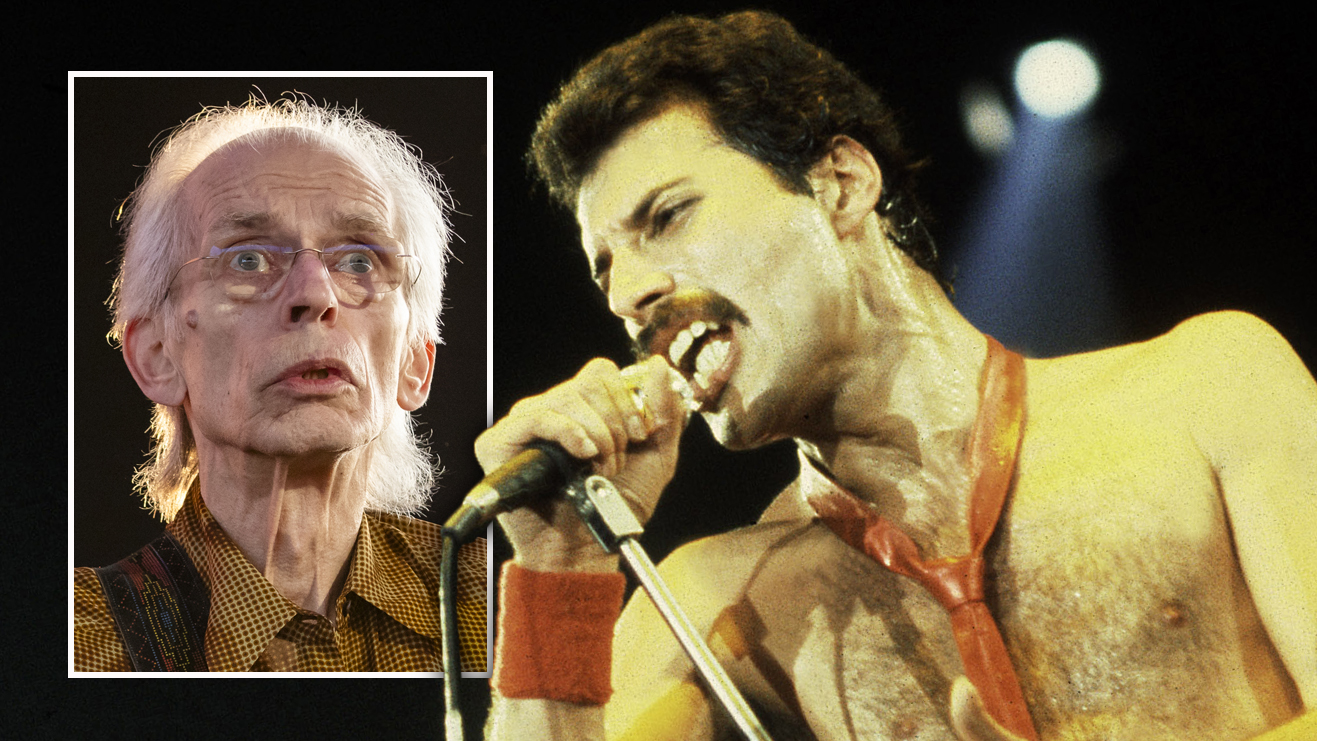

“If you want to play that kind of music, play it on your solo album. I’m not interested”: In 1971 Greg Lake enraged Keith Emerson, who immediately quit ELP. The result was their acclaimed album Tarkus

Carl Palmer recalls a crisis meeting, arguments over time signatures, and playing the whole album top to bottom in the studio – only to discover their engineer had taken a break

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 1971 Emerson, Lake & Palmer pushed the boundaries of popular music with the release of Tarkus. Although now regarded as a classic, their second album was all but slated by the critics at the time. As the conceptual opus celebrated its half-century in 2021, Prog explored its creation and the rise of it creators – one of the movement’s greatest and most unique bands.

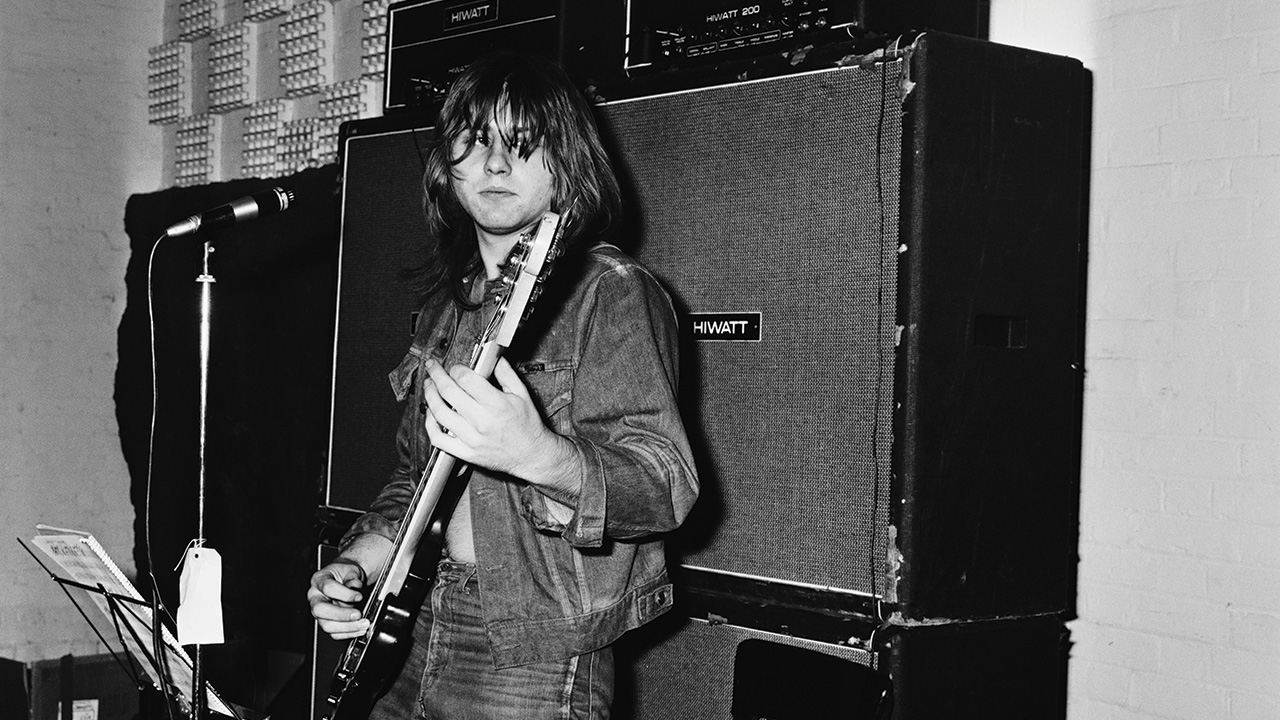

Greg Lake could never be described as someone who was slow in coming forward, especially when he felt you needed the benefit of his opinion. “If you want to play that kind of music, you should play it on your solo album,” is what he told Keith Emerson, after the keyboardist played him the opening motifs of a new piece intended for their second album. Lake added: “I’m not interested in that sort of thing.”

Emerson hadn’t expected such a negative reaction after inviting his bandmate to his home for a listen. Already taken aback by such brusque dismissal of his work, he was astonished further still as the bassist and vocalist got up left.

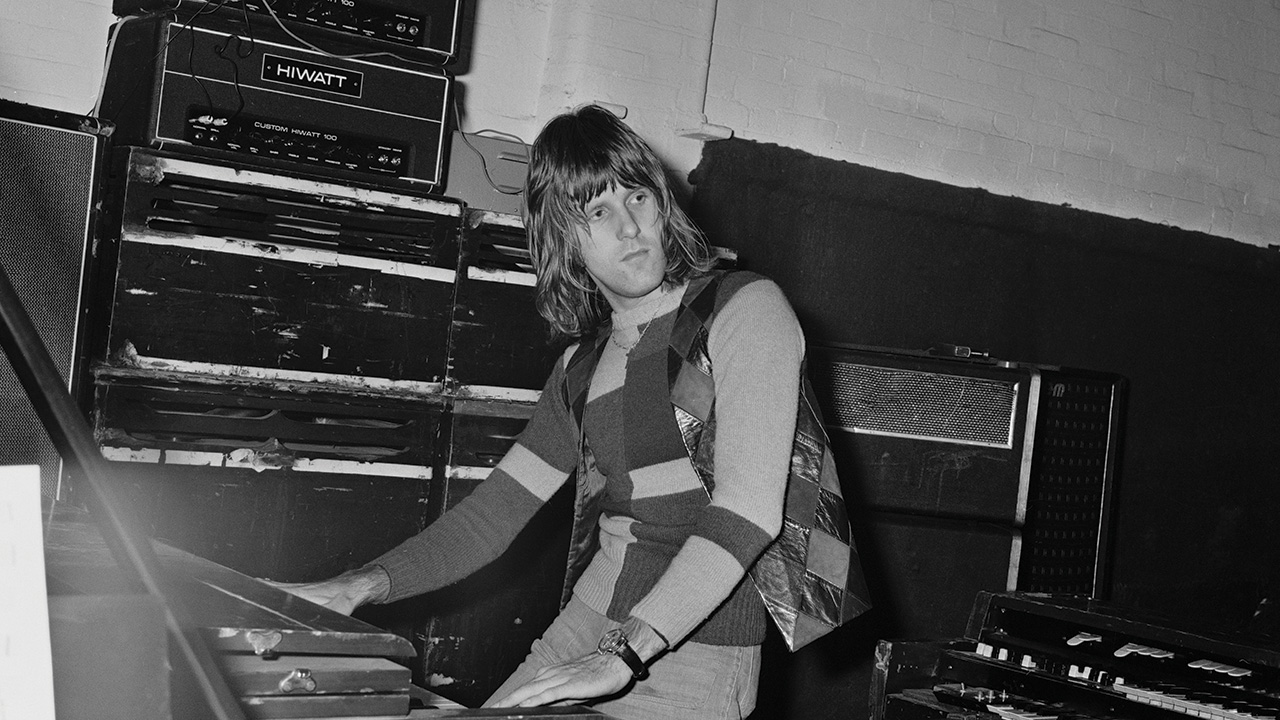

His astonishment very quickly turned to anger. He’d been inspired to write the piece after Carl Palmer had come up with a knotty drum pattern. Galloping across a 10/8 metre and drawing upon influences as diverse as Frank Zappa and his beloved Argentinian composer, Alberto Ginastera, it felt and sounded like the future to him.

To have it roundly rejected in such an offhand manner deeply offended him. What had been intended to be a celebratory unveiling was mired with discord and uncertainty. Picking up the phone, Emerson got straight onto John Gaydon, the ‘G’ of EG Management, telling him in no uncertain terms that Emerson, Lake & Palmer were finished.

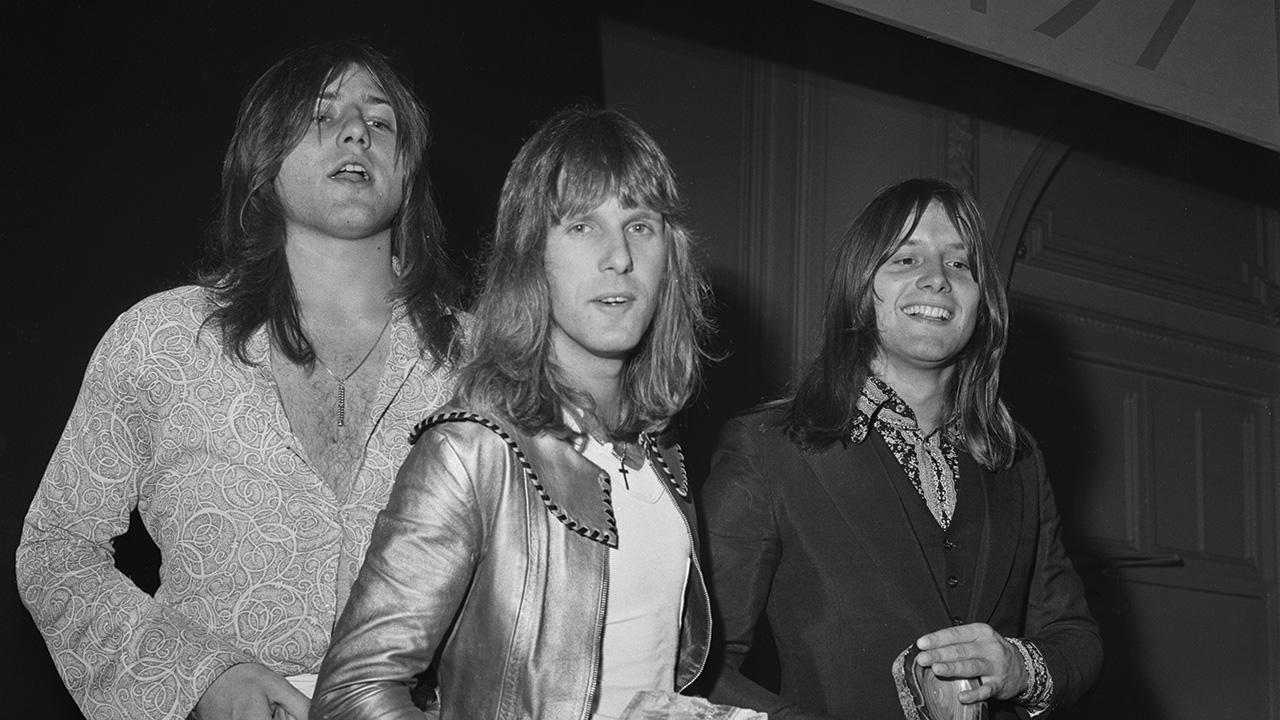

In 1970, following a small warm-up gig in Plymouth, ELP had arrived on the world stage amid the roar and flash of cannons at the Isle Of Wight Festival in August 1970 before 600,000 people. Now, just a few months later, with their self-titled debut album riding high on both sides of the Atlantic, the group were £30,000 in debt and needed another successful record to stand any chance of becoming a profitable concern.

At a meeting convened at EG’s offices the next day, the differences between the three musicians were aired without any pulled punches. In The Nice, Emerson had been used to holding a dominant position; while bassist Lee Jackson and drummer Brian Davison would express their views, the group’s creative direction of travel, governed by Emerson, was never questioned.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The situation he now found himself in shouldn’t really have been a surprise. Blessed with a sometimes overbearing self-confidence that belied his 23 years, Lake’s opinions of his own abilities and strengths were bolstered by his time in King Crimson and their meteoric success. His lack of diplomacy was carried over from Crimson’s rehearsal room – a tough and sometimes brutal environment in which he’d been more than capable of holding his own.

While he’d spent some time at Wessex Studios’ mixing console as Robert Fripp’s band recorded 1969 debut In The Court Of The Crimson King, Lake was a relative novice compared to Emerson’s long-established history of making records. Little wonder, then, that tensions and eyebrows were raised when Lake had unilaterally declared he alone would take the producer’s credit on ELP’s first album.

Lake’s objection to Emerson’s new piece wasn’t that he didn’t like it, but that it wasn’t what he regarded as commercial. It wasn’t the gothic ruminations of Emerson’s The Three Fates that had secured ELP round-the-clock airplay on American radio, but the Lake-penned Lucky Man – which, notwithstanding Emerson’s ebullient Moog solo at the end, was essentially a conventional ballad. What Lake wanted from Emerson was material he could collaborate with and build upon.

At the crisis meeting, Carl Palmer – who hadn’t been consulted by either faction on the issue at hand – had asked, “Don’t I get a say?” Things were very much resting on a knife-edge. Was Emerson being dictatorial? Was Lake being a prima donna? Between their respective egos, the truth was probably somewhere in between.

Eventually, both parties were talked down off the ledge by Gaydon. With studio time already booked, Emerson and Lake were persuaded to give things another go, and an uneasy truce was agreed. That all this had to be hashed out and mediated before a single solitary note of Tarkus was committed to tape illuminates the inner world of the band.

“ELP never argued over money, never argued over women, never argued over any affairs like that,” Palmer laughs. “The only thing we’d argue over was music. We could argue over four bars for about four years! Yes, there were some real tensions within ELP – but that’s good

“You always get someone who wants to play a little bit safe and you always get someone who wants to turn it up. Because I wasn’t one of the main writers, my position was as a referee between them. I wouldn’t side with anyone – I’d say exactly what I thought about the music. They’d take it from me if I said something was not that good.

“No one else would ever go up to them; no one from the record company or the management. It wouldn’t happen that way. There was an inner trust which ran very deep. They knew I wasn’t going to walk in with a carrier bag of songs and say, ‘This is what we should be playing.’ I was about trying to get the best out of everyone and they understood that. Greg trusted me implicitly on that score.”

We wanted Greg to write us three-minute songs that got us on radio, and Keith to steer the boat toward the prog rock we liked to play

Carl Palmer

Admitting that “there were moments between us, of course – there are always going to be moments,” the drummer continues: “But I’ll tell you what, not one of us ever sat on the fence. We each had a role, and although I wasn’t a writer, my position was about the organisation of the band, which I got involved with in a big way. I’d write everything down and make sure everybody was literally on the same page. We wanted Greg to write us the three-minute songs that got us on the radio, and we wanted Keith to steer the boat toward the prog rock we liked to play.”

For a work whose central narrative addresses conflict, their ability to compromise makes Tarkus greater than the sum of its parts. It’s undoubtedly true that Emerson established his momentum as a mature composer with the Tarkus suite, and created a piece that has since gone on to be one of his enduring legacies. It’s equally true that it wouldn’t be the same beast without Lake’s decisive contributions.

Though reticent to begin with, when the band stepping into Advision Studios during the chilly winter of January 1971, in the end, Lake threw himself into the work, delivering remarkable bravura performances of his own. With the hypocrisy of politics and religion as his lyrical targets, Stones Of Years provides a moment of reflective respite, while Mass introduces a collection of characters and archetypes that sound like they could have been conjured up by Lake’s ex-Crimson bandmate Peter Sinfield.

Lake’s track Battlefield – brilliantly set up by Manticore’s frenzied climax – brings in a sweeping, sombre majesty. For all Emerson’s association with the Moog synthesiser, the track and much of the album is largely a vehicle for traditional keyboards along with the Hammond organ’s endless versatility. The synth is used sparingly throughout as a painterly highlight rather than principal colouring. Of course, it’s that spareness that ensures its appearances are both dramatic and extraordinarily memorable.

We played it from top to bottom. It was absolutely great. We said, ‘You did record it, didn’t you?’ He said, ‘I’ve just come back from a break. It’s been a long day’

Carl Palmer

However, on Battlefield it’s Lake’s soulful guitar soloing – which conjures Peter Green’s thoughtful style in early Fleetwood Mac – that provides not emotional release, and in some respects, the climax of the piece overall. It’s as though all the preceding movements were building to that point. As guitar lines swoop like carrion birds above the carnage so graphically described in the lyrics, Lake’s vocal beautifully articulates both the sense of loss and judgemental anger invoked within the track.

“Once Greg got the guitar sound he wanted, they were almost always like a first take; there was never a problem there,” says Palmer. “The vocals, on the other hand, always took longer.”

Throughout the Tarkus suite, Palmer’s work underpins the music through his energetic and highly orchestral approach, providing a constant flow of percussive annotations that accent and dramatise key moments while giving each section a seamless continuity. The time that he and Emerson spent running through the piece pays off with a wholly integrated drum score that’s musically robust.

The 21-minute opus remains a personal favourite of his. “I think the initial theme, when it starts with the voices producing the chord into the 10/8 or 5/8 time signature – that is, the main Tarkus theme – is absolutely stunning. Even today the hair stands up on the back of my neck. The songs are all great and really cool, but the actual theme itself, as it starts the piece and where it ends, really is marvellous.”

What makes all this even more astonishing is that it was all done in five days. Recorded in a series of discrete sections, Palmer says the final running order required 17 separate edit points. “We marked out the sections where you could actually cut without a chord or a cymbal hanging over, to make sure it was a clean splice. I remember that day because it was gruelling; but at the end of it all Keith said, ‘Why don’t we play it all the way through just for the hell of it?’ We went back into the main studio and played it from top to bottom. It was absolutely great.”

Afterwards, they asked engineer Eddy Offord to play it back. “He had no idea what we were talking about. We said, ‘We just played the whole thing. You did record it, didn’t you?’ He said, ‘I wasn’t here. I’ve just come back from a break. It’s been a long day.’”

I write music with a view that it will be valid in 10 or more years’ time. I can’t be that presumptuous to say whether it will be

Keith Emerson

Palmer is unstinting in his praise for Offord – immortalised on album closer Are You Ready, Eddy? a title which possibly refers to that moment. “He was the guy that brought all of the sounds together for ELP,” the drummer says. “He wasn’t just an engineer – he was a producer, an exceptional guy who we all really looked up to. He really understood the music and knew how to direct the musicians to get the best out of them.”

Still a side short of a completed album, the band were booked into Advision Studios for another seven days, despite having little in the way of properly developed ideas. At another stage in their career, ELP would be able to dictate how much time was required to nail down new material. In February 1971, however, no such consideration was possible as they sought to feed the voracious demands of recording and touring. It’s that commercial pressure that arguably led to the second side of the album’s lack of structural integrity and cohesiveness, which they’d achieved so well with the title track.

If Tarkus feels somewhat uneven, it stems from the bookending of side two with the Vaudevillian quirkiness of Jeremy Bender and Are You Ready, Eddy? – more filler than anything else, neither piece shows the band at their best. However, the other tracks stand up well despite the haste of their creation; Bitches Crystal, which stylistically harkens back to The Nice, became a live favourite over time.

Partially inspired by British bandleader Johnny Dankworth’s African Waltz and the Buddy Rich Big Band’s 1967 Beatles cover, Norwegian Wood, Palmer suggested to Emerson that a jazz waltz feel would be a good vehicle for melodic writing. Bitches Crystal was Emerson’s response; featuring some of Lake’s most acerbic vocals, Palmer argues it’s been overlooked for years – and with it, Lake’s vocals. “It was always a standout piece for me. It was slightly different from the other things we were doing. Greg’s vocals are very strong on this album and I think his voice even at its most extreme is the strongest it ever was. He sang really well.”

That voice is especially striking wreathed in the cathedral-like ambience of The Only Way (Hymn). Questioning man’s reliance on God, it soars above the glowering filigree of Emerson’s pipe organ, recorded at St Mark’s Church in North London. As it ripples with quotes from Bach, the chest-rattling bass notes possess a forbidding, sterner counterpoint to Lake’s plaintive register. Transitioning into a jazz trio in the manner made popular by Jacques Loussier’s Bach interpretations, Emerson’s freewheeling playing shines with effortless grace.

Tarkus was a blueprint for us, really. It was the way to take progressive music

Carl Palmer

That freedom of movement stands in marked contrast to the dogged minimalist blocks of Infinite Space (Conclusion). “We were sort of humming and singing around the piano, just the two of us,” recalls Palmer. “It was something he’d played but hadn’t noticed, so I pointed it out to him, and then we got that sort of funny kind of riff going on. It was one of those moments that didn’t happen many times. Generally, Keith was a loner as far as writing music goes. Once he’d got some ideas, he’d see if we could embellish them; but in this particular situation it was from the get-go.”

There’s an almost brutal, pounding force at work in the stubborn rhythm and the insistent piano motif. With its clashing tonalities, there’s an experimental aspect that challenges and intrigues, suggesting a possible direction – that the band sadly would never explore in any depth.

A prime slice of ELP in their rocking pomp, there’s a case to be made that had A Time And A Place been repositioned as the album’s finale, its ascending Moog line would have acted as a timbral callback to the previous side and tied the album together. As it is, that job fell to the cover artwork.

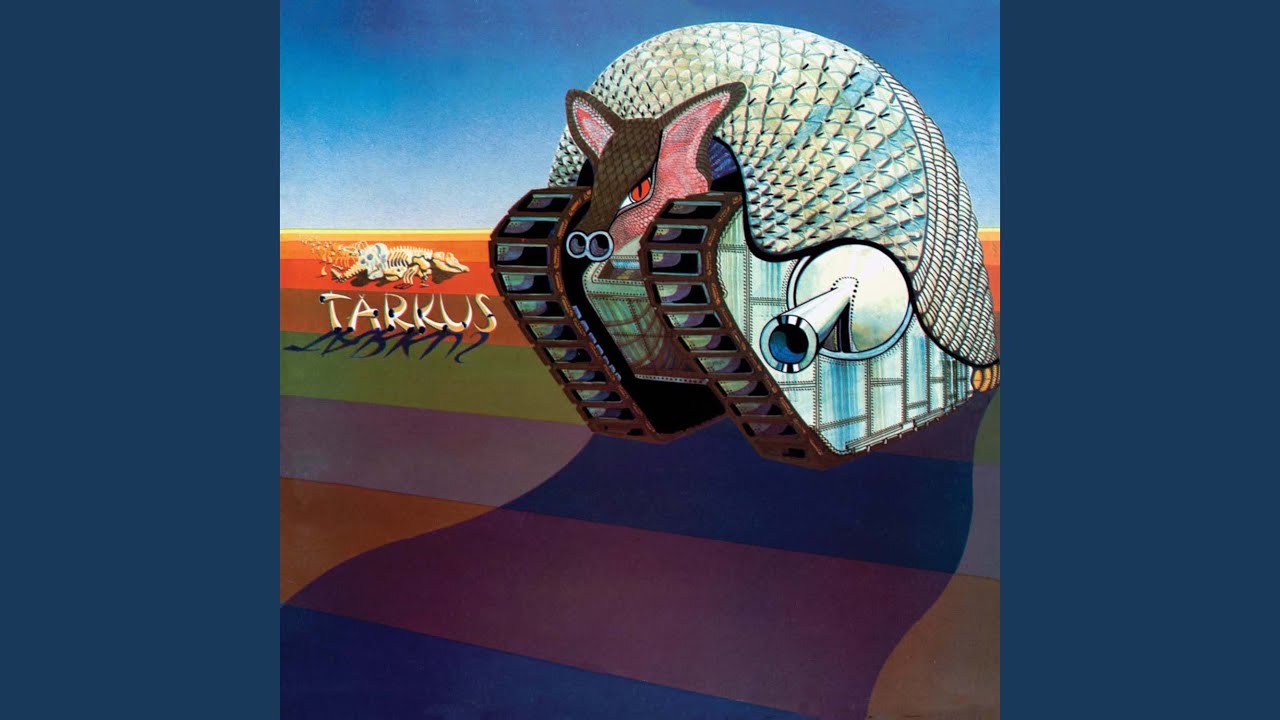

“We knew it would catch people’s attention,” says Palmer of artist William Neal’s painting. The surrealist sci-fi-themed image of a murderous cyborg armadillo also gave the band a strange kind of mascot, a visual hook, and an outsized stage prop that has proved as enduringly popular as the music itself.

In 1971 Emerson said, “I write my music with a view in mind that it will be valid in 10 or more years’ time,” although he added: “I can’t be that presumptuous to say whether it will be valid or not.” He needn’t have worried, though. Having passed 50 years, Tarkus most definitely stands the test of time. Had wiser heads not prevailed that day in EG Management’s offices, ELP would have been a glorious but doomed one-act band, a footnote in progressive rock’s story rather than a foundational act.

Tarkus began as a vehicle for Emerson’s musical ambitions and became an audacious triumph. An album that could so easily have been a breaking point ended up consolidating their future, taking them to the top of the UK charts on its release in June 1971, and into the Top 10 of the US charts.

Palmer has nothing but affection for the record and the period it represents for him. “In those days ELP were always in the studio collectively. Whether or not we were all in the control room at the same time, we were always there to make decisions on the work that had been done during that day.

“I think Tarkus was a blueprint for us, really. It was the way to take progressive music; and although it initially had a lot going against it and there was an awful lot of friction, that’s a good thing. We came through it and Tarkus ended up being one of our biggest pieces.”

Sid's feature articles and reviews have appeared in numerous publications including Prog, Classic Rock, Record Collector, Q, Mojo and Uncut. A full-time freelance writer with hundreds of sleevenotes and essays for both indie and major record labels to his credit, his book, In The Court Of King Crimson, an acclaimed biography of King Crimson, was substantially revised and expanded in 2019 to coincide with the band’s 50th Anniversary. Alongside appearances on radio and TV, he has lectured on jazz and progressive music in the UK and Europe.

A resident of Whitley Bay in north-east England, he spends far too much time posting photographs of LPs he's listening to on Twitter and Facebook.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Emerson, Lake & Palmer - Infinite Space (Conclusion) [Official Audio] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/URbaciLz1l0/maxresdefault.jpg)