“The edges were bound to fray – we were bound to take from each other. David Gilmour openly accused Roger Waters of copying me”: The influential folk singer-songwriter who never quite gained stardom, but gained massive respect instead

Acclaimed by Pink Floyd, Kate Bush, Led Zeppelin and Peter Gabriel, he recalls feeling insulted by the way his best-known album was treated, his short stint in a US prison, and his decision to stop writing long notes to fans on their record sleeves

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

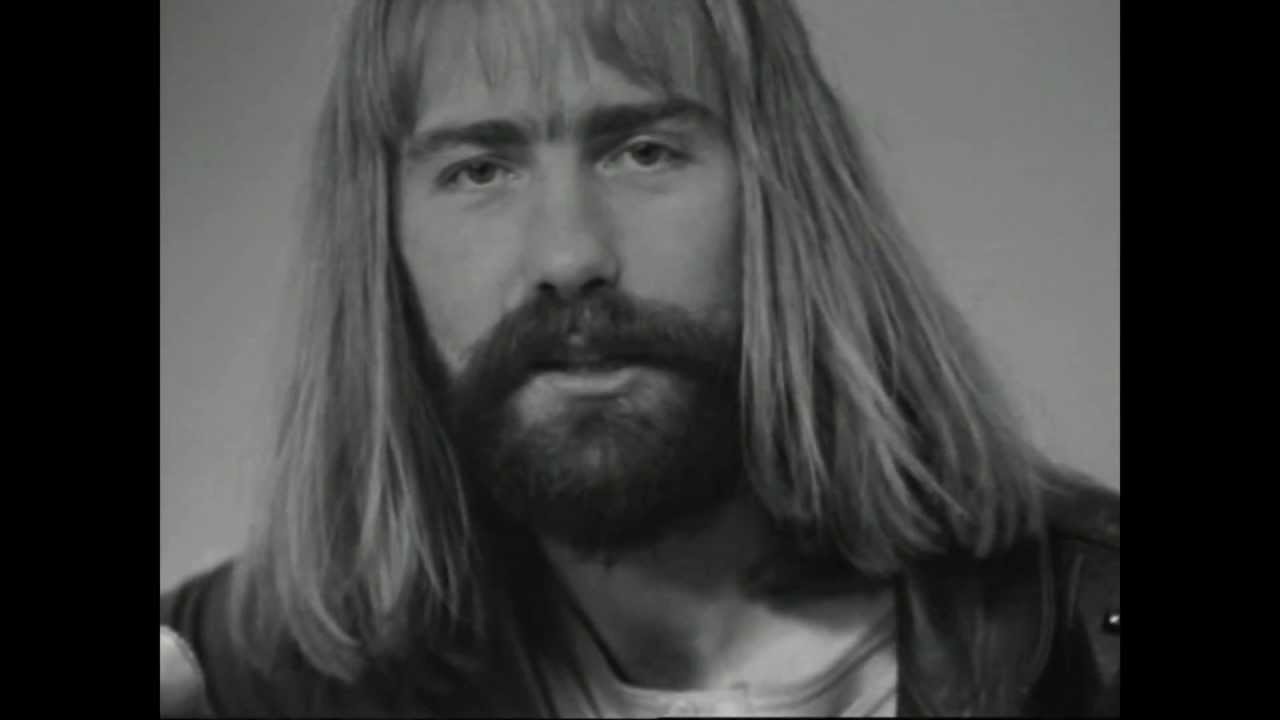

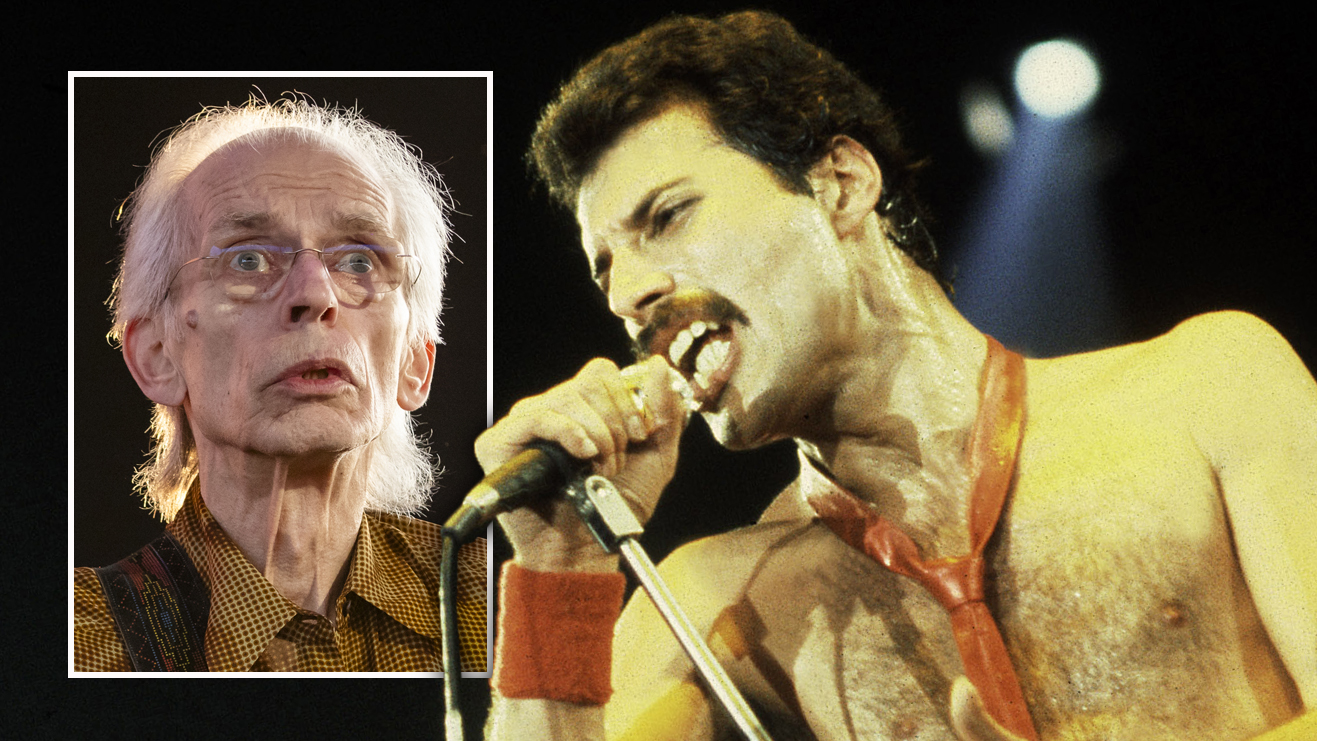

Since the mid-60s progressive folk singer-songwriter Roy Harper has enjoyed a successful solo career and also collaborated with everyone from Pink Floyd and Peter Gabriel to Kate Bush and Led Zeppelin – but never quite reached the commercial heights of his peers. He looks back over highlights from his career so far and teases a new album.

Not for the first time, Roy Harper is considering his art. “In order to remain current, songs have to pertain to what’s happening in a modern sense,” he declares. “I always aim to write with a sort of timelessness; that’s the number one consideration.”

It’s an MO that’s served him pretty well down the years. His greatest long-form songs – be it I Hate The White Man, The Same Old Rock, One Of Those Days In England or When An Old Cricketer Leaves The Crease – transcend the era in which they were written.

Harper has largely been a social commentator, training his lens on issues ranging from institutional dogma to ecological collapse and various points between. He’s the rebel poet who started out in the folk clubs of 60s Soho – centred around the fabled Les Cousins – and bloomed into one of Britain’s most vital talents.

“People have lumped me in with prog for a long time now,” he says. “But when does folk become prog? And when does Roy become folk? There are various questions to be asked there.”

At 84, Harper is still tricky to categorise. Jazz, blues, rock and classical music have formed the constituent parts of his output, which hit a creative peak during a 70s run that included HQ, Bullinamingvase and the ravishing Stormcock. Commercial success, however, never quite materialised – instead, he’s had to make do with something more akin to cult hero status.

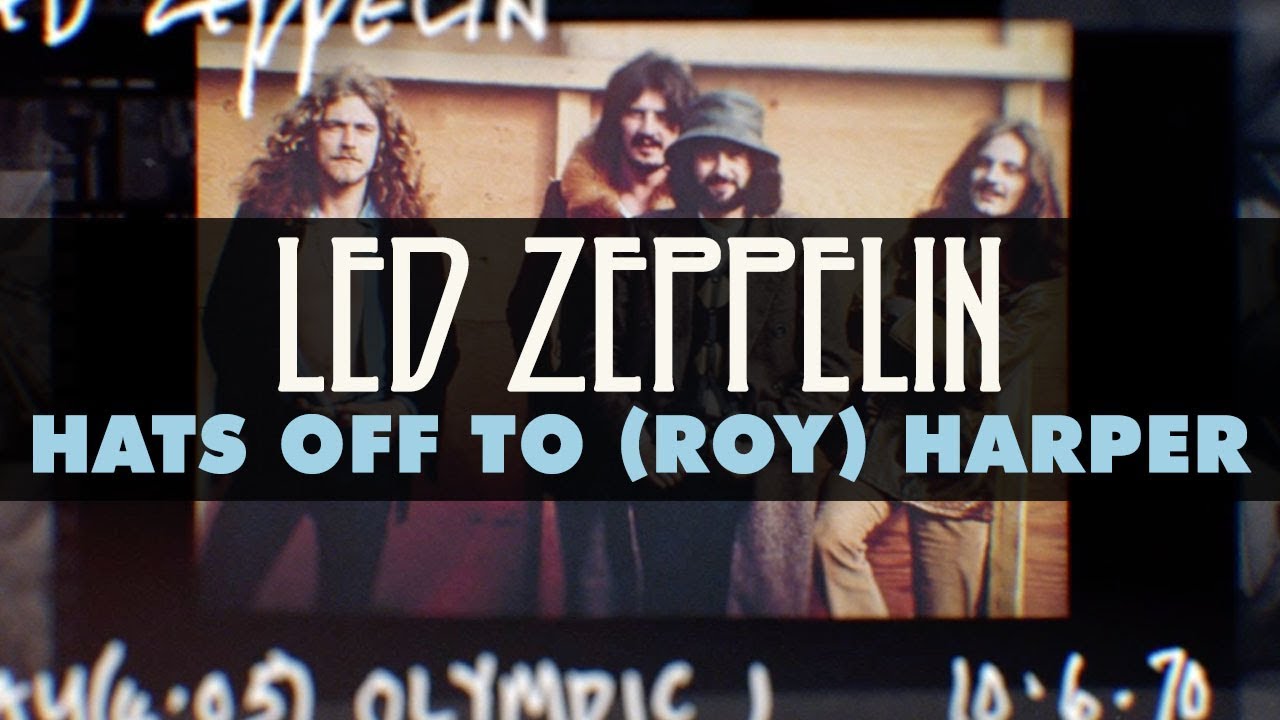

His friends Led Zeppelin paid tribute with 1970’s Hats Off To (Roy) Harper. Pink Floyd invited him to sing on their Wish You Were Here album. Other collaborators have included Paul McCartney, Ian Anderson, Bill Bruford and Kate Bush, who also covered the sublime Another Day with Peter Gabriel.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It’s now 70 years since Harper first picked up a guitar. Initially inspired by the Beat Generation – “I was probably the leading beatnik in Lytham St Annes, French beret and all,” he says with a laugh – he got serious by the time he was 18, starting a skiffle band that “kind of veered into electric.”

This might be a good time to mention that the group’s four-song acetate was stolen from a drawer in Harper’s house in 1992. He’d really like to know where it is. “It’s probably worth quite a lot of cash, because it’s a record of the first thing I ever did,” he explains. “I don’t need the actual thing back, I’d just like a copy of the music.”

This is just one of a number of things on Harper’s mind as he talks to Prog from the house that he shares with wife Tracy on the south-west coast of Ireland. There are also the swallows that keep flying in through the windows and attempting to nest in the vestibule. And the memoir that he began some time ago. Progress is tough: “I’ve started it, but I’m still only at the age of about 13 or 14.”

So, was The Final Tour: Part Two really your last tour?

I’m prepared to run the gauntlet. A year ago, I was kind of retired, but I began to realise that it was false. I’d been in that position for a few years, and I’d been messing around writing. I just thought, “You’re still playing, Roy, and you’re singing. And you still haven’t made the record that you were going to make four years ago. What’s the score, mate?”

So, I thought about doing Glastonbury again. I got hold of my promoter, who got hold of an agent, and suddenly I was there. It’s crazy, really: I kind of bump-started myself. The older you get, the more impulsive you become.

Your son Nick was with you on those September dates, which coincided with the release of his live album, 58 Fordwych Road, named after your old home in London. Bearing in mind it’s now 60 years since you first appeared at Les Cousins, there seems to be a cyclical feel to this whole venture.

Yeah. I think I first got to do floor spots at Cousins in July ’65, and then it quickly developed into something else. I was building myself up. By August I’d done a couple of gigs there and it was obvious that I was going to become a regular. That was around the first time that I appeared in Melody Maker.

Do you grow a little wistful today when you think about London – and Soho in particular – during the mid-60s?

Soho was a melting pot. Some of the best people of the age started their lives there. I was reborn there

Oh, absolutely. I miss England. And I kind of know, sadly, that I’m not going to live there again. But I want to go home at some stage. I could up sticks and go and live in a glorified bedsit or whatever, but there’s so many responsibilities here. It’s crazy to think about moving. And I do have some very good friends in Ireland, so I’m not bereft of really good company here.

What was it about Soho that was so crucial to who you became?

On Greek Street you had The Establishment club, with Dudley Moore and Peter Cook and all the young Pythons. And then almost opposite that was Cousins, which was folk central and more, because you also had people like Champion Jack Dupree playing there. Just off Charing Cross Road was Bunjies, where Al Stewart eventually set up home.

Then you had The Marquee on Wardour Street and UFO at the Blarney Club on Tottenham Court Road. There was so much going on: rock’n’roll, folk, jazz, comedy, all within about 600 yards of each other. It was a melting pot. Some of the best people of the age started their lives there. I was reborn there. And it was where I found everybody else who was going to be part of my life.

You got to know Pink Floyd and Marc Bolan, alongside leading folk musicians like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and Davy Graham. Did it feel like one big community, rather than a competitive environment?

For me it did, because I travelled into different arenas – I had bits and pieces of everything. I was kind of outlawed by the trade people, yet I knew the guys in Cousins, like The Young Tradition, and to some extent The Watersons. And Anne Briggs, who was Bert’s girlfriend at the time, was a friend.

So I enjoyed all of it and started thinking about what I could take from it and put into it. I’m very catholic with my tastes, in the original meaning of the word.

What would you say was the first song of yours that you were really satisfied with?

My dad listened to ice skating on the radio – seriously! They played all kinds of classical music and I gravitated to the emotion

I think Forever was the awakening, in August ’65. That was the first song I wrote in the vernacular that I’d started listening to. I was writing poetry at night, and suddenly I got into Cousins and I was singing things like St James Infirmary. I wrote Forever for Nick’s mother. It was a direct result of Nick’s birth; so all of that’s bound up together.

You appeared alongside Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, Tyrannosaurus Rex and others at the first Hyde Park Festival in 1968. Did it feel like a moment?

Absolutely. And the fact that Hyde Park is common ground added to the feeling. It was like a really joyful congregation of people who were of the same mind or character that was being formed right at that moment. It was different after that; it quite quickly became commercial.

But that first one was a gathering of young minds doing their thing, thinking about the world and exchanging ideas, like selling Oz magazine or whatever. There was a feeling that it was going to become greater, because it was bursting out of its seams. And to be there on that day was kind of like a “Hallelujah!” moment.

At Hyde Park you talked about doing a rock opera with Pink Floyd. What became of that?

I was very friendly with Roger at the time. He lived down in Chelsea and I went round there a couple of times. We got even closer at Abbey Road, but then apart as well. So there’s a rugged history there. The rock opera was just an idea, and I think someone mentioned it in Sounds. But we were talking about everything else as well. I mean, what do you talk about when you’re that age?

You recorded your first three albums – Sophisticated Beggar, Come Out Fighting Ghengis Smith and Folkjokeopus – in accelerated bursts of time for different labels. What was the big difference once you’d signed to Harvest for 1970’s Flat Baroque And Berserk?

That’s when I was thrown into the furnace that is Abbey Road. I got to find out about all the toys that were available to use. Ken Townsend was the guy who ran it, and there was a room full of guys who could fix things for you. I was like a fish who was already swimming in different ponds, but that was my introduction to the ocean. Once I was ensconced in Abbey Road, I didn’t waste any time. I just thought, “OK, it’s coming now!”

Stormcock was a new direction for people to look at. If the label had had faith in it, things would have been different

Flat Baroque features early classics like I Hate The White Man and Another Day. Plus you have Keith Emerson and the rest of The Nice on the riotous Hell’s Angels. You appear to be making yourself unclassifiable, unconsciously or not.

Yeah, on that album you have all the different arenas I was just talking about, except there’s not much in the way of jazz. That said, Another Day has a couple of jazz chords in there. The classical influence is really the odd one out in some ways, because that wasn’t what was happening in 1965 Soho. That had happened to me previously.

My dad used to listen to ice skating on the radio – seriously! – where they played things like Sibelius’s Karelia Suite and all kinds of classical music. A lot of it was upbeat and I gravitated to the emotion of it; that was going to really affect a young mind. So I was already carrying that with me and was ready to use it. As soon as I could afford to bring in strings, I did it.

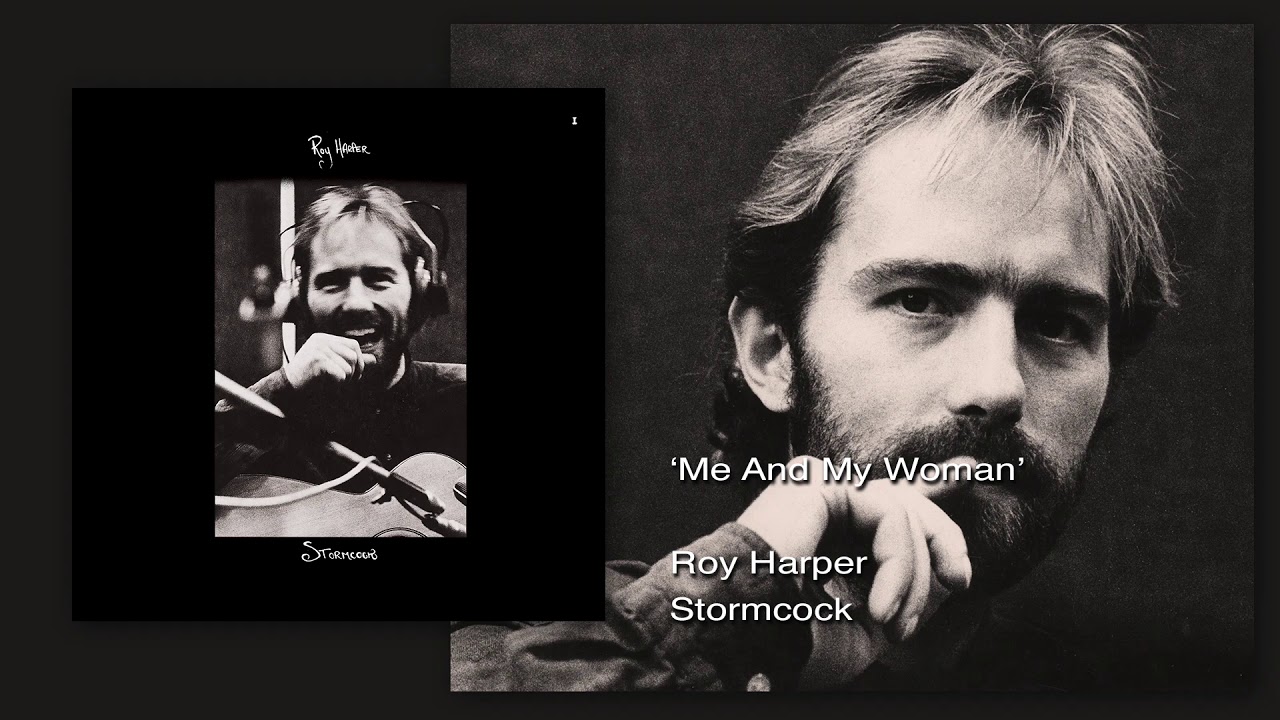

Which brings us to 1971’s Stormcock, featuring David Bedford’s great orchestral arrangements.

I felt the time was right to do what I really wanted to do. Unfortunately the record company, who came into the studio once or twice to take a listen, weren’t satisfied. They wanted a single and no single was appearing. They gave the first tapes out to Capitol Records in the USA and their guy didn’t want it at all, which effectively meant that it was a non-starter internationally.

They were hard-and-fast pop men. Anything that was selling in millions they got behind, but they weren’t into breaking new ideas. The ethic of Atlantic Records was completely different. A couple of years later, Led Zeppelin released a record with no singles and it was completely accepted. Unfortunately, I was tied to EMI.

The cops came in, told me I was there unlawfully, and, because there was a lit candle, arrested me for having a naked flame on a beach

So I was beside myself; distraught, to be honest. I knew Stormcock was a new direction for people to look at. If the record company had had faith in it, things would have been totally different. But I’m very grateful for it to have been finally accepted.

Me And My Woman embodies an ecological theme that’s recurred throughout your work. Was there a certain frustration in addressing those things when so few others were writing songs like that?

Yes – but there was also a joy in being able to do it, which levelled the playing field. Me And My Woman is me and my planet, me and the Earth. Fifty-odd years later, people are still asking the same question, but it’s got a lot closer to the bone now.

Those Stormcock songs were started in 1969 and were finished in the first few months of 1970. I’d spent a good bit of 1969 in California. One Man Rock And Roll Band was written on the beach at Big Sur, where two guys had asked me to look after their log cabin while they were away for a few weeks.

One day the door came down and the cops came in, told me I was there unlawfully, and, because there was a lit candle, arrested me for having a naked flame on a beach. They searched the place, but I’d buried my dope outside. I ended up in a cell in Monterey County Jail for about four days.

Anyway, Stormcock didn’t get released until 1971, which makes it sound like a totally different record. Because it’s 1969, and people don’t understand that. The year a record is released is important to the feeling that it generated, of a particular time. So for it to come out in 1971 is an affront – it’s an insult. Anyway, now that I’ve got that off my chest…!

I wanted commercial success, but on my own terms. And it just wasn’t available on my own terms

You shared the Harvest label with Pink Floyd for a time. Was there a kind of correlation there, artistically?

We were obviously friends, recording in the same place at the same time. So there was some kind of cognisance that we were on the same page. It did happen that, for whatever reason, I sang on their record and they played on mine [David Gilmour appears on The Game from 1975’s HQ].

That started a very long time ago, so we were in the same school at the same time. And the edges were bound to fray. We were bound to take from each other. I mean, David openly twice accused Roger, in front of me, of copying me.

Are you in touch with anybody from Floyd at all these days?

No. Not in that way.

Kate Bush once called you “the rebellious boy with the big heart.” You sang on 1980’s Breathing and she repaid the compliment on a couple of your songs. How was she to work with?

She’s a dream. She completely knows where she’s going with everything. She’s very naturally talented. I knew the family at one stage – I used to go around there quite a bit – and I think her brothers saw what talent she had when she was really young, and they were willing to nurture it. So she’s got all of the attributes and positives from that. She’s a very whole human being, which really shows in the way she handles her life.

Did you want to become a big commercial star like the people we’ve talked about?

I wanted it, but on my own terms. And it just wasn’t available on my own terms.

Not everyone may share my view on subjects, which may very often be considered as offensive. So the journey is solo

There’s a kind of artistic purity to that attitude.

Yeah, but it’s not quite like that, because you don’t set out to be some kind of saint. It’s just that I didn’t want to lose that direction of myself. I didn’t want to fall by the wayside in any way. I was a believer in myself, and there’s only so far I could take that.

But in other ways it’s telling, because the thought of having someone else on the stage with me is really questionable. How can I stand up there and say some of the things that I have to say as a singular entity, and have someone else there? It’s such a private thing.

Not everyone may share my view on subjects, which may very often be controversial to the point of seeming to be antisocial, and could even be considered as offensive. So how can that be shared? The journey is solo.

Has the stage always felt like a comfortable place to be?

Yes, because it’s somewhere to deliver a thought. Being onstage is a luxury; a treasure that tends to fill me with a certain humility. It’s a deep responsibility. A social thing. I’m carrying thoughts to others regarding code that I’ve attended to and developed over a period of a lifetime. It’s like a garden of thoughts that attach me to the deepest core of my own being, ideas and expressions that I carry with me. They’re like some kind of sanctuary.

When you’re not writing songs, you always seem to be doing something creative, whether it’s poetry or blogs or looking after your catalogue.

Yeah. One of the things that really takes time, actually, is when people write and ask to have records signed. Some of them get really extensive notes made over the top of the originals in big fat markers – especially the inside cover of Stormcock. So I’ve vowed to stop that, because it’s taking whole days from me!

You’ve talked before about recording new songs like The Man In The Glass Cage and I Loved My Life. Will there be a sequel to 2013’s Man & Myth?

There will; I’ve just got to concentrate again. I’ve been in the wilderness. I’ve spent the 40 days and nights – and it may as well have been 40 years – but I’m suddenly inspired again. I don’t want it to peter out. I’m willing to take it on to the end now and battle with it. I’m just this side of infirm! But the thing is, my mind isn’t. My mind is very kind to me. It offers me all kinds of pluses. I mean, what else am I going to do? Sit here and study the life and times of Henry III of England?

Inside, do you still feel like that teenager who started a skiffle band?

Oh yeah, I’m still a boy in my head. Unfortunately, maturation isn’t anything I’ve ever been interested in. Actually, that’s a fib, to be honest. In other ways I’m super-mature. The only trouble is I don’t know what ways they are!

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.