“They played us The Things We Do For Love. We thought it was beige. They said, ‘We need a weird one, a slushy one and humour.’ I said, ‘We don’t work to order’”: How Godley and Creme quit 10cc and went to play with their Gizmotron instead

Kevin Godley on the machine they invented at the wrong time, an overheard conversation, the decision that ended the band, missing the punk explosion, discovering video – and being mistaken for the drummer in Paper Lace

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

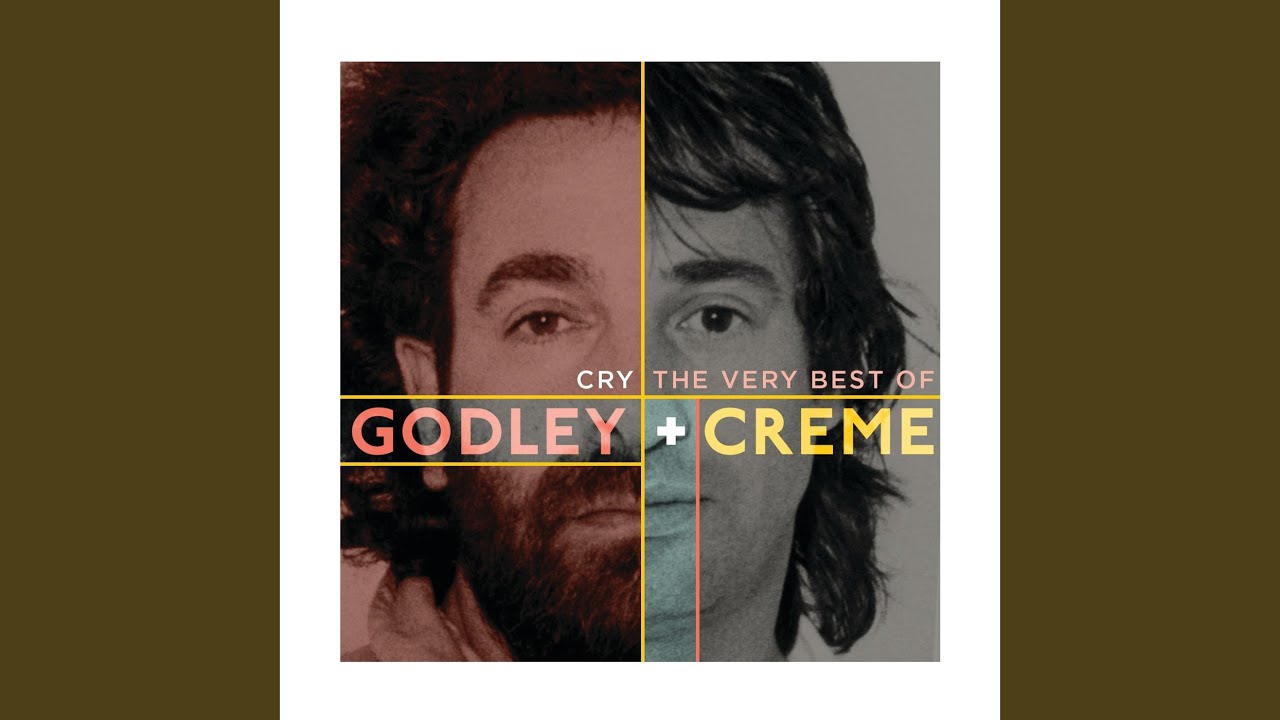

Singer-songwriter, drummer and Gizmo co-inventor Kevin Godley met his soon-to-be creative partner Lol Creme at art school in the 60s. They played in numerous bands together, including Hotlegs, which eventually became 10cc. They left in 1977, became Godley & Creme, and were soon elevated from pop stars to in-demand pop video directors.

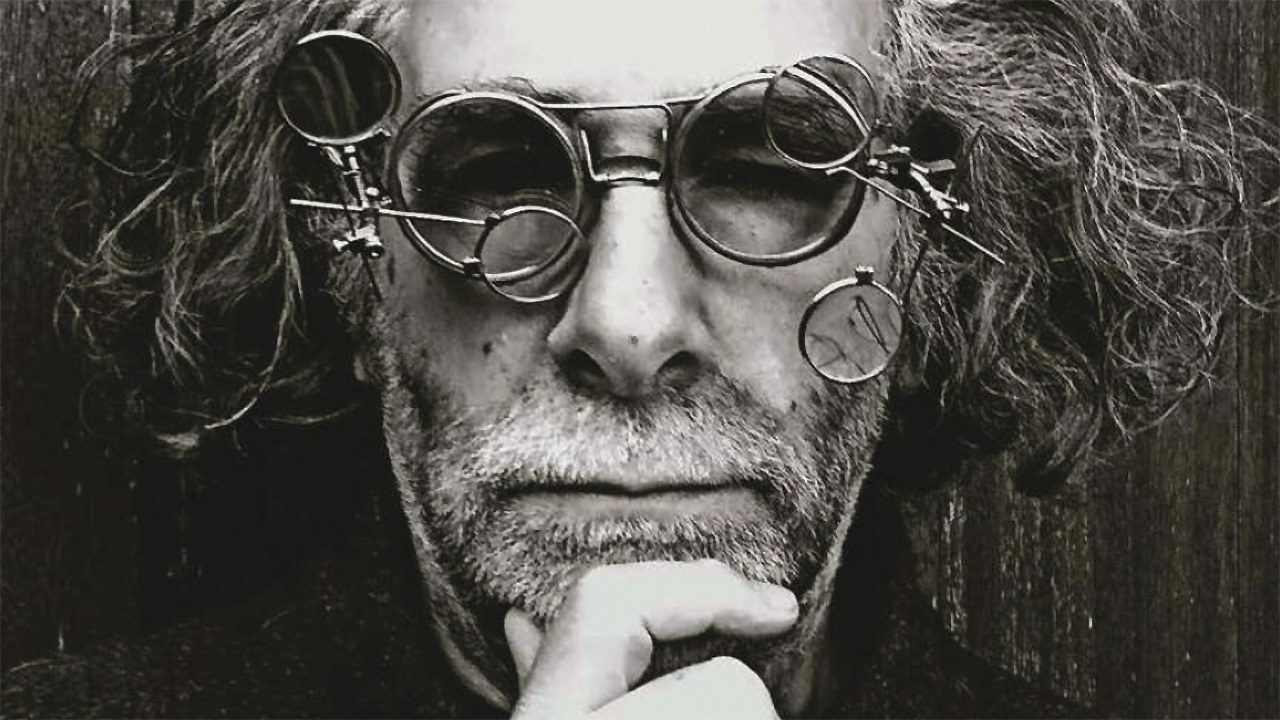

Godley tells Prog about the, ahem, consequences of the duo’s creative career, the recently released 11-CD set Parts Of The Process – The Complete Godley & Creme, and that time he was mistaken for Paper Lace’s drummer.

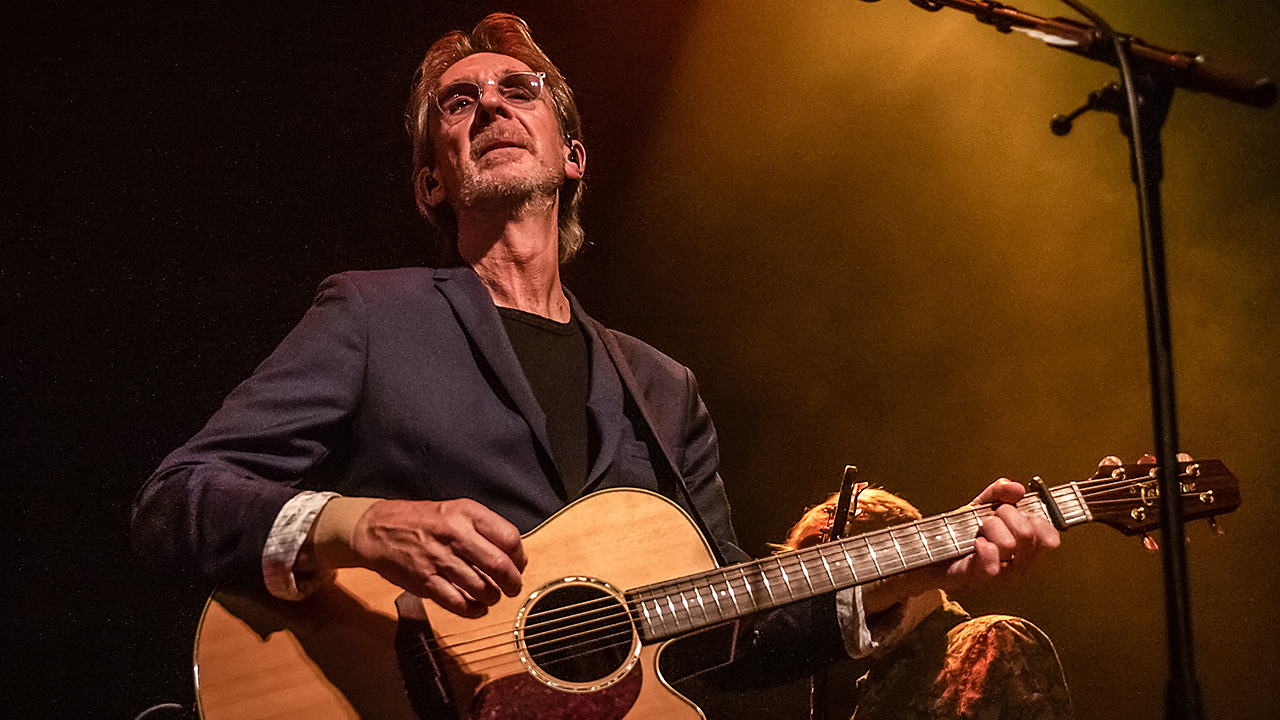

Art-school alumni, one-time prog pop star, songwriter, video and filmmaker, environmentalist: Kevin Godley has, for decades, confounded expectations in pursuit of what might be called his vision – though he’d probably baulk at the idea of being a visionary. At 79, he shows no signs of slowing down; he’s just completed work on an orchestral piece with American classical composer John Califra entitled America WTF? “It’s about the current political situation and divide in America,” he says. “It’s very dark.”

He’s also busy working on a musical, trying to finance two screenplays (both of which he had a hand in), and joining a video games company. “I’m not one of those people that will retire to the country and paint. I’m not that guy.”

We’re here to talk about the expansive new box set navigating Godley’s musical collaboration with former longtime writing partner Lol Creme. Parts Of The Process charts their musical arc post-10cc from the great triple disc/musical folly (argue among yourselves) Consequences – a concept piece that’s as much about divorce as it is meteorological disaster – to their final glimmering pop farewell, 1988’s Goodbye Blue Sky. However, our conversation touches on everything from his former band and writing with comedy giant Peter Cook to helping to pioneer the music video revolution and almost working with Bob Dylan.

Consequences reminds us of Zappa’s Jazz From Hell album. He was in thrall to making music with the Synclavier, while on Consequences you and Lol were intent on using the Gizmotron (Gizmo) device you invented. Would that be close to the truth?

Yes, we didn’t really get to use it very often in the context of the band. It just didn’t sit for whatever reason. We’d used it on one or two tracks. We kind of created this thing, conceived this thing and we thought, “Shit, what are we going to do with it?” I mean, we didn’t even know what it was capable of.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Not many musicians invent a piece of machinery in their downtime, let alone a Gizmo.

It was an actual piece of machinery, true. We’d always wanted to work with an orchestra in some capacity. But to actually do that you have to jump through a bunch of hoops, and they’re not cheap and they break for tea – stuff like that. There were Mellotrons around but we didn’t love them, and they kept breaking down.

On a good day the Gizmo sounded like an orchestra, and on a bad day it sounded like a chainsaw

We were looking at the guitar thinking, “This is a stringed instrument; why can it not be bowed in some way?” So, we sort of gaffer-taped Lol’s Stratocaster to the wall and. put an eraser on the end of an electric drill and held it against the guitar strings. A bit of a Leatherface vibe to it: it nearly sawed the thing in half! But for about four seconds there was a sound that was vaguely reminiscent of a violin. And we thought, “Ooh!”

So you made and marketed them.

Yep – John McConnell from the Manchester College of Science and Technology helped us develop the prototype. It was this bunch of wheels, sort of Da Vinci-ish, though not quite up there with the helicopter. It was John’s prototype that we made Consequences with. Then they were mass produced in the US by a company called Musitronics – but the timing was atrocious. It was the beginning of cheap synths, and it was very vulnerable to weather change and stuff like that. On a good day it sounded like an orchestra, and on a bad day it sounded like a chainsaw.

In 1976 – post How Dare You! – you and Lol took the Gizmo into 10cc’s Strawberry Studios to start work on Consequences. Were you still in 10cc at this point?

Yeah; it was the end of the album cycle and tour, but we were still in the band. We had some downtime – three weeks in Strawberry, as I recall – and the potential of working the Gizmo got us excited again.

Weren’t you excited by 10cc any more?

The problem with being in any band is everything becomes rote after a while. You lose the spark; it’s like, ‘Oh God, there’s another tour coming, there’s another album coming. We’ve got to write another bunch of songs.’ We were looking for something fresh. Our attention span was very short.

You were smoking your own body weight in dope and recording through the night. What was your mindset like at the time?

The label thought, ’We better get a responsible adult in to tame them.’ And the responsible adult was Peter Cook!

I suppose it was like – not a vanity project exactly, but something to test the capabilities of what we’d done. But there was no master plan. The first week or so was, “Let’s plug it in and see what comes out,” because we’d never really used it other than on Old Wild Men [from Sheet Music]. At one point, we created a tape loop – Phil Manzanera’s idea, as I recall. We put a bump in the tape and it sounded like a soprano opera singer. That was a revelation. But mainly, it was fun again. Then, as you know, it turned into a monster.

When did you both decide that you’d had enough of 10cc?

It wasn’t really one moment. There were a few meetings had because the label had been in touch. “It’s time for you to make a new album, boys.” Eric Stewart and Graham Gouldman had started writing songs for it. And we just didn’t have a taste for it. We were too into this.

They played us something – it might have been The Things We Do For Love – and we just thought it was beige. We’d had this pre-production meeting about the next album, and it went something like, “We need one of your long, weird ones, a slushy one, and we need some humour.” I was, like, “Hang on a minute – we don’t work to order.”

Prior to that, it was all about spending a certain amount of time in the studio and doing what we were capable of doing. We’d been relatively successful by going in the opposite direction. That’s what I enjoyed more than anything else. It was becoming a day job: we were taking care of business, but we didn’t take care of each other. We might have gone away and decided to come back if we’d had the time to stretch out and do what we wanted for a while, but that wasn’t allowed to happen. Four blokes. Four albums. Four years. That was it.”

Going back to Consequences, you and Lol decamped to the residential Manor Studios for three months, with Peter Cook in tow to continue with the recording sessions. Of all the people...

I don’t think he was there for the full three, but we had a lot of fun. I have this suspicion that by then the record label was thinking, “What the hell are these two idiots up to? We’ve agreed to release a record, but they’re spending more than the value of our country on this project. So, we better get a responsible adult in to tame them.” And the responsible adult they chose was Peter Cook!

They didn’t know there was a live mic open. We heard: ’What the fuck was that?’ ’No fucking clue. Are we going to sell that?’

It was a fascinating time. There were maybe two or three hours in the day where we were in sync. We worked at night and Peter, obviously, worked in the day. His concept was the divorced couple in the story; we’d provide the music and react to what the other was doing, but we’d rise at lunchtime, and we’d have a few hours together before Peter would start drinking. We were enjoying every second – that’s not to say we had a clue about what we were doing.

And there was no outside influence or producer to help guide you, tap on the studio glass and ask what the hell you were doing?

We were those producers! I remember there was an instance very early on when we were still at Strawberry. The managers of 10cc at the time came to hear what we were up to, so we played them the first 15 minutes that we had. We left them to it and they were saying all the right things – “Wow, extraordinary, amazing!”

We went out to have a cigarette, and they carried on talking in the studio, but what they didn’t know was that there was a live mic open. And we heard: “What the fuck was that?” “No fucking clue. Are we going to sell that?” The complete opposite reaction – but very managerial!

Among the dialogue and storytelling tangents, there are songs like Five O’ Clock In The Morning, which would have fitted perfectly on any of the first four 10cc records.

It was part of who we were; it’s in our DNA, so when we decided to write some actual songs, it sounded like us.

That album and a lot of your 10cc work is very visual. Is that a part of how you’re built too?

I think everything we ever wrote was visual. The only tools we had were audio tools; we didn’t mix with film people. We didn’t have a way into film, but we were art school trained. So there was always something bubbling underneath, but we did it in sound. I think we even called Consequences an “ear movie” at the time.

We’d become audio hermits. We weren’t aware of what was stirring: punk rock, the Sex Pistols, the polar opposite of what we were doing

I remember going outside to record windscreen wipers on the car in the rain – I forget for which song, but we were dedicated to getting it right. I’m in my car and the windscreen wipers were going, and it’s pissing rain and we had this mic outside. And there’s the guy on the pavement just looking at me, and it’s night time, and eventually he plucks up the courage and taps on my window. I wind it down and he leans in and goes: “Excuse me, are you the drummer from Paper Lace?” We got that on tape!

Lol says you were personally heartbroken when the album died a commercial death. Is heartbroken too big a word?

No – I was, because something happened to me maybe about three-quarters of the way through making it. I was very aware that we’d become audio hermits. We weren’t remotely aware of the outside world, what was stirring: punk rock, the Sex Pistols, the exact polar opposite of what we were doing. And when things like that happen, you must be aware of them. You can’t just keep going blindly and deathly forward, because it doesn’t really make sense.

I learned a lesson from that, but we were too far into it to start from scratch – forget about it. Then we heard they were going to release it as a three-album box set, selling for the extortionate amount of £12 quid in 1977 [approximately £70 today]. It was so ill-conceived; it did us a huge amount of damage. It fucked us up. We both put a huge amount of work into it, and no one liked it. No one understood it , and that ain’t going to help a career. It got slated in the press. We were the audio version of the movie Heaven’s Gate.

Did it really cost a million pounds in today’s money?

I don’t know how much it cost. It couldn’t have been cheap. Everyone was in and there was no way out. Peter Cook – even just that cost them a pretty penny. That’s for damn sure.

Remarkably, a mere two years later, the label fronted you cash again for something that couldn’t be quantified at the time: a music video.

I know; we weren’t a touring band. We had a single coming out, we were always a bit of an anomaly for the label. They didn’t quite know what to do with us, particularly after Consequences. The album was Freeze Frame and the lead single was Englishman In New York, and we thought the only way to get seen or heard was to do a short film or something. So we came up with a storyboard and the label loved it. We didn’t know there was going to be such a thing as the video industry or indeed videos. Nobody did then.

They got us a director called Derek Burbidge [The Police, AC/DC] and his job was to make our vision, such as it was, come to life – which he did, admirably, and during that one day of shooting and the subsequent day of editing, a huge light bulb switched on above our heads. We thought, “Fuck, this is brilliant – we could do this!” I even liked being out front in my red shirt and my swish suit, Mr Cool. When I looked at myself I thought, “Fuck off!” but at least I was trying.

Then in 1980, Steve Strange and Visage approached you about making something for them for their Fade To Grey single.

Yeah, our albums were slowly ticking over, but we still weren’t touring; we weren’t doing anything. They wanted a video because they couldn’t get on Top Of The Pops or Whistle Test, so they made a film as a stopgap. People would play the film and liked what they were seeing, but there was no infrastructure in place; no video commissioners.

It was all word-of-mouth, musician to musician – a trust thing. So we were lucky. We were at the beginning of something; we’d never been in that place before. We filmed it, helped do the edit, learning all the time. Then we began to be the go-to people for a while. We had this reputation. And we got to do some really interesting things.

You must have had so much creative energy at that point. You did more than 50 music videos in the 80s for The Police, Duran Duran, George Harrison Lou Reed and others, and yet you were still making music.

Orson Welles was asked about how he’d made Citizen Kane. He said one of the most important ingredients was ignorance

I remember us putting out Under Your Thumb [from 1981’s Ismism], and we didn’t have any hope for it at all as a single. And we were shooting a video for Toyah Willcox [Thunder In The Mountains] on an airfield somewhere. A production guy came running up and said the single had just gone in the top 50. I was like, “Hang on a minute – how do we deploy the two things that we do?” But it was the same stuff. It just came out of two different taps. We turn this one on when we’re doing film. We turn this one on when we’re doing audio. It was just a natural thing, and those two things had somehow matured together.

You ended your creative partnership with Lol after arguably one of the best albums of your career, 1988’s Goodbye Blue Sky – which earned you an unlikely fan.

Dave Stewart got my wife and I in to see Bob Dylan at Hammersmith Apollo and we got to stand backstage and watch him. At the end of part one, after wowing everyone with Maggie’s Farm or something, he walked straight up to me and said, “You still making videos? Want to make one for me?” And then walked off. We met him at a hotel a few days later and he said, “You did a video where people were going through each other. Coming forward and going back,” and I couldn’t remember what he was talking about. It was A Little Piece of Heaven, which must have been on MTV all of two times – and he’d seen it! We never got to work together, but what a moment.

Did Cry – the haunting video and the equally haunting song – feel like the culmination of both of your creative taps?

Yes. People still want to talk about that video to me; it was a real moment in time. Elbow got me to recreate it for their Gentle Storm single – you know the crossfading faces? That was plan B; that was never meant to be the video. We wanted Torvill and Dean to skate to it, but they couldn’t do it when we needed them. We had to come up with something else sharpish, and that was what we came up with. Even after we’d shot it, we weren’t sure what we were going to do with it until we got into the edit suite. Then we started dissolving between faces and that’s when the penny dropped, and it got really interesting.

What’s the best 10cc album, and why is it Sheet Music?

Because we were a little bit more knowledgeable. It’s 1974; it’s our second album, so we’re a little bit more sophisticated – but we didn’t know it all then. Which from that point on we kind of did. We kind of knew who our audience was and what they might want.

Something that Orson Welles once said when he was asked about how he’d made Citizen Kane. He said one of the most important ingredients was ignorance: “I didn’t know how to do things, so I figured that anything I thought of would be possible.” Which he made happen. Not only by doing things like that, but thinking like that. That’s how you move a medium and the technology that drives it forward. If it’s too easy and too obvious, what’s the point?