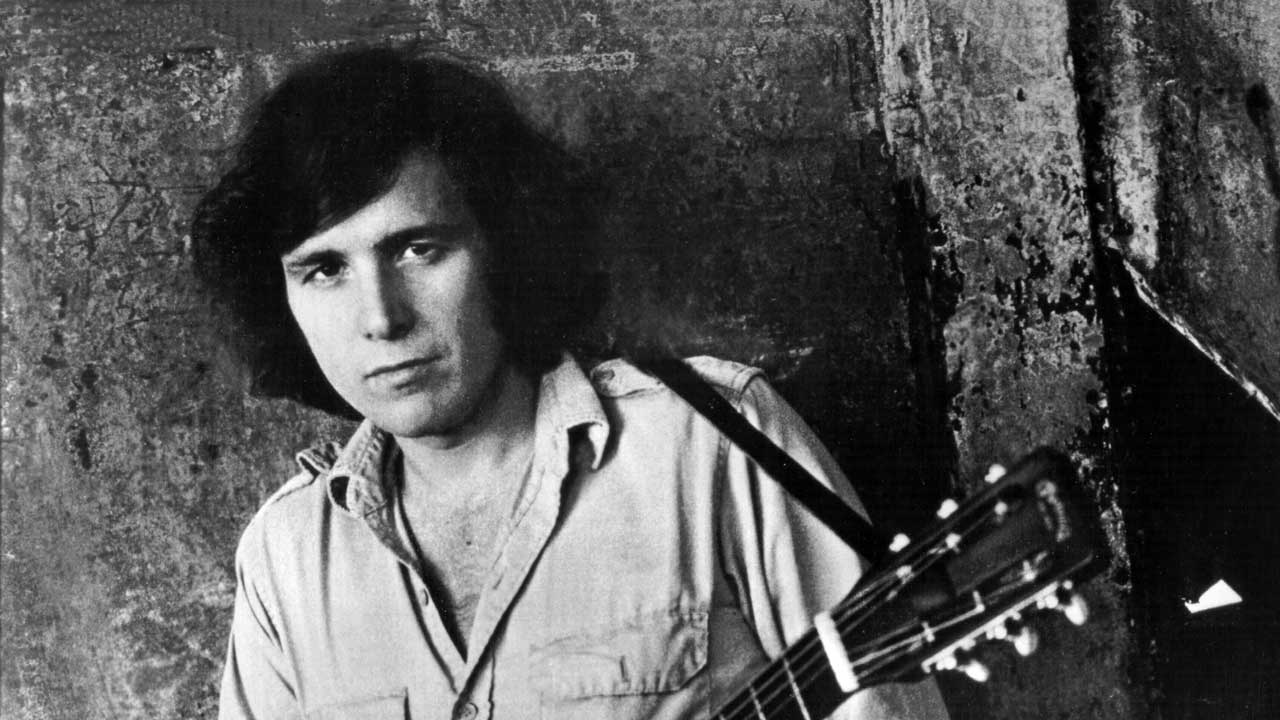

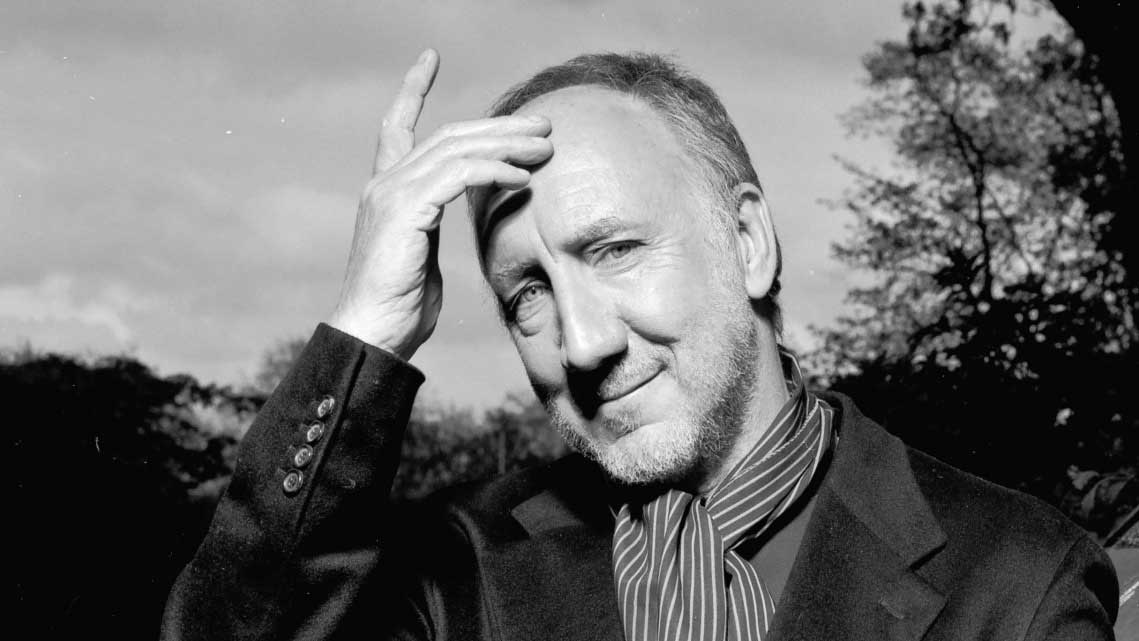

"My mother didn't particularly like the look of me and my dad didn't like the sound of me": Pete Townshend and the lifelong search for answers

The Who's Pete Townshend on parents, partnerships, punk, songwriting, the aristocracy, addiction, the internet and the ongoing search for extraordinary music

As the Second World War lurched to its conclusion, Peter Dennis Blandford Townshend was born in Chiswick Hospital in West London. Pete’s early years were shaped by both the grim austerity that defined the immediate post-war era, and an insecure family background. His father Cliff was a professional musician, and was mid-way through a gig in Germany with the RAF Dance Orchestra when informed of Pete’s nativity. His mother Betty, a former singer who’d lied about her age to enlist in 1941 and had ended up singing with her soon-to-be husband’s band, was so livid at Cliff’s absence that she moved out of the family home.

The couple soon reconciled, but their relationship - and consequently Pete’s childhood - was marked by an ongoing volatility that culminated in Pete being sent away to live with his “quite bonkers” grandmother, a rash decision that would ultimately engender significant and lasting consequences.

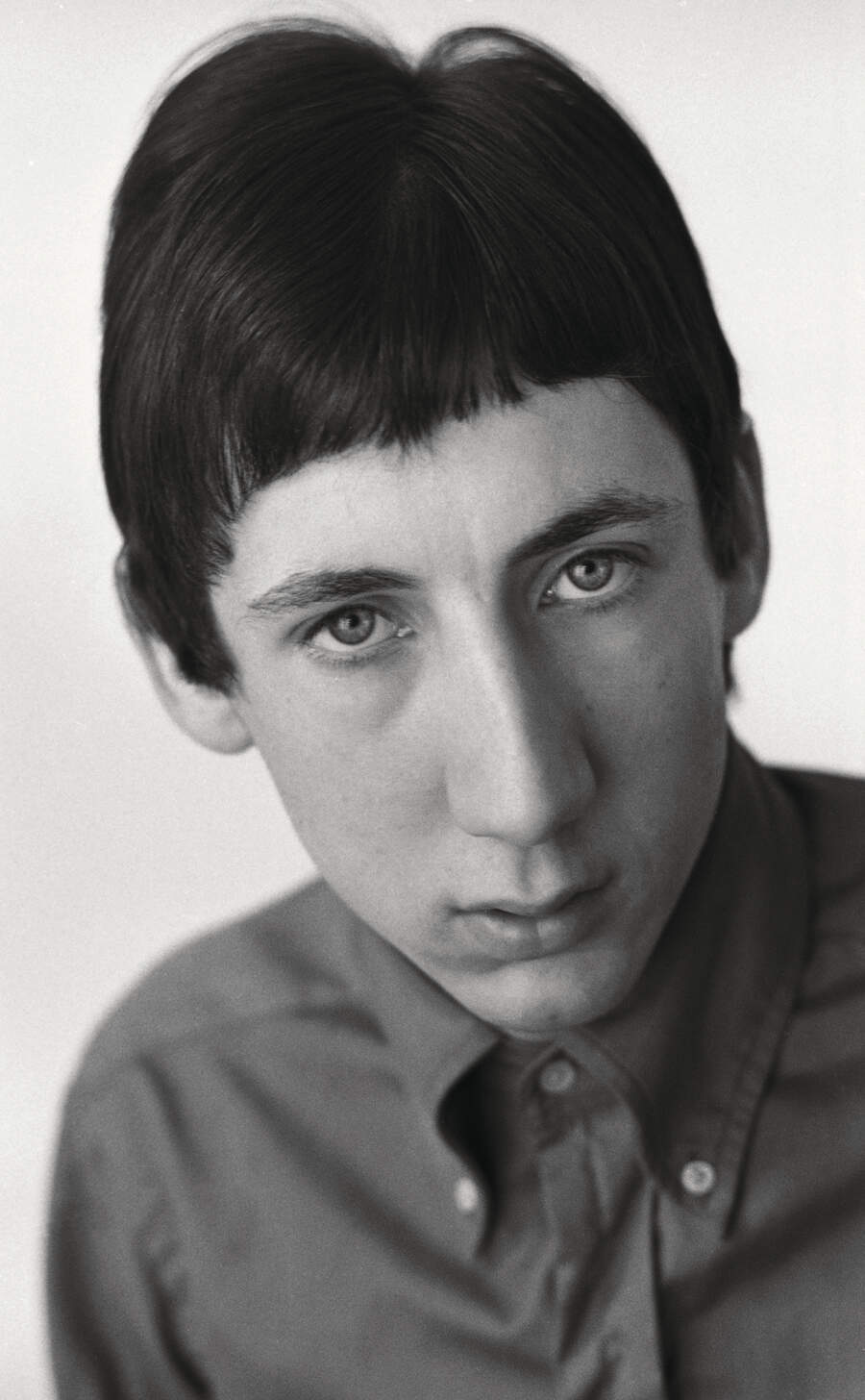

Surrounded by music, Pete initially sought solace in his father’s harmonica, but upon seeing Bill Haley’s Comets in Rock Around The Clock at the age of 12, decided that the guitar was “the only instrument that mattered”.

With skiffle arriving into the nascent British rock’n’roll zeitgeist in 1957, 12-year-old Pete took to the stage for the first time, plunking frantically at a banjo with dixieland jazz/skiffle hybrid The Confederates (who also included one John Entwistle on trumpet) at the Congo Club in Acton, West London.

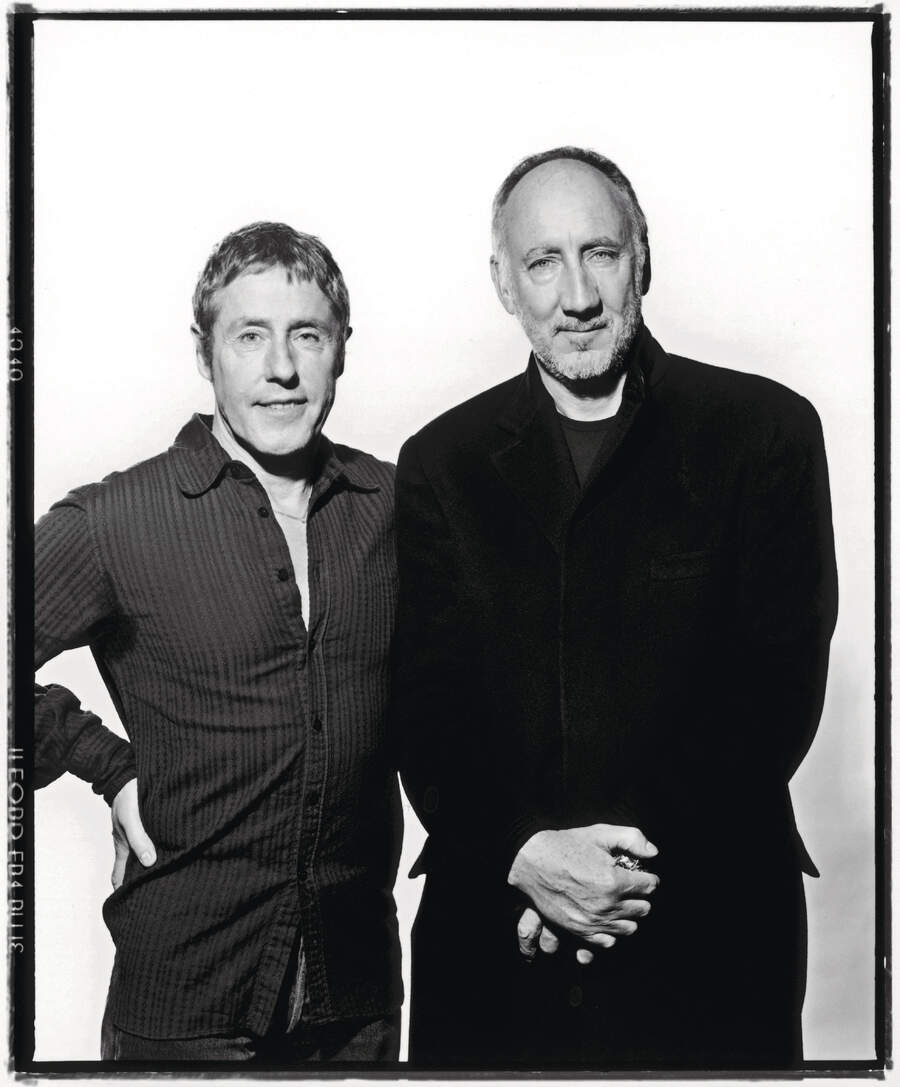

A few months after enrolling at Ealing Art College in ’61, Pete’s adept mastery of The Shadows’ Man Of Mystery saw him headhunted by bequiffed Teddy boy Roger Daltrey - a formidable old school acquaintance who’d been unceremoniously expelled for smoking - to join his band The Detours.

Townshend and Daltrey’s history heretofore had been somewhat rocky. The latter had intimidated a retraction from the former after Pete had loudly accused Roger of employing dirty tactics during a playground fight, but recently recruited Detour John Entwistle (who’d swapped his trumpet for a home-made bass guitar since Confederates days), had strongly recommended Townshend as a skilled guitarist.

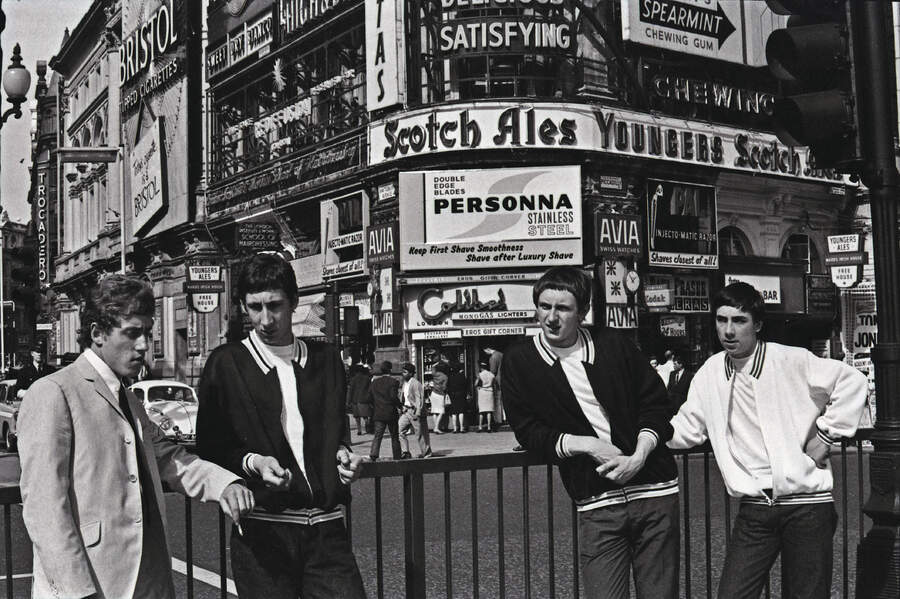

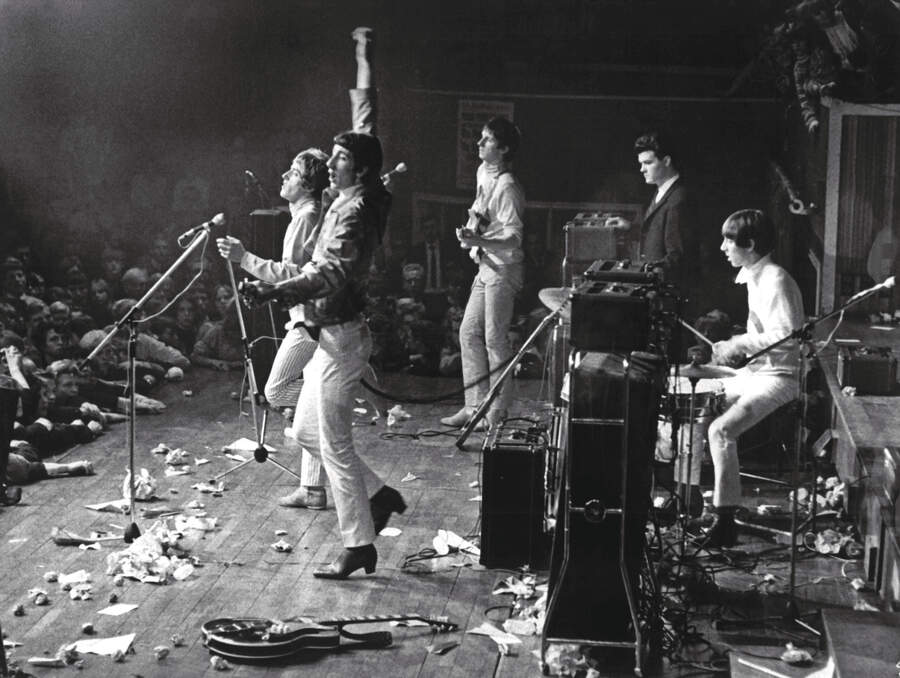

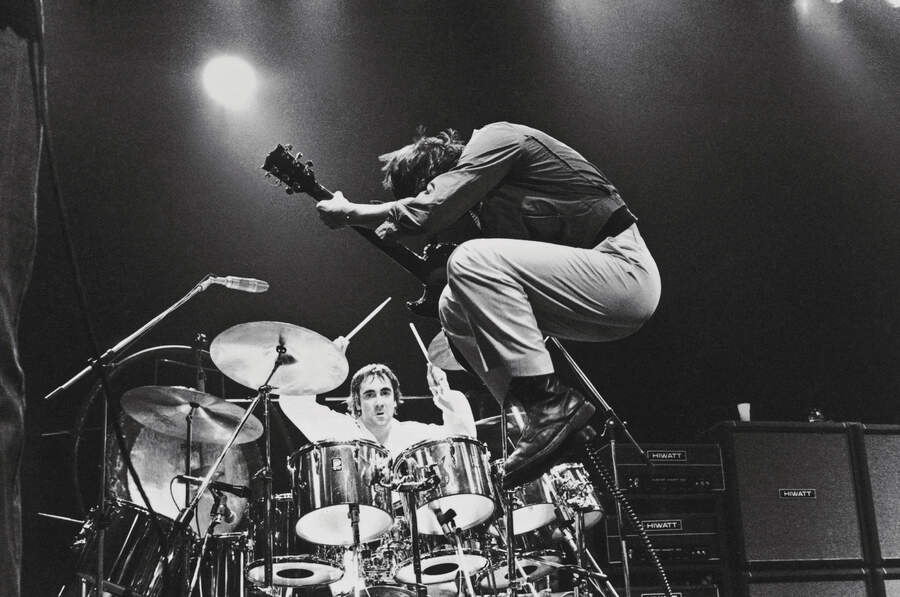

You’re probably ahead of me here, but in 1964 The Detours changed their name to The Who, brought in Keith Moon on drums, and via a series of era-defining Townshend-penned hit singles, an alliance with the prevailing mod scene and some of the most genuinely thrilling, autodestruction-driven, equipment-unfriendly performances in the entire history of hearing damage, ensconced themselves into the rock pantheon as one of the genre’s greatest and most progressive exponents.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Aside from performing with and writing for The Who, swiftly expanding the band’s remit from short, sharp, mod exemplars (I Can’t Explain, My Generation, Substitute), through ambitious conceptual pieces (Rael, A Quick One) and fullscale rock operas (Tommy, Quadrophenia), to timeless anthems of self-determination (Won’t Get Fooled Again, Baba O’Riley), Townshend has also enjoyed a concurrent solo career that has produced seven albums, recently collated in the eight-disc The Solo Albums set from UMR.

He founded Eel Pie Publishing, and was an acquisitions editor for publishers Faber & Faber. He’s been journalist, essayist, editor, author, producer, director and, on occasion, spokesman for his generation.

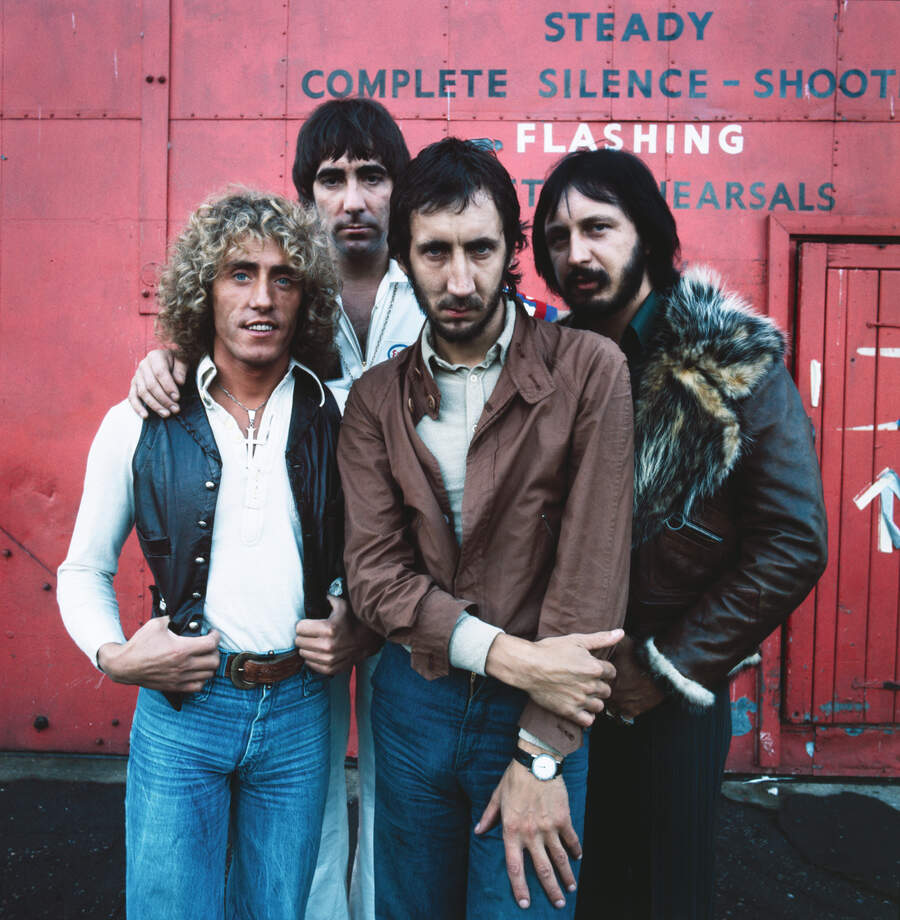

As we speak, The Who - a dozen albums and 22 UK top 30 singles into their six-decade career - are a week away from playing a brace of live dates at London’s Royal Albert Hall for the Teenage Cancer Trust. Townshend and Daltrey have yet to decide on a set-list.

Townshend has, after all, been trying to leave The Who since 1983. A few days prior to his thirty-eighth birthday in May of that year, he visited Daltrey’s house to tell him that he’d no longer be touring with the band. But, rather like Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone found in The Godfather III, there are some organisations that it’s just not that easy to leave. They will, to paraphrase Pacino, ‘pull you back in’.

For our interview today, Townshend doesn’t want to talk about The Who, but he cannot help but bring them up. They’re that intrinsically woven into his life. As we wind up, I ask him what’s next for him, and he simply assumes that I’m asking what’s next for The Who. Which, in and of itself, maybe says an awful lot about exactly who he is.

Did your parents encourage you into a career as a professional musician, or actively discourage you?

My dad was a professional musician in a dance band [Cliff Townshend’s premier gig was as alto saxophonist in the popular RAF-born jazz combo The Squadronaires], so playing pretty basic music, but he happened to be a very good musician. He often did orchestral sessions on bass clarinet and clarinet. He was really adept as a player and could read anything you put in front of him.

My mother had been a singer when she was young [Betty worked with both the Sidney Torch and Les Douglass Orchestras], and had been chased after by a bunch of music moguls. She was very pretty and had a lovely voice, but when the war ended and I was born [Pete arrived into the world on May 19, 1945, just 11 days after V.E. Day] they had the same life the rest of the general populace of the post-war era had, trying to make ends meet.

I was flung around from pillar to post a little bit in my childhood, and some of it, not all, was really quite gruesome. My parents split up for a while, they had their ups and downs. When I was about seven they got back together into a committed new relationship and started to try to have another child. I was an only child then. My dad continued doing various jobs, and my mum went out to work. She worked for the Regan showbiz agency. She worked in car factories. She did anything she could do to raise money. Then finally, to raise money on the side they opened a little junk shop in Ealing, where we lived, and I would occasionally do stints on a Saturday morning.

What I did for music was I played the harmonica. And this is not a fun story to tell – I don’t know why I even want to fucking tell it – but I had terrible issues with pollen and was pretty snotty all the time. So it wasn’t very pleasant to see this young kid with a big nose playing the harmonica with snot pouring out of every hole. So my mother didn’t particularly like the look of me, and my dad didn’t like the sound of me, even though I was a very good harmonica player, I could play chromatic pieces, but couldn’t read music.

We didn’t have a piano in the house, or a proper record player.

There was music sometimes, and I was embedded in the music scene around my dad, but he seemed to steer me more towards writing, towards poetry, essays and journalism, and then subsequently, when I started to draw quite well, towards art.

I didn’t get a guitar until I was eleven, and it was so crap I couldn’t really play it. So I didn’t start to learn to play properly until I was about thirteen, when I got myself a decent guitar. And at that point my mum leapt in like a fucking typhoon and started to really help me.

I was in a band with Roger Daltrey and John Entwistle called The Detours and we played pubs, clubs, Jewish weddings, stuff like that, and made quite a bit of pocket money doing that. My mum was a really big proponent of the band. She got us auditions, club gigs and a gig at the American Air Forces club in Queensway, which paid really well.

We bought a van, got really good gear and progressed quite quickly. This was between the ages of fourteen and fifteen. So by the time I got to art school at sixteen I was a pretty good guitar player. But my dad still didn’t show much interest in what I was doing.

It was dismaying, and it’s something I intend to continue to try to deal with in my writing and everything I do creatively, because I think we’re always deeply affected by our parents. If you have the good luck to live to be eighty years old, as I have, and are continually reviewing what you did as a writer – going back, looking at it, talking about it, tearing it to pieces and putting it back together again; why the fuck did I write that?; how the fuck did I write that?; and being asked: “What was that about?”and sometimes not really knowing, then digging in and finding out through self-analysis what some of this stuff is about – by the time you get to eighty years old you’re left with a few - slightly - burning coals.

I thought that most of mine would be with my mother, but they’re actually with my dad. So I’ve still got stuff with my dad left to deal with. So that’s the story. My dad didn’t encourage me as a musician, but he very much encouraged me as a writer.

You originally wrote I’m A Boy, Pictures Of Lily and Happy Jack as songs for yourself, not envisaging them as being suitable for, as you put it, “Roger’s group”. Does this indicate that you always saw yourself as enjoying a solo career concurrent to The Who?

I’m not sure it’s true I was always thinking about a solo career, but it wasn’t all about writing for Roger Daltrey. Roger wasn’t a particularly demanding member of the band. He was wrapped up in his own world. And very much a worker. He always drove the group’s van, and some of the journeys were very long. When we played in Blackpool he’d drive seven hours to get there, do the gig, and drive seven hours back. Nobody knew why he was so committed to it, but he was. He liked to be doing something, to be active.

The band members that were tricky were Keith Moon and John Entwistle, because their musical tastes were so extreme. John Entwistle was a huge fan of a guitar player called Duane Eddy, and his bass style grew out of that. He would have made a very good lead guitar player, but was consigned to being the bass player. He was always supportive of my playing and felt I was a good player, probably undeservedly in those days. Keith Moon arrived in the band as a Jan And Dean and Beach Boys fan, who I could hardly take seriously. So what I was trying to do was find a way to make the songwriting exercise, that I was involved in for The Who, amusing.

One of the primary differences between the earliest incarnation of The Who and the more familiar version, is Roger’s voice, because in the beginning he seemed to be shooting for a lower, gruffer, almost Howlin’ Wolf-styled delivery.

He was, yeah. Both of us were huge fans of Howlin’ Wolf and his guitar player, Hubert Sumlin. Hubert really inspired me. But Roger loved Howlin’ Wolf. We played two or three Howlin’ Wolf songs in our early sets at the Marquee club.

Once Roger started working from your demos, which always included your lead vocal, he seemed to adopt a higher register - perhaps unconsciously - attempting to emulate your naturally higher voice, which inevitably led to a more impassioned delivery, because he was always reaching for the top of his range.

Maybe. It’s a good theory, but I don’t think it’s quite right. Roger was always happy to be supported by high backing vocals. Even to this day. He’s always tried to make sure that when we do shows, we’ve good backing vocal support. And, of course, as we get older we can’t reach those high notes. And it’s something that when you miss it, you miss it.

On the Who’s third album, The Who Sell Out [1967], Roger told Kit Lambert Stamp until 1975] that although he loved a couple of the songs on the demos I’d done, he couldn’t sing them. So I sung them. The change for Roger happened with Tommy [1969], when we were faced with this strange dilemma, whereby Roger was going to sing the role of Tommy, but I was going to sing [sings in high register] ‘See me, feel me, touch me, heal me’. One day I went into the studio, heard him singing it, and it was quite clear that he could do it. He just never wanted to do it, although he does have a really good range.

You’ve always recorded complete demos in your home studio prior to presenting material to the band. Is that a process that’s driven your creativity, and broadened your songwriting into bolder areas you might not have so easily investigated if you’d adopted the kind of all-hands-on-deck approach of The Beatles circa Get Back?

You’re making a generality that everybody else did what The Beatles did, but they didn’t. Loads of bands, like The Hollies, got songs from songwriters, went in the studio, recorded them and got hits. Then there’s the more collegiate method of going into the studio, like Radiohead, and experimenting for two hours to come up with something, or U2 who’d work in a studio for six weeks to pull out a little snap, which then became their single.

Everybody had their own methods. But I’d write in a studio because I found it incredible fun. It was enjoyable. I don’t know that I tried to push the boat out until I started to get into serious concept work, and even then I played around a bit. A lot of the early conceptual I’m A Boy-type stuff was fairly light-hearted. The demo stuff was definitely something I did because I loved doing it.

How important was the support and encouragement of Chris Stamp and, especially, Kit Lambert as you sought to maximise your songwriting potential from A Quick One (’66) and Rael (’67) onwards?

Chris Stamp was an important figure in my life, certainly as a young man, but Kit Lambert was really important. Though funnily enough he had absolutely nothing to do with my solo writing, nothing. He’d let me down when we got to Quadrophenia [’73]. I wanted him to help me produce it and ended up having to produce it myself. Which might be one of the reasons it has such integrity. I don’t know if that’s the right word, but it has a flow to it. Kit got very sick halfway through the early sessions in Battersea and I sacked him, basically. He never came back. He went off to New York, worked with Patti LaBelle and had a couple of hits. So he seemed quite happy, but he never came back to me.

The first producer I really came across was Ronnie Lane. Ronnie was a good friend and he always wanted me to work as a solo writer. In fact he went further. He said he felt that, and this isn’t uncommon, a lot of people have said to me: “Pete, you’re wasted in The Who. It’s a shitty group. You should go off and do whatever your heart desires.”

A lot of people know that I’ve had to subjugate some of my more ‘art school’ ideas in The Who. I’ve drifted into it with stuff like Quadrophenia, Tommy and a few other things. But what’s really interesting is that even when I came to do my solo albums, and attempted to conceptualise some of what I was doing, a good example being White City [1985], I failed. I tried to do a stage play of Psychoderelict [1993], which was a disastrous idea.

They were brilliant, wonderful, crazy failures, but they were failures, and the reason they were failures was because I was pushing the boat out too far.

When I tried to experiment within the auspices of The Who, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp were important, but the most important person was probably Roger. Not because he put up barriers to my experimentations, but that he had a much clearer idea of what the outcome might be if we ended up committing ourselves to a particular project.

I had a very easy ride with The Who with Tommy. They supported me a hundred per cent right the way through it, and in the middle of it I was quite lost. With Quadrophenia I was quite certain of what was going on, but Roger didn’t support me completely. He knew it was good, but was at a point in his life where he’d started to build a dramatic understanding of how he operated as a singer, and he didn’t want to be doing an album about a kid called Jimmy, he wanted to be doing an album about a boy called Roger [laughs].

Nonetheless, he battened down with me in the end, and we all got behind it. But Quadrophenia was a tough journey for me, because while we were recording it, and I was producing it, doing the demos at home, the sound effects, orchestrations and all that stuff, I was working on the score for Ken Russell’s Tommy movie at the same time, so it was quite heavy work.

So what’s my point? My point is that I’m perfectly happy to work on my own.

John Entwistle was a silent partner in a way. He was incredibly supportive of everything I wanted to do and was quite happy to occupy his own corner in The Who. He wrote some really good songs: Heaven And Hell, Boris The Spider, Uncle Ernie, incredible songs. His Cousin Kevin and Fiddle About served Tommy in a way that I could never have done. He was also very supportive of everything I did on my own. On the other hand, I was very encouraging and supportive of him pursuing his own solo career. I helped him build his first home studio and get to the point where he could make demos.

It’s difficult to look back and generalise, because every project had a different story.

What’s the story behind 1972’s Who Came First?

Because rather than being a debut solo album project in the accepted sense, it was more a catch-all collection of existing pieces that weren’t widely available. In the late sixties and early seventies, the Grateful Dead were providing a stereo feed on the side of the stage where people could bootleg their concerts. We didn’t do that, but did record our shows. Bob Pridden, our sound man, used to record them, and after shows, we’d sit, have a few drinks and listen to them, imagining that one day there might be a live album.

Meanwhile, in sixty-seven I’d got involved with the tribe of the Indian master Meher Baba. I was really impressed with all the people I met, loved their company and felt - after all the rigours of psychedelia, the hippie movement and the failed revolution of the Mick Farren/International Times years - that this was a decent thing for me to study.

And the subtext was that I was surrounded by artists. Ronnie Lane had become a follower, through me, but there were artists: Dudley Edwards, who’d painted John Lennon’s Rolls Royce; Mark Kennedy, who went on to do the Tommy sleeve; some actors, writers, journalists. And we all got together one day and decided that it would be really nice to do a Happy Birthday album for Meher Baba with essays, artwork and some original songs.

Meanwhile, The Who’s live shows were being pirated and Decca were angry we weren’t doing anything to stop it. I’m not quite sure what we could have done to stop it. They were also angry that I’d put out this solo album [two Baba-related releases, Happy Birthday (’70) and I Am (’72) contained solo Townshend material latterly re-released as elements of Who Came First] and sold it purely to a closed market.

So they came at us with two things. One was the Who Came First album, but prior to that Live At Leeds [1970]. Live At Leeds was an album we didn’t want to do, but were forced to by Decca. Similarly Who Came First. I didn’t want to do a solo album, so I just gathered up stuff… In fact there are a couple of songs I didn’t even fucking write on Who Came First. So it’s not really a solo album.

Ronnie Lane appears to have helped instigate your solo recording career proper when he presented the idea of the pair of you making an album together, ultimately released in ’77 as the collaborative effort Rough Mix. Why did you choose to go all in with Ronnie at that particular juncture, because you must have been pals for some time?

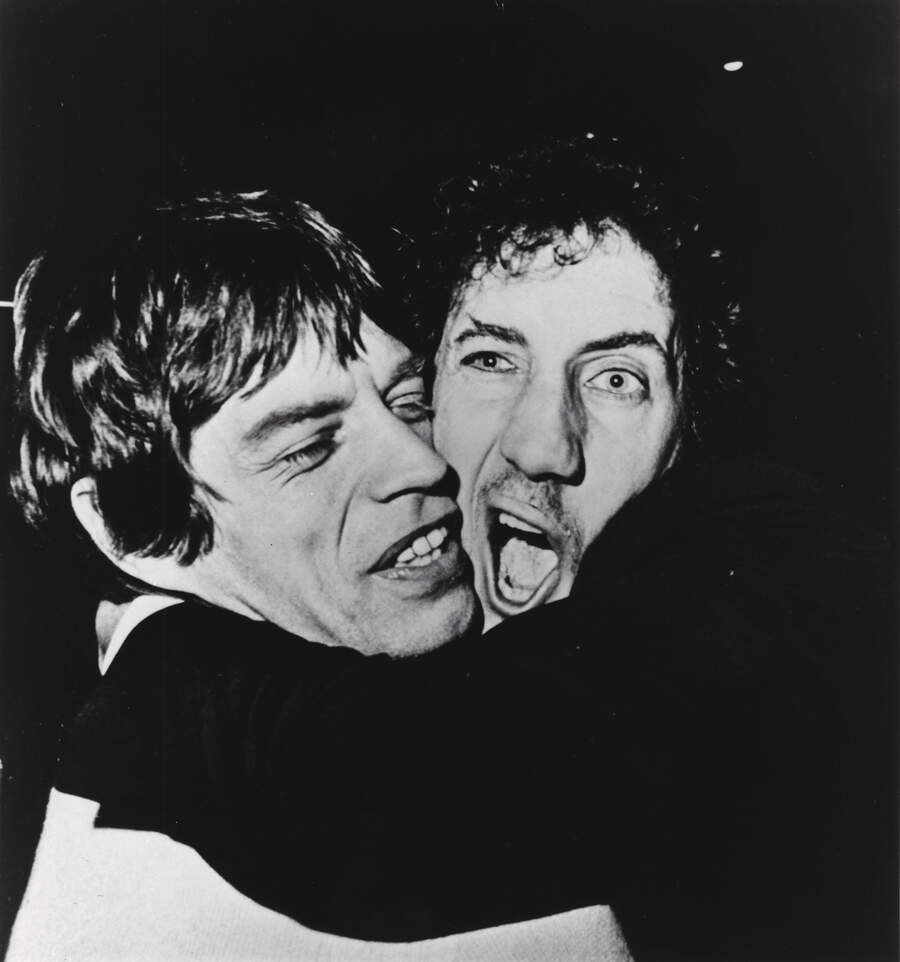

Yeah, we had been, right from the beginning. I’d been friends with both Stevie Marriott and Ronnie, but Ronnie and I got close. He eventually moved to Twickenham, where I lived, so we saw a lot of each other. We both liked to drink, shared a similar taste in music and were both friendly with other musicians - like Eric Clapton - and by then he was in The Faces, a subtext of the Small Faces.

Stevie Marriott had an emotional crash, not entirely drug-induced. He’d started working as a performer when just a child, so was pretty burned out by his early twenties. So Ronnie put a band together with Ronnie Wood, and subsequently Rod Stewart, called The Faces, while Stevie went off to work with Peter Frampton in Humble Pie.

The Faces and The Who did a gig together at The Oval [in 1971]. It was such a great day and they were such a great band. Rod’s got an incredible voice, their musicianship was lazy, super-cool, laid back, fun, funky, and Kenney Jones is a really tight drummer, so he held it all together. Then Rod became the face of The Faces, a sex symbol. And I hope he won’t mind me saying this, because I love Rod, but I think it kind of went to his head.

Anyway, Rod planned to move to California, and Ronnie had the option to join him there, to make a complete lifestyle change, but was incredibly dispirited by the whole idea, so he came to ask if I’d produce an album with him. I said: “No, I won’t produce an album with you, but I will do an album with you, if Glyn Johns will produce it.” So that’s where Rough Mix came from. It was an act of love, of friendship and of solidarity.

Meanwhile, word was out that I was in line to be asked to join the [Rolling] Stones. I was very close to Mick, not so much to Keith, but certainly Mick, and I said: “I’m not the right guy for the job. The Stones are my favourite band of all time, but I’m not up for it, but the guy that’d be fucking great would be Ronnie Wood.” So I got hold of Ronnie and said: “If they ask you, you must do it. It’ll be life-changing for you. You’re absolutely perfect for it. You’ve got the right energy, the right spirit.” He agreed, and that closed the door on The Faces.

We only set aside two weeks to make Rough Mix, but it struck me how deep Ronnie was starting to go as a songwriter. After all the bon vivant stuff that surrounded The Faces, he was a very serious fellow and now has quite a few disciples, people that want to echo the Ronnie Lane method of making music.

Those Rough Mix sessions marked the first time you worked with Peter Hope Evans and John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick, guys who’d become stalwart members of your solo band for years to come, as well as some old chums like Eric Clapton and Charlie Watts. The entire process must have been incredibly relaxed, enjoyable and rewarding.

Yeah, it really was. But it wasn’t all without difficulty. We didn’t know then that Ronnie had been diagnosed with MS [multiple sclerosis], and he was behaving strangely. He was being afflicted by really weird moods, and a couple of times he started to attack me. Not physically, but it upset me deeply because I’d reached out to him as a friend.

Going deeper with this, Ronnie really did despair of me being in The Who. Despaired of it. And looking back, my first wife, Karen, despaired of me being in The Who. And I’d probably say that my wife now, Rachel, occasionally despairs of me being in The Who.

You know, there doesn’t seem to be that much joy in it. It’s lucrative. It’s an incredible job to have. So many people would feel so lucky to have a songwriting job for a band like The Who. But it’s gone on a bit too long with two of us dying. And it does sometimes feel like flogging a dead horse.

So Roger and I are exchanging letters and emails at the moment, just saying that the most important thing we can do at the moment is support each other and love each other. That’s the only thing that’s important. It’s not whether The Who goes on for ever, or whether we do great shows, just that we don’t take it as seriously as we did in the beginning, because we can never, ever do that again. We were black swans, we were one in a million. And it can never happen again.

Looking at some of the stuff that was going on around that time with Ronnie Lane, it wasn’t just that Ronnie and I were making this album and having a lot of fun. It was, as you say, being introduced to studio musicians that I wouldn’t otherwise have worked with. The two guys that worked with the Stones as well, [saxophonist] Bobby Keys [and possibly trumpeter Jim Price] who played on our song Heart To Hang Onto, which is probably in my top three songs I’ve ever written. Listening to what they did on that, it’s just fantastic.

On the other hand, I didn’t go chasing after that buzz. And there’s a quick answer to why. Which is that, to this day, if I’ve got a free afternoon, where I want to be is in my studio, with my equipment, my laptop, my guitars, my pencil, my paper, my brain. And I don’t want to be fucked with by anybody else saying: “I can help you with this?” In fact, you fucking can’t help me, you know?

So what people like Glyn Johns have been able to do for The Who, and Chris Thomas has been able to do for me as a solo artist, is make me sound better. They haven’t been able to make me do a better job musically or creatively, it’s been a sonic thing.

Empty Glass [1980], aka your ‘first album proper’, was a very punchy, post-punk record. Did your choice of the Chris Thomas/Bill Price production team speak of an appreciation for their work with the Sex Pistols?

I didn’t even know Chris had produced the Sex Pistols, or that Bill Price had engineered them. I actually recorded Empty Glass in the studio the Sex Pistols had done Never Mind The Bollocks in. The thing about punk was that I felt they’d stolen my fucking manifesto.

I spoke with John Lydon recently and he had nothing but good things to say about you. He also gave the impression that the only problem you appeared to have with punk was that you couldn’t be as involved with it as you had been with mod.

That’s right. I’d have loved to have been a part of it as a producer, but I didn’t have time. I did try to produce Steve Strange and a few other spin-off bands from the post-punk, New Romantic era, but it didn’t go very well. But yeah, he’s right. And I like him very much. He’s so much better in the flesh than he might sometimes appear to be, and very clear-thinking. What’s happened to him with the loss of Nora is pretty extraordinary [Lydon lost his wife of 44 years to Alzheimer’s in ’23]. Here’s a guy, a typical Englishman who’s found the love of his life, and suddenly she’s gone. And he’s got many years left to live. He’s a lovely bloke, and very smart too.

Did it take you by surprise when suddenly, around 1976, a gaping generational divide opened up within the rock community itself, because at thirty-one you could have been forgiven for thinking you were still a relatively young man?

I was a contributor to that, unwittingly, with ‘I hope I die before I get old.’

And of course the first generation of rock bands were like canaries down a mine by then. Did you ever start to consider that maybe rock stars were like professional footballers, that a career in rock might yet prove to be a finite process?

None of us really knew what was going to happen. I knew that in my business, or at least in my dad’s business - my dad was still doing recording sessions and gigs into his sixties - and some of the artists we loved, particularly blues and jazz artists, were still touring in their fifties and sixties. It was as much about the audience as the bands. What was interesting with punk was the abandonment of the pop music system by the audience.

The Damned were a really good band. They used my studio in Isleworth, so I saw a lot of them in the early days. And was surprised that they were really good musicians, because you weren’t actually supposed to be. And that ‘you’re not supposed to be’ was part of the rebellion coming off the street. But the street was a very limited street. The King’s Road: a few fashion movers who took up the banner to begin with, hung on to it and refused to let go. Until death, in some cases.

But punk came from the audience and the industry, rather than the musicians. When you look at the average young musician, what they want to do is what they like to do, which is to make music, be famous, make a living. It’s very simple stuff. I mean, some people want more, and then when they get more they realise that that’s not the more that they wanted.

I wonder, for example, whether Mick Jagger really gives a fuck whether he has a plot on Mustique where he can spend Christmas, or whether he’d much prefer to come and have Christmas dinner with a bunch of friends in London. Because I know what I want. I want to be here.

I’ve been friends with Mick since very early days, and both of us have had aspirations to aristocratic living. But the interesting thing about London’s social scene at the moment is that there are some really great people, but there are also some absolute twats. And that’s always been the way. When you go to The Hamptons, there are some really great people and there are some twats. When you go to Mexico, great people, twats. Hollywood. It’s the same. Paris, Berlin… Go to any tribe or collective of beings, and if you’re willing to sublimate your desire to live however you want to live, take a chance and throw your chips onto the table and see how they land, that’s what happens. But it doesn’t always turn out the way you think it will.

The Sea Refuses No River, on 1982’s All The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes, seems like as good a jumping off point as any to ask about your lifelong affinity for the sea, a relationship I imagine predated you joining the Sea Scouts in 1955. When were you first entranced by the sea, what does it mean to you and why do you keep coming back to it?

It’s just a fact.

And the sea brings us to what you’ve previously referred to as the “music within the music”, which you apparently picked up on as a child, that remained with you, and lay at the heart of your Lifehouse concept enduring into 2005’s The Boy Who Heard Music and beyond.

That’s true, yeah. The idea music is about quantum physics as much as it is about notes. And of course the great big, white, pink - whatever you want to call it - noise that the sea makes in its undulations is an incredibly meditative thing. That said, it’s also a place to go for poetic corniness. A friend of mine is collecting pieces of old sailors’ sails and getting them to write on them before selling the finished pieces for charity. And I said: “I’ll give you a piece of a sail from one of my old boats, and I’ll write the lyrics to A Little Is Enough [from Empty Glass] on it”, and that’s just a string of corny, poetic extractions based on the sea.

One of my favourite novels when I first started to read seriously was Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo, and I realised then that if you’re in the middle of a really difficult story and you want a breather.

Does the sea’s ebb and flow have a music all its own that speaks to you? Quadrophenia’s overture-esque I Am The Sea gives the distinct impression of the album’s central themes being born of water, emerging from the sound of the sea. Maybe you’re drawn to the sea’s white noise because it facilitates the music that exists within your head.

I think that’s right. And I think that maybe the wind does it as well. What’s interesting is how sometimes when we’re trying to sleep we hear stuff that we don’t particularly want to hear. And if we allow ourselves to hear it, it can sometimes be an invitation to another sphere of thinking. Because the brain is an incredibly complicated organ that operates on so many different levels.

With Quadrophenia I was able to jack back into when I was a kid in the Sea Scouts, and I’d actually had this revelation on a boat on the Thames and heard this incredible music. It wasn’t the first time I’d done it, though. The first time was when I was about seven or eight.

I’d come back from living with my grandmother [at the age of six Townshend was sent to live with his “clinically insane” maternal grandmother, Emma ‘Denny’ Dennis, a traumatic experience that subsequently informed the creation of Tommy] and I’d spend time with my [paternal great-] Aunt Trilby. She had an old, out-of-tune piano, and I’d go and sit with her. She was really lovely and kind, whereas the grandmother I’d been with was unkind and horrible, so it was a place of solace for me. And I’d just play the notes on the piano over and over and over again, and it would spark music.

I thought she was hearing what I was hearing, until one day I did it for half an hour, and I came out of it in this incredible trance, and Aunt Trilby said: “That was lovely, darling.” I went: ‘No.’ What I’d heard was the most extraordinary music. And from that time on, until I was about fourteen or fifteen, I would often hear this extraordinary music. I can remember when I stopped hearing it - I tried to hear it, but couldn’t any more - it was about the time that I started to get pretty good at the guitar.

I’d had two or three years dealing with a really crap instrument but in the end managed to get hold of a decent Czechoslovakian guitar. From there I started to progress very quickly, and to put my imaginative-creative-brain shit into my playing. Trying to discover the music I was looking for from the guitar. I think that if we’d have had a piano, it would have been a very different journey for me. I didn’t start learning the piano until I was twenty-two, a bit late.

I don’t hear it any more. Though I do still search for it. When I go on Spotify, and I go for ambient music. I search for that music. There’s obviously other people who have a similar experience. And they’re searching for music, particularly in electronica, that makes sounds that are spatial and poetic in a kind of a modern, painterly, abstract way.

You’ve been fascinated by the potential of computers since art school, and now with the internet - which you kind of foresaw as ‘the grid’ in Lifehouse - reflecting the Meher Baba principle that ‘all are one’ - do you think the internet will eventually usurp all other lines of communication between artist and audience?

I don’t know that websites are any use any more. I really don’t. petetownshend.net isn’t my website. It’s a fan website. I’m actually talking about putting one together at the moment. My son Joseph and I have put together a small team, and we’re trying to make something out of what exists out there in the world of websites. A website’s just a bowl, a place where you dump stuff for people to access. And a place for links. So it can be whatever you want to make it, really.

Like everybody in my class in Ealing in 1961 [Townshend studied graphic art alongside Ronnie Wood at Ealing Art College until 1964], I was totally fascinated by the potential of computers, and we spent practically thirty years waiting for the computer that they’d promised us was going to arrive. What’s happened now is that I’ve actually lived long enough to find the computer overtaking me, with AI.

You very nearly articulated the entire concept of the internet with ‘the grid’, you may not have had the technology to realise it, but from Lifehouse through Psychoderelict it was always there, if ever so slightly out of reach.

Well, I like to try to find myself in a place where storytelling extends into vision. It’s just something that I’ve always done, and I’ve always loved visionary science-fiction writing, Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, people that foresaw the future. Asimov described the internet really well in one of his books in 1948, so there’s nothing new under the sun.

In your early years, a bottle of Remy Martin seemed to be an ever-present element of your creative process. Did sobriety initially affect your ability to work? And did you find that each time you went back on tour or record with The Who you faced a massive trigger moment?

Alcoholism and addiction is different for everybody, but the one universal thing is that for people who find alcohol to be useful for them, there’s a readily available pharmacy on every street corner. And you can go into some posh hotel in the middle of the day and say: (adopts posh accent) “Could I have a cognac, please?” Outwardly you think it makes you look big, but what you actually are is a despicable drunk.

But no, it didn’t divide up that neatly. I didn’t drink for eleven years from 1982, around the time I left The Who and worked as an acquisitions editor at Faber & Faber. I went back briefly to drinking in 1993 when Tommy was on in New York, and then I went into AA. Not because I was having trouble with not drinking, but because I wanted to be involved in something that would help me understand what the nature of alcohol was.

I’d run fucking rehabs as a functioning and as a dry alcoholic, because they say the only people that can help an alcoholic or drug addict is another alcoholic or drug addict. So it’s not like I was doing anything different. You know, a lot of the people that work at The Priory are ex-drug addicts.

Many creatives who drink convince themselves that without a drink they’d no longer be able to work, but it’s just one of those lies all addicts tell themselves in order to excuse, facilitate and maintain their addiction.

You’re right. And it is a medicine for some people, and those people for whom it’s an effective medicine are people you’d probably describe as definitive alcoholics.

There was some research done about twenty-five years ago with a peer group of forty people, two groups of twenty. One group were exposed to alcohol, the other given a placebo, and it turned out that when those that could be described as clinically alcoholic had alcohol introduced into their system they produced their own endorphin - endogenous opioids - while the ones that weren’t clinically classifiable as alcoholics didn’t have a desire to go back and drink.

In other words they could drink medicinally, but wouldn’t have this burning desire to drink just for the sake of drinking because they didn’t produce endorphin. So this suggests that those people that show up at places like AA for life are actually looking for something that will produce if not endorphin, certainly dopamine. Some sort of sense of comfort, of being safe, of being appreciated, that’s not on tap anywhere else, in a way. We know so much more now about how the brain operates, and the way that the brain and body’s neurotransmitters operate.

Reading your Who I Am autobiography, one of the things that stands out most throughout your entire story is that you’re a hopeless romantic who’s never happier than when in love. When you fall in love, you tend to fall completely in love. Maybe it would have been easier, as a rock star, to have been born more of a libertine, a swordsman, as it were.

Weirdly, it was only yesterday that I was telling a younger person that once you’ve thrown yourself into a loving relationship for a passionate moment, you have to learn to be mature enough to accept that it will not last. Then you have to test the relationship on the basis of it being a more fundamental, day-to-day experience.

I don’t know, maybe it’s because of stuff I experienced as a kid. I idealised my parents as this beautiful couple who had married young at the end of the war, had one of those post-war romances, then became disillusioned, split up, and I was the one that suffered. Then when they got back together again I was able to rebuild my life, but decided to rebuild my life in fantasy, to some extent.

I wouldn’t necessarily agree that I’m a lover, or obsessed with loving. It may be what came across in Who Am I, but it’s more that I’m a fantasist. Somebody that lives, and exists, by creative thinking, putting words or music on the page and examining it, seeing myself - or the world around me - reflected in it.

It’s an artistic function and it probably has come out of when I stopped drinking in eighty-two, I didn’t go to AA but I did go to see a Jungian therapist for three years. And one thing that came out of that was that it’s difficult for me to put a bridge between my storytelling side and my reality, in a sense.

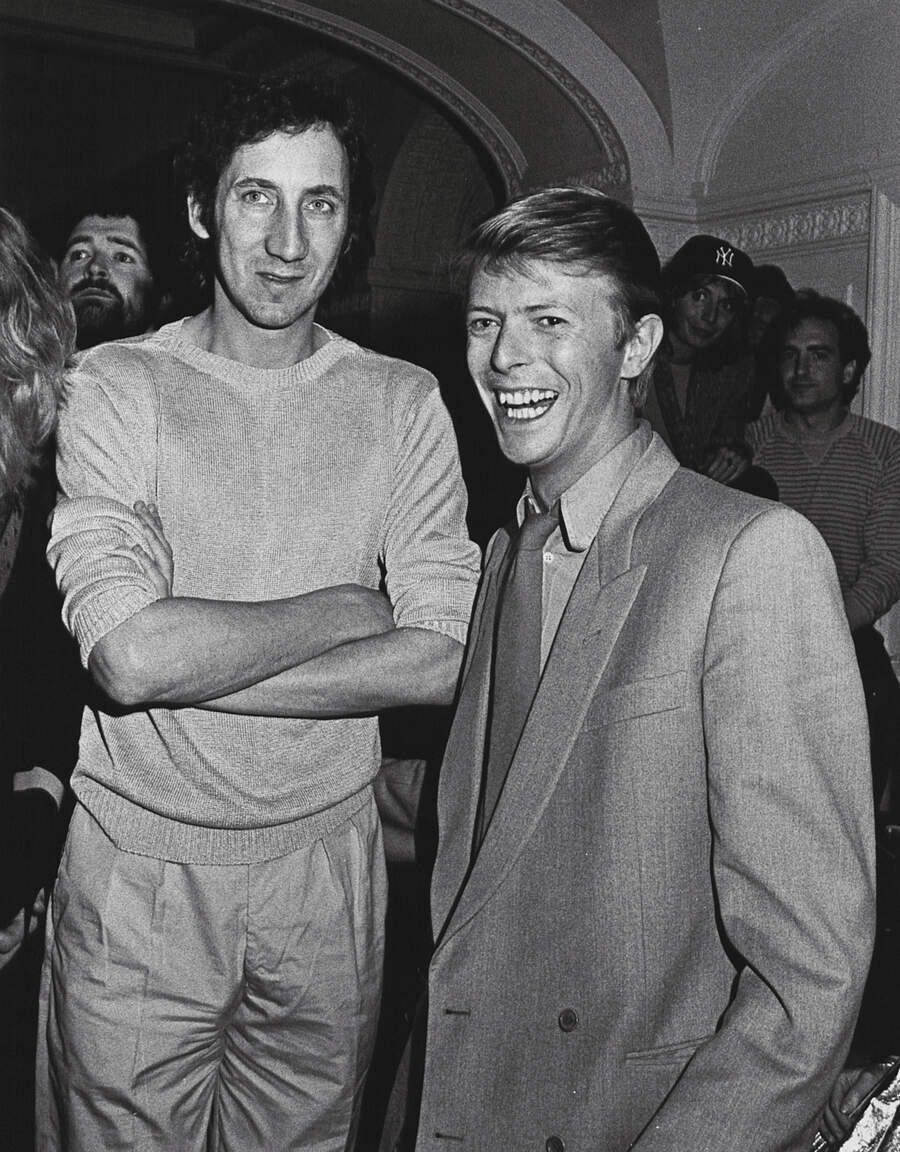

I’ve spoken to some other people about this, David Bowie was really interesting on it. I’d say to him: “There’s this David we all know, this ordinary David who likes art, music, a nice day out and a pretty girl, but who’s this other guy with fucking orange hair and make-up who insists on everything being strange, different and weird?” And we found we had something in common that was, possibly, a post-war phenomenon for young men. Maybe young women too, but certainly young men. A throwback to the experiences that our parents had.

In other words, who are the important creatures in Quadrophenia? Is it Jimmy? The girl he’s in love with? The Ace Face? The rock group that lets him down? The mod movement? No, it’s the mum and dad. Not because ‘your mum and dad will fuck you up’, although they probably will, but basically because they’re a post-World War II mum and dad.

The post-war era produced the most extraordinary artistic stuff in Europe. And The Beatles popped up in the middle of it, just four boys from Liverpool, very talented, nice looking, well mannered. And what is most extraordinary about them is that they didn’t last very long, but created this movement that did last a long time.

I see The Beatles - if I can use mod terminology - as the definitive ace faces of the British pop movement. That’s not appropriate to the Stones. The Stones were a different kind of rebellion, much more tangible, much more easy to understand, yobbos fighting to resist the establishment. The Beatles were part of the establishment, they embraced it and took it along with them. In fact they were very generous to the establishment.

If Yoko Ono was responsible for anything it was encouraging John Lennon into Gustav Metzger’s auto-destructive art. A different kind of way of looking at art, certainly for me.

I do like the idea that I’m a romantic, but I think I’m a fantasist, a slightly different thing.

Well, whatever you are, it seems to be working for you, Pete. So what’s next?

We don’t really know. I remember talking once about doing a one-man show and someone saying: “What’d be really interesting would be a one-man show with you and Roger.” So I said: “We’d just spend the whole time arguing.” And they came back with: “Yeah, that’s what would be good about it.”

One of the things Roger and I have to come to terms with, as we try as hard as we can to be friends and forgiving of our differences, is that there’s definitely an element among our sickest fans who want to be there on the night Roger knocks Pete’s teeth out. Again.

Pete Townshend The Studio Albums box set is out now via UMR.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.