"I was in the hotel with Joni Mitchell, but then the helicopter pilots decided they wanted more money": The last interview with Terry Reid

Touring with Marvin Gaye when he was 16, being pals with Aretha Franklin, turning down Led Zeppelin, making wonderful solo albums… Late British singer/guitarist Terry Reid had quite the life

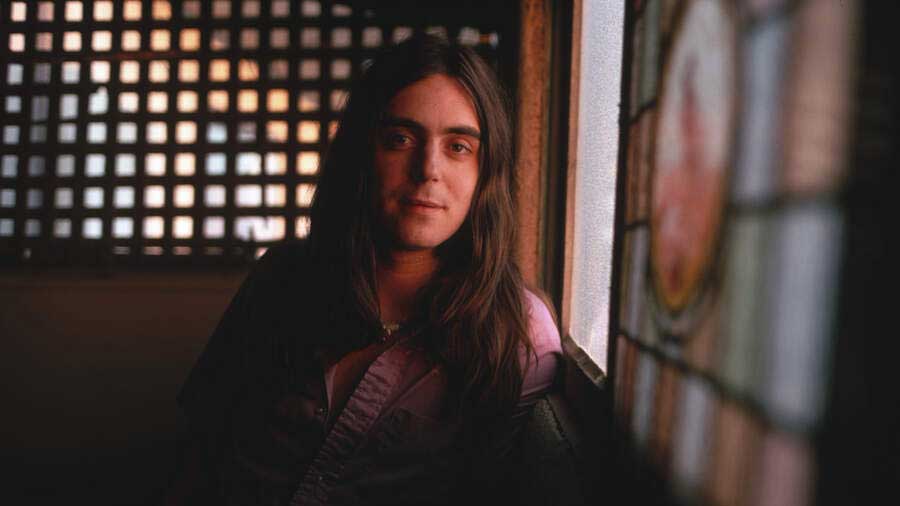

When Classic Rock spoke to Terry Reid in June this year, the veteran singer-guitarist was looking ahead to his biggest tour in years, a month-long trip around the UK and Europe, due to start in early September. He was on terrific form. By video call from the Californian home that he shared with his wife Annette – “We’re in La Quinta, surrounded by palm trees. It’s beautiful. I love it out here in the desert” – Reid took us on a fabulously digressive journey through the highlights of his long career.

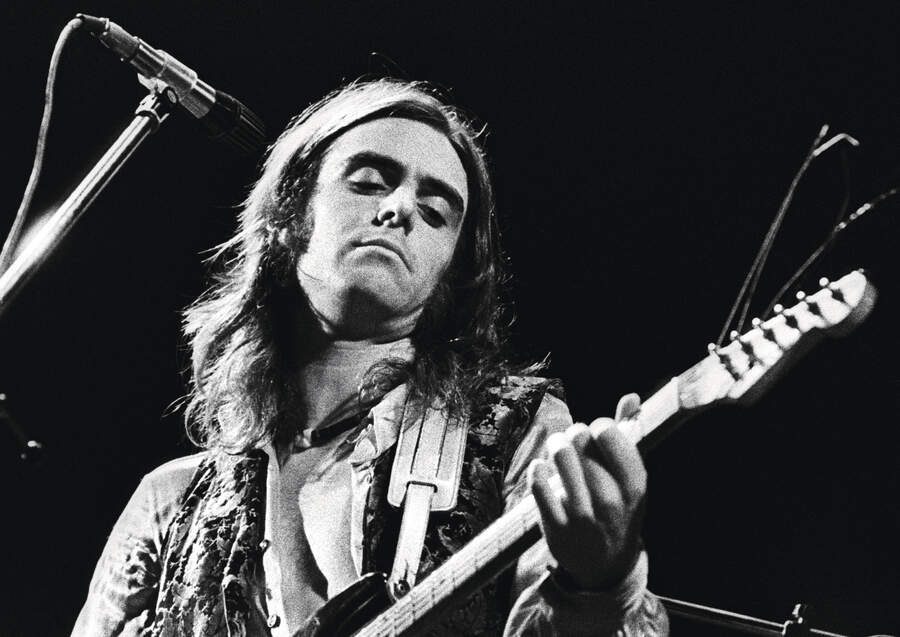

Despite being resident in the USA since the early 70s, Reid’s speaking voice still carried a strong East England snap. Wearing a white sleeveless T-shirt, and a chunky pendant hanging from his neck, the 75-year-old looked every inch the rakishly-aged rock star. He was quick to laugh – a cackle born of a mischievous spirit that had endured since his childhood in post-war Huntingdonshire.

Reid caught his first break while a teenager in 1965, when he accepted the offer to join Peter Jay And The Jaywalkers. But it was as a solo artist that he truly shone. Lauded by his peers, Reid was blessed with an extraordinary voice, capable of the most emotive white soul or searing R&B, as powerful as anything by 60s better-known contemporaries Steve Marriott or Stevie Winwood. He was nicknamed ‘Superlungs’, after the seismic version of Donovan’s song Superlungs My Supergirl that opened his second solo album, 1969’s Terry Reid.

In 1968, Jimmy Page wanted Reid to front the new band he was forming, The New Yardbirds. But, already committed to US tour dates with the Rolling Stones, Reid had to turn down the offer.

Management disputes, bad luck and record label troubles clipped Reid’s wings during the 70s, a decade in which he nevertheless hit creative heights with the loose, multi-faceted album River and the immaculate Seed Of Memory.

While in later years Reid favoured live work and the odd collaboration over being in the studio, when we spoke to him he had new songs on the go. Reid’s energy was flagging by the hour-and-a-half mark of our interview. We had planned to catch up again before the tour, but, sadly, it wasn’t to be. Having had treatment for cancer, he passed away on August 4.

This, then, is the last interview Terry Reid ever gave.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Was it always going to be a musician’s life for you?

I can’t think of me being anything else. The only thing I was interested in at school, other than art class, was throwing pots. I actually could’ve got a scholarship to study pottery. My dad was a car dealer and wanted me to be a mechanic or an engineer. But it wasn’t my game at all. He eventually said to me: “I suppose we can forget about you getting your hands dirty”.

Growing up, I believe Tommy Steele’s Singing The Blues was a catalyst of sorts?

You’ve nailed it. I went to see him at the London Palladium with my parents. That was the first rock’n’roll concert I ever saw. Tommy Steele had it all for me. He was like a good vibe. I’d already got the singing bug, but he set me right off – “I need a guitar now!” Years later I was having a beer with Steve Marriott and said: “You know who you remind me of? Tommy Steele”. He had the same carefree attitude, and would do anything for his fans. Steve thought that was the biggest compliment in the world.

You were fresh out of school when you joined Peter Jay & The Jaywalkers in 1965. What was that experience like?

The year before I joined, they’d toured with The Beatles. Then in ’66 we supported the Stones on a package tour. That’s when my whole life changed. It wasn’t just about playing music, there was more to it than that. Insanity and danger. I thought: “You could get hurt here”. There was a riot at the Albert Hall gig. I saw the clips on the news later on. All these kids mobbed the stage and the Jaywalkers and the Stones ran for the only exit.

So it was interesting, but also so much fun. I was on the bus with Ike and Tina Turner, who were also on that tour, travelling up and down England. Tina and the others were always singing on the bus. R&B songs that I’d grown up on - The Four Tops, Marvin Gaye and so on. Imagine what effect that had on a 16-year-old kid. You’ll never be the same again after experiencing something like that.

Your good friend Graham Nash, then with The Hollies, introduced you to producer/manager Mickie Most.

It was a great idea at the time, but things went a bit haywire when we got into it. Mickie started off by wanting to make a Tom Jones out of me. Now don’t get me wrong, I love Tom Jones, but it was the suit and bow tie and everything. We’d start doing clubs, and I’d have a tuxedo on, this whole image that didn’t fit me.

Was it his idea to cover Donovan’s Superlungs My Supergirl?

Yes and no. Me and Graham Nash would hang out with Donovan at his place in the countryside. One day we’re sitting there, and Don says: “I’ve written this song called Super Lungs, about a 14-year-old schoolgirl who just wants to sit there rolling joints all day.” So he gets out his guitar and plays it to us. Then he goes: “Terry, you’d be great singing that!” I asked why Don wasn’t doing it and he said: “Mickie Most doesn’t want me to do it. He thinks it’s bad for my image.” Now, Donovan rolled the best joints you ever saw in your life. They were like cannons. So we were all laughing, thinking this was a joke.

Then a few days later, I go into Mickie’s office, which he shared with Peter Grant, and he says: “I’ve got a perfect song for you that Donovan’s just written. It’s called Super Lungs.” I pretended I hadn’t heard it, and made them explain what the whole thing was about. I looked at them both: “Don’t you think it’s bad for my image?” Peter just started laughing. He said: “No, it’s a hit!”

One of your earliest compositions was 1968’s Without Expression, which was soon covered by The Hollies, and then by CSNY as Horses Through A Rainstorm. It was also done by REO Speedwagon and John Mellencamp.

When my mother passed away a couple of years ago, we went back to England and went through everything in her house. She had loads of stuff. She’d even kept all my school homework things, and pictures and paintings. So I’m flicking through some pages, and, in very small writing, I find the lyrics to Without Expression. Of course, there’s a date on there, so I figured out I was twelve or thirteen when I wrote it. I was in shock. By the time I recorded it I was seventeen or eighteen.

By the late 60s, Reid’s reputation had grown apace. His 1968 solo debut album Bang Bang, You’re Terry Reid (then issued only in the US) roughly coincided with the invite from Jimmy Page to front The New Yardbirds, soon to morph into Led Zeppelin. Having turned down the offer, he recommended two members from Band Of Joy, a Midlands group who’d recently supported him in the UK. Within a year, the in-demand Reid had also rejected offers to join the Spencer Davis Group and Deep Purple (pre-Ian Gillan), preferring to concentrate on his solo career.

In 1968, fast-rising soul singer Aretha Franklin famously declared: “There are only three things happening in England: the Rolling Stones, The Beatles and Terry Reid”.

I actually got to be friends with Aretha, which I could never quite get over. On the inside she was very warm and tender, but you didn’t mess with that woman. The lady was a force. She drove [label head] Ahmet Ertegun crazy at Atlantic. Obviously she’s the greatest singer I ever heard in my life. So when I finally got to meet her I’m thinking: “Do I tell her how much I love her voice?” We were talking one day, and she suddenly just stopped, gave me a funny look and went: “I never figured you loved me as much as you do. But you really do, don’t you?” And I burst into tears.

Given that this is an interview for Classic Rock, I have to mention the whole Led Zeppelin thing…

I’m not interested in that. There’s nothing more to say about it, y’know.

Okay, I understand. But if you’ll indulge me, I just wondered whether the chemistry between Robert Plant and John Bonham was immediately obvious to you?

They were frigging perfect. Nobody looks at it like a group concept. If Robert Plant hadn’t have joined the group, then you wouldn’t have had John Bonham. For me, there’s only been two or three drummers that could even stand in the same room with Bonham. If you want a rock’n’roll drummer, don’t fuck around. Get one that’s heavy-duty. Not only that, John Bonham had the most incredible timing. Robert could sing all those phrases that Jimmy Page played on guitar, which makes it very musical, but John Bonham really gave the group its meat.

My whole comment now on Led Zeppelin is God bless them. It was a magic thing that happened. And ten billion people can’t be wrong. And you helped make it happen. Yeah. Put it this way, I was part of the team that made it happen.

You played the first Glastonbury Festival, in 1971. Didn’t you get high with David Bowie?

That was funny. This was before Ziggy, when he was reading poetry and playing this Hagstrom 12-string guitar that sounded horrible – and he agreed. The night before the festival, everybody was getting loaded at [festival site owner] Mike Eavis’s cottage, waiting for the sun to come up. We were just having a good old time.

I saw an interview with David Bowie years later and they asked him what he remembered of Glastonbury. He said: “Not a hell of a lot. I was in the cottage with Linda Lewis and Terry Reid, and talking to Terry all night long. But for the life of me I can’t remember what we talked about”. He was lovely, David. A real sweetheart.

And was it all good vibes?

Oh yeah. Everybody was really into it and out of their brains. It was a freedom festival, a nice place to go for like-minded people. There were various chemicals around, so you’d see someone go floating by. I’d played a few of the really big festivals while I was over in the States, like the Atlanta Pop Festival. When Woodstock was on I was in New York and up for doing it. In fact I was in the hotel with Joni Mitchell. But then the helicopter pilots decided they wanted more money, so they went on strike. It ended up with me sitting there with Joni while she watched Crosby, Stills & Nash on TV, which led to her writing Woodstock. That was a strange moment.

Having met American multi-instrumentalist David Lindley in 1969, Reid began expanding his musical palette. Funk, abstract jazz and sinuous samba grooves all found their way into his majestic album River, which – due largely to contractual litigation with Mickie Most – wasn’t released until 1973. Puzzled by the album’s varying mood shifts, Atlantic dropped him soon afterwards. By then Reid was already living in California, and its harmony-rich West Coast vibe invested 1976’s Seed Of Memory with much of its timeless charm. Alas the album never stood a chance, with parent label ABC going bust a week later. A similar fate befell 1979’s Rogue Waves, due to Capitol’s financial troubles.

Exiled Brazilian legends Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso often visited you in England. Did that experience feed into the making of River?

Yeah, it did. That was another life-changing experience. Gilberto was always great with me: “You can do this, Terry. Look.” He’d be showing me these samba chords, which are just whole other shapes. It all sounded wonderful, and it took me the longest time to get it. He thought it was hysterical. Gilberto liked to get out of London, so he’d stay at my cottage in the countryside, in this little village. Then he came up with Caetano, who was the biggest star in Brazil, and after that people like Airto [Moreira, drummer]. Every time he came up he’d bring more people.

It became like a community. I ended up with ten Brazilians in my house for a two- or three-day period. I had a big inglenook fireplace and we’d pile on the logs - me and David Lindley and these incredible Brazilian musicians – and sit there playing music for hours, until the sun came up. That’s when you really learn things. There’d be all hell going on: congas, berimbau, cuíca , guitars, singing.

The local policeman, who I’d known since I was a kid, knocked on the door one morning: “Terry, we’ve had a couple of complaints. Are you having a tribal gathering here?” I invited him in, made him a cup of tea and introduced him to all these Brazilian people. I’ve never seen an Englishman so confused in my entire life.

Did those get-togethers partly inspire the sound of River?

Absolutely. I had plans to do more stuff with Gilberto, and go into the studio to record them, but things were a bit of a mishmash at that time. We were finally making a rock’n’roll album, with a peppering of Brazilian-influenced things, like [title track] River. I never got to really cut River in England with Gilberto, even though I wrote it in that cottage, with us all. I ended up doing it with Willie Bobo, a Puerto Rican timbali player who’d played with Count Basie. We did that in Hollywood, up at Wally Heider’s studio.

The other songs we did were with Alan White and David Lindley. But then the whole band went haywire. Some went to America, and Alan joined Yes, so I moved to the States. I thought I could get more done over there. It was getting a little crazy at home.

River is such a wonderful album, especially when it comes to those abstract, slightly jazzy elements.

Yeah, that record is a time in space. It’s not a musically prepared, rehearsed, well-worked-out album. It’s a whatever-comes-next kind of thing. It’s whatever you’re feeling in the moment.

You reunited with Graham Nash for 1976’s Seed Of Memory, which he produced. Were you looking for him to shape those songs in a certain way?

They shaped themselves, to be honest. I’d moved up to the mountains, on the Ventura County line. It’s a Western scene, like moving into a cowboy movie. Actually, it’s an Indian burial ground. And it’s so peaceful and quiet. Bob Dylan ended up buying a property nearby. Garth Hudson from The Band lived up there too. I wrote most of the songs there, stuff like Brave Awakening and Seed Of Memory. I was totally disillusioned with record companies. I didn’t want anything to do with them. So I called Graham, to see whether he thought these songs were a load of rubbish or worth pursuing. He goes: “Yeah, send them over.” So I did that, then didn’t hear anything for a couple of weeks.

One day he calls me up: “So I got you a deal with ABC Records. I’ve already called a few musicians that we know. We’re gonna make a record and I’ll produce it with you.” The next thing, we’re in the studio, and Graham says: “Terry, this is your album. It’s going to show you as a singer and really put your style out there. No bells and whistles.” The first song we do is Brave Awakening. At the end he comes in, stands next to me and goes: “Y’know what, I hear a great harmony on that.”

We ended up with him singing all over the record. There’s no way he could stay behind that window. It was just impossible. But it was such a pleasure to make. Everything felt so easy.

Considering how great both of those solo records are, and how the record business seemed to conspire against you at the time, did you ever question what you were doing?

No. I devoutly believed in what I wanted to do. I just needed somebody to let me bloody do it, or get behind the thing. It was like: “Are they going to get behind this, or not? Is this going down the tubes?” But it’s no good doubting yourself. If that’s the case, you shouldn’t be playing music in the first place. I just got so fed up with record companies. There were only a couple of people, like Ahmet Ertegun [at Atlantic] and Chris Blackwell [at Island], who I totally adored. Then there were all these business people that hadn’t got a bloody clue.

So here you are today, making music at your own pace. Have you been writing lately?

Yeah. I’ve written a bunch of new songs, but haven’t recorded them yet. I’ve been going through a lot of the stuff I have here. I built an analogue studio in a room in the house. It enables me to record on eight-track, which I really like because it sounds very warm.

What are the new songs sounding like?

Varied. Some lean towards country, but they all mostly lean towards R&B. I’ve just got to spend some time getting down to them and doing it.

Do you ever get homesick for the UK?

Not really. But you get funny little twinges when you’ve lived in another country as long as I have. It’s all those little personal things, like the orchard I grew up with in the countryside, in Bluntisham. That becomes very nostalgic. And walks down to the river, where there’s a nature reserve. When the birds migrate it’s just unbelievable at dawn, watching them all flying in. You remember all those things from when you were a kid. And it’s the same every time I go back to London, having lived there for several years. It’s changed so much, but I have so many warm memories of the place.

Online Editor at Louder/Classic Rock magazine since 2014. 40 years in music industry, online for 27. Also bylines for: Metal Hammer, Prog Magazine, The Word Magazine, The Guardian, The New Statesman, Saga, Music365. Former Head of Music at Xfm Radio, A&R at Fiction Records, early blogger, ex-roadie, published author. Once appeared in a Cure video dressed as a cowboy, and thinks any situation can be improved by the introduction of cats. Favourite Serbian trumpeter: Dejan Petrović.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.