Mud, mayhem and four-hour Grateful Dead sets: The chaotic story of Weeley and Bickershaw, the early 70s festivals that time forgot

Not every festival could be Woodstock or the Isle Of Wight

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Woodstock, Altamont and the Isle Of Wight are etched into the history books as the most famous festivals of the late 60s and early 70s. But there were plenty of others – and some of them are notable for the wrong reasons. The UK’s Weeley and Bickershaw festivals were two of them, whose extreme weather, pitched battles between Hells Angels and security and general air of chaos put them closer to Armageddon than the Summer of Love. In 2007, writer and musician Mick Farren – who attended both – looked back at his time on the front lines.

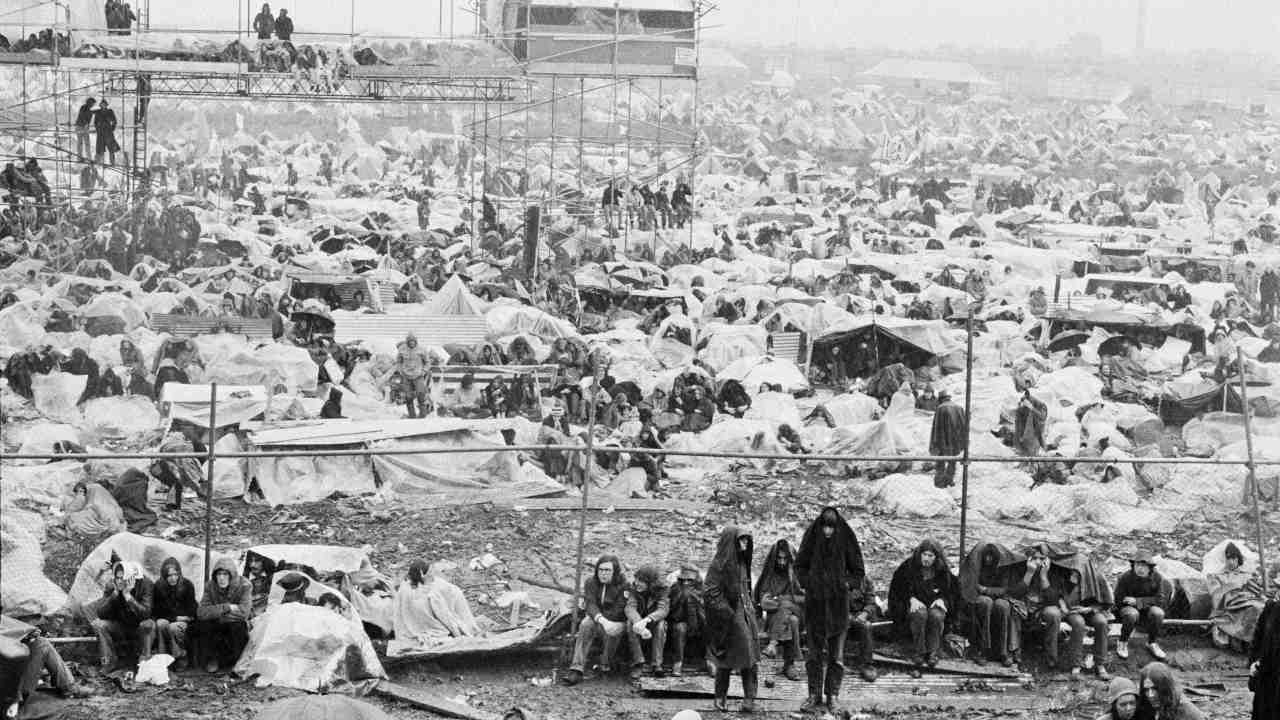

Mud-covered figures waded and stumbled in a viscous, calf-deep mire. Somewhere across the waterlogged wasteland the Flamin’ Groovies were pounding out Teenage Head as the rain fell relentlessly. One figure in the muddy throng was distinguishable by the way he was working two flashing electric yo-yos at the same time. He was a wandering rock festival hippie yo-yo vendor, and I suddenly and irrationally wanted one. “How much for a yo-yo?”

I don’t remember his reply, but it would have made no sense. I’d been in rain and mud for 48 hours. Money had ceased to have any significance. If I had any it was soggy pulp in my pocket. What I did have, however, was alcohol. Earlier in the day my companions and I – freaks from underground papers IT and Oz, plus Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies – had made a booze run to town. The yo-yo vendor was now eyeing the bottle of Bacardi in my hand.

“Swap you a yo-yo for a hit of rum?” I accepted readily. Such was the way at an old-school festival.

This encounter was at the Bickershaw Festival, staged in a badly drained field with a pond in the middle, somewhere outside Wigan in May 1972. The rain had teemed down for three days, until the site resembled the Western Front in World War I, and it only stopped raining when the Grateful Dead began to play.

Now that rock festivals are highly organised garden parties at former holiday camps and converted airfields, with star performers and creature comforts, it’s hard to imagine how, a quarter of a century ago, they could have been such debacles of mayhem and chaos that they resembled rehearsals for the apocalypse.

Much has been written about Woodstock, Altamont and the Isle of Wight – the good, the bad, and the ugly of the early music fests – but other shows have been all but forgotten with the passage of time. Which is a pity because many were equally bizarre events, especially when the aims of their promoters ran head-first into the reality of inflicting a large tent-town on some unsuspecting rural geography and then filling it with a temporary population of rock’n’rollers determined to behave with high illegality.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The Bickershaw Festival was one prime example of old-school rock-festival anarchy in the UK. Another was the Weeley Festival that took place a year earlier, just outside Clacton, in August 1971. The Weeley Festival was the diametric opposite of Bickershaw. The weather was hot and dry, and – instead of slowly sinking into a sea of liquid mud – Weeley erupted into raging grass fires, and violent confrontations between the festival’s security men and outlaw motorcycle clubs.

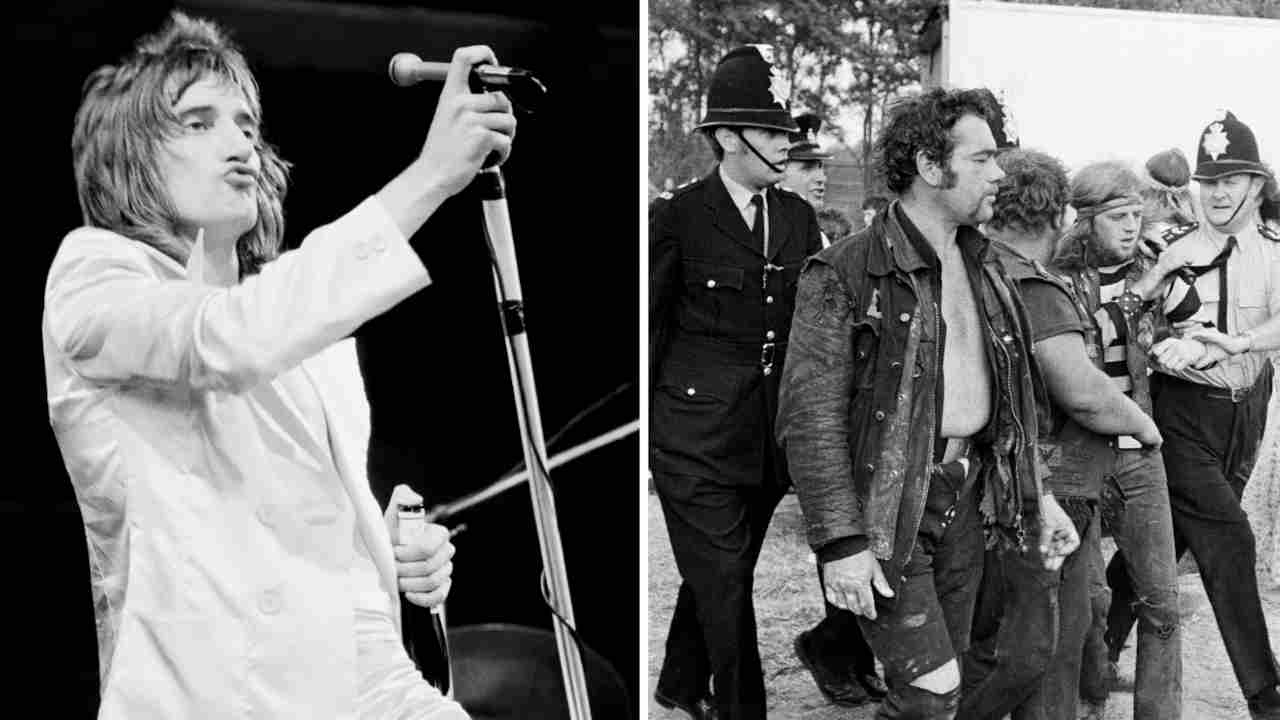

Both events looked good on paper. Each featured a stellar bill: the posters for Weeley boasted the Faces, T.Rex, Status Quo, Rory Gallagher, King Crimson, Mott The Hoople, Mungo Jerry and the Pink Fairies, while Bickershaw offered its drenched and mud-covered crowd the Kinks, New Riders Of The Purple Sage, Dr John, Hawkwind, Country Joe McDonald, The Incredible String Band, Donovan and Wishbone Ash, plus an historic set by Captain Beefheart and the specially reassembled Magic Band, and the first four-hour set by The Grateful Dead ever seen by a British audience. The promoters guaranteed reasonably priced food and drink, a free camp site, and adequate toilet and washing facilities. As it turned out, however, these were the least of anyone’s worries.

To say these promoters were inexperienced is hardly fair. In the early 1970s nobody really knew how to run a huge open-air rock event. Blackhill Enterprises – who presented the free concerts in Hyde Park – had become adept at promoting shows that lasted just a few hours in the afternoon. A three-day event was a very different matter, and crucial factors were inevitably overlooked.

The promoters of Bickershaw were a collection of local businessmen, led by TV presenter Jeremy Beadle, and they had either failed to ask some very important questions. Was May in the north of England really warm enough for an open-air festival? Was a site with standing water a suitable place for a rock festival, and what might happen if it rained? At Weeley, only one question really needed to be asked: what possessed the local Round Table – who freely admitted they had never organised anything bigger than a donkey derby – to believe that they could run a major rock festival as a charity event?

One crucial error was that the Round Table neglected to mow the site’s long grass before erecting the stage and preparing the camping ground. By the time the crowd settled in they were ankle deep in bone-dry tinder and fire was a clear and present danger. When the underground press gang from IT and Oz arrived a number of parked cars had exploded and burned. The Pink Fairies, who had arrived earlier, told lurid stories of smoke, flame and gasoline explosions. And if that wasn’t bad enough, the Hells Angels and the security goons were about ready to go at it.

Seemingly, the outlaw bikers had been doing some effective fire control, but when they started to assume a quasi-official status they ran head-first into the festival’s real security. Throughout the course of one day, spasmodic fights broke out, until the bikers were cornered in a backstage area. A report in the underground paper Frendz described their last stand: “A vigilante committee formed consisting of concessionaires, security men, (very heavy, out of work commandos etc) and stage hands. Armed with monkey wrenches, clubs, sledgehammers, they marched on the Angels. Three were taken to hospital unconscious, at least one with a fractured skull, many more badly beaten up. Reports indicated that one of the Angels had died in hospital.”

With the bikers vanquished, the security men acted like an occupying army. Four of them, hefting nasty cudgels, approached the truck and the MASH-style tent where the Pink Fairies and the IT/Oz crew were camped. “You lot are a bunch of Angel lovers, right?”

Not wishing to be duffed up, we did our best to look mystified, but it was counter-culture common knowledge that the Pink Fairies, Hawkwind and most of the underground press were on good terms with Crazy Charlie and the Hells Angels London chapter. Just to compound matters, Paul Rudolph, the Fairies’ guitarist, had been roaring round the campsite all afternoon on a Triumph dirt bike. Mystification appeared to work, though. Security didn’t seem to consider us a threat and moved on with words of contempt.

And yet, while these violent dramas were being played out on one part of the site, the punters across field knew little or nothing about it, and were only concerned that King Crimson performed magnificently; that the Faces were almost too drunk to do it; or that Marc Bolan, by sheer force of will, won over a hostile crowd outraged by his recent pop-star success. Although Marc was accused of a lot in his short life, lack of bottle was never a charge. Bolan faced down maybe 50,000 pissed-off rock fans and politely requested that they “make love somewhere else”. The crowd faltered for a moment. “What did he say?” Then realisation dawned that this was elf-speak for “fuck off”. A ragged cheer spread: Marc had gained some major rock’n’roll credibility.

Later, when the stage had shut down for the night, strange bellows rent the air. “Wally!” The shouts came at random from all parts of the field. “Wally! Wally!” Legend insists that Weeley was the birth place of this weird practice, a claim supported on www.ukrockfestivals.com by a post from Weeley attendee Brian Nugent: “The real Wally was sitting just in front of me, and his friends were trying to get him back after a visit somewhere. They started shouting his name and pretty soon everyone joined in.” A character called Wally Caton, however, fervently disputes this: “I was at the Isle of Wight festival in the late 60s, my friends were looking for me and called my name. And soon after, everybody was shouting ‘Wally!’ I never did meet up with my friends, but the guy sitting in front of you was not the true Wally, I am.”

No one, however, was shouting “Wally!” at Bickershaw. The tribal cry would have been lost in the downpour. Shortly after the encounter with the yo-yo salesman, I had bluffed my way onto the stage, to shelter from the storm and get close to Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band. Looking out from the stage and into the crowd, the sheets

of rain were, to say the least, weird – like a massive aquarium with the water on the outside. But the Captain was the Technicolor moment in a sodden and monochrome weekend. The Magic Band were nothing short of Venusian, playing warp-power, pan-galactic blues and performing an unearthly conga line as they did it.

Mike Plumbley has a complete Bickershaw diary on www.iowrock.demon.co.uk, and he confirms my own damaged memories: “A be-caped and bearded Captain made it out to centre-stage and began to snarl with all the venom of Howling Wolf moanin’ at midnight. Between verses the Captain wailed mouthfuls of south-side Chicago harp. Behind him the band’s choreographed slapstick dance veered somewhere between Elvis Presley and the Marx Brothers.” I just accepted the cosmic aptness of encountering the Captain in a Lancashire downpour.

For most of the drowned masses, though, the Grateful Dead were the stars of Bickershaw, and Deadheads’ compulsive archiving has given the festival more prominence in rock history than it maybe deserves. Bickershaw is also preserved on a 2007 DVD from Ozit Morpheus Records which clearly shows how the sun actually broke through when the Dead began to play. I don’t believe, even in 1972, the Grateful Dead could control the weather, but I found the coincidence unsettling.

My henchman Boss Goodman, on the other hand, was energised. “Wanna see how close we can get to the Dead?” he asked. I nodded. It only seemed right. I had done the same to see Beefheart.

Between us we had amassed a mess of backstage credentials, and he worked his way past all checks and challenges, until the two of us reached Goodman’s ultimate objective and were squatting like mud-men directly behind Jerry Garcia’s speakers. To do the same today would be impossible, when musicians are as protected as presidents, but this was the era of glorious chaos. Well into a swirling solo, Garcia spotted us. He smiled wearily. He had seen it all before.

Between songs, the Dead’s Bob Weir confirmed the band’s populist knack of keeping up with local politics: “I understand that that bill they were trying to push through the legislature here was defeated.” Garcia and most of the crowd didn’t understand, and Weir explained: “The Night Assemblies Bill. It was defeated last night. It means that you guys can go ahead and have all the festivals you want.”

The Night Assemblies Bill was a parliamentary response to events like Weeley and Bickershaw that would have cripplingly over-regulated open-air concerts during the hours of darkness. Organising any festival would have become impossible. The Bill’s defeat was welcomed in the rock world.

The huge and anarchic old-school festivals were a testimony to the power of rock’n’roll, and they demonstrated just how much discomfort and possible bodily harm people were willing to tolerate in order to hear music. Legends claim that a teenage Joe Strummer and a young Elvis Costello were at Bickershaw, and the show inspired both to start their own bands. The truth, however, was that by 1972 these Armageddon-style festivals were on their way out, and, predictably, it was all down to money. The promoters of both Weeley and Bickershaw lost fortunes, and investors for more of the same became impossible to find.

And yet Weeley and Bickershaw have their place, if only as tales of ancient hallucinating glory for old-timers to tell by the fire. I mean, where, in this new century, could drugged wastrels get so close to both the Grateful Dead and Captain Beefheart in the same weekend?

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 135 (July 2009)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.