“People came up to us after gigs and said our music terrified them." The saga of Hawkwind's Space Ritual

"Dim visions smoked his brain. Pictures of people standing and screaming and a band playing loud shrieking metal music…" – Extract from The Saga Of Doremi Latido Fasol

It’s November 1972, and something extraordinary is happening in the sleepy Norfolk market town of King’s Lynn. The Corn Exchange venue is packed to the rafters with East Anglian heads and freaks, along with the local chapter of Hells Angels and a smattering of terrified teenyboppers.

It’s the first night of Hawkwind’s Space Ritual tour, an event that’s been trailed by the band for more than a year now. It’s the culmination of three years of intense gigging around Britain and Europe, a multimedia sci-fi spectacular featuring dancers, space-age poetry, the most ambitious lights and visuals show on the circuit, and more than two hours of continuous, mind-expanding music.

This was the year that David Bowie became Ziggy Stardust and incorporated mime and kabuki theatre into his shows; the year that Peter Gabriel started to recite strange stories between Genesis songs and wear a fox head and dress onstage; the year that Pink Floyd first experimented with quadraphonic concert speakers and played gigs with a ballet company.

Yet none of these innovations rivalled the sheer visceral, multicolour trip of the Space Ritual. It was unlike anything experienced before in the nation’s provincial music halls, a gathering of the underground tribes with Hawkwind as their cosmic spirit guides – not just a show, but yes, a ritual as well.

The Space Ritual tour is one of the great highlights of Hawkwind’s ongoing 53 years-and-counting mission to the outer reaches of space rock, with the Space Ritual album – released in May 1973 and regularly touted as the greatest live record of all time – their highest-charting LP. But the story of the Space Ritual had begun 18 months before at the tail-end of 1971 with the release of the band’s second album, In Search Of Space.

An integral part of that album was its unique design, which featured a die-cut sleeve that opened up to reveal inside The Hawkwind Log, a 24-page booklet telling the disjointed story of the “spacecraft Hawkwind” and its journey to save the Earth. The man behind this startling package was Barney Bubbles, who would go on to produce a complete visual identity for Hawkwind, while the writer of the …Log was poet and conceptualist Robert Calvert, who officially joined the band as their irregular frontman following ISOS’s release.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Both men were absolutely key to the formulation of the Space Ritual, with ISOS being just the first chapter of their recasting of Hawkwind as mankind’s musical saviours from the stars, psychedelic freedom fighters inhabiting a science fictional universe. And it wasn’t long before their thoughts turned to how this developing mythos could be incorporated into Hawkwind’s live performances. The band’s shows were already becoming legendary for their immersive, trance-inducing quality, but Calvert in particular was interested in turning them into a new type of rock theatre – or rather, space opera.

Talking to Melody Maker in November ’71, he said: “The basic idea of the opera – for want of a better word – is that a team of starfarers are in a coma, a state of suspended animation, and the opera is a presentation of the dreams that they’re having in deep space. It’s a mythological approach to what’s happening today… the mythology of the space age, in the way that rocket ships and interplanetary travel are a parallel with the heroic voyages of man in earlier times.”

Speaking at the same time to NME, anarchic saxophonist Nik Turner had already embraced the idea. “I don’t think our music had a real direction until Bob got this space odyssey together,” he observed. “It was just freaky, with us enjoying ourselves. The album [ISOS] was a coming together of ideas and the odyssey is a progression from that… Just tell people to come have their minds ripped apart!”

While also a big fan of sci-fi and fantasy, bandleader Dave Brock was more concerned at this point with the latter sentiment, Hawkwind having definitively progressed from wanting to “levitate minds in a nice way” (as the sleeve notes to their first album stated) to becoming the sonic equivalent of “a black fucking nightmare” (as Lemmy memorably put it). In the same NME piece, Brock said, “People come up to us after gigs and say our music terrified them. Because they can’t cope with it, they get frightened… I think if we had more time to get it together, we could induce mass hypnosis in an audience. I’d certainly like to experiment with that.”

However, time to get things together was at a premium as 1972 dawned, with the Space Ritual concept put on the back burner as Hawkwind prepared to take on their busiest year yet. It would eventually see them playing more than 150 gigs, their commitment to bringing their unique brand of countercultural ramalama to every corner of the country (not to mention mainland Europe) undimmed.

But while they were playing bigger venues and pulling ever larger crowds, Hawkwind’s roots as a community band were still strong, and it was at a benefit gig at London’s Roundhouse in February that the next step towards turning the Space Ritual into reality was taken.

Even by the underground’s standards, the Greasy Truckers Party was a shambolic affair, with the sold-out show interrupted halfway through by a power cut, which necessitated the venue being cleared for a couple of hours. When the audience returned, its size had swelled considerably. Doug Smith, Hawkwind’s manager at the time, remembers: “The place was packed. People sitting two to a seat or on each other’s laps, and obviously over capacity. I persuaded those in charge to let them all remain if we got them all to squeeze up – I think they realised that if they tried to clear out the extra people, there’d be a riot!”

In the meantime, Hawkwind had prepared for their performance by getting completely off their heads, with the cocktail of speed, downers and acid favoured by Lemmy and electronics berserker DikMik proving to be particularly debilitating. The power was also still playing up, which meant that one of the band’s roadies had to manually hold the main breaker switch open throughout the gig to keep the electricity on.

Despite these challenges, Hawkwind managed to deliver a surprisingly cogent set, with two tracks – Master Of The Universe and Born To Go – recorded and released on the subsequent Greasy Truckers Party LP, a limited-edition album that quickly sold out and became a much sought-after collectors’ item. Yet these weren’t the most important recordings from the show.

Over the past couple of months, a new song had entered Hawkwind’s live set that Doug Smith had already earmarked as a potential single – its title was Silver Machine. The version of it recorded at the Greasy Truckers show was rough and ready, with Calvert often missing the microphone and garbling his words, but it had an undeniable energy.

Smith held it back and reworked it with the band at Morgan Studios. Andrew Lauder, then head of A&R at the band’s label United Artists, remembers: “Doug pretty much did [the single] off his own bat. He came in with a tape after it’d been worked on in the studio, and said, ‘Have a listen to this.’ And I said, ‘Jesus, what have you done?!’”

Silver Machine was transformed from a loose cosmic jam into a monumental slab of sci-fi boogie, the post-production cladding its fuselage in steel and mounting a new engine on each wing. But key to its success was the replacement of Calvert’s wayward vocal with an imperious revoicing from Lemmy, bellowing the opening ‘I!’ like a man asserting his will to power.

Lemmy maintained he was only allowed to do the vocal after everybody else had had a go, but Nik Turner told a different version of this story: “Lemmy claimed that everybody else was tried, and then he got the job. It’s actually bullshit. Lemmy was a person who was very forceful and pushy because he took a lot of speed. He got the job because he elbowed everybody else out the way! But I was happy with Lemmy’s rendition, it was actually very good, more the right shape for a pop song.”

And incredibly enough, a pop song was how Silver Machine was received when it was released as a single in June 1972. As the new release from the biggest cult band in Britain, it immediately started selling to Hawkwind’s legion of fans, but when it got on BBC Radio 1’s playlist, things really started to happen, with regular spins from establishment DJs such as Tony Blackburn and Jimmy Young. Even more incredible – certainly as far as the underground commentariat was concerned – a film of the band performing the song live was used to promote the single on primetime chart show Top Of The Pops.

Silver Machine was a bona fide phenomenon, with its appearances on TOTP in particular opening up a portal from countercultural west London into every front room in Britain, a televisual rallying cry for nascent heads and freaks around the country. Peaking for two weeks at No.3 in the hit parade, it remained on the chart for over three months, and eventually went on to sell a million copies around the world.

Silver Machine was also vital as the spark that finally lit the touchpaper of the Space Ritual, with the money it generated providing the financial muscle necessary for planning and preparations to begin, with UA also giving them an additional advance. One of the first things it enabled Hawkwind to do was finally buy some proper transport – a Mercedes van for the equipment and crew, and a Mercedes tour bus for the band.

There wasn’t any danger of the band’s new-found fame and money turning them into rock’n’roll superstars, however. On the contrary, Dave Brock was keen to stress that their credentials as a ‘people’s band’ remained strong. Speaking to Sounds, he said, “We’re not involved in the music business at all. We’re still doing exactly the same things, seeing the same people, still living round the ’Gate. There’s so much shit involved in the music business… We’re on the fringes [of it], like having a record contract, but only as long as we can do what we want to do.”

His response to the success of Silver Machine was also ambivalent, while still acknowledging that the demographic of the band’s fans – many of whom would go on to be the core audience for the Space Ritual – was changing. “It’s a bit of a drag because all the heads who used to come and see us usually turn up late, because they’re completely out of it, and of course now they can’t get in,” he said. “It’s good in a way too, because the average age of our audience has dropped to 14 or 15, and they probably get turned on to new things when they come to one of our gigs.”

The raising of the band’s profile post-Silver Machine led to two major shows. In August ’72, they played a prestigious headline gig at the Rainbow Theatre in London’s Finsbury Park, where free food was given out to all attendees. Unfortunately, the communal vibe was somewhat wrecked by 600 fans – presumably some of Brock’s latecomers – storming the barriers of the sold-out venue and forcing their way inside.

And in September, Hawkwind played the Oval cricket ground with Frank Zappa – in fact, the band came on after Zappa in the evening so their light show could be seen in its full glory. Doug Smith remembers: “They tried to turn the power off because Zappa had run over, and I stood in front of the generator with a hammer. The promoters had to get the police to remove me, and they said, ‘We’re not going to remove him, you should have organised your event better!’”

In the meantime, preparations for the staging of the Space Ritual tour continued apace. Smith continues, “Logistics were down to me, along with keeping the happy-go-lucky bunch focused! I had the first planning meeting with Barney Bubbles at my flat in Acton. We decided he would put a schedule together, covering design and marketing, as well as organising the building and painting of the backline.”

Various ideas were mooted, including touring the show like a circus in an inflatable plastic tent. More outlandishly, it was suggested that synthesist Del Dettmar be seated on a revolving tower above the heads of the audience. Yet as the tour approached, Dave Brock told Sounds, “It’s coming along slowly, but there’s so much work. You don’t realise how much until you start. Our normal number of people on the road is 16, but with this we’ll need 24, and they’ve all got to be paid. When I see it all written down, I tend to freak out, because apart from all that, we’ve got to get it all together musically too.”

The expanded road crew that Brock refers to included a new lightshow team. Mike Hart and Alan Day of Proteus Lights – who had been working on and off with Hawkwind for the previous two years – were joined on the Space Ritual tour by Jonathan Smeeton, a veteran of hippie club Middle Earth and the Roundhouse. Smeeton brought a collection of ambitious lighting effects to the party, using multiple slide projectors to create crude but effective animated loops. Coming together as Liquid Len and the Lensmen, Smeeton, Hart and Day developed a groundbreaking spectacle that would become another defining aspect of the Space Ritual experience.

While Brock was worried about the nuts and bolts of putting the show together, Robert Calvert and Barney Bubbles were more concerned with the philosophy behind it.

Some commentators in the press had already noted that Hawkwind had developed a dedicated, even militant, fanbase who regarded the band as revolutionary heralds of an alternative lifestyle rather than just entertainment. Calvert was happy to expand on this idea to NME: “All generations have had some sort of revolutionary feeling in them, but this is the first that isn’t based on any political ideals. Consequently, it’s the job of the musician to put these feelings into music that people can recognise. Our gigs seem to get into a very ritualistic, tribal thing where people come to lose their personal identity and expand their consciousness collectively.”

Bubbles was even more committed to the mystical element of the upcoming shows, writing a ‘manual’ for the press that previewed his ideas. “The basic principle for the Space Ritual is based on the Pythagorean concept of sound,” it said. “Briefly, this conceived the universe to be an immense monochord, with its single string stretched between absolute spirit and absolute matter. Along this string were positioned the planets of our solar system. Each of these spheres as it rushed through space was believed to sound a certain tone caused by its continuous displacement of the ether. These intervals and harmonies are called ‘The Sound Of The Spheres…’”

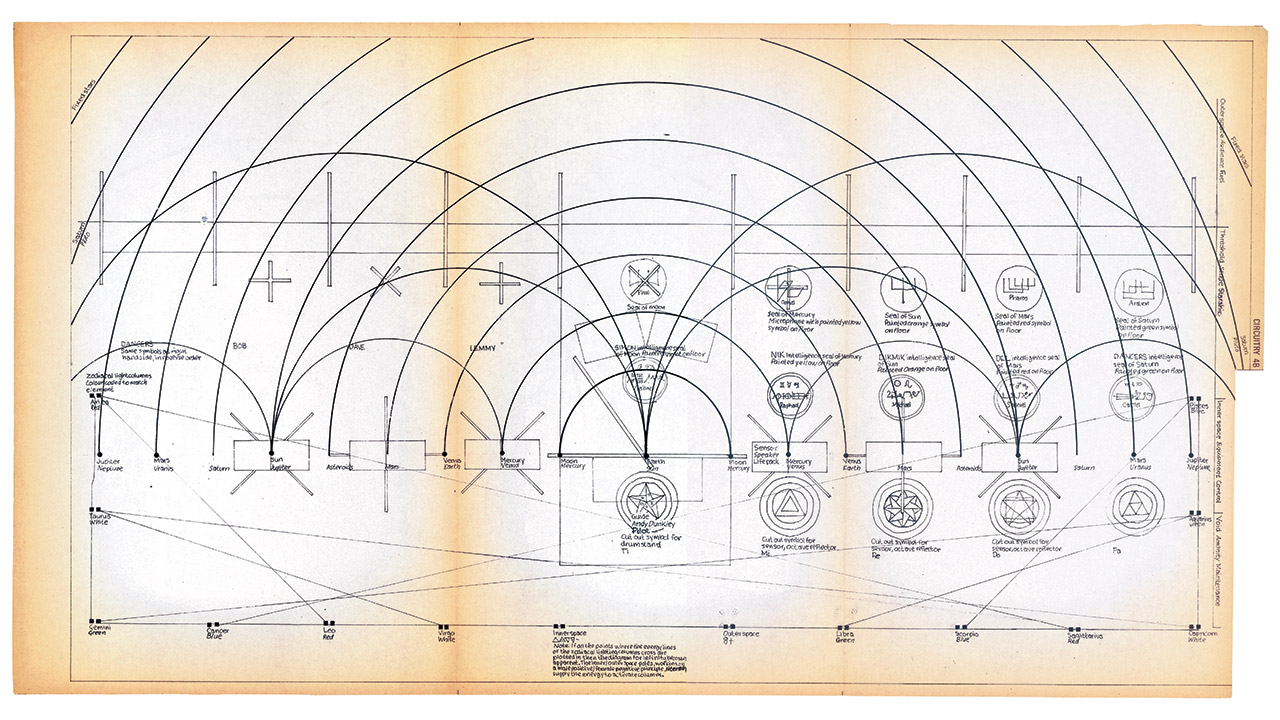

As Doug Smith recalled, “Barney sent me a neatly handwritten schedule that included a couple of plans of arched spherical curves of the music and light lines crossing. He told me that if the band got it right with the lights and music onstage, they would take off!”

Nik Turner remembered similarly: “Barney conceived the whole stage show, where he took the astrological signs of people in the band and used the corresponding colours to position them on the stage. Our equipment was set up to correspond with Barney’s plan. Nobody was going round with a tape measure saying, ‘Stand here!’ but we tried to emulate what Barney had laid out.

“Barney designed the actual equipment as well, the speakers were supposed to be on these flexible bases so they could jump up and down! Barney had a total concept, and I helped him. At the time, Robert was having a nervous breakdown and wasn’t available to make any sort of decisions. So I worked with Barney on these stage production and design ideas, and choreographing the dancers, and I was very excited to be involved.”

The dancers that Turner refers to were another key element of the Space Ritual presentation, acting as human lightning rods for the music and a point of focus for the audience. Hawkwind’s regular visual interpreter, the statuesque and often naked Stacia, was joined by the sylph-like Miss Renée, a 20-year-old American who had previously danced with the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Also present onstage for the first few gigs was John May, a writer for underground newspaper Frendz, who was subsequently replaced by mime artist Tony Crerar.

Of course, in parallel with organising the tour, there was the small matter of recording Hawkwind’s next album. Wisely, the band decided to do it at Rockfield Studios. Situated in the South Wales countryside, Rockfield was a relatively basic facility then, but had the advantage of being as far away as possible from the distractions of Ladbroke Grove. The seclusion clearly worked, with the album quickly recorded during two sessions in September ’72.

Titled Doremi Fasol Latido, a punning reference to the Pythagorean scale, the album was originally intended to act as a ‘preview’ of the Space Ritual tour, with nearly all of its songs featured in the set. However, problems at UA’s pressing plants put paid to that, and it wasn’t actually released until the tour was well underway. But given the strength of the material, this almost certainly wasn’t an issue for the majority of fans.

In Search Of Space may have pioneered Hawkwind’s propulsive, trance rock sound, but it’s positively airy compared to the pounding oblivion of DFL, like black treacle oozing from the speakers: Brainstorm is a dense, muggy blast of exhaust fumes and amphetamine acceleration; Lord Of Light is a groovy galactic chug; Time We Left This World Today is a mind-stomping call-and-response number.

The 32-date Space Ritual tour – which saw Hawkwind repeatedly criss-crossing the UK, from Aberdeen in the north to Exeter in the south – finally got underway on Wednesday November 8, 1972 in King’s Lynn.

As a band with a reputation for narcotic indulgence, the attention of the local drug squad was always a problem, as Doug Smith recalls. “I remember the King’s Lynn gig well. [Road manager] John the Bog had nicked some roller skates from a previous gig in Cambridge, and then produced them from the truck at King’s Lynn, where I joined him skating around the venue. A few minutes after, the police arrived. Everyone disappeared, leaving Del and DikMik doing their subsonic thing onstage, which sent the sniffer dog crazy! John skated up to the Inspector to introduce himself as Crew Chief and as he was speaking, dropped his stash in a bin right next to the inspector! He collected it later in the evening once the police had left.”

To build anticipation each night, every audience member received a joss stick and a free programme containing lyrics and the tongue-in-cheek Extract From The Saga Of Doremi Fasol Latido, wherein Hawkwind are depicted as spacelords returning to Earth to enforce peace. Before their entrance onstage, resident DJ Andy Dunkley would lead the audience in a countdown. But nothing could adequately prepare them for what was to come.

The band’s new backline of 2,500 watt stacks blew the PA in King’s Lynn, which meant that at subsequent dates, including the following night at Dunstable’s Civic Hall, the band were forced to use only one of the stacks. But that didn’t diminish the synapse-frazzling impact that the Space Ritual presentation had on the audience, judging by reports from this show.

With its distinctive ‘flying saucer’ roof, the Civic Hall had been the venue where the Silver Machine promo was shot, and given its relative proximity to London, the Dunstable date was chosen to be press night for representatives from all the major music papers. The frustrating paucity of live Hawkwind films taken during the 1970s means that, other than a few photographs, their reviews remain the best depiction of just how amazing the Space Ritual shows sounded and looked, and how powerfully they affected the audience.

For Martin Hayman at Sounds, both sound and vision were overwhelming: “Spidery figures wield guitars and crash drums in the flickering half-light at the end of the hall, packed with a dense mass of people, a sort of freaks’ convention… The throbbing bass hits the base of the spine like a subliminal battering ram, the high frequencies from the synthesiser and the sax attack the front of the head, the flashing lights that frame one second the ancient mysterious shrine of Stonehenge, the next the Hawkwind insignia, disintegrate into sharp geometrical edges and shadows.”

For John Pidgeon at NME, “The audience reacted physically to each mood created onstage, [and] became part of the spectacle. Whenever the stage gave off electronic pulsations, the crowd became uneasy, restless, perturbed; when the characteristic heavy metal riffs started up, the sense of relief was physically manifest, the audience on their feet with tendril arms swaying above their heads. The lights were directed behind the band onto a screen where a montage of meteorological, astronomical, sonic and electronic images flashed, and in front onto the three dancers…

“The effect on the band, obscured between this sandwich of light, was to eliminate individuality in the same way as their music does. Solos do not remain in the mind, instead a combined force of the incredible.”

Martin Marriott at Disc contrasted Hawkwind’s performance with standard rock gigs: “Here was a band which had created a unique situation. No cries of, ‘Rock’n’roll’, no billiard cues flailing, just good feelings and peace signs… From the first twitterings and rumblings of the set, every person there was totally involved in the Ritual… By the end, 2,000 people were up on their feet, arms over heads, clapping. To say that the audience left satisfied would be this year’s understatement.”

It was a sentiment echoed by Record Mirror: “The group’s performance was nothing short of sensational… [When] the band left the stage, five minutes of solid stamping continued until Hawkwind returned and smashed the collective skull with a riotous version of Silver Machine merging into You Shouldn’t Do That, its insistent beat and breathless chant whipping 2,000 spaced-out lunatics into a final ecstasy of whirling and shouting.”

Despite being 50 years ago now, the memories of many fans who attended the Space Ritual shows remain vivid. “I was fortunate to see the Space Ritual at Middlesbrough Town Hall,” recalls Grahame Lake. “This certainly wasn’t a bunch of acid-head hippies playing drippy post-60s rock. It was an aural and visual assault that left you blown away. The vacant looks on everyone’s faces as they left highlighted how exhausting and brutal these concerts were.” Pete Zabulis saw them in Derby: “I’d never seen anything like it before!” and Ian Whittaker speaks for many when he says, “The Blackburn gig set me off on a lifelong journey.” Meanwhile, Adam Jones, who saw them in Newcastle, comments on the legendary volume of these shows: “My ears have only just recovered – it certainly cleared the fog on the Tyne!”

Traversing the country inevitably led to occasional logistics issues. As John May recalls, “The tour bus broke down on the way from Leeds to Bristol, and we had to hire three taxis from Birmingham, travelling in a high-speed convoy to the Bristol gig, and arriving late, with the audience in a frenzy. The front of the stage was so low that people were mobbing us!”

But tragedy struck after the Norwich gig, when the van containing John the Bog – real name John Burroughs – was involved in a collision on the outskirts of London. He was flung from the vehicle and died immediately.

It was always the plan that the Space Ritual show would be recorded for future release, with the performances at Liverpool Stadium and London’s Brixton Sundown – the tour’s final show on December 30 – used for the eventual album. (The Sunderland Locarno show was also recorded, but there was a problem with the tape.) Doug Smith has bittersweet memories of Brixton: “At the end of the show, Nik went onstage and thanked everybody, what a great tour, and then he comes off stage and passes me and says, ‘Oh shit, I forgot you!’ I was a bit miffed – fucking hell, I’d put it all together!”

Insult to injury then ensued. “We were all going to meet up somewhere to have an end-of-tour party. Marianne and Lisa, two girls who were staying with me at the time, had booked a late night bar and were going to call me when they got there to give me the address. So Dave and I went back to my place in Acton to dump everything, planning to get a cab back to wherever the party was. But there was no call… We sat there until four in the morning smoking joints and becoming very pissed off. Then Marianne and Lisa walked in: ‘Great party!’”

With Silver Machine playing over the end credits of the Christmas Day edition of Top Of The Pops, 1972 had been an astonishing year for Hawkwind, seeing the band emerge from the underground to become one of the hottest names on the British music scene. And 1973 would be another big year for them. In February, they played a gig at Wandsworth Prison in London, Smith having somehow convinced the Home Office that a sustained blast of anti-establishment space rock was what the inmates needed to aid their rehabilitation. In March, they became one of the few major bands at the time to play Belfast in Northern Ireland.

In May, the rest of the world got to hear what the Space Ritual shows had sounded like with the release of Space Ritual, the album. Coming in another eye-popping, Barney Bubbles-designed sleeve, it remains the only Hawkwind album to break into the UK Top 10, peaking at No.9 in the charts.

From the eerie electronics of Earth Calling through to the warp speed crescendo of Master Of The Universe, Space Ritual is like no other live record released at the time or since. Its dense, gravity-sucking sound is as black as the cosmic void itself, the immersive intensity of the experience grabbing hold of the listener and refusing to let go. Born To Go’s brutal, cyclical riff pummels the air, a thrilling exercise in velocity and propulsion; Orgone Accumulator is a hip-swivelling, foot-stomping slab of space-age biker boogie; Brainstorm is Hawkwind ram-raiding the doors of perception, the paranoia police in hot pursuit.

One of the unique features of the show was the spoken-word pieces delivered by Robert Calvert with icy precision, a chance for both band and audience to catch their breath, and a coolly enigmatic presence at the heart of Space Ritual’s fearsome engine. The most renowned piece is Sonic Attack, which was issued as a one-sided promo single ahead of the album.

“Sonic Attack was a government health warning concocted by Michael Moorcock,” explained Nik Turner. “It was the dark side of what was going on. The government were issuing all these warnings which were completely stupid: you know, in the event of a nuclear attack, get under the table and paint your windows white. It was crazy. If that’s what they think people will believe, they obviously don’t have a very high opinion of people!”

On May 27, Hawkwind promoted Space Ritual’s release with a major gig at Wembley Empire Pool (now OVO Arena), their biggest headline show in the UK. Doug Smith says: “I was sitting behind these big WEM speakers we’d hired from Pink Floyd. We’d invited the head of the American label over to see the show, and there was this look on his face of, ‘Fucking hell!’ We’d been dubbed the poor man’s rock’n’roll band, but Wembley just proved a point…”

The Space Ritual would be the basis of Hawkwind’s live show until the end of the year, when the band toured the US for the first time, selling out the 6,000-seater Chicago Auditorium before they’d even got on the plane.

It was the concept that took the band to a new level of adulation among fans while heightening their notoriety among the more conservative members of the press. It was a special moment in rock history that showed it was possible to do something radically different with the live format – and an unforgettable experience for everyone who was there.

This article is dedicated to Nik Turner (1940-2022). Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from Nik are from an interview conducted with the writer in 2017.

This article originally appeared in issue 136 of Prog Magazine.

Joe is a regular contributor to Prog. He also writes for Electronic Sound, The Quietus, and Shindig!, specialising in leftfield psych/prog/rock, retro futurism, and the underground sounds of the 1970s. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, MOJO, and Rock & Folk. Joe is the author of the acclaimed Hawkwind biographyDays Of The Underground (2020). He’s on Twitter and Facebook, and his website is https://www.daysoftheunderground.com/.