“If I’d put a live act together we’d have conquered the world. But it was a fear I had – what does a record producer do onstage? It was unfounded. We should have done it”: Studio veteran reveals big regret to a fan who’s now a big name himself

The Pink Floyd collaborator thought his career would last two years. But in the past five decades he’s had surprise hits, overreacted to a myth about tape, and made colleagues believe his ideas had been their own

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

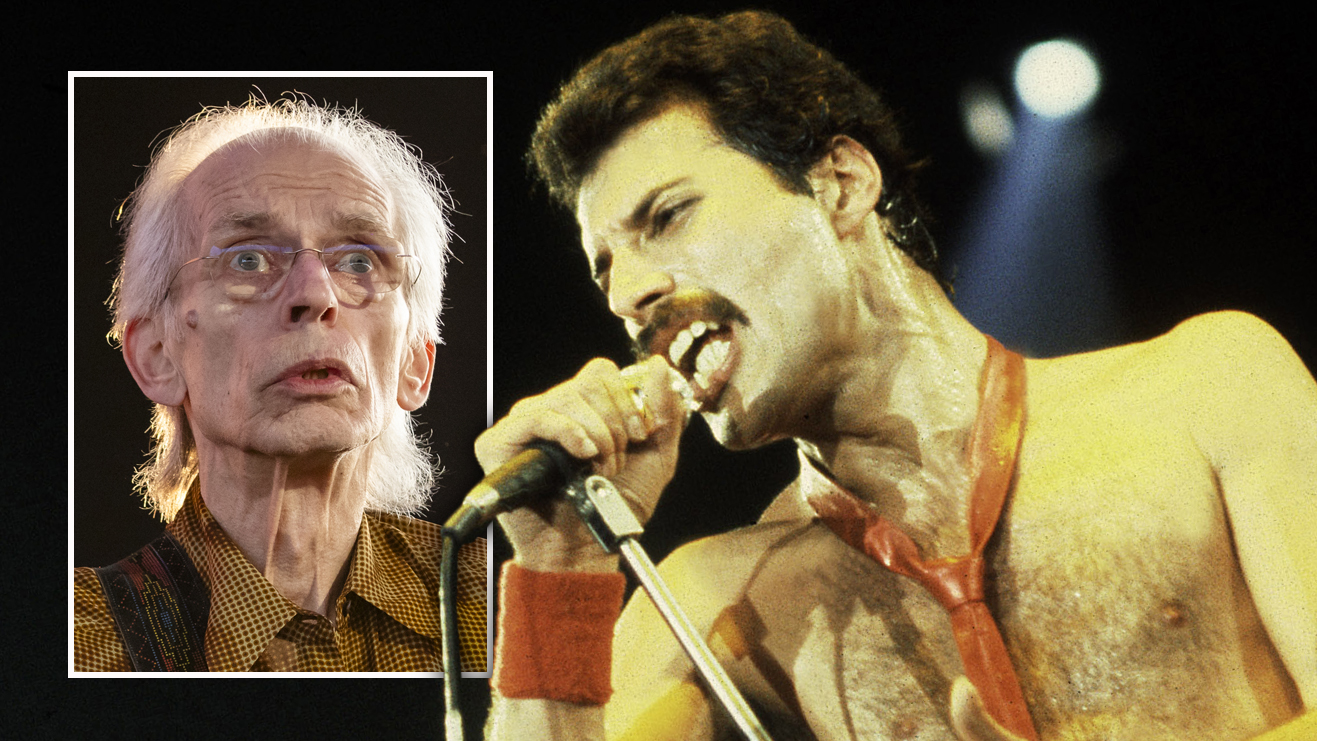

Never meet your heroes, the saying goes. But The Pineapple Thief’s Bruce Soord has never been one to follow the crowd, so when Prog asked if he’d like to interview Alan Parsons about 2023’s Alan Parsons Project box set for The Turn Of A Friendly Card, he leapt at the chance. Here’s what happened when Bruce met Alan (virtually).

On a Thursday night in February, Bruce Soord is about to chat to one of his musical heroes, Alan Parsons, over Zoom. Prog sits in to chaperone The Pineapple Thief producer-frontman and The Beatles and Pink Floyd producer-performer in case either of them faint. But once conversation has commenced, focusing on the 1980 Alan Parsons Project album, The Turn Of A Friendly Card, just re-released in expanded form – the pair are swapping trade secrets and away.

Parsons holds up the latest issue of Tape Op mag to debate musical terms with Soord, who admits, “As a 14-year-old, the Alan Parsons Project was my little secret, which made me a bit of a weirdo at school!” Thankfully, Parsons laughs. It appears this is a gamble that’s paid off.

Bruce Soord: In 1979, when The Turn Of A Friendly Card was recorded, the studio was a very different place. For a start, you had to use tape! Is there anything about that time you miss?

Alan Parsons: Very, very little! The tape machine had to be lined up every day, and so much time was spent winding back from the end of the song to the beginning. I don’t miss that much, but I did enjoy the period, and, of course, the sound of tape.

BS: In 1979 the primary format was vinyl. Was your album formed with the concept of an A-side/B-side in mind?

AP: Very much so, and cassettes were two-sided so you knew the gap was crucial, and a part of the decision-making process for how long, and in what order, the songs were.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

BS: I read that the record was recorded in two weeks, which seems incredible!

AP: You’re the second person to say that in an interview! It could have been about eight weeks, but we never did more than a couple of weeks at a time.

Eric Woolfson and I were both living in Monaco with our families and commuting between there and Paris, staying in a hotel in Montparnasse. We’d work during the day, go out to amazing restaurants, have a few drinks and return the next day. Then we’d come back home, recuperate, or work on further demos and new material for the album.

BS: One of the reasons you agreed to engineer Steven Wilson’s The Raven That Refused To Sing in 2013 was because they were recording as a live band. Was this something you always did with the Alan Parsons Project – did it feel like a band?

AP: Yes, it did; although apart from Eric and myself, they were all hired session players. When we were doing the backing tracks it was David Paton on bass, Ian Bairnson on guitar, Stuart Elliott on drums and Eric on piano. I always liked to have the band playing just to feel how the structure of each song was working.

They were fun to work with and all really great musicians; particularly Ian, who was responsible for the overall sound of the Project. It would have been substantially different if it hadn’t been for him.

BS: What was it like to be in a room with Alan the producer?

AP: I regarded it as a team effort. If you’re too much of a dictator in the studio you make yourself unpopular. You have to encourage everybody to pitch ideas, and you filter them and keep the good ones. And even if something is my idea, you have to make them think it was their idea!

BS: One thing I loved about the Project was the use of so many different session players. To hear Chris Rainbow’s solo vocal mix of Nothing Left To Lose on the latest edition was a revelation. Didn’t you call him the one-man Brian Wilson?

AP: The one-man Beach Boys! He was remarkable, considering he had a really bad stammer. He was note-perfect, but when the tape stopped he’d start stammering again. We got used to it. He was such a talented singer and he came up with incredible parts. I think Nothing Left To Lose was a moment of glory for him.

BS: The whole disc of Eric’s early piano and vocal demos is interesting. DId he turn up with a bag full of cassette tapes?

AP: The cassettes were for himself. When he played a song for us for the first time he’d sit at the piano and sing it – probably just to me at first, then we’d get the band involved.

I would say, “Oh, this bit goes on too long, we need another chorus,” and all that stuff. Sometimes we’d turn the song inside out and sometimes it would be very close to the demo. I remember with Time, his second chord made it sound very similar to Floyd’s Us And Them, so that had to go. That was the process.

BS: Then there’s The Gold Bug demo. Is that you jamming with a drum machine?

AP: Yeah, I did that in my apartment in Monaco.

BS: It’s only when you add the delay to the keyboard that it turns into the part we all know.

AP: That’s a sort-of trade secret of mine – you find a part then you put delay on and it changes it completely. That happened on Sirius, believe it or not. I stole that trick from Pink Floyd. Their song One Of These Days uses it. The bass part is really simple but with the delay it becomes something else.

BS: It must have been really nice to see and hear the songs come together with everyone involved.

What I’ve told countless interviewers is that we are progressive pop, not progressive rock

Alan Parsons

AP: Yeah, it was a fun album to make. We would start mid-morning, work on through, get a takeaway for lunch and then all go out and have a sumptuous dinner in the evening. Towards the end, we had to go back to the studio because the deadline was approaching, but usually we’d have a few drinks and hit the sack.

BS: One thing that defines APP for me is the strings of Andrew Powell. I don’t think anyone else was doing it quite like you were in rock music.

AP: Thats off to Andrew. I discovered him when I was working with Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel. He did great arrangements for the songs Death Trip and Sebastian. He’d done a fantastic job on our first album, Tales Of Mystery And Imagination. He was the only arranger I worked with – and, of course, he did the arrangements for Al Stewart’s Year Of The Cat, which were magnificent. He was a big part of the sound of the Project.

BS: The strings were recorded in Munich. Is it true that [vocalist] Lenny Zakatek drove the master tapes there from Paris?

AP: Yeah, we were terrified because there was this old wives’ tale that tapes got wiped in X-ray machines at airports, so we had Lenny and a record company guy drive them from Paris to Munich.

BS: The strings sound completely locked in with the band. How did you do it? Were you at the session?

AP: Oh yes, I was always there! The studio in Munich had all German players, and Andrew speaks good German. Back in 1979 there weren’t enough headphones to go around so the tracks would have been played through a speaker.

There was always a battle with the orchestra; the leader was always asking for more volume. Andrew would get the click track but we couldn’t put that out through the speakers because it would have been heard on the final version.

The syncopation in our music confused classical players quite a lot – they found it quite challenging on occasion.

BS: I’ve got to ask – would you call APP progressive rock?

AP: What I’ve told countless interviewers is that we are progressive pop, not progressive rock.

BS: Which brings me nicely to the ‘hits’ from the album. Were they a surprise?

AP: We were very surprised, particularly with a ballad, Time – it was slow and somewhat dreary; Games People Play is pure pop.

BS: How did having hits change things for the Project?

AP: The singles success translated to album success and Clive Davis [the head of Arista] was always looking for the next single from successive albums. Eye In The Sky was the big one, I suppose.

BS: Friendly Card sold two million copies in the US alone, and without the commercial benefits of touring.

AP: We didn’t have a live act, so the only promotion that we could do was go to all the big cities in the US and play the album to the press and radio stations. I think if I’d put a live act together we could have conquered the world.

BS: Why didn’t you play live?

AP: It was a fear I had. What does a record producer do onstage? We discovered it was sort-of unfounded – as long as I could play a few chords on guitar and do a few “oohs” and “ahhs,” that was considered valid as a live act. We should have done it, but we didn’t.

BS: Do you regret that?

AP: Absolutely, yeah. But had we played live I wouldn’t have had time to make other people’s records. The other reason was the orchestration. We’d have had to take an orchestra on the road, which didn’t make financial sense. But by the time Try Anything Once came along in 1993 – the first non-Project album – sampling keyboards could get a good representation of the orchestral sounds.

[Parsons took up touring later in his career and continues to hit the road.]

BS: You’ve been in the record industry since joining Abbey Road in 1968. It feels to me as if you’ve lived and worked through a revolution.

AP: I’m just glad to still be around! The normal lifespan of a record producer is maybe two years. And The Dark Side Of The Moon has passed 50. So I’m still here!

Jo is a journalist, podcaster, event host and music industry lecturer who joined Kerrang! in 1999 and then the dark side – Prog – a decade later as Deputy Editor. Jo's had tea with Robert Fripp, touched Ian Anderson's favourite flute (!) and asked Suzi Quatro what one wears under a leather catsuit. Jo is now Associate Editor of Prog, and a regular contributor to Classic Rock. She continues to spread the experimental and psychedelic music-based word amid unsuspecting students at BIMM Institute London and can be occasionally heard polluting the BBC Radio airwaves as a pop and rock pundit. Steven Wilson still owes her £3, which he borrowed to pay for parking before a King Crimson show in Aylesbury.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.