“People would ask: ‘Is David Byrne a genius or a moron?’ I wanted to nip that ‘moron’ bit in the bud, so it was better to say ‘genius.’ The truth is somewhere in between”: The prog credentials of Talking Heads

The eccentric post-punk outfit certainly progressed with albums including More Songs About Buildings And Food, Fear Of Music and Remain In Light… but were they actually progressive?

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

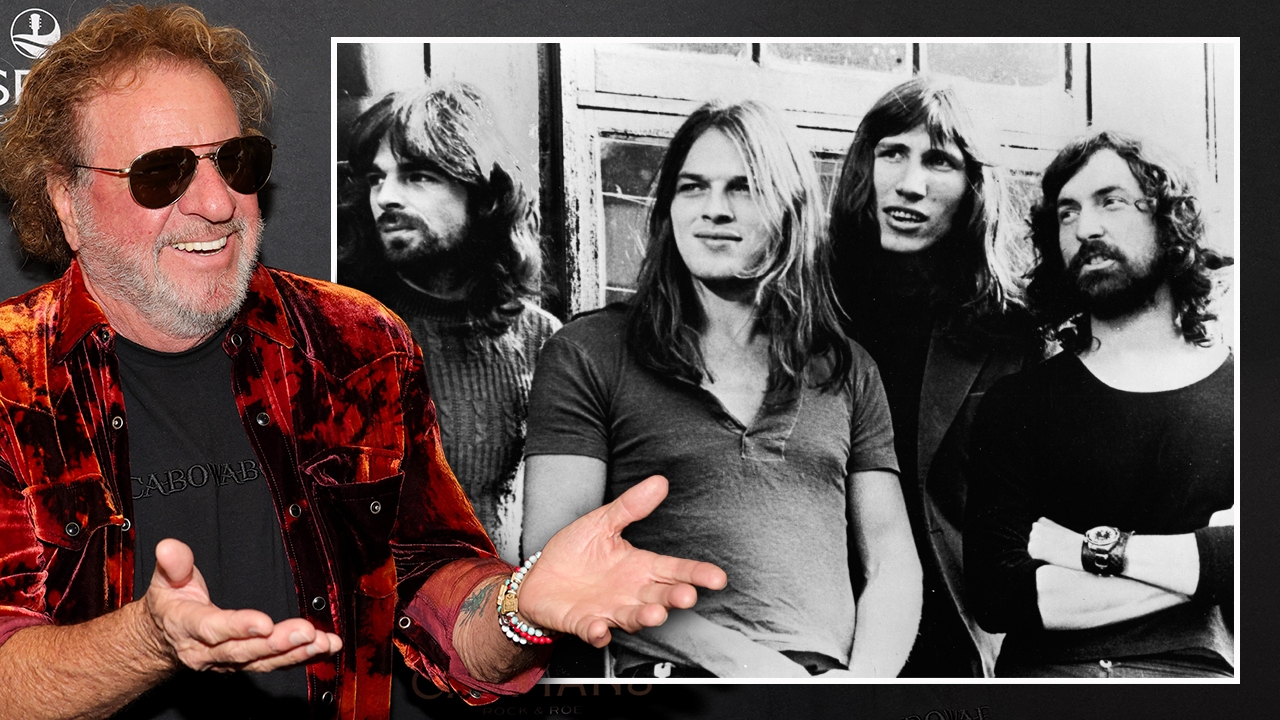

Declaring edgy post-punk funkers Talking Heads to be prog might seem like a bridge too far. But much of their work was truly progressive for those speed-addled times – not forgetting the input into their work by Brian Eno, Adrian Belew and Robert Fripp. In 2012 (long before the band members put their 80s differences behind them) Prog explored the question: how prog were Talking Heads?

“The most popular contemporary avant-garde group in America” is how Time Out described Talking Heads in 1980. In a way they were the Radiohead – named after a 1986 song by the band – of their day; their experimental sound and edgy, arty ideas attracting a huge audience.

Progressive? They certainly made astonishing progress, creatively advancing between albums, especially the three they recorded with producer-catalyst Brian Eno. In fact, so giant were the leaps they made that Simon Reynolds, in his 2005 book on the post-punk era Rip It Up And Start Again, was moved to compare them to The Fab Four.

“The trilogy of records Eno and Talking Heads made together recalls the runaway evolution of The Beatles across Rubber Soul, Revolver and Sgt Pepper’s,” he wrote of More Songs About Buildings And Food (1978), Fear Of Music (1979) and Remain In Light (1980). These were albums that variously featured, alongside the erstwhile Roxy Music chrome dome, Bowie/Zappa guitarist Adrian Belew, world music pioneer Jon Hassell and King Crimson majordomo Robert Fripp.

Talking Heads have had numerous appellations ascribed to them, from new wave and dance-rock to art disco and brainiac pop – but how about progressive funk? It seems to suit the cerebral nature of their highly rhythmic music.

“‘Progressive funk’?” muses Chris Frantz, co-writer of many of Talking Heads’ best-known tracks including Psycho Killer and Life During Wartime, and drummer from their inception in 1975 after his previous band with singer David Byrne, The Artistics – formed when the pair were at the Rhode Island School of Design – ran out of steam. “That’s not bad.”

“They used synthesizers and all kinds of new technology,” says Belew, who appeared on the Heads’ fourth album, and spent a year in their touring line-up. “But were they prog? When I think of the term ‘progressive’ I think of epic things like Yes and King Crimson. ‘Progressive’ to me means something ahead of its time, moving forward... so in that sense, sure.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Frantz remembers prog’s golden age. He was at art school in 1971, where two records dominated student dorm stereos: Neil Young’s Heart Of Gold and Yes’ Roundabout. “You’d walk down the hallway and hear one and then walk a bit further and hear the other,” he laughs.

People on Facebook tell me every day the music changed or saved their life. I never tire of it

Chris Frantz

He acknowledges the prowess of the prog musicians. “I have a great deal of respect for those guys and their musical chops,” he says. He doesn’t believe, however, that Talking Heads were in the same league in terms of pyrotechnical ability.

“I would say the most musically accomplished member was Jerry Harrison. He was a great keyboardist and guitarist. David was an excellent rhythm guitarist and Tina a wonderful bassist. As for me, I’m a pretty good backbeat player, but if you asked me to do a drum solo I might just give you the stink eye.”

Whatever their shortcomings on their chosen instruments, there is no doubt that the four players, when they got together in the studio with Eno, made for an awesome, inventive unit. Frantz has grown used to receiving accolades on behalf of this highly influential outfit, one that has become synonymous with dark, intense dance music that isn’t necessarily designed to be danced to. “People on Facebook tell me every day the music changed or saved their life,” he says. “I never tire of it.”

The first time most people heard Talking Heads was 1977, when the funk noir four – Byrne, Frantz, his girlfriend and later wife Weymouth plus former Jonathan Richman’s Modern Lovers member Harrison – emerged out of New York’s CBGB scene. To say that they stood out next to their peers – the burgeoning New York punk/new wave milieu that included the Ramones, Suicide, Television, Blondie, the Patti Smith Group and Richard Hell’s Voidoids – would be to do understatement a disservice.

Musically, as evidenced by their 1977 debut album - titled, with typical neatness, Talking Heads: 77 - theirs was a clipped, bright but weird pop that suggested a warped mix of African rhythms and bubblegum melodies with the spikiness of punk. Lyrically, too, this was virgin territory: songs that seemed to celebrate conformity and ran counter to rock’s usual credo of rebellion and degeneracy. Talking Heads looked and sounded clean-cut.

“We were inspired by Roxy Music,” admits Frantz of their formative sartorial period. “We didn’t have the funny outfits, though. When I see those pictures of Paul Thompson in that leopard skin suit, and Eno... Eno was really out there.”

Talking Heads were the diametric opposite of Roxy’s retro-futurist amalgam of styles. Frantz explains how the Heads came up with their defiantly simple preppy early look.

“I always say it was the clothes our moms gave us for Christmas,” he laughs. “When we arrived in New York, The New York Dolls were still going and there were a lot of people in bands wearing platform shoes and satin trousers. We thought: ‘We can’t dress like that, we’ll look and feel ridiculous.’ So we decided to go with button-down shirts or Lacoste polo shirts. That seemed to work really well for us.”

We came from a place where ideas and conceptualisation were almost more important than craftsmanship

Tina Weymouth

They might have looked like the most unprepossessing students, but there was an intensity to their frontman that lent the band a so-normal-they’re-disturbing air and made Psycho Killer, their most famous song, seem virtually autobiographical. Or, as David Byrne himself put it in an interview in 1992: “Looking at old videos of us, it’s like three normal kids backing up this maniac.”

Even in an era that threw up Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious, Byrne was unusual, appearing to teeter on that fine line between genius and madness. Discussing it today, Weymouth says: “People would ask: ‘Is David Byrne a genius or a moron?’ I wanted to nip that ‘moron’ bit in the bud, so it was better to say ‘genius’. The truth is somewhere in between.”

Looking back, she says: “We had fun making those Talking Heads records – they were rarefied times.” She doesn’t accept the brainiac tag, asserting: “our music was emotionally profound.” She adds: “People say we were clever, and it’s funny – it’s also quite mistaken! Compared to Stephen Hawking we’re just midgets. Imagine if we had A Hawking Heads – that would be something.”

Yet she concedes that Talking Heads were big on ideas. “We’d been to art school – not that we were effete snobs – but we came from a place where ideas and conceptualisation were almost more important than craftsmanship.” The band’s experimental approach saw them make, she decides: “science fiction funk.

“Everything we did was texturally entirely different,” she asserts, “because we had this interesting mix of people: Chris came from the steel town of Pittsburgh and understood that raw black American sound. Then there were myself, David and Jerry who had been exposed to a lot of European classical music. So when you combine the African-American rhythms with that European melody you get Talking Heads.”

Their sci-fi funk process involved Eno’s use of oblique strategies, including the random chance cards he had brought to bear on the sessions that produced Bowie’s Berlin trilogy. “They were fun,” recalls Frantz. “One said: ‘When in doubt, be quiet.’”

The Fear Of Music sessions involved a different kind of oblique strategy: Eno and crew sat in a truck outside Weymouth and Frantz’s loft while cables ran upstairs to where the band performed the songs. Was that weird?

“No, it worked out just fine,” says Frantz, who enjoyed making a record that soon became synonymous with paranoid punk-funk: from its terse song titles (Mind, Air, Paper, Animals, Drugs) to its jittery rhythms, it brought to mind Anthony Perkins circa Psycho down at Studio 54. “We had a good time - a good time being paranoid.”

That would have been very destructive for the band. You couldn’t replace David Byrne, and I wouldn’t have wanted to

Adrian Belew

For the follow-up, arguably their finest foray into (out of this) world music, the band accommodated extra musicians such as keyboardist Bernie Worrell and Belew. Although Frantz talks up those Remain In Light sessions now, at the time there were rumours of dissent in the ranks as the other three found themselves increasingly treated like Byrne’s backing band.

Did Belew, an outsider, detect animosity? “Not in the studio, because Chris and Tina weren’t there when I played my parts,” he replies. It was on tour later that he was “privy to the in-fighting and questions as to who should be credited for what.”

“I just tried to remain neutral and have fun,” he says, “which it was, a lot of the time.”

Weymouth recalls “some temper tantrums” as relations broke down. “David had a lot of those when he got to be a star,” she reveals. “Fame overwhelmed him.” But then, as she admits: “It wasn’t a sane time in our lives.”

Is it true that Weymouth asked Belew to replace Byrne? “Yes,” says the guitarist. “Chris and Tina raised the question. But that would have been very destructive for the band. You couldn’t replace David, and I wouldn’t have wanted to. It came out of Tina’s anxiety.”

There wouldn’t be another Heads album until 1983’s Speaking In Tongues, and thereafter only two more: 1985’s Little Creatures and 1988’s Naked (that is, unless you count 1986’s pseudo-soundtrack True Stories as an official Talking Heads release). They all saw a scaling back in terms of ambition and experimentation, but they did make the band more popular than ever as songs such as Road To Nowhere and Burning Down The House made them early stars of MTV.

They also saw Byrne and the rest become increasingly estranged from each other as it became apparent that he intended to go solo. “Was there tension?” wonders Frantz. “Only because David had plans outside Talking Heads and he wasn’t keeping us abreast of what they were.”

One sensed mutual antipathy seeing the four together onstage to receive that Hall of Fame induction in 2002. Have they spoken since? “Barely,” says Frantz. “I would be happy to sit down and talk to David, but he’s not a social guy. His preferred method of communication is email.” It’s a shame, he says, because they started out as such great friends. “We did pretty much everything together, but as the band became more popular David grew more distant.”

Is it all Eno’s fault? “No,” he replies. “It’s just one of those things. We had a wonderful chemistry, but nothing lasts.”

Adds Weymouth: “We just have to be glad there was no loss of life – nobody was killed in the creation of a Talking Heads record.”

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.