“It was beginning to feel like everyone’s mind wasn’t on the job… a feeling that there should be some hiatus”: Jethro Tull’s saddest, darkest album could have been even darker

Death, dysfunction and ecological disaster surrounded Ian Anderson as his changing world shaped a “forever tainted” record

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

With the 2019 release of the 40th-anniversary box set of Stormwatch – the album that some say completed Jethro Tull’s folk-rock trilogy after Songs From The Wood and Heavy Horses, Ian Anderson told Prog about the prescient record that was tinged with personal sadness.

Jethro Tull were given their name (that of an 18th-century agriculturalist) by Dave Robson, a booker at the Ellis-Wright agency who dealt with the young band. If they hadn’t played the Marquee club soon after the christening, Ian Anderson, who didn’t particularly like the name, reckons it would have been changed again.

But as the group’s frontman, writer of almost all of their material and the one who engaged most in the business side, Anderson went on to become synonymous with the name, to the extent that some people actually referred to him as “Jethro Tull.” In the States in the mid-70s, it was even shortened by some to the inappropriate and over-familiar “Jet.”

Many had noted that the figure in the cover painting of 1971 album Aqualung bears more than a slight resemblance to the singer, flautist and occasional guitarist. As does the depiction of Ray Lomas, the character in 1976’s Too Old To Rock ’N’ Roll: Too Young To Die!

But on Songs From The Wood (1977) and Heavy Horses (1978), Anderson was actually photographed; firstly done up to look like a character from Thomas Hardy’s The Woodlanders, and then like a Victorian ostler. These bucolic images broadly reflected his recent move to the English countryside and his practical interest in forestry and farming. He then acquired a salmon farm on the Isle of Skye.

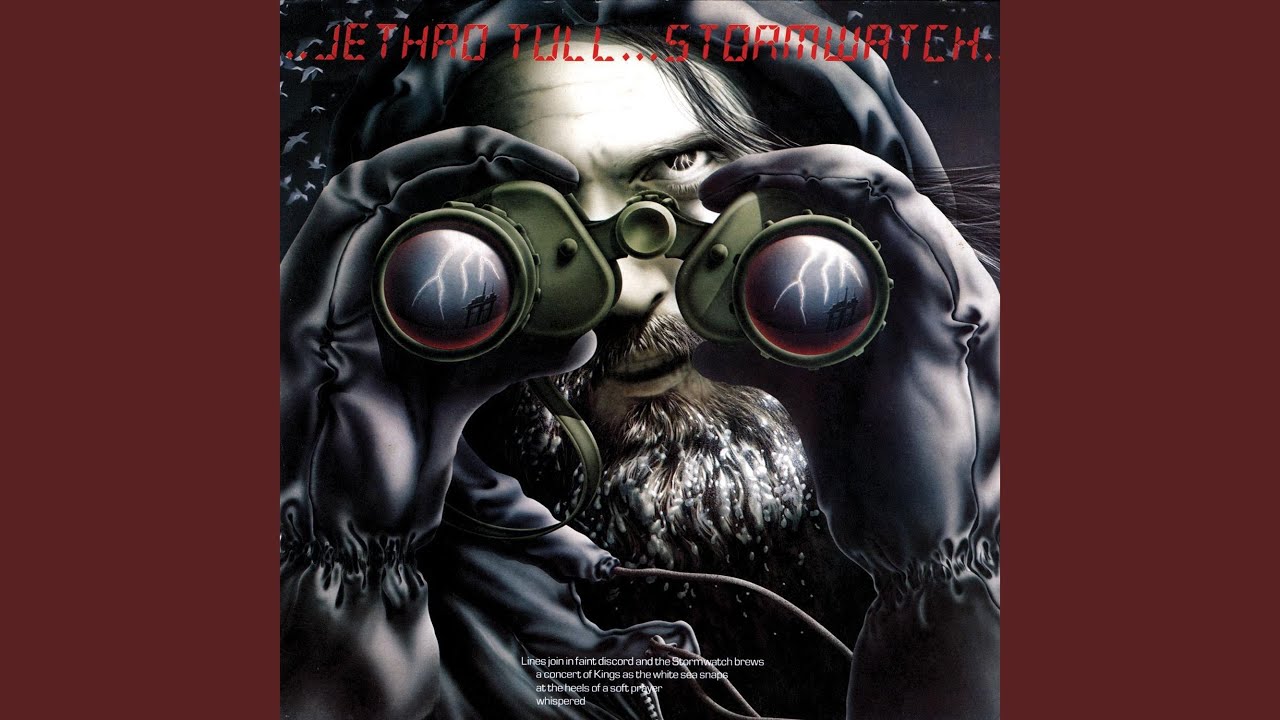

The cover of 1979’s Stormwatch features another Andersonian figure, his beard flecked with ice, set against a night sky, with forks of lightning reflected in the lenses of his binoculars. There’s a feeling of impending catastrophe, of benign natural forces veering to wildness.

Some claim it’s the final instalment in a kind of trilogy of folk rock albums. But while Stormwatch contains discernible folk elements, the album also includes tough dynamic rock tracks like Something’s On The Move. So what does Anderson think of the trilogy assessment?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“I never saw it that way, although everyone is entitled to come up with their own theories,” he replies. “Heavy Horses and Songs From The Wood are joined at the hip in some ways. With Stormwatch it was a swing to a darker expression and a lot of things to do with the environment. There were musical moments that were a little more esoteric, with some kind of spiritual thing going on – but overall it was a dark album.”

He notes that, by the late 70s, the prevailing view of the scientific community was that we could be heading towards a new Ice Age. Maybe that polar bear in the back cover really would soon be on Skye, helping itself to Anderson’s salmon. He’d embarked on the lyrical thread five years previously with Skating Away On The Thin Ice Of A New Day, on War Child, with its warning that ‘the story’s too damn real and in the present tense.’

In the intervening decades, scientific research has supported a different but equally alarmingly assessment: global warming. Like a growing number of people, Anderson feels urgent political action is needed on an international level. It’s a subject about which he is passionate.

“I hope we will live in a world where the villains of the piece – Donald Trump and others who might remain nameless – will be seen as having committed crimes against humanity, which is not putting it too strongly, for their stubborn and selfish lack of ability to take advice and act upon it,” he states. “It’s absolutely threatening to our future and, more importantly, to the future of our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

Jethro Tull are perennially cited as being quintessentially English, but Anderson was born in Dunfermline. And certainly a Celtic feel pervades some of the music on Stormwatch. “Here and there,” Anderson concurs, mentioning the instrumental Warm Sporran. The musicians also evoke the lonely grandeur of Skye on Dun Ringill, whose title comes from the name of an Iron Age hill fort set in spectacular coastal scenery.

On the tough, punchy North Sea Oil he examines the fossil fuel fields which, in the 70s, were seen as a kind of panacea for the UK’s economic problems. But Anderson was specifically asking: “What would it mean to Scotland to have its share of North Sea Oil, as opposed to the bit that Westminster gets?”

On Flying Dutchman he takes the cursed phantom ship that’s doomed to sail the oceans forever as a metaphor for a Scottish fishing fleet ‘gone to chase away the last herring, come empty home again’ due to depleted stocks and increasing marine toxicity. The turbulent, nine-minute Dark Ages – on which drummer Barrie Barlow sits tight on all the time changes, and Martin Barre occasionally produces flamboyant outbursts on lead guitar – sees Anderson poetically detailing an increasingly dysfunctional society.

Anderson explains the impetus behind his lyrics, with particular reference to Stormwatch, by saying: “The songs come from visual references most of the time – looking out of a bedroom window, or standing on a shore looking at oil rigs or fish farm cages. I’m interested in people in that landscape in the same way as actors on a stage. It’s not just the stage set. It comes alive when you populate it with people; that’s when the narrative begins.

“Or it might be a cultural landscape like Too Old To Rock ’N’ Roll: Too Young To Die! or in Aqualung, with imagery that I try to illustrate in words. I start off with visual images probably because, like many of my peers, I started off at art school.”

The 40th anniversary edition of Stormwatch features the original album remixed by Steven Wilson plus a 15-track “associated recordings” CD of finished songs, instrumental templates and quirky oddities, such as Lyricon Blues played on the Lyricon wind synthesiser. Other additions are rather more serious.

“I have said many times there’s nothing left in the tape vault, only to be confounded time and time again,” Anderson accepts. “And when I look at the songs that didn’t make it, there are a couple of things that are even darker; when you have a bunch of music you do try to balance it.”

Barrie felt very awkward, as I did. It was constantly in the back of your mind that this was not the way it was supposed to be

Would Man Of God fall into that category? “Exactly,” Anderson replies. “There were things that were a bit too pointy. I probably didn’t think that song belonged; it was bit too snidey about priests, although it was a specific example about an individual. I’m not in the business of being nasty to people – I think that was a bit too adolescent and critical.”

Stormwatch is, in Anderson’s words, “forever tainted” by sadness. Due to a congenital heart defect, bassist John Glascock was unable to play on more than three of the tracks that made the final cut. Although keen to contribute, he’d recently had major surgery; and he died two months after the album was released. And although keyboardist Dee (then David) Palmer’s closing instrumental piece, Elegy, was written for his own father, it feels like a fitting epitaph to Glascock – especially as it’s one of the tracks on which he played.

Anderson couldn’t bear to replace him with another bassist, feeling that it would have been like a “horrible rejection” – but they had to complete the album somehow, and so he took up the bass himself. “Barrie felt very awkward, as I did,” he says. “It was constantly in the back of your mind that this was not the way it was supposed to be.” But he adds: “We musically grew together in that process, and it’s evident on the quite detailed interlinking between the bass and the drums on Warm Sporran. It’s intricate stuff, almost jazz funk; I think we did a good job.”

Glascock’s successor – who played on one of the associated recordings – was former Fairport Convention bassist Dave Pegg, who’d continue to play with Tull on and off until 1995. In the box set he’s head on a concert recording from Holland in March 1980, which features some fine performances. It’s surprising, though, to hear Tull tackling Pegg’s Fairport Convention instrumental Peggy’s Pub. “When a new members come to the band we tend to give them a little spotlight,” Anderson explains.

Every few months I have a clear-out with set lists. It’s a bit heartbreaking, like falling out with old friends

But the line-up would soon disband, and as a studio statement Stormwatch marked the end of an era for what was essentially still Tull’s classic 70s team. With hindsight, it seems, the mood in the band was beginning to fracture. “But it didn’t feel like that at the time,” Anderson counters. “Although it was beginning to feel like everyone’s mind wasn’t necessarily on the job – [keyboardist] John Evan in particular, who I think had grown tired of the whole thing of touring and recording.

“Barrie was interested in doing other things, and David Palmer had extra-curricular activities, writing and arranging and doing orchestral stuff. So it was a feeling, at the very least, that there should be some hiatus.”

Are there any Stormwatch songs that Tull might include in their live set now? “We started playing Warm Sporran a few months ago – we’d never played it live at all,” Anderson says. “We also recorded a piece back then [on the associated recordings CD] called King Henry’s Madrigal. Its real title, as written by King Henry VIII, was Pass Time With Good Company. David Palmer put it forward as an instrumental tune and it was a bunch of fun. It’s a bit Blackmore’s Night, kind of spoof renaissance rock, and it’s in the stage set at the moment.

“So there are a couple of songs from Stormwatch that are out and about. But some songs on there are quite long, and where you put something in the stage set, you have to be thinking on what to take out. Every few months I have a clear-out with set lists, and it’s a bit heartbreaking, really, like falling out with old friends. You feel like you are cheating on a song by smooching with another one.”

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.