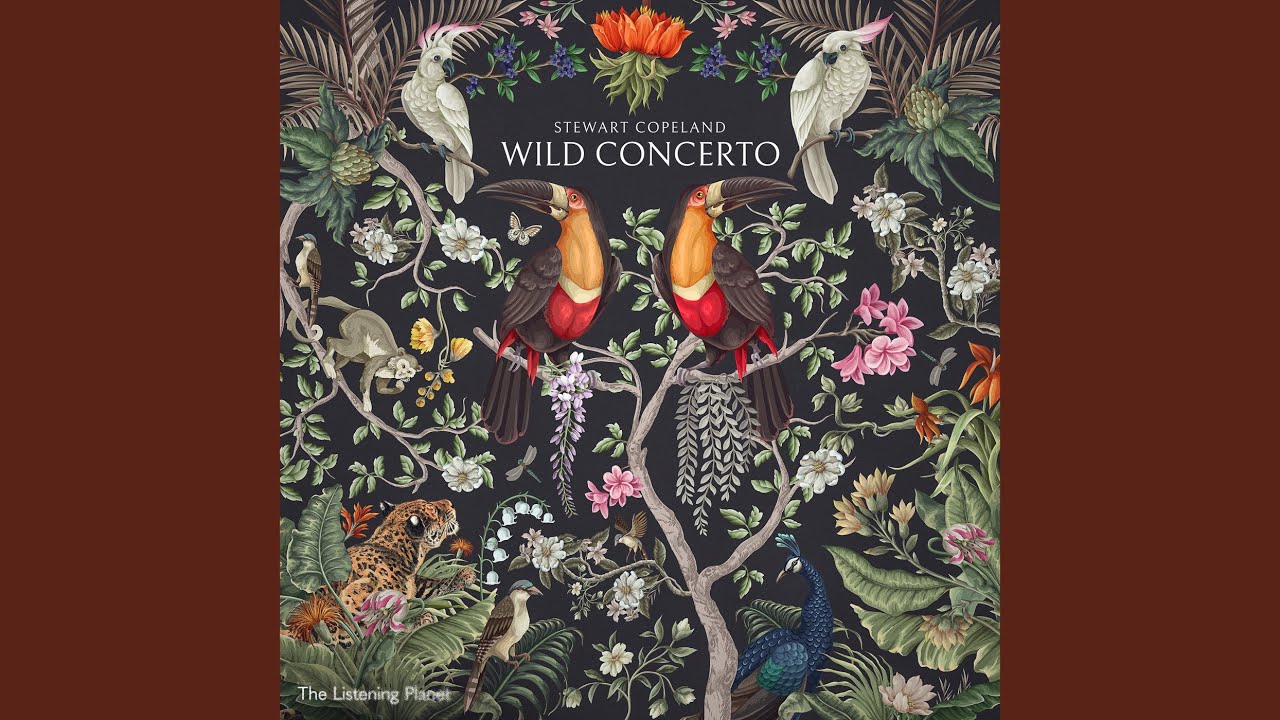

Long-limbed Police drummer Stewart Copeland has had a colourful life so far, taking in time with Curved Air and Gizmodrome as well as scoring movies for Francis Ford Coppola and Oliver Stone. He tells Prog about working with ‘The David Attenborough of sound’ on the nature-themed album Wild Concerto, his role as accidental Police archivist, his friendships with Neil Peart and Taylor Hawkins, and why he’s loving life in his 70s.

Stewart Copeland keeps moving. Professionally, creatively, behind his drum kit and, as it turns out, in interviews, too. Over an hour or so, as we chat via video-call, he does circuits of his expansive Sacred Grove home studio in Brentwood, Los Angeles, stopping only occasionally to flop down on the sofa. His flow of conversation only pauses when he thinks how to frame an answer or recall some minor historical detail. He’s a great advert for getting to 72.

We’re here to talk about his classical album, Wild Concerto, and a new Police photo book, The Police Lineup, due later this year, which charts the band’s earliest days living hand-to-mouth as squatters in London. However, both topics simply act as jumping-off points for conversational diversion: his one-man spoken-word shows, his time in Curved Air, his spirited leap from one of the biggest bands in the world to successful composer of anything from opera to acclaimed film scores (his debut score for Francis Ford Coppola’s Rumble Fish got him a Golden Globes nomination).

We also explore his friendship with both the Foo Fighters’ Taylor Hawkins and Rush’s Neil Peart, and why he and his brother still aren’t speaking.

Copeland, the son of a CIA operative, grew up in Virginia, Beirut, Cairo, and California; his childhood appears to have given him sea legs to adapt to almost anything and with some élan. Not least composing an album that fuses chirping Arctic terns and howling wolves with traditional instruments for the remarkable Wild Concerto.

You’ve teamed up with British naturalist Martyn Stewart and his hugely extensive archive of field recordings for the album. Where do you start with a project of that magnitude?

To be fair, Martyn did a lot of the culling of the herd, as it were. He has a lot of sounds that are ornithologically very important, but they’re not musical. I started by putting them into three broad categories. One is the background, the environment, the wash, the sound of the jungle at night, the sound of the wind sweeping across the tundra – that’s the atmos.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Then there’s the rhythmic elements, you know: [mimics a bird] ‘brip, brip, brip, brip’, there’s not much melodically there to work with, but there is rhythm. And then there’s the top line, the melodic birds, the red-breasted nuthatch, the sparrow and the albatross, even.

It’s not the first time you’ve worked with field recordings, is it?

I think perhaps one of the reasons why they called me for this project is because of my past working with found sound, going all the way back to the score for Rumble Fish: the street sounds, billiard balls, that sort of thing.

You did something similar for the Wall Street score, too?

True. I got the gig from Oliver Stone by telling him, “Music’s too good for these characters – let’s use dogs instead,” and his eyes lit up.

And your 1985 The Rhythmatist album was built on African field recordings.

I’ve been dealing with sound as a musical element for decades, which was what my trip to Africa was all about: to gather that stuff. In the early days it was actual physical tape loops going around the studio. I thought I was damn clever until I discovered recently that fucking Pink Floyd beat me to it by about 10 years!

Your 2006 band documentary, Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out is a remarkable record of the band’s arc, from small clubs to the US Festival, all shot on your Super 8 camera. Have you always been something of a collector/archivist?

I guess. I didn’t think about it at the time – you know, wasn’t everyone else keeping a diary, too? Anyhow, I was; I’ve still got them. [He opens two desk drawers filled with notebooks of all shapes and sizes.] These are from 76 and they’re tiny. I had notes where I wrote my secret innermost thoughts. You know, basically grievance nurturing, crackpot schemes, world conquest.

Andy’s the star of the film, because I’m not in it. Sting’s contribution is to just look handsome, which he achieved brilliantly

But the main diary was just how much we got paid, how many people showed up, and a rating for how we played. I was quite generous with my reviews. That was the genesis of the book [Stewart Copeland’s Police Diaries] and the film. It has the feel of a diary, capturing moments, squirrelling them away...

If I’d known anything about how you make a film, I would have maybe got some establishing shots: some cutaways, some reverse angles, perhaps. So, this was absolutely the home movie from hell. And you’ve got all this Super 8 footage; there’s no negative. Every time you look at it, you’re scratching it a little bit, and you can’t edit it without destroying it.

It all went into boxes, and I forgot about all that footage, about 30 hours’ worth. Then they invented computers and it became possible to digitise all that footage and start making a movie. I was just having fun with it, you know, pretty much for Sting and Andy Summers to enjoy. And a buddy of mine, Les Claypool, says, “Hey, you should send that to Sundance.”

I paid my 35 bucks, filled in the form and they accepted the movie. I went to Sundance and had a wild time there. In fact, Sting and Trudie Styler also had a film there that year [Styler co-produced the double award-winning drama A Guide To Recognising Your Saints]. Andy’s the ham, and kind of the star of the film, because I’m not in it; I’m behind the camera. He came out to Sundance too. Sting’s contribution to the film is to just look fucking handsome, which he achieved brilliantly.

Anyway, me and Andy are in the bar and Sting turns up. And there’s three blond heads in one place around the table. And somebody takes a picture, and the shot goes around the world. Next thing you know, Sting’s management’s calling up, saying, “How about we do our reunion tour?”

Curved Air was the most fun ever. The scene was dying at the time but we had a great ride for two years

That was the starting point for the band getting back together in 2007?

Yep, I don’t know about cause and effect, but there certainly is some synchronicity.

And you still talk? I imagine it’s like siblings.

Very much so; I’m speaking to my band members, at least. Miles, my brother [and former Police manager], is not speaking to me right now, though I’m happy to speak to him. He was pissed off that we didn’t hire him again, and that he wasn’t involved with the reunion tour. And my brother has an elephant’s memory.

You played with Curved Air for two years before you formed The Police.

I had the stacked boots, I had the long hair – In fact, I’ve got a whole bunch of shots of us playing at Cardiff Castle in 1976, Status Quo were headlining, and I’ve got these beautiful locks hanging down...

And you were married to singer Sonja Kristina too.

That’s how deeply prog I am! Honestly though, it was the most fun band ever. We were surrounded by a sense of entropy as far as the career of the band was concerned, because that scene was just dying at the time. But my mates in the band, we had a great ride for two years, and they were great musicians.

The Police Lineup book, with Lawrence Impey’s candid early shots of the band, captures that time post-Curved Air and the genesis of The Police very well.

Such a vibrant environment; and we were living in a squat in Mayfair at the time, which was within walking distance to the 100 Club, the Marquee, the Roxy. We were right in the thick of it. And it was a very exciting time in London.

Andy Summers has said Impey shot a bunch of unknowns like they were rock stars. How did you first meet him?

To go from The Police to working with Francis Ford Coppola was such a contrast. I remember thinking, ‘I want to do this for the rest of my life, not that’

At our boarding school, Millfield in Somerset. We weren’t in the same house – I think we met in English class. I was in the riding school at the time, which pretty much excludes all other school life because it’s so insular. But Lawrence had mentioned he was into Jimi Hendrix, and he was much more of a hobbyist than I was. He introduced me to Traffic, Emerson, Lake & Palmer; lots of things. We bonded over music at Millfield.

Later he shot us on the rooftop of the squat in Mayfair. We did some photos in Sting’s basement flat too – that was the day we’d fired [guitarist] Henry Padovani. We were very sad about Henry, but very excited about Andy.

You and Sting had pursued Andy like ardent lovers to join the band.

Ha! We were very much of the opinion that he was out of our league. We’d seen him play and there was no way he was going to team up with us; he was this triple-scale legend. We had nothing to offer him – we were dead in the water. Branded as fake punk carpetbaggers, we’re not going to get him. Sting and I are circling Andy, just plotting and scheming and having lurid dreams of having him in our band without any possibility of it coming to reality.

Until he told you he was joining the band.

Yeah, over coffee, out of the blue. Sits me down, and he says, “Stewart, you and that bass player, I think you’ve got something. But you need me in the band, and I accept!”

Was it a difficult transition from being in the biggest band in the world to scoring movies for Francis Ford Coppola?

Part of it was just getting out of The Police maelstrom – you know, the rat pit of The Police – over to San Rafael in Napa Valley where Francis was just so welcoming. It was just the most beautiful music experience.

This is 1983, just after you’d finished working on Synchronicity, recording in separate rooms, which producer Hugh Padgham said was for sound and “social reasons.”

The Rumble Fish score went down so well because I didn’t know how you’re supposed to do it. So it was revolutionary in a way

Yeah. Recording the album gets you the attention, but the recording process was hell on earth. The Police is like a Prada suit made out of razor blades. I’d gone from mixing at Le Studio in Montreal [aka Morin Heights] for those sessions. To go from that world to Napa Valley and working with Francis was such a contrast. I remember thinking, “God, I want to do this for the rest of my life, not that.”

Was the in-band fighting as turbulent as legend has it?

Well, not so much fist-fights – we had much more devastating psychological weapons. We knew where the short and curlies were and how to get to the pain point very quickly. We’ve had band therapy since, and we now understand what it was all about, and it’s all love and admiration and everything.

We’re all good, but at the time it was hell. I think it was like a bad relationship. You sort of get used to it, and you sort of think it’s normal; until you step outside of it and you go, “Oh, that’s not normal.”

You were nominated for a Grammy and a Golden Globe for your work on Rumble Fish. That’s quite the standing start.

I think the reason it went down so well is because I didn’t know how you’re supposed to do it. So it was revolutionary in a way. Plus, it’s quite an art movie. It was a very good confluence between Francis and me; we were both coming at it from, shall we say, unconventional viewpoints.

Was it a baptism of fire?

I was learning all the time. I’ll give you an example: I’d played Francis some of the score and he says, “This is really great, but it needs some more emotion. We need strings.” So, I call up the contractor, tell him the director wants strings. He goes, “How many?” And I didn’t know – “More than one, I guess.” So I get these players over, about 16 as it turns out, which is pretty intimidating. It’s not like hiring a session guitarist for the afternoon.

The most disappointing artists were the ones you’d think would be the most interested in the subject of what music is for

There are different tribes of musicians. In rock’n’roll we’re all musicians of the ear; we connect with the music with our ears and our eyes can be closed. These people – the orcs, as I lovingly and respectfully call them – they’re musicians of the eye. They read the music; and I didn’t have the technique to write anything fancy down.

I’m going through it with them, trying to make the whole thing sway to fit the scene: “She looks over her shoulder and I just need to feel love and care, you know, match the emotion of what she’s doing on the screen.” And instead of them looking all excited the way a guitarist would, they’re looking all anxious.

Finally, one of them says, “Maestro, do you want us to play what’s on the chart here, or whatever the fuck it is you’re talking about?” But they were so efficient – five minutes of music was done in five minutes. No debate, no coaxing, no persuasion, no schmoozing, nothing. I put it on the page and they play it. Don’t tell Sting…

That must have been quite the epiphany.

It was beautiful. And thus began my journey with the orchestra. I got better and better at it, doing more and more film. The good thing about film composing is that I’m a craftsman in the service of the director, who’s the artist. So, under the harsh yoke of cruel employment, I was forced to learn stuff that I never would have learned as an artist, such as writing a symphony.

Part of your new life beyond the drum kit also includes your one-man, spoken-word show, Have I Said Too Much? The Police, Hollywood And Other Adventures, and the excellent BBC series Stewart Copeland’s Adventures In Music.

I love the one-man show – I don’t have to rehearse for two and a half hours with an orchestra. I don’t need a shower after it because there’s no physical exertion. I show up in the afternoon, 90 minutes of blarney, get back in my car.

Neil saw his train coming and he had a first-class ticket, and he actually lived a year longer… Taylor was out of the blue

Okay, it’s so much easier, but not as thrilling. I got standing ovations and people laughed all the way through. And that’s when I was telling my sob story. I’m doing it again; I quite enjoyed the whole experience. Also, I can do four or five shows in a row; whereas when I’m banging shit, I’m good for two nights and then I need a night off.

Adventures In Music was so much fun to make. I talked to all the eggheads at Harvard and Princeton and Stanford and such, and they were amazing. Of all the artists I talked to, the most disappointing ones were the ones you’d think would be the most interested in the subject of what music is for. There was a lot of, “When I write a song...” And I’m like, “No, no – I’m not talking about your new fucking album!” They don’t think about what music is, why it affects humanity and why humanity rewards us so outrageously for it.

Talking of musicians who had a little more, you invited some of the great players to your Sacred Grove studio sessions, including two landmark but now lost drummers, Taylor Hawkins and Neil Peart. You played at the Wembley tribute show for Taylor.

Ah, yes, what a great day that was – but so happy-sad. Taylor was a close friend of mine, and he’s been over here at the Sacred Grove many times. I spent many hours agony-aunting for him. You know, I do that with all the musicians of that bandwidth. His relationship with Dave Grohl was really strong, but they did have issues. I would talk him down, having had experience with such issues myself.

As I got through my 60s and up to 70, I seemed to be enjoying every day more than the previous day

I remember I’d just come off stage in Nashville after a rip-snorting show. I’d headed down to the bar where there’s a wild party in progress. And just as I’m waiting for the elevator, I get the message that Taylor had gone. I couldn’t believe it. I still choke up when I think of good old Taylor. Way too young.

Then Neil, my good buddy Neil, also came over here a lot. Neil saw his train coming and he had a first-class ticket, and he actually lived a year longer than expected, but Taylor was out of the blue.

How’s 73 treating you? How is it being in your third act, as it were?

Life gets better and better and better. At 60 I got over the fact that things were beginning to fall off and malfunction. But then as I got through my 60s and up to 70, I seemed to be enjoying every day more than the previous day. Physically there are issues, but spiritually and mentally I’m having a great time.

During the height of The Police, when I was at the height of my virility, physique, and everything, I was anxious a lot of the time. Social vertigo, I guess. The stakes were so high and I was part of a machine. I remember it was a thrilling dream being realised – yet I was strangely anxious trying to keep that balancing act going. I don’t think like that any more.

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.