“Various line-ups sprang into existence just because someone said, ‘I’ll be your guitarist – I’ve got money.’ They felt like drunken shags. I gave in, but I hated myself for it”: When Robert John Godfrey rebuilt The Enid after 21 wasted years

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

After a winter of discontent that lasted over two decades, symphonic rock pioneers The Enid sprang back into life in 2010 with a new line-up, a new album and a new attitude. Mastermind Robert John Godfrey talked Prog through some of the previous highs and lows.

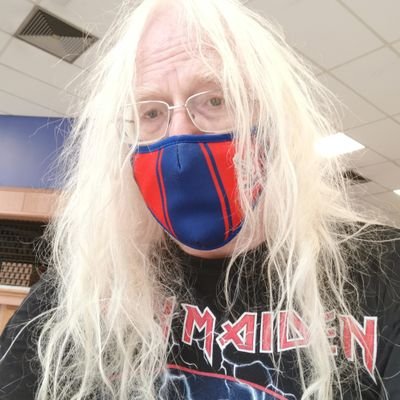

Like most people at his stage in their lives, Robert John Godfrey is relatively comfortable in his own skin. Having been out of the spotlight for more than two decades, he’s come to terms with the person that the past 63 years have contrived to make him – via the ups and downs of his group’s career and the shortcomings of a less than balanced personality.

“I’ve struggled greatly with clinical depression, so making a new album with The Enid has enabled me to regain some confidence in myself as a composer, which I lost after The Seed And The Sower,” says the all-round guiding force in a revealing opening gambit, referring to the last bona fide album he recorded with co-founding guitarist Stephen Stewart back in 1988.

As an openly gay man, a musician with an upper-class background and an artist whose work was never likely to reach the mainstream market, RJG has felt like an outsider for pretty much every step of the way. “Promoters, record label people, journalists – I’ve upset them all by not tolerating fools gladly and refusing to do a bit of brown-nosing,” he admits. “Concepts like ‘networking’ I’ve been unable to partake in.”

This writer first witnessed The Enid at one of their many Reading Festival appearances of the early 1980s, the stirring climax of which saw Godfrey conducting both band and audience through Elgar’s Land Of Hope & Glory, looking for like some Patrick Moore-esque loony. Which is exactly what he is, of course. “Aaah, yes,” he reminisces warmly. “It had been pissing with rain all day and I said, ‘Sun, show yourself!’ Lo and behold, out it came!”

Meeting him The Enid’s Lodge studio in Northampton, he’s exactly as you’d imagine, save for the recent shedding of two and a half stones in weight (“to avoid dropping dead before I finish the job”). All bushy beard, open-toed sandals and sporting a jacket presumably bequeathed to him by a schoolteacher from the 1960s, he’s outspoken and at times refreshingly candid. Frustratingly, he only discusses certain crucial matters with the tape switched off.

As we listen to The Enid’s comeback album, Journey’s End, he sits with eyes closed, stroking his dog Elsa. Prog, meanwhile, is equally lost in wonderment at its crescendos of mellifluous, symphonic sound. Godfrey explains that the record uses plants growing and withering on the vine as a metaphor for the equally temporary existence of humankind. “It is,” he says with finality, “the best thing I have ever been involved with. And that’s because it’s no longer just the Robert John Godfrey show.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

To contextualise his statement, we must travel back to 1967, when he abandoned a career as a concert pianist, dropping out of the Royal College Of Music to become Barclay James Harvest’s resident musical director. He oversaw the integration of a symphony orchestra to the rock music of 1970’s Barclay James Harvest and the following year’s Once Again.

He’s extremely proud to have been a pioneer. Asked if he was combining classical and rock before the emergence of such perceived contemporaries as The Nice, his tone escalates. “Oh, I was doing this long before them,” he bristles.

“Deep Purple made some sort of effort [with Concerto For Group And Orchestra, 1969] but that was a hotchpotch idea. With Barclay James Harvest, I was the first to actually integrate the two styles of music – as opposed to using an orchestra like some glorified keyboard. Followed shortly thereafter by Procol Harum.”

His fallout with Barclay James Harvest was fractious, though nothing compared to the legal storm of many years later when Godfrey claimed both co-credits and financial reimbursement for six early compositions including Mocking Bird, Galadriel and Dark Now My Sky. A judge would grant the credits (albeit acknowledging varying degrees of responsibility for each song), but due to the excessive length of time that had elapsed, overturned the cash call.

Had Barclay James Harvest stayed together with me in it, we’d have been as big as the Pink Floyd

“It was a curious situation, but I felt a strong sense of vindication,” admits Godfrey. “Despite the fact that they abandoned that direction, my work helped to establish Barclay James Harvest. Those albums are the ones that are most fondly remembered. Had Barclay James Harvest stayed together with me in it, alright, there wouldn’t have been an Enid, but we’d have been as big as the Pink Floyd. All the ingredients were there. That marriage should have continued. I still feel extremely hurt.”

With the help of guitar players Steve Stewart and Francis Lickerish, The Enid were born in the summer of 1973, the name taken from a fictitious girlfriend from Oldham. Their plan of adding a frontman, Peter Roberts, was torpedoed by his suicide on New Year’s Day 1975, but the group persevered as an instrumental entity.

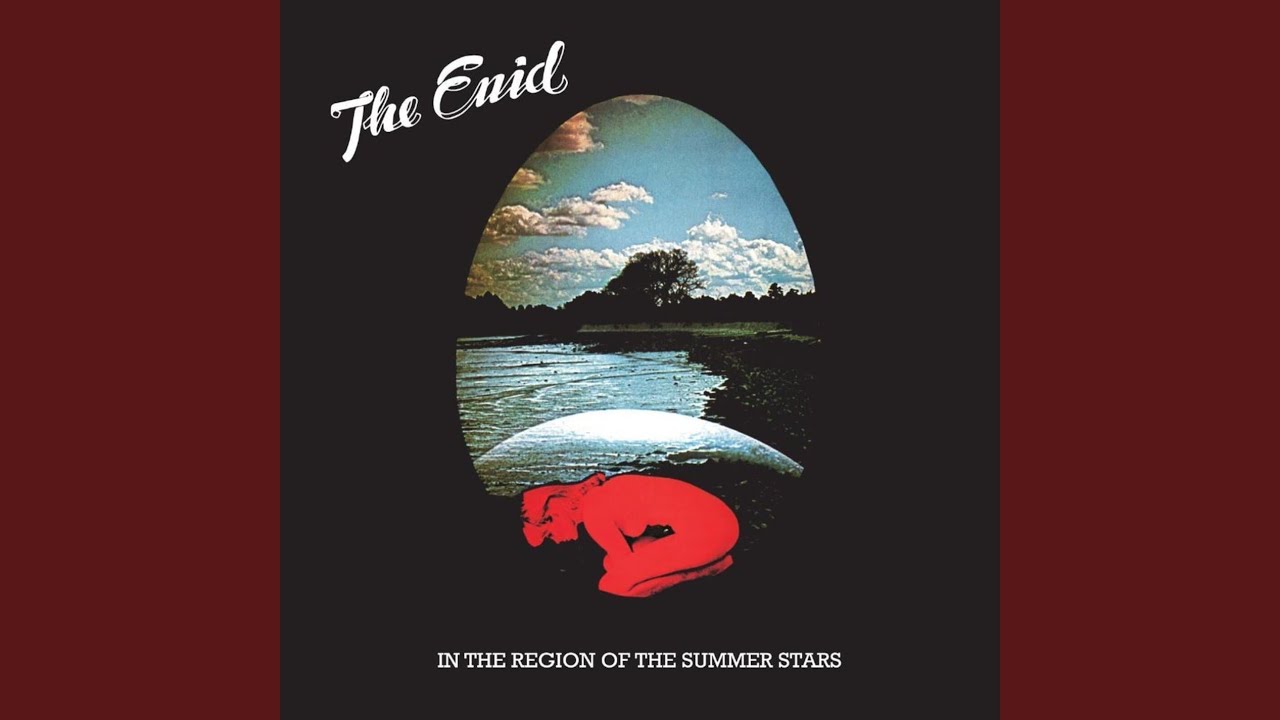

Godfrey claims he was forced to scrap The Enid’s debut album title, the concept of which was based on the tarot cards, after telling Charisma Records’ Tony Stratton-Smith that it would be called Voyage Of The Acolyte. When Steve Hackett released a record of the same name on Charisma in 1975, there was a whiff of thievery. The Enid’s title became In The Region Of The Summer Stars. “Voyage Of The Acolyte was a stupid title anyway,” he theatrically huffs, “so I’m glad it ended up with Steve Hackett.”

He recalls the band’s early years as “turbulent” – although during an appearance at 1976’s Reading Festival, they were called back for six encores. Their second album, Aerie Faerie Nonsense, arrived with punk-rock still reigning as the era’s fad. Amazingly, claims RJG, the more intelligent spiky-tops appreciated the sheer anarchic absurdity of releasing a concept piece about a young knight called Roland in 1977.

During the following decade, a row with the record company and the disloyalty of a trusted partner would force the band to take charge of its future. “The label said, ‘Robert, we need to sell some records. You must get a frontman and write some commercial songs.’ I replied: ‘Fuck you.’ And that was the end of it all.

A corrupt band associate was running up debts on our behalf. The bank manager turned told us we owed £90,000

“The guy that had signed us for a lot of money then left the company, Francis Lickerish left the band and I was all alone at the helm.” Godfrey erupts with laughter: “Which, of course was the absolute worst thing that could have happened!”

That wasn’t all:“A corrupt band associate was running up debts on our behalf. The bank manager turned up on the doorstep saying we owed £90,000. So we got a move on and finished an album, which was Something Wicked This Way Comes.”

He reflects: “I had to grow up pretty fast, but the experience provided The Enid with a new, staunchly independent, self-supporting and very creative lease of life that lasted for nearly a decade. Had that associate been a good boy, there’s every chance we’d have ended up with no further career.”

The group’s influence would spread wider than its sales – according to Godfrey, MI5 actually began to investigate them regarding the controversial Something Wicked This Way Comes, after he’d ‘outed’ Thorn EMI for alleged links with nuclear weaponry as he fought to regain the rights to their early albums. “It’s all anecdotal, but I believe it to be true,” he states, adding in a downcast voice: “And it didn’t work, because we’ve still not fucking got back those albums. Though we still might.”

In November 1988, The Enid split up after playing two sold-out shows at London’s Dominion Theatre. “All I’m prepared to say is that there were very good reasons why both Stephen Stewart and I had to move on,” Godfrey explains. “Things had come to a natural end.” He continued to release music sporadically, sometimes under the banner of The Enid but without direction. When reminded of a foray into acid-house with Tripping The Light Fantastic in 1994, he simply replies: “This was the beginning of my madness.”

After a long winter in somebody’s life, it’s only natural there will be a spring

It’s an era he has previously called a midlife crisis. “Exactly. I had no idea who I was and felt like everything I’d achieved was shit,” he says. “I suffered from writer’s block.” Part of the problem was Stewart’s absence. “I had depended on him to stop me obsessing over detail; working on two or three bars of music for as many years. Various versions of The Enid sprang into existence, just because someone said, ‘Let me be your guitarist – I’ve got money and I’ll buy equipment.’ They felt like drunken shags. I gave in, but I hated myself for it.”

Godfrey is unable to put his finger upon what changed in order to facilitate the band’s genuine rebirth, crowned first by last year’s triumphant comeback gig at London’s Bush Hall and the recording of Journey’s End. “After a long winter in somebody’s life, it’s only natural there will be a spring,” he shrugs impassively. “That first gig felt like walking up to the front door of a great mansion. The 21 wasted years washed away.”

Communication is restored with both Lickerish and Stewart – the former having agreed to make some guest live appearances and the latter possibly set to do likewise. However, neither was considered for a more permanent return to the fold.“We’ve all moved on,” says Godfrey dismissively. “Besides which, I’m firmly committed to the people that are now members of the band.”

Over the next five years the line-up – completed by vocalist/bassist Max Read, guitarist Jason Ducker and original drummer Dave Storey – plan to re-record all the band’s previous studio albums “with enhanced arrangements and in 5.1 surround sound.” They’re determined to headline the Royal Albert Hall in 2011.

“I will tour until I drop. People are seeing us now and saying, ‘My God, I never knew music like this existed!’” marvels Godfrey. “All we need is a chance. It may not materialise in Britain, but I believe it will come. Somewhere.”

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.