Remembering that time Vanilla Ice made a metal album

The bizarre tale of how ex-superstar rapper Vanilla Ice and Ross Robinson teamed up for the universally reviled nu metal album, Hard To Swallow

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The 90’s certainly were a wild time. Far from the derelict landscape for metal that some would have you believe, the insane success of nu metal in the late 90s represents a commercial high for the genre. Although it was not to say that this level of interest in metal was without its problems or embarrassing moments for our scene. High on the success of Korn, Deftones, Coal Chamber and Limp Bizkit, all of whom were becoming legitimate rock stars around the time, one of the first half of the decade’s most least credible musicians would jump upon the nu metal bandwagon. The results were bizarre, and over two decades later we’re still trying to work it all out; why and how did Vanilla Ice end up making a record with some of the most credible names of the period?

To understand just why this is so weird, we first have to put Vanilla into some kind of context. Robert Matthew Van Winkle was born in Texas in 1967. He loved two things as a kid: music and motocross. As a young boy, it was motocross that Van Winkle wanted to pursue as a living, and he might well have done so. He won three championships before breaking his ankle in 1985, an incident that curtailed his career. Motocross's loss was very much music’s loss.

To pass the time as his ankle healed young Robert would beatbox and breakdance at the mall with his friends, acquiring the nickname Vanilla Ice due to his love of hip hop and a dance move he called ‘The ice’ at the time. He soon swapped his attention from motocross to music and got a job dancing and beatboxing at the City Lights nightclub in Dallas after winning an open mic competition. There he supported the likes of N.W.A., Public Enemy, 2 Live Crew and… ahem… Paula Abdul.

Vanilla signed his first record contract in 1987 and released his debut single, a cover of Play That Funky Music by Wild Cherry in 1989. The single was a decent enough success, reaching number 10 in the UK singles chart, but it was when DJs started playing the b-side, Ice Ice Baby, that Vanilla Ice really took off. The single proved hugely popular with radio listeners and was rush released as a standalone single just prior to Vanilla’s debut album being released.

We don’t need to tell you that Ice Ice Baby was a success, do we? It went on to become the first ever hip hop song to top the US Billboard Hot 100, it went to number one in seven other countries, top 10 in 18, It has gone Platinum in four countries, gold in another four and has sold over 1 million copies in the US and 600,000 in the UK alone. A week two weeks later and Ice’s debut album To The Extreme was released and went on to sell 15 million copies worldwide, spending 16 weeks atop the Billboard Top 200 and becoming the 20th best-selling album of the decade in the US.

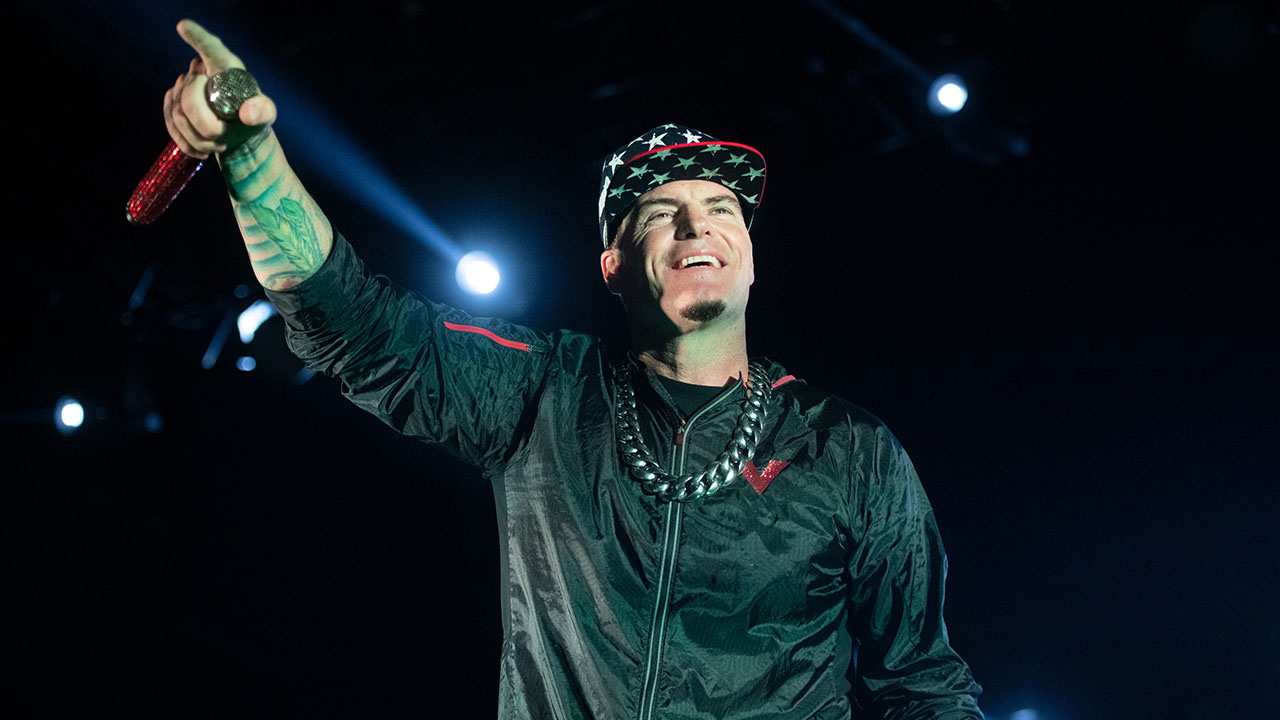

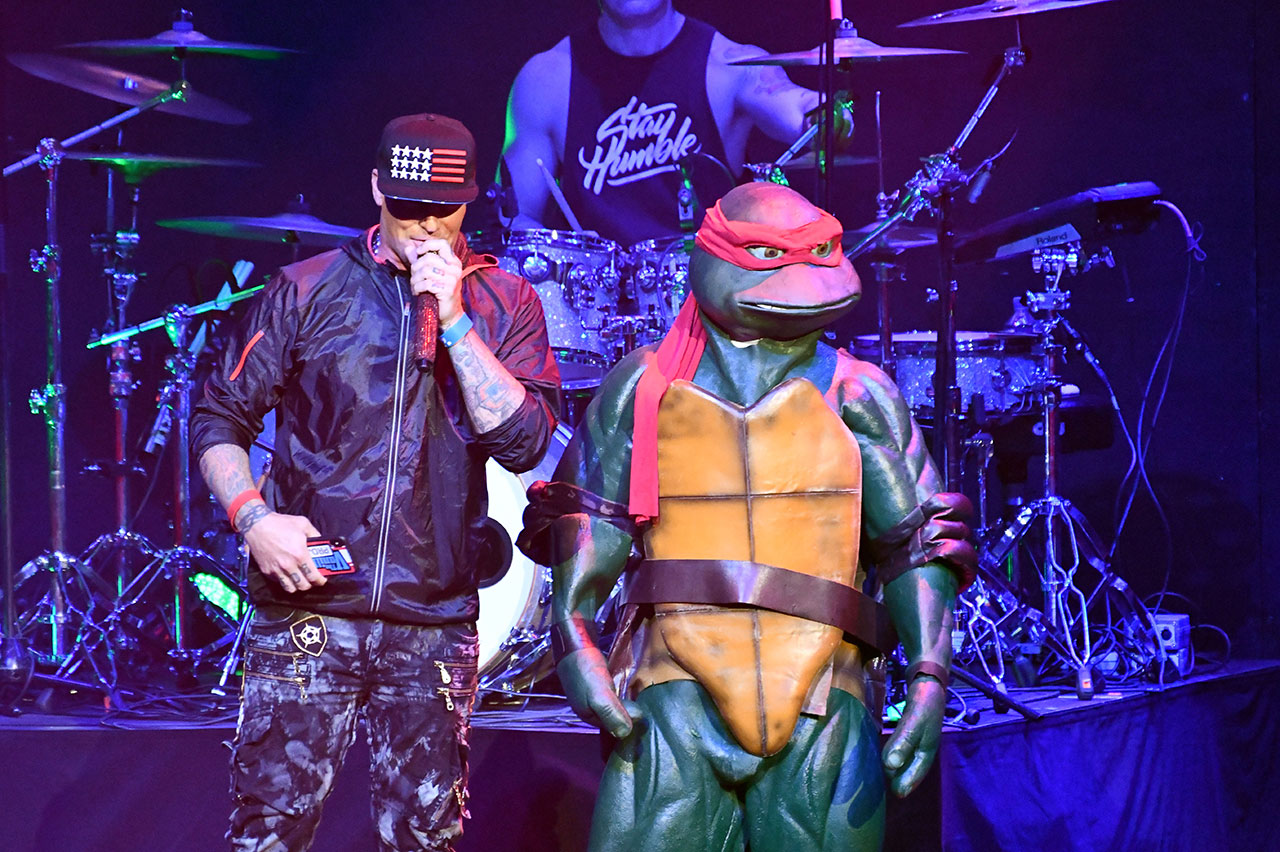

Vanilla Ice was now a superstar. He dated Madonna, he appeared in, and provided the lead single for, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 2 movie (very much The Avengers of their time) and he even got a movie of his own, Cool As Ice.

But the backlash had very much begun. As he toured the record relentlessly, he picked up a Golden Raspberry Worst Actor award for his role in Cool As Ice, he was mockingly portrayed by Henry Rollins in the video for 3rd Bass’s Pop Goes The Weasel – a song about hip hop being infiltrated by pop chancers, and his live album follow-up Extremely Live only peaked at number 33 on Billboard and was called “One of the most ridiculous albums ever released” by critic David Browne in Entertainment Weekly.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Merely a year after becoming one of the biggest stars on the planet, Vanilla Ice was yesterday's news, the butt of a million jokes, and, save for 1994’s non-charting Mind Blowin’ album and a short-lived grunge project called Pickin Scabz, who never released any music, he basically vanished.

During this period he formed a destructive drug habit, raced jet ski and had a failed suicide attempt. At his lowest ebb, he formed an unlikely friendship.

Ross Robinson was one of the hottest music producers on the planet. His work on Korn’s 1994 debut album and Sepultura’s Roots in 1996 had revolutionised the sound and approach of heavy music to the point that, by 1998, his mix of mud-thick guitars married to deeply personal lyrical expression was the most zeitgeisty sound on the planet. He also loved motocross.

In an interview with Well Rounded magazine from 1998 Vanilla tells how his Republic Records founder Monty Lipman introduced him to Robinson’s work when Ice was considering making a new, and different, kind of record. “I wanted to express myself in a very intense way, and there was no way that was going to happen with a drum machine,” he told the Iowa State Daily in 1998. “basically I’m bored with drum machines and samples and stuff. With a band, they can build that energy around me.”

Impressed with the producer’s work, Vanilla invited Robinson to his house for a meeting: “Ross walks in and sees my motocross trophy and he’s a motocross racer himself,” he said. “We were clicking right off of the bat, we had something in common. He was like ‘Yeah man, I’d really love to do your record.’. I flew to LA right away and within a month and a half we had the album finished, completed.”

It’s easy to see what Vanilla would be getting from the union, but for Robinson? Less so. But the producer is a notoriously unpredictable character, and the more he was told not to do it, the more he was adamant that he wanted to work on the album, telling The New York Times, “People kept saying to me ‘It might hurt your name, it might hurt your reputation’. I said, ‘I’m doing it then.’ It’s the most punk rock thing you could do.”

Robinson obviously saw something bitter and broken in the former superstar, and believed his trick of extracting pain and deep-set psychological trauma from artists would translate into something genuine. He immediately began to mine Ice’s past experiences to find some inspiration for the record.

"I was like Jerry Maguire back then," Ice told CNN at the time as he looked back upon his early career successes. "I was like, show me the money. That's over now. A lot of the criticism led to very bad depression, but I learned that life is not about material things or how many records you sell."

The narrative of ‘I used to be famous and love money… but everyone criticised me!’ is hardly as compelling and relatable a starting point as the likes of Korn’s Jonathan Davis was expressing. But this was the late 90s, and no matter how trivial the trauma, if it was there, it was fair game to be exploited in your music. So, Robinson further encouraged Vanilla Ice to wallow in his own self-pity.

“It wasn't intended to be so dark.” Ice continued. “I opened up to Ross and I told him a lot of things that happened to me in the past, it was like, really deep conversation, and he was like, ‘You should write about that.’ And I was like, ‘dude!’, I didn't want people to judge me for that. But he was right. This record was like total therapy. I had to tap into these fucked up moments in my life, I’m free now.”

As news began to circulate that the metal world's hottest producer and the washed up, faux hip hop white boy were working together, so the rumours of the album began to grow. It was said that everyone from Lenny Kravitz to Korn were going to be appearing on the record, something Korn’s management immediately denied, and, in the end, we just got Jimmy Pop from The Bloodhound Gang and Amen’s Casey Chaos.

Vanilla was keen to embrace this new style of music, despite claiming he had never heard of Limp Bizkit until he met Robinson, and that the meld of rap and rock totally organic, “I wanted to make the record as real as I possibly could and do it my way,” he explained. “I'm not trying to be like any Korn or anything like that. In fact, I didn't even listen to them or any of them. I knew who they were before I made this record. It's just we have the same producer, and some of the guitars between that and Limp Bizkit are gonna sound similar. That's what happens when you've got the same guy producing them.”

The sound that is produced on the album actually comes from a fairly credible source. Robinson was able to use his position in the metal scene to put a band of significant quality together to back Vanilla, this included Amen drummer Shannon Larkin and guitarist Sonny Mayo, Limp Bizkit guitarist Wes Borland’s brother Scott of Big Dumb Face fame on keyboards and future Puddle Of Mudd bassist Doug Ardito. Larkin would later claim to Modern Drummer magazine in 2006 that he was “Proud of that one. That was a killer record. Producer Ross Robinson is very demanding when it comes to drums in the studio. Everything had to be 110% for that guy, and I love him for that."

Prior to the release of the record, in his CNN interview, Ice made it clear that this was not a commercial cash grab, or a case of a star from another genre jumping on a more popular bandwagon. “I feel much better. I rate the success by what I got out of it, no matter if it sells one record or a million.”

Which is lucky, because, when released on the October 20, 1998, Hard To Swallow sold significantly less than a million copies. In fact, in stark contrast to his debut, it failed to chart on either side of the Atlantic, hasn’t been certified in any country and was met with a scathing critical response, with Rolling Stone stating that “Nothing can redeem Ice’s whack boasting.” New Times magazine called it “Stupid, exploitative, derivative rap metal by the man who once did nearly irreparable damage to hip hop,” and in the years since has appeared in Q’s list of the top 50 Worst Albums Ever, The AV Club’s list of the Least Essential Albums of The 90s and Maxim’s Top 30 Worst Albums of All Time list, before it sank without a trace.

Ice was quickly dropped by his label, never worked with Robinson again and the rest of the metal community did their best to distance themselves from him. But, to his credit, he persevered and released a half-rap, half-metal follow-up double album called Bi-Polar in 2001, which even features a voice message from Robinson, telling of a recent motocross accident he had during his spare time whilst working on Slipknot’s Iowa album.

But ever since those days it’s been a career of nostalgia circuit appearances, reality TV shows and duets with Jedward for Vanilla Ice.

Listening back to Hard To Swallow today, it’s easy to see why it never really happened for Vanilla Ice in the metal world. The music on the record is competently played, although, as was standard at the time, it’s incredibly rudimentary with very little in the way of expert songwriting. But the man on the mic is definitely the problem with this album. Be it a rough’n’ready, beefed up but far less catchy version of Ice Ice Baby, named Too Cold, that really doesn’t work, the seedy The Horny Song where Ice makes what can only be described as… umm… sexy noises, as he paints us some very unnecessary pictures of his bedroom antics or the eye-rollingly bad ‘I was a massive pop star but it made me so miserable’ whining on S.N.A.F.U., there are very few times where he doesn’t all but ruin what could have been an acceptable, if unremarkable, nu metal number.

But it’s when he goes full Rastafari patois on opener Living, complete with a Cool Runnings-esque Jamaican twang, that your jaw really hits the floor. It’s tempting to suggest that Vanilla Ice single-handedly invented cultural appropriation just by attempting that accent alone. It’s a low point on an album filled with very few high points. Twenty-three years on and, yeah, you won’t be shocked to learn that Hard To Swallow has aged pretty badly.

Vanilla Ice and heavy metal; he collaborated, we listened, we’re glad he stopped.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.