How prog was David Bowie?

From the Starman to Ziggy Stardust to the Thin White Duke, Bowie’s ever-changing persona saw him moving from folk to glam, pop to industrial, Krautrock to art rock with consummate skill and style

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

On Friday January 8 [2016], Prog’s editor wondered if this writer might be interested in writing an article about David Bowie and the progressive quality in his work, running all the way up to Blackstar, his latest album, released that same day – Bowie’s 69th birthday.

By Monday, January 11, the news had come in that it would, in fact, be his last ever album. And so this feature has become a conflation: part Outer Limits exploration of the prog-ness of his work, part requiem. A tribute to a truly progressive rocker, artist and man. It would be hard to argue for his musical virtuosity and super-proficiency on any of the instruments that he played, but if you’re talking dazzling sleight of mind when it came to realising radical and exciting ideas, and a willingness to create shock-art for the masses, there was no one more brilliant.

Bowie was the quintessence of prog: flamboyantly experimental, always pushing the boundaries, charting new territory and refusing to accept standard practice. He was to the 70s what The Beatles had been to the 60s, the avatar of ch-ch-ch-ch-change, albeit for more paranoid, confused, darker times.

If you regard prog as a series of codified rules, you might hesitate before allowing Bowie into its hallowed portals. But if you see the term in its most fluid sense – and Bowie was nothing if not fluid, a shape-shifting creature prone to transition just when you’d got used to his newest guise – you won’t flinch at his accession to the pantheon.

He certainly mixed in prog circles. Brian Eno was his partner in crime for arguably his most celebrated phase, being his foil at Hansa by the Wall and generally offering oblique strategies and clues as to where Bowie should go next. Rick Wakeman provided the keyboard flourishes for Space Oddity and Life On Mars; he was also famously invited to be a member of The Spiders From Mars on exactly the same day that he got the nod to join Yes. “It was like being asked to sign for Chelsea or for Manchester City,” he has said, and although he eventually plumped for Jon Anderson’s team, it wasn’t an easy decision to make.

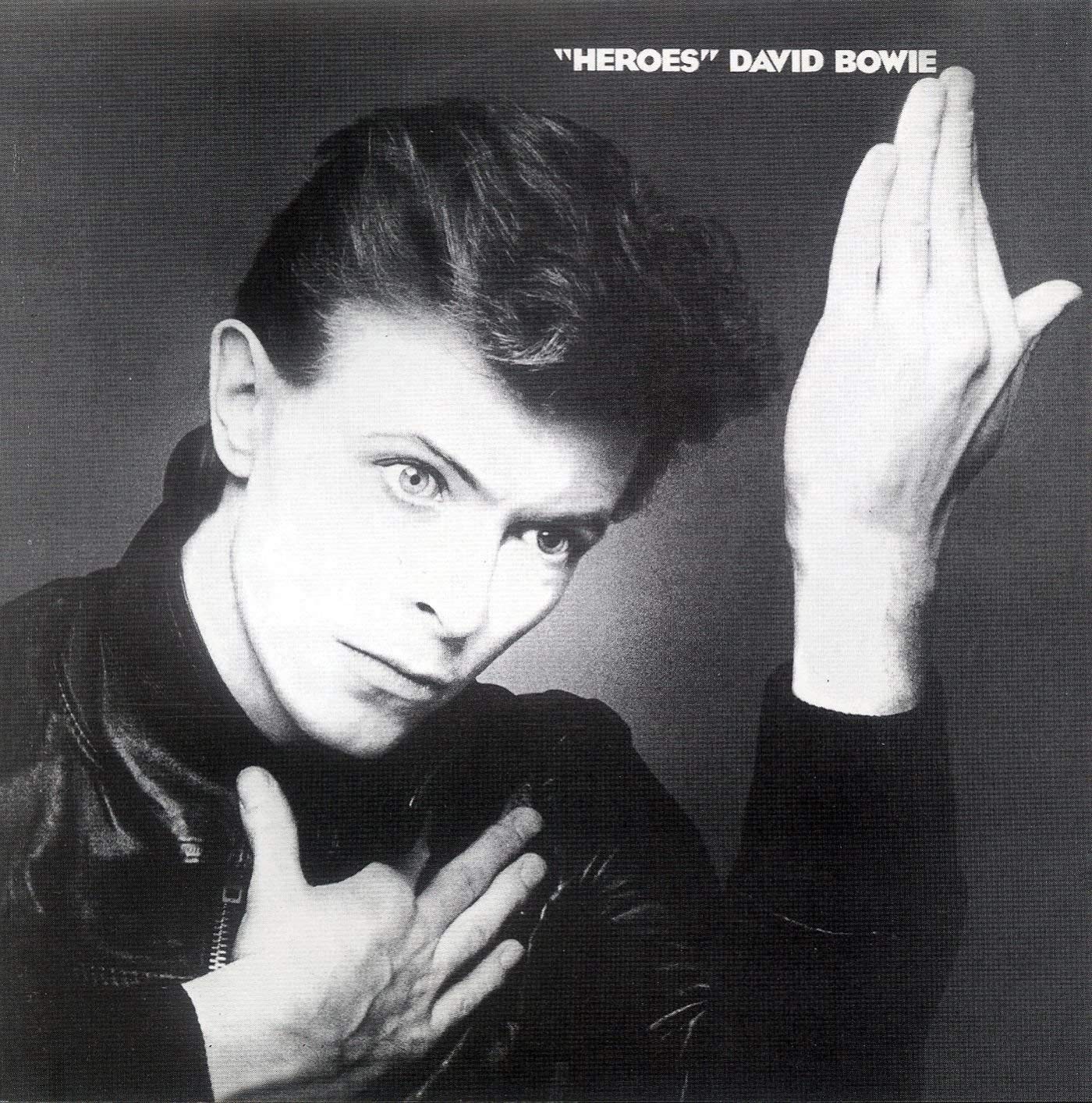

Robert Fripp was part of the illustrious squad Bowie took to Berlin, playing “hairy guitar” (Fripp’s phrase) on two key “Heroes” tracks: Beauty And The Beast and the immortal title track. Three years later, the Crimson King was back on Planet Bowie, supplying the harsh mechanical textures for Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps).

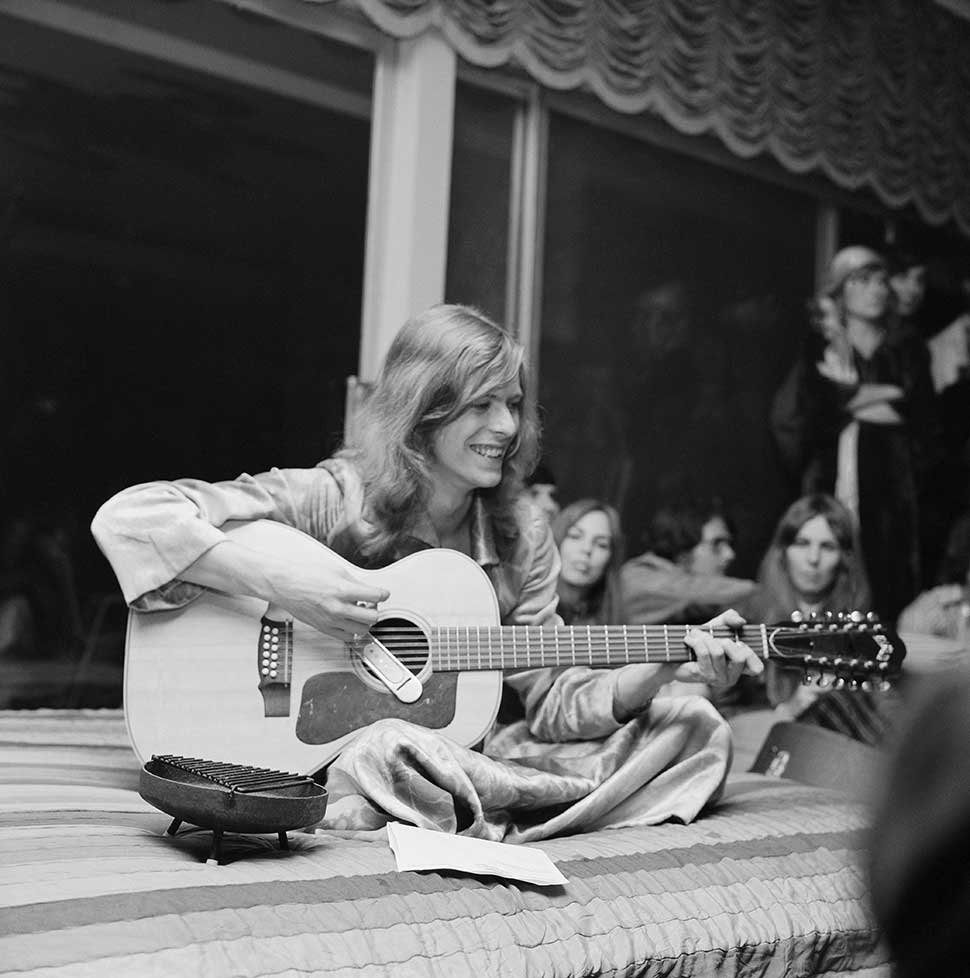

You might argue that a willingness to adapt and experiment are hallmarks of the genre, in which case, again, Bowie was supremely prog. There had already been several shifts and transformations before he even arrived in the spotlight. He was a blues rocker with the Manish Boys, a mod with the Buzz and a folkie with Feathers.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Bowie’s self-titled 1967 debut album was a curious mix of the theatrical and whimsical, music hall and psychedelia. Although it’s often dismissed as the work of a callow folkie, the also-eponymous 1969 follow‑up (issued as Man Of Words/Man Of Music in the US and reissued in 1972 as Space Oddity) featured several songs – notably the seven-minute Memory Of A Free Festival and nine-minute Cygnet Committee – which, in terms of riffing dynamics, extended instrumental workouts and sheer heaviness, had a lot in common with the burgeoning underground/progressive scene.

As for the opening track Space Oddity, it has been compared – tonally, texturally and in terms of its chord progression – to King Crimson’s Epitaph. Its use of mellotron was none more prog, as was its space/sci-fi imagery and sense of yearning for a faraway place. Bowie shared a fascination for the cosmic and futuristic with his prog peers, and a need, expressed by his lyrics and far-out sleeve art, to flee the banal and create a new reality. Just as The Moody Blues went In Search Of The Lost Chord and Hawkwind journeyed In Search Of Space, Bowie used Major Tom as the protagonist in his own moonage daydream.

The feeling expressed across Bowie’s music, lyrics and artwork is similar to that captured in the sounds and visuals of Yes, ELP et al. The individual ideas may have differed, from Ziggy Stardust’s leper messiah persona to the sci-fi armadillo tank of Tarkus and the giant hogweeds of Genesis’ Nursery Cryme, but the desire to use rock’n’roll as a portal to strange new worlds was largely the same.

Notwithstanding the often overlooked treasures to be found on its two predecessors, The Man Who Sold The World (1970) is widely regarded as the real start of the Bowie story. It’s certainly an early warning shot across the bow of anyone intent on putting Bowie in a neat box. It could be filed under progressive rock, although it could just as easily be categorised as blues rock, hard rock, folk rock, art rock, psych, even nascent heavy metal and an early sign of glam. But prog fans as much as anyone will thrill to the two-part, eight-minute album opener The Width Of A Circle, its lyrics less fantastical than sinister, with satanic and sexual overtones.

With its concise, adroitly conceived three- and four-minute paeans to Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol, Kooks and Queen Bitches, Hunky Dory (1971) may not have been prog on paper, but it will have enjoyed as much turntable space in sixth-form common rooms and student unions that year as Fragile, Tarkus, Nursery Cryme and Aqualung. It was also co-produced by Ken Scott, sometime engineer for The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Procol Harum and Mahavishnu Orchestra.

Indeed, despite its kaleidoscopic catchiness and exquisite accessibility, there was a gloominess to Bowie’s idiosyncratic vision (‘A million dead-end streets’) on Hunky Dory as he unveiled his mission statement (‘Turn and face the strange’) and announced his imminent takeover (‘Look out, you rock’n’rollers’). Life On Mars? was a baroque masterpiece in miniature and testament to Bowie’s genius knack for bringing esoterica into the mainstream. The series of unsettling images may have seemed unpalatable, but the context – Wakeman’s piano, Mick Ronson’s ravishing string arrangement – was so appealing that before long, kids in playgrounds across Britain were singing about ‘The mice in their million hordes/From Ibiza to the Norfolk Broads’ and rhyming ‘America’s tortured brow’ with ‘Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow’.

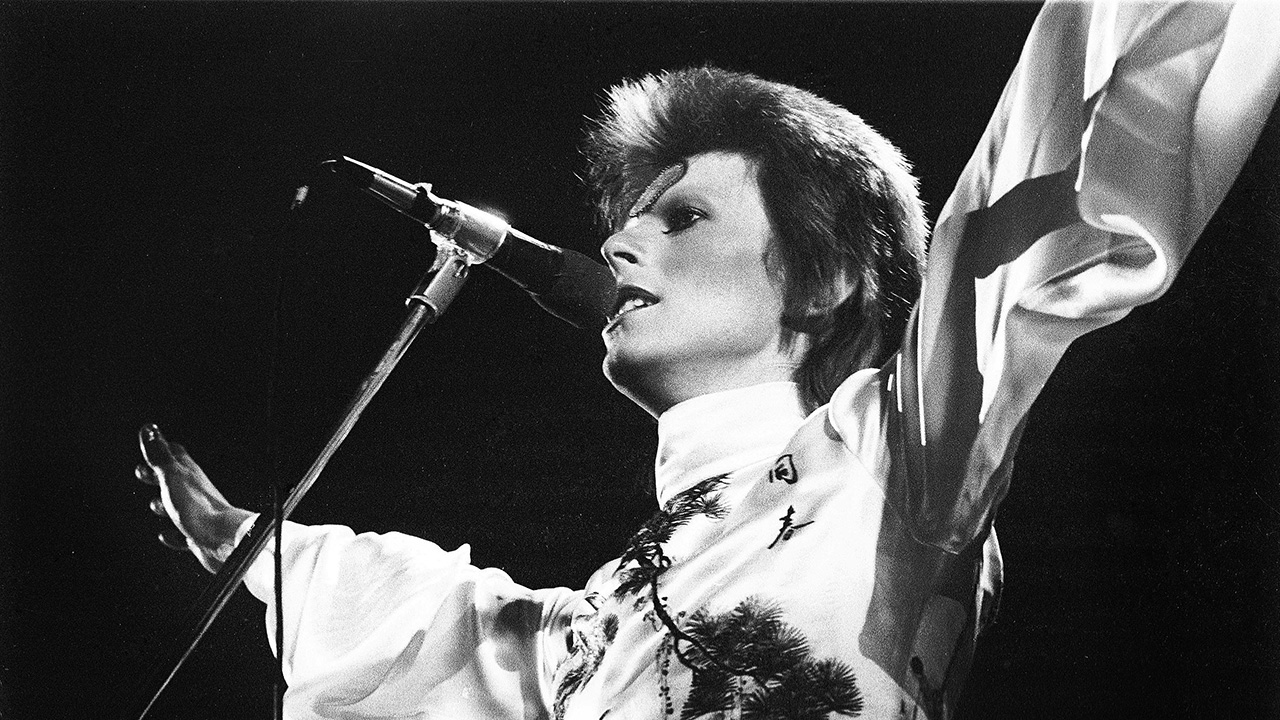

Close To The Edge, Foxtrot and Thick As A Brick weren’t the only thematically unified albums with a coherent vision from 1972. There was also a modest little collection called The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. Here, Bowie’s audacious tendencies – musical, lyrical, sexual – achieved full flight. If you really want a measure of The Solid Time Of Change, then watch Bowie and Mick Ronson blow accepted notions of rock masculinity clean out of the water on that edition of Top Of The Pops, where they unleash Starman on an unsuspecting populace – at teatime, no less.

Ziggy Stardust functioned as escapist fantasy and grim parable about the realities of fame, and made the orange-haired bisexual alien a household name, even though – or rather, because – we didn’t know where Bowie ended and Ziggy began.

Aladdin Sane (1973) further fractured the fault line between fiction and reality, being the first album Bowie made as a bona fide star. The title track alone, with Mike Garson’s freaky avant-garde piano heightening the sense of disturbance, managed to conflate reflections on insanity and intimations of the apocalypse.

Bowie was the harbinger of doom, in the guise of a human-canine. Diamond Dogs (1974) was another outlandish concept that sustained the mood of imminent cataclysm, with the epic song suite comprising Future Legend, Diamond Dogs, Sweet Thing, Candidate, Sweet Thing (Reprise) and Rebel Rebel on side one surely being palatable to prog heads – comparisons have been drawn between Bowie’s nightmarish eighth album, based on George Orwell’s 1984, and Rush’s equally dystopian 2112.

One of the tracks on Diamond Dogs, 1984, was an orchestral funk number that pointed towards Bowie’s next move – the so-called “plastic soul” of Young Americans (1975). By this point, the alien androgyne’s experimentation included a foray into cinema – with The Man Who Fell To Earth, forever capturing his mythic extraterrestrial aura – and a descent into the narcotic underworld that would have felled a weaker character. There was a concomitant obsession with witchcraft and black magic, while he became mired in a sort of living hell in LA.

Naturally, being Bowie, he made his adventurism work to his advantage, and by Station To Station (1976) he was reborn as The Thin White Duke, with one eye on the Philly soul past and another on the electronic dance future, with some Teutonic present-tension from the German music (aka Krautrock) that he’d been listening to.

With the help of Eno, Fripp and producer Tony Visconti, he then made a critical move to Berlin, accompanied by a shift in attitude and aesthetic value. Low and “Heroes” (both 1977) were the results – albums of modern pop on one side and starkly beautiful instrumentals on the other. It may have been the height of punk, but Bowie was every bit as relevant as Johnny Rotten and his cohorts. Or as the famous advert of the time had it: “There’s old wave, there’s new wave, and there’s David Bowie.” The 80s started here.

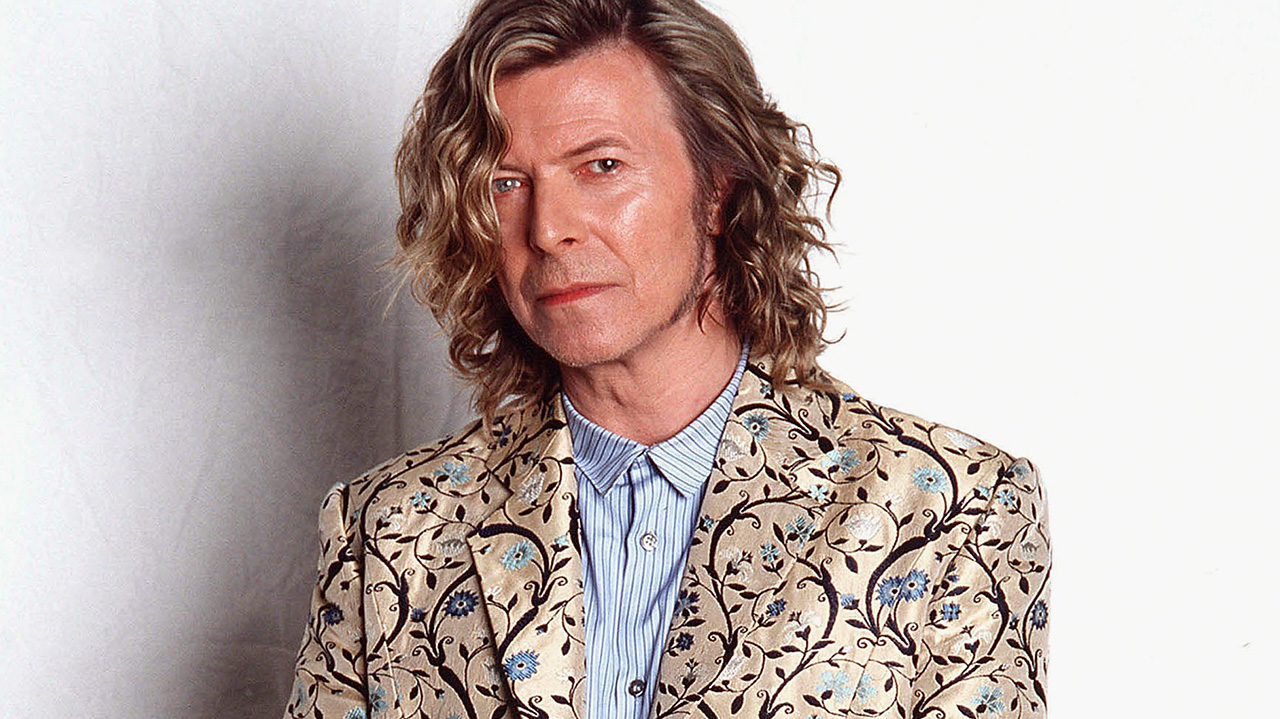

Arguments rage as to which Bowie album was his last great addition to his peerless canon. Some say it was Lodger (1979), others venture that it was Scary Monsters (1980), while many cite Let’s Dance (1983) – his commercial high-water mark, the one that turned him into a global superstar – as the one. Outside, his 1995 album that saw him collaborate once more with Eno, is now regarded as a late example of Bowie’s unstinting progressive tendencies.

And then, of course, there’s The Next Day (2013) and Blackstar, the latter released, uncannily, two days before his death. Uncanny because it featured so many poignant, even chilling, portents of his demise (‘Look up here,’ goes the opening line to the single Lazarus, ‘I’m in heaven’), as though he knew all along that it was coming – that it was the final act of subversive strategy from a man who had seemingly plotted his every creative move for five decades.

“He always did what he wanted to do,” declared Visconti, producer of Blackstar, on the day Bowie died. “And he wanted to do it his way and he wanted to do it the best way. His death was no different from his life – a work of Art.”

Total commitment to artistry, to provocation and to change, in life as well as death. How prog is that?

This article first appeared in Prog Magazine issue 63.

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.