"I cracked my skull and was in the hospital. And nobody called me": How America's most dysfunctional band grew to hate each other but learned to love again

Steven Tyler, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Hamilton and Joey Kramer on the making of Aerosmith's Music From Another Dimension!

In 2012, as Aerosmith released Music From Another Dimension!, their first album of all-new material since 2001's Just Push Play, Classic Rock despatched Boston writer Ken McIntyre to Los Angeles to interview Boston's favourite sons.

In this feature, which has never been published online before, the five members discuss – with characteristic frankness and humour – the falling out, the making up, the ups and downs of 'Brand Tyler', and the making of the album.

I’m sitting with Steven Tyler in a white-walled function room in a hotel on the Sunset Strip. The room has been hastily decorated to give it a thrift-store psychedelic vibe: Afghan rugs are tacked to the walls; a grand piano is littered with topless anime figures.

Like most people in Los Angeles, Tyler looks at least 10 years younger than he should. He’s wearing open-toed sandals that give a gruesome glimpse of the horrors that lurk below his ankles: his toes wrap around each other at crazy angles, in clear defiance of their natural order. It is these toes, mangled beyond recognition from decades of athletic stadium derring-do, that have got us here today, in more ways than one.

Tyler’s left foot was operated on a couple of years back. They straightened some toes, got him walking without blinding pain again. They also gave him fistfuls of high-powered painkillers, the kind of pills that can send an addict back into the fevers of full-blown fiending. The kind of pills that can make a man fall off a stage and break his face. The kind of pills that can break up a band.

All of this happened and more, including the inevitable high-fiving reunion. The result is Music From Another Dimension, Aerosmith’s first album of original material since 2001’s Just Push Play. That’s really the story here. Unfortunately, you have to wade through mountains of gossipy Hollywood bullshit to get there.

Since the 70s, press coverage of Aerosmith has always focused first on the druggy antics of the Toxic Twins, at the expense of the music. It’s so ingrained in them at this point that Tyler automatically spews facts and figures about who got sober first.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

So, is this article about Steven Tyler, millionaire drug addict? That’s up to Steven Tyler, really. In fact I never even asked him about drugs.

I had to travel 3,000 miles to talk to a bunch of guys who live in my neighbourhood. If you live in Boston and you want to talk to Aerosmith about their new record – or anything else – it’s remarkably easy to do. They’re around. Everyone I know who grew up here has an Aerosmith story, but they’re small, human stories: tiny conversations in line at the movie theatre; impromptu games of touch football on lazy Sundays; sharing a burger at the diner.

About 20 years ago, I ran into Joe Perry at the grocery store at 3am. I felt compelled to tell him that of all the Aerosmith rip-off bands, Smack were the best. He nodded and grabbed his bag of Fritos. All the big rock’n’roll shit – groupies, rehab, TV shows, open-air festivals – they do all that somewhere else. In Boston, like the rest of us, they take it easy and mind their own business. So I can see why they’d want to hold a press junket in LA; complimentary bottles of Voss water and interviews conducted on director’s chairs would just seem stupid back home.

It’s my first trip to Los Angeles so, naturally, I fuck it all up. My hotel room is half an hour away from where Aerosmith are, so on the morning of the interviews I walk there. This is a perfectly sensible thing to do in Boston, but in Los Angeles it’s a fatal error. Everything is so far apart that 30 minutes soon stretches to 60. And despite being mid-September, it’s one of hottest days of the year, peaking at 106 degrees.

By the time I get there, a sweaty, broiled mess, I’m just in time to meet Ross Halfin, Classic Rock’s photographer for the story and one of Britain’s most legendary rockarazzi. I sip Diet Coke and nibble on bacon at a table headed by Ross and flanked by two Japanese stewardesses, Joe Perry’s ‘right-hand man’ and a blonde Sony executive. I am mostly ignored, unless I’m getting grilled by the notoriously prickly Halfin. It goes like this:

“So, you call yourself Sleazegrinder?”

“Yep.” (Confession time: on more frivolous engagements, I do indeed call myself Sleazegrinder.)

“That’s a ridiculous name.”

“Okay.”

“Where are you from?”

“Boston.”

“Ugh. I hate Boston. It’s like England, only more boring.”

“You know, this is my first time in LA.”

“How the fuck is this your first time in LA? Was it your first time on an aeroplane, too?”

So, that was breakfast.

Later on, I’m led into a waiting room deep within the labyrinthine courtyard of the hotel. It’s International Press Day, so I spend the next four hours making (very) small talk with Japanese journalists and two friendly Germans who write for heavy metal magazines. A lifetime later, when I’m finally ushered in to talk to Joe Perry, I’m so relieved to be talking to another local that Boston is, naturally, the first topic of conversation. And for good reason, really.

There are very few bands in operation so closely identified with the town they’re from. For decades, they’ve been the pride of Boston, along with the Red Sox and our ridiculous accent. To this day, on the streets of our city you can get punched for uttering a discouraging word about the band, or get laid for a righteous ’Smith logo tattoo.

“The funny thing is, we always felt like outsiders in Boston, even though we had lots of friends in local bands,” says Perry, describing Aerosmith’s early club days in the late 60s. “We never played there that much. We didn’t want to play five nights a week, we weren’t a cover band, and there was no real rock scene at the time. There just wasn’t a place for us. You covered rock songs on the radio or there just wasn’t any interest.”

It wasn’t until the band broke through nationally with their 1973 debut album that their home town finally took notice and Aerosmith became Boston’s new favourite band.

“That’s true, even though there was a band in town called Boston,” Perry grins. “I always thought that was interesting. They were never really a band. And I think that speaks volumes about that underground energy we had. Even though they were from Boston and they were all Boston guys, people knew it was really Tom Scholz. He wrote the songs and found a few talented guys and put these incredibly successful pop records out, but they weren’t a ‘band’ to speak of. But with us, we were a band. We weren’t looked at as a Boston band, though. By the fans, yeah, but not by the media. Not for years.”

Perry, like most of Aerosmith, still has a home in Boston. More importantly, he still considers it home. But he’s still pissed off about the club days. “I grew up there, and I’ve lived there my whole life. But I don’t feel like we’re part of Boston’s musical history, no. I just feel like we were always considered the outsiders. Again, by the media. The fans have always been there for us. But we were selling out 5,000-seat halls in Detroit long before we were selling houses half that size in Boston.”

Perry – who still looks like the square-jawed, guitar-slinging bad-ass from 1975 – is Aerosmith’s most disarming member. Thoughtful and introspective, his quiet, cool demeanour belies the decades of physical, chemical and financial wreckage his band have survived through these past 40 years. He just doesn’t seem like the lizard-in-a-bottle type. I have a note in my pocket that says: “See if Joe is sober.” I don’t bother to ask – he looks pretty bright-eyed to me – but I do wonder out loud why people still care.

“Well, we kind of opened that door,” he says. “I think a big part of it was people had to know we were on the level, because we had to cancel so many shows when we were fucked up and we weren’t playing great. The last shows before I left the band [in 1979], some nights would be great, but some nights just weren’t. Every night has to be great, and we just weren’t living up to our own standards.

"So the band just had to rethink everything. We’d reached a certain level, and it’s like, what do we do now? There’s only a handful of bands that have stuck together as long as we have. Everybody else died or broke up, and that was it. So when we came back in the 80s, not only are we going to get back together, but we’re going to tell everybody we’re sober. We had to. We’d burned a lot of bridges.

"So that part followed us around. And the tension between Steven and I, all through the 70s, that followed us too. And it made for good press. ‘How could they be that way? How could they be on stage and make records together and still be at each other’s throats?’”

Well, that is a good question.

“It’s pathetic. We just can’t find anything better to do,” laughs bassist Tom Hamilton. “Really, we’re just five guys that love playing with each other. It’s worth all the trouble.”

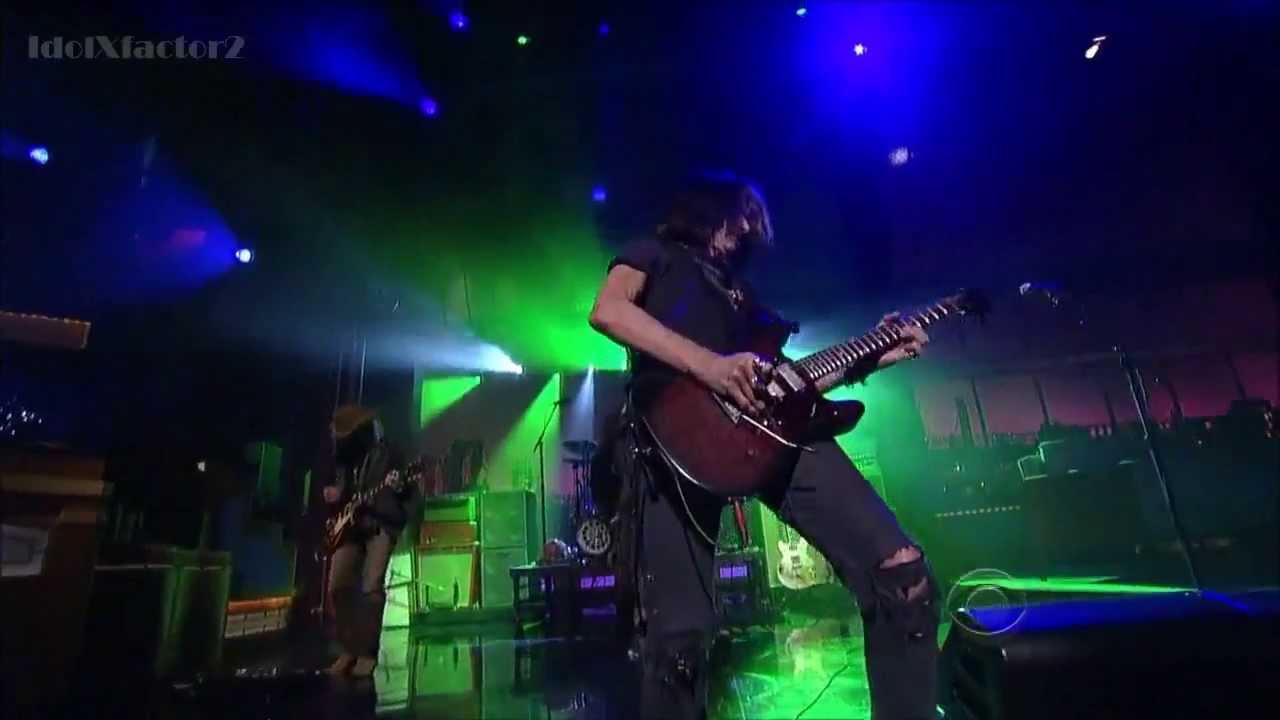

Hamilton, guitarist Brad Whitford and drummer Joey Kramer are the unsung heroes of Aerosmith. The fact that they’re doing their interview together, in a tinier, colder room, during their lunch hour, no less, stands as a testament to that. These are the guys who deliver the goods, without pageantry or complaint.

“That’s our job,” Hamilton shrugs. “In any band, someone’s got to fill that role, and somebody’s got to be the peacock.”

It’s been a very eventful few years for Aerosmith’s preening peacock, Steven Tyler. In August 2009 he fell off the stage in Sturgis, South Dakota, breaking his shoulder and cracking his skull. It was assumed his mishap was drug-related. Maybe it was, and maybe it wasn’t. Even he’s not sure.

“Yeah, I fell off the stage during the ZZ Top tour. I only went on that tour because I thought the band was over. Six months before that I was at Las Encinas [rehab centre] and I couldn’t walk. I went to a pain management clinic for my feet and they said: ‘Here, take this.’ So I was taking that stuff, it’s true. But I think I only had a beer before that gig, and I fell off the stage. My girlfriend said: ‘You weren’t even high that night! Why’d you tell them that?’ Well, I had to tell them something.”

The incident sparked rumours that Tyler was leaving the band to pursue a solo career. Soon after, while the band were on tour in Abu Dhabi, Tyler appeared to confirm people’s suspicions. “It was the last couple shows and we were in Abu Dhabi, and I did an interview with some English rag [Er, that would be Classic Rock – Ed.] and I said: ‘I need some time to think. I need some time’ – and this is the part that the guys obviously heard – ‘I need time to work on Brand Tyler.’

"What does that mean? Interestingly enough, Brand Tyler is what got me American Idol. I’m the guy who wrote Dream On. That’s what I am. But to hear it put in those terms? It scared the hell out of the band, and they said a lot of bad stuff about me afterward. It didn’t mean anything, though. I mean, it’s interesting: Joe does solo records. Isn’t that Brand Perry?”

A day after the Brand Tyler comments went viral, Joe Perry was playing a gig in New York with the Joe Perry Project when an impromptu reunion occurred. Tyler says: “I was living at [daughter] Liv’s house. She was off doing a movie, so I was in Greenwich Village, working on my book, doing OxyContin [a narcotic pain reliever] and waiting for some blow to come in so I could spend Christmas there and do cocaine again.

“The thing is, I heard what the guys were saying about me, and I was mad at them. Listen, I fell off the stage, I cracked my skull, I tore my shoulder, and I was in the hospital. And nobody called me. It really hurt me. It hurt me bad. I didn’t say anything, but I was angry at the guys and I was still high. I wanted to kill them.

“I found out that Joe was playing in New York, and I got into a limo with a bunch of my friends. I looked on the internet for what songs he was doing, and I figured an hour into his set he’d probably be breaking and going into Walk This Way. Well thought out for a guy that was living at my daughter’s house, still snorting Lunesta [sedative].

“I went because I didn’t like the rumours that were going around that they were looking for another singer. Short of getting a gun and shooting someone, I didn’t know what kind of press I could do, or cannonball I could shoot out of, or rock in the pond of life I could ripple out of to let them know how I felt. So I thought, I’ll go down, walk in and do the encore. And that’s what I did.

“I looked out at the audience and they roared when they saw me and Joe together. I said: ‘The band is not broken up.’ Then I said some fantastic thing about: ‘Joe, you may wear a coat of many colours but I, motherfucker, am the rainbow.’ I said something like that. I know it was interesting at the time. It was so off the cuff, but I hated everyone thinking that Aerosmith was over. I knew it wasn’t.”

He was right. But first there was more rehab, a solo pop single (It Feels So Good), and a stint on reality TV as a season-long judge of singing competition American Idol. By 2011 Brand Tyler had come into full flower.

“I went to Betty Ford, and six months later I did American Idol. I honestly did it because my feet hurt. But I was doing Idol, I was on the cover of Rolling Stone, my book was coming out, I had a hit single. That was all from getting sober.”

Meanwhile, his band were still scrambling for something to do, and the rumours of a Tyler-less Aerosmith heated up once again. From the band’s perspective, though, that was never a real option.

“I was just being practical,” says Perry. “At the time, Steven was going through a mountain of personal stuff, and basically he said he wanted to take two years off. He didn’t know what he wanted to do, but he wanted to take two years off to do ‘Brand Tyler’.

"So the rest of us are on the phone going: ‘What are we going to do for two years? The band’s playing great, let’s talk about getting another singer until Steven comes back. Would we call it Aerosmith? No, it wouldn’t be Aerosmith. Should we even talk about doing that, or should we just take the time off?’ I wanted to work on the Joe Perry Project anyway.

“Somewhere in there, a few quotes hit the media and then it exploded. But it was strictly a matter of Steven wanting to take a couple of years off and us sitting around wondering what we’re gonna do. It was all just talk, that’s all it was. It was never etched in stone, and it just never felt right.”

“It never went further than discussion, but we had to talk about it,” says Kramer. “The reality is that we have always been at least ready to go, in some fashion or another, crippled, hobbling along or in full gear. We’ve always been ready: let’s go do a record; let’s go tour. But now, all of a sudden, Steven had a job. And it was like, he’s gonna be busy a lot. So we talked about it. It never went beyond that. But even if it did, it would never have been Aerosmith.”

Tyler’s success on Idol propelled him to mainstream fame, but it was clearly not a permanent gig. Tyler claims that he mostly used the experience to promote his autobiography, Does The Noise In My Head Bother You?. And when the season was over, he quit.

“American Idol made us a household name,” Perry says, “but Steven wasn’t doing what he was meant to do. He can be really funny at a party, but put him on a panel like that and that’s not really what he wants to do. He can do it, but that’s not where his heart is. His heart is in singing in front of 10 or 20,000 people. But he did it, and now there’s a whole new batch of kids finding out what Aerosmith really is.”

“At first I think the band was mad at me for doing Idol,” Tyler says. “I knew it would be good for us, but I didn’t know if I would be ostracised and sent to the cornfield or what. But at the time, I was feeling great. I started writing these songs with Marti [Frederiksen] and it felt so good. But I started feeling pressure from my label, who said that if you want to go solo – and I did – you gotta get off Sony first; you gotta do one more album. So I woke up one morning and I thought, I should call Jack [Douglas, producer]. I had just gotten out of Betty Ford six months earlier, and Jack was sober too, so I thought: ‘Call Jack!’

“I remember I was at the Laurel Canyon country store and I called him up and said: ‘Listen, Joe’s still high, but we’ve got to do this.’ And Jack joined forces. He’s the sixth member of the band. I just thought, whatever we’ve gotta do, whatever we’ve got, we’ve got to do this album and get off Sony. And I knew Jack could do it. So I called Joe and Tom and Brad and Joey. I said: ‘I promise you, Joey, we’ll get a song a day. Brad, Tom, I promise you, and we can start this album off by all of us having songs that we wrote on it.’ I knew that would tweak their dial.

“After Idol was over, I went back to Boston, Jack joined us and the rest is history. It’s that simple. We got sober, that’s it. We were there before, but we weren’t really there. Now we are. People will see the difference on stage between me then and now. I’m on fire right now. Joe’s off the drugs he was on three years ago, the cocksucker, and me too – we’re now back in a room talking to each other. I’m not talking to the drugs, he’s not talking to the drugs.

“There’s another thing I realised: what if this is gonna be our last record, and what’s it gonna take to get Joe back and Brad back? I need to get sober first, and the rest will follow.”

The Music From Another Dimension album really is a patchwork affair. A collection of old songs and half-forgotten licks written by Tyler and Perry, alongside new songs penned by various band members and outsiders like Desmond Child and Marti Frederiksen, who also helped produce several of the tracks.

Production on the album originally began in 2003. The band were still riding the waves of their enormously successful 80s comeback at that point. 2001’s Just Push Play was a platinum-selling smash anchored by a US Top 10 hit, Jaded. Tanned, rested and ready, the band set out to create another radio-rattling monster. But from here on, things got rough.

“This album wasn’t like Chinese Democracy,” says Tom Hamilton, anticipating my comparison, “because it wasn’t officially underway all this time. The record’s always been in the future. For some of us it couldn’t come any sooner; for some of us it was, ‘Let it happen when it happens. Let’s just hit the road and have a blast.’ I’m very attracted to both of those ideas. But finally we got to the moment, and it was great to do it. A new record is a big missing link in our equation.”

“We tried to make this record probably three times,” says Perry. “When you go to make a record, there are certain protocols that are met. You’ve got a record deal, and the label gives you a certain amount of money to make it. Money goes out to the producer, goes out here and there, so as soon as you start making it the machinery starts. That happened three times before we actually made the record.”

One early attempt involved Rick Rubin. Or “Whassisname… that fat guy,” as Steven Tyler calls him. “We went in the studio with him one night to see how it would work,” Perry remembers. “That was miserable. We just didn’t click.”

Because of Rubin? “Because of us. We were still getting fucked up. We weren’t in the right place headwise. We were just realising we were a band again and that we were able to work together, but we were still fucked up. That’s why we had to make a big deal of telling the world we were clean, because nobody was buying it at that point.

"So when we went in with Rick and had this horrible session, I remember waking up the next day and calling Steven and saying: ‘This is shit. We suck.’ Obviously we worked with him on Run DMC but, like I said, we’ve known him for years but it just didn’t click.”

Soon after, the band got in touch with an old friend: Jack Douglas. Douglas produced most of the band’s 70s albums and is considered by everyone involved to be the ‘sixth member’ of Aerosmith. If anyone could rally the troops, it was him.

Unfortunately, it turned out that nobody was in the mood for rallying, so instead they recorded an album of blues covers, 2004’s Honkin’ On Bobo. It may have been a fun exercise for the blooze-loving band, but it wasn’t exactly what the hardcore ’Smith fans were after.

“Getting into the studio with Jack and doing the Honkin’ On Bobo record, that was supposed to be this record,” says Perry. “We got into a room, turned the tape machine on and it almost happened by mistake. We were playing at my place in Boston, the Boneyard. The five of us got in there with Jack, and by then it became pretty clear we weren’t going to be able to buckle down. Nobody was in the right headspace. There was family stuff going on here, there was physical stuff going on there, we had just come off the road, the timing wasn’t right.

"But we did have time to do Honkin’ On Bobo. What that gave us was a chance to work with Jack, and a chance to work on music in a room together, which we hadn’t done in years. We had the freedom of not writing anything new, we got to play a bunch of our old favourite songs, we got to be creative in the studio, and it gave us something to tour behind. But it wasn’t the record we wanted to make.”

“Jack was great,” Tyler remembers. “Even though some of us were still using at the time, it was obvious to me that there was a chance. So you know what? Even if we were still high, one of the great things about Jack is, as long as he was sober, even if we were all high, he would have gotten something out of us.”

Honkin’ On Bobo hit the shelves in March 2004. The rest of the decade, and a chunk of this one, had been dedicated mostly to nonsense, to reality shows and pratfalls and inter-band bickering. There were fitful studio sessions, a legacy tour, some health scares, Brand Tyler, and the Great Replacement Singer Fiasco. But eventually, in 2011, the band got back in the studio and finished the record. Everyone in the band unanimously thanks JackDouglas for dragging them to the finish line.

“We were all of mutual mind, wanting to do the record,” says Kramer. “We had a couple of false starts, but what sealed it for us was when Jack came onboard. With Jack back, it’s comfortable, like an old shoe.”

“Everybody trusts Jack,” says Hamilton. “The fact that he’s going to be the producer eliminates a lot of what keeps us out of the studio. When everybody is on board with using Jack, it’s like, what a relief, now we know what the project’s going to be like and everyone can relax and get a chance to have a voice on the record.”

“He brings fun to the table, and when you have fun doing something it usually comes out pretty good,” adds Kramer. “We have a lot of laughs with him. We were all in the room together playing. That’s how we did the tracks, we did them all live again.

"That’s how we made Rocks and Toys In The Attic. We did it that way. This time, everything fell into place. Everybody had the same hunger and wanted to do it at the same time. Being in a room together, having a good time, with Jack producing, those are the main ingredients for this album.”

Of course, a cynic might say those aren’t the only ingredients: that there are also a few reheated leftovers involved and, in classic Aerosmith tradition, a sprinkling of resentment as well. One issue that both Tyler and Perry are clearly sensitive about is how vintage some of the songs are. Sure, they’re ‘new’ in the just-released sense, but a good portion of the Tyler/Perry numbers on Dimension were reworked from previous song-crafting sessions.

“I took a couple licks that I knew we had there,” notes Tyler. “They were just sitting there. The song Out Go The Lights was originally Bobbing For Piranha [from the 1989 sessions for Pump], but I just never wrote lyrics to it. It was a great Joe Perry lick, and I arranged it with the band a gazillion years ago, but we never added any lyrics and I knew the lick was so good. Jimmy Page would have paid good money for it. All I had to do was finish it. So for five months I just locked myself in and wrote the songs.”

“All those times getting started, getting ready to make a new record, there were more and more demos building up,” adds Perry. “Songs, ideas, riffs. We went in with all this material, and some of it, it just wasn’t the right time. As far as I’m concerned, a piece of music is done when we’ve finished it, when it’s been recorded, mixed, mastered. It doesn’t matter if I wrote the riff yesterday or 20 years ago. Some people don’t get that. They say: ‘Well, it was written way back when, so it must be a reject.’

"Well, that just isn’t true. It just wasn’t its time. That’s obviously true, or the Rolling Stones wouldn’t have a career, because half the songs on their early albums were old blues songs that were written years before. So you’re going to tell me that because they were written by Willie Dixon back in 1944 that they’re not good? I think the fact that there’s riffs that I wrote 20 years ago floating around on the internet, that doesn’t mean shit, because they weren’t ready to be done.”

Then there’s the issue with the writing credits. Music From Another Dimension was supposed to be a group effort, but Tyler brought in some outside writers.

“Using outside writers is like being married forever and using a sex toy,” Tyler explains. “Hello, it helps. Your wife’s gonna scream again like she did in the beginning. Whatever it takes. But it’s not like I didn’t include the other guys too. I mean, I get it. Tom wrote a song with me, Sweet Emotion. But that was 40 years ago, and he still needs to feel part of it. You know, he’s cried to me, ‘No one listens to my songs, no one likes them.’ But that’s not it, man. It’s that Joe and I went on a writing sabbatical and we came back with nine fuckin’ slam dunks. But he still wants to feel part of it.

"Everybody wants to feel part of the band. Do I feel bad I didn’t write another song with Tom after Sweet Emotion? Probably, but no. It was an era. But this time we came back and Tom had two songs, Joey wrote three by himself, we wrote a whole album together ourselves. Everybody’s got a piece of it, and it makes the band feel better. It’s like when you let your daughter sing for mom and dad. It seems silly, but it’s true.”

If that statement sounds dismissive – and it did – there’s a good reason for that. Tyler’s shadow looms large on Dimension. He had a hand in crafting nearly every song on the album, and a few of the album’s oddest diversions – like the country-pop duet with Carrie Underwood, Can’t Stop Loving You – were clearly his idea.

“Steven knows her from American Idol,” Perry shrugs. “I’d heard her sing, she’s got the pipes, she’s withstood the test of time. It wasn’t like, the person that won last week or anything. And Steven felt very strongly about it musically, he really thought it would work. And I think that it did. Mainstream country is weird, but I just think when those two sing together it works. It sounds natural. Whatever happens with it, that’s up to the fans.”

“When we were doing this record, no one liked [power ballad] Could Have Been Love. Not Jack, not the band, no one,” says Tyler. “They didn’t like Beautiful, which I wrote with Marti, they didn’t like the Carrie Underwood song. The band wanted to start all over. Once we got Jack in, they all felt like it was a shoo-in that they’d get their voices heard. But just because I had written all these songs, it didn’t mean we couldn’t do more.”

And they did. Tyler collaborated with Whitford on Street Jesus, with Hamilton on Tell Me, and the whole band ultimately added to Beautiful’s swirly flavours. But in many ways it sounds like Tyler’s record – and it probably is. Or at least a precursor.

“I’m doing a solo record next,” Tyler casually mentions. “I just am.”

How this affects the band is anybody’s guess but, for the moment, spirits are buoyant.

“I don’t see this band ending,” says Kramer. “If we’ve come as far as we have with the amount of bullshit we’ve been through, both as a group and individually, I don’t see anything stopping us, short of one of us dropping dead from a heart attack. There’s no reason to stop. As we’ve shown ourselves once again, by virtue of doing this record, there’s still lots of juice left.”

Perry, who is currently working on his autobiography, agrees with his drummer. “There might be a time when the gigs get fewer and farther apart, but we’re all in it,” he says. “I don’t foresee a time when we’d all go, ‘That’s it,’ and just pack it in.”

“Listen, I cannot command court in a fuckin’ stadium. Because of my feet, I just can’t do that any more,” says Tyler. “It made me cry when I realised that. But clubs I can do, and we will. The secret to all this is that we love playing together. Or maybe we love building it up and taking it down again. No, it’s not that,” he corrects himself. “It’s miracles. Maybe we just love making miracles.”

With the interviews over, racks of shiny rock-star clothes are wheeled in for tomorrow’s photoshoot. I’m not invited, nor am I invited to any Hollywood parties, soirees or happenings, with Aerosmith or anybody else. Even the German metal guy rejects me – he’s going to see True Romance in a graveyard tonight, but you need a reservation, sorry. My day(s) of munching fried pig flesh with Japanese stewardesses has come to an unceremonious end. A lone-wolf Satan rocker friend picks me up and shows me around, pointing out all the impressive rock’n’roll landmarks and where the downtown midnight cannibal gangs lurk.

Once it gets dark we drive to the Griffith Observatory, so we can view Los Angeles in all its profane glory. From the top you can smell the fear, inhale the desperation in greasy lungfuls. All the last cowboys rushing to stake their claims before the whole ugly mess breaks off and splashes into the ocean. Millions of flickering lights, each one determined to shine brighter than the rest, even if it kills them or mangles their feet into mush.

I can see why Steven Tyler likes this place so much. I can also see why the rest of the band like to get on airplanes and fly back home. This is no place for boys from Boston, even notoriously bad ones. From up here, the band’s conflict of interest becomes obvious. Blame it on the pills, American Idol, Carrie Underwood or whatever you want: Steven Tyler has become too big for rock’n’roll and maybe too big for Aerosmith as well. That might end the band, or it might make it stronger. Either way, you get the lasting impression that things are never going to be the way they were in 1972, or ’82, or ’92.

But no matter what happens next, they’re still the skinny, snarly motherfuckers from Boston who wrote Dream On and (successfully) did more drugs than any other band, ever. They’re still the best-selling American rock band of all time. And considering that rock is dead – at least as we know it – they always will be. And, most importantly, the fire still burns.

“I live for Aerosmith,” Tyler told me, in a quiet, confessional moment. “I couldn’t be a mechanic or a cook or even a piano tuner. I need to sing. That’s what I do. I have grown these wings being in Aerosmith, and when we are not on tour my wings get heavy. I don’t like walking around on earth. Because we’ve flown for 40 years together, my wings are heavy when I stand on earth.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 178, published in December 2012.

Classic Rock contributor since 2003. Twenty Five years in music industry (40 if you count teenage xerox fanzines). Bylines for Metal Hammer, Decibel. AOR, Hitlist, Carbon 14, The Noise, Boston Phoenix, and spurious publications of increasing obscurity. Award-winning television producer, radio host, and podcaster. Voted “Best Rock Critic” in Boston twice. Last time was 2002, but still. Has been in over four music videos. True story.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.