"If we’d kept things together and stopped arguing, we could have all been multi-millionaires!" The story of Hawkwind's most prog-friendly album, Warrior On The Edge Of Time

Bruised and battle-weary after a punishing live schedule, in 1975 Hawkwind weren’t in the best place ahead of recording their fifth studio LP. But what emerged was a stunning tour de force of science fantasy-inspired progressive space rock

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

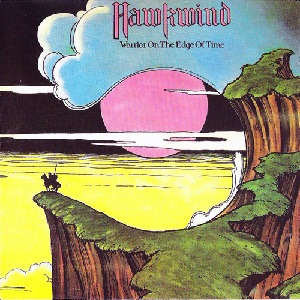

Hawkwind's fifth studio album, 1975's Warrior On The Edge Of Time, might easily be their most prog-friendly, but its genesis was far from easy with the band seemingly at each other's throats the entire time. Still, from chaos came greatness as Dave Brock and others told Prog for this 2025 cover story...

“It’s getting to be like a war, isn’t it?” – Dave Brock, December 1974.

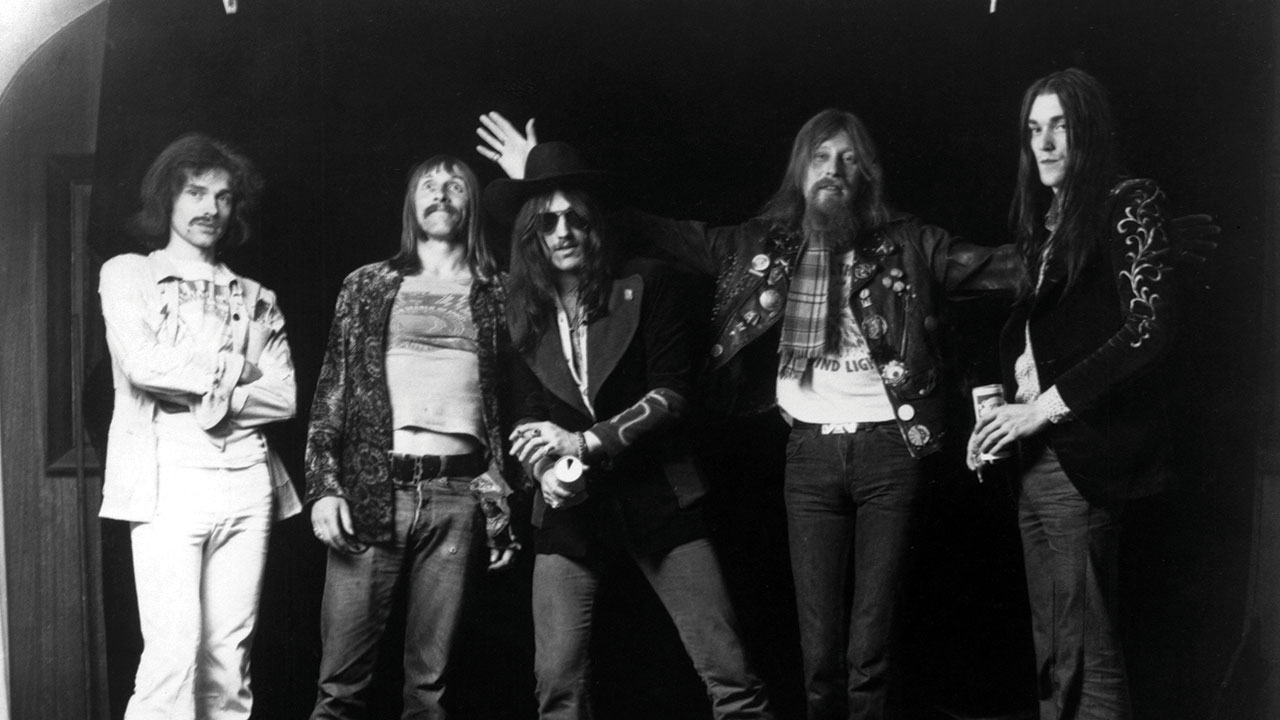

At the beginning of 1975, Hawkwind were at the peak of their commercial success. The band were in the middle of their annual UK winter tour – extended over three months – and were playing to thousands of adoring fans each night in sold-out city halls up and down the country. They’d also started to break North America, having toured there twice the previous year, with their last album Hall Of The Mountain Grill making a decent showing on the Billboard chart. They were a band in demand, and apparently destined for even greater things.

But they were also physically and mentally exhausted, and fast approaching burnout. As the quote above (taken from a Melody Maker interview with Allan Jones in February 1975) highlights, bandleader Dave Brock felt they were in the middle of a ceaseless military campaign. Hawkwind had a reputation as a hard-gigging band, with their early success built on bringing the good news of the counterculture to every town in Britain, creating a dedicated following in the process. Yet despite working as much as possible outside of the mainstream music industry, they increasingly found themselves on a corporate treadmill, spending months away from home on the road and operating more and more like a traditional rock group.

In fact, ever since their 1972 single Silver Machine had become an unexpected smash hit around the world, Brock and saxophonist frontman Nik Turner in particular had become concerned about losing touch with Hawkwind’s roots as a ‘people’s band’. The money generated by the single had enabled them to mount the Space Ritual Tour, which had acted as a springboard for their current trajectory as a major cult band breaking into the big time. But it meant the days of Hawkwind being able to play a benefit gig for free at the drop of a hat were long over.

Looking back today, Brock remembers it as a stressful time: “When you’re doing one album after another, and it’s successful, the record company want you to knock another one out as soon as possible. There was a lot of pressure all the time. It did us in. We did one tour of North America, had two weeks in England, then back to America again. All of us in the band had problems, not being home that much. And everybody had American girlfriends, it was all very complicated…”

Things came to a head in the latter stages of the UK tour in February 1975. Hawkwind had already played three concerts in London that month, but they’d booked an additional show on the 16th at the Roundhouse, originally intended as a benefit for the charity Radical Alternatives To Prisons. However, following the theft of both Simon King and Alan Powell’s drum kits from the band’s west London lock-up, the show had turned into a means of buying new equipment (despite both kits being recovered before the gig happened). Speaking to International Times, Turner expressed his displeasure at the change: “I’m told that our financial situation is what governs that sort of decision and that’s what pisses me off, having to come to terms with the fact that it is a business… That is the sort of situation I very often find myself in, torn between what I really believe in and the reality of the situation.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The reality of the situation at the Roundhouse was heavier than just

a clash over where the money was going – with the gig sold out once again, around a thousand people had been locked out of the venue, some of whom decided it’d be a good idea to try and burn down the side entrances. Not for the first time at a Hawkwind gig, the police had to attend to restore order. For the band, it was the final straw, with the rest of the tour cancelled to allow them some time to properly recuperate.

There was also the small matter of making their next album. In the UK and Europe, Hawkwind were in a state of record label limbo, the band’s contract with United Artists having ended after the recording of the Kings Of Speed single in January. Released in March, hopes had initially been high for it, with Simon King commenting at the time, “It’s the same as Silver Machine. Well, near enough, anyway.” But it failed to repeat the success of the original, with John Peel commenting in his review for Sounds, “Hawkwind exist in some curious time-warp in which no account is taken of what may be happening elsewhere.”

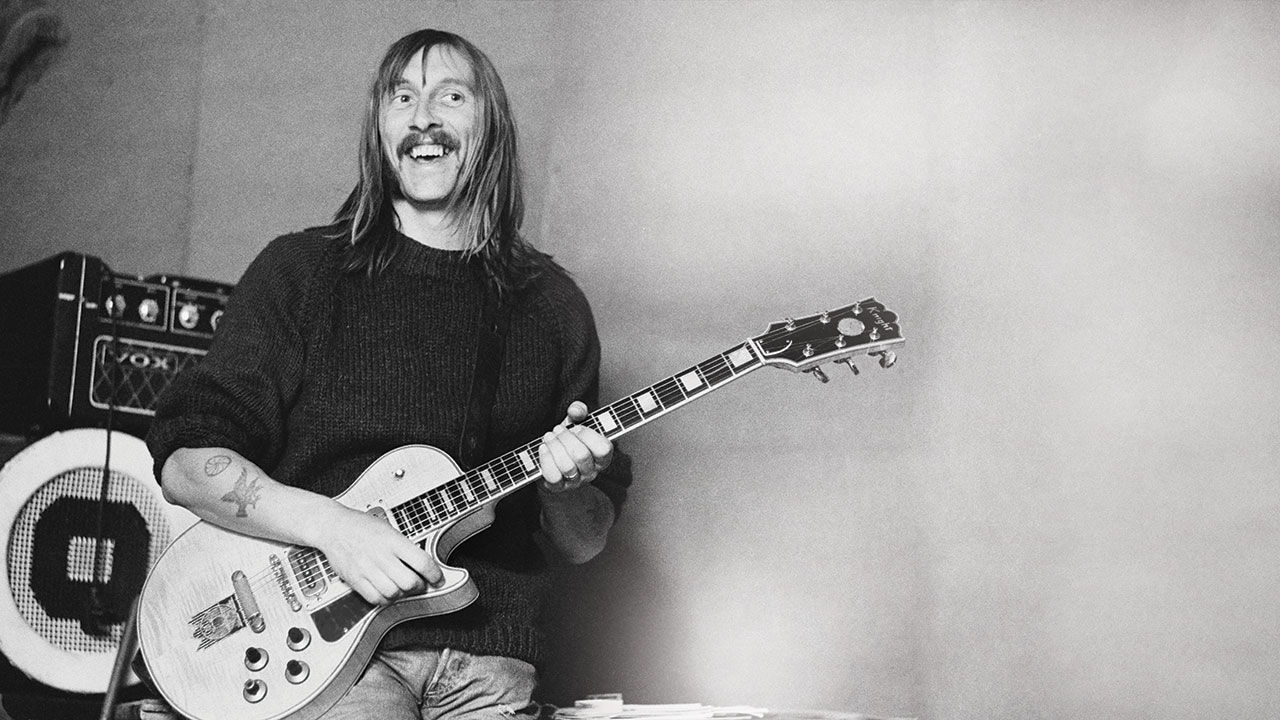

While this was the prevailing view among many in the press, it wasn’t entirely accurate. Kings Of Speed would end up on the album to come, but its stoned cosmic boogie wasn’t representative of the much more progressive direction the band were travelling in. Key to this new sound was keyboardist and violinist Simon House, a classically trained musician who had previously been in the brutally psychedelic High Tide and the avant-medieval Third Ear Band. Drafted in as a replacement for Hawkwind’s legendary electronics duo of DikMik and Del Dettmar, House’s Mellotron and synth work had significantly augmented the band’s sonic palette on Hall Of The Mountain Grill, and his playing on the next album would dramatically build on this foundation.

Alan Powell also played an important role. Hawkwind’s newest member, he’d joined the previous summer as a temporary replacement for an injured Simon King, and then remained in the line-up after King had recovered. Thus was born “the Drum Empire”, as bassist Lemmy would witheringly refer to the band’s double drummer configuration. Yet this wasn’t just an exercise in brute force. As well as being a seasoned session player, Powell was a skilled percussionist and budding songwriter, and would make a telling contribution on his first album with the band.

With the United Artists contract at an end, manager Doug Smith had wasted no time in securing a new US deal for the band with Atco, an imprint of Atlantic Records. But in combination with another American tour lined up for May, this added further pressure to the band’s schedule, with Atco stipulating that a new album had to be out to coincide with the tour.

It was fortunate, then, that Brock and the band had already started putting new material together, based around a rough concept suggested to them by leading fantasy author and regular collaborator Michael Moorcock. In fact, there had been talk for a while of mounting a full-scale theatrical rock show based around his Eternal Champion books, with Arthur Brown earmarked for a lead role. In the end, this didn’t come to fruition, but a couple of Moorcock’s spoken-word pieces – Standing At The Edge and Warriors – that had already been in the band’s live set for some time would appear on the new album. And the title that Moorcock gave them – Warrior On The Edge Of Time – positioned Hawkwind away from their science-fiction roots, aligning them instead with the burgeoning ‘sword & sorcery’ genre.

However, the band that entered Rockfield Studios in March 1975 were still suffering from the after effects of their relentless live work, and interpersonally wasn’t in the best place, to say the least.

Brock remembers, “We were doing very well, but there was friction within the band, and a lot of weird things going on at that time. We had two drummers, which Lemmy hated. And there were problems with Turner squawking on his saxophone…”

Brock had talked at length about this friction in his interview with Allan Jones in February ’75. Like the rest of the band, he was losing patience with Lemmy.

“At Hammersmith, Lemmy’s lead kept coming out of the amp, and he carried on playing. He’s so deaf he didn’t even realise. That’s what annoys Simon House, Lemmy plays so loud he can’t hear a thing we’re playing. And we’re all shouting to Lemmy, ‘Your fucking lead, man!’ and he still didn’t understand. Then somebody plugged it in and I told him, ‘If you do that again, I’ll fucking kill you.’ And sure enough he did it again. We were all freaking out about that.”

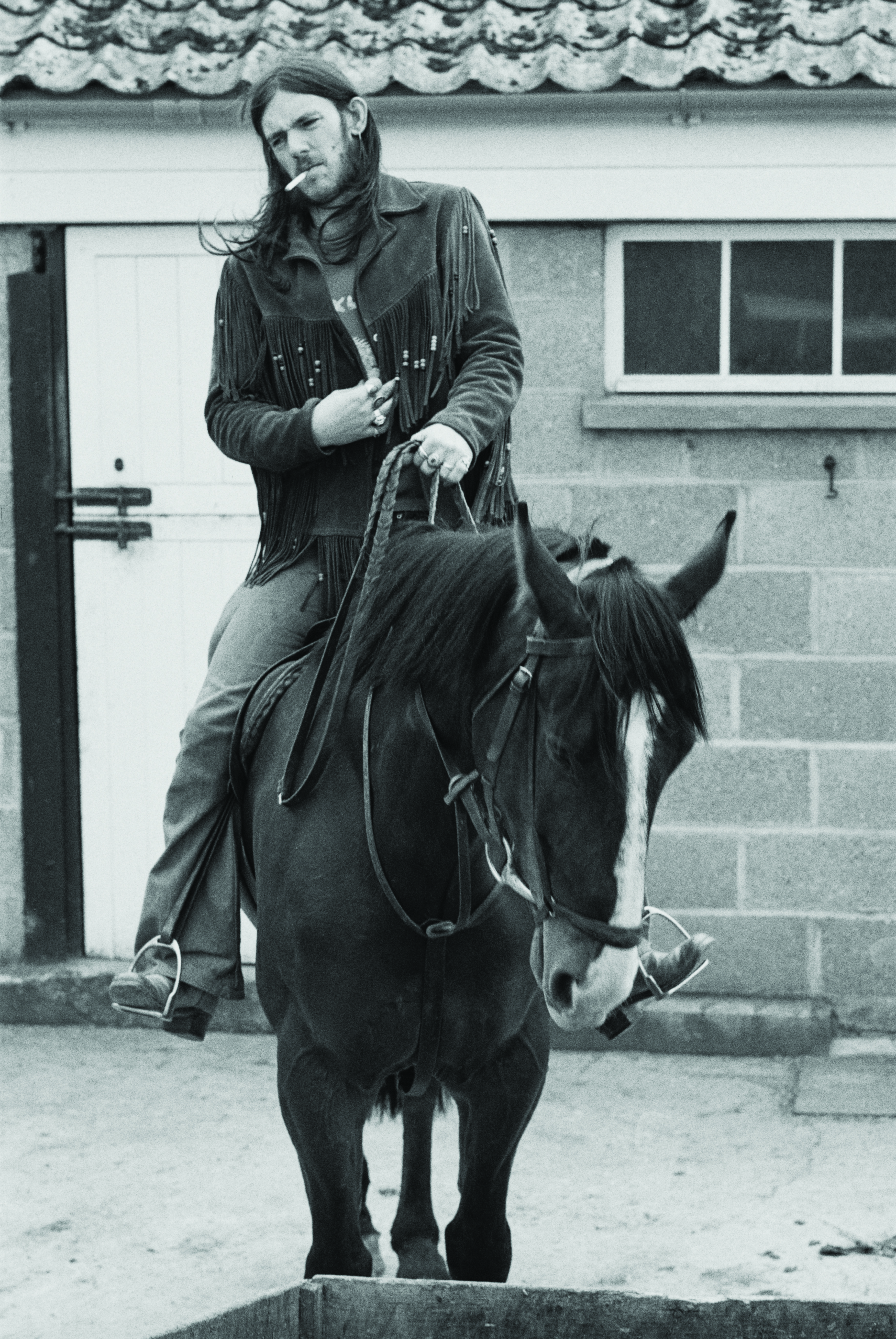

Lemmy’s amphetamine habit was identified as being at the root of the problem, with the band often at loggerheads with their speed-wired bassist. As Turner told Carol Clerk in The Saga Of Hawkwind, “Everybody had agreed that it was increasingly difficult to work with him because of the drug situation, and because he always had to be right.”

Turner expanded on this latter point in The Spirit Of Hawkwind, the book he wrote with Dave Thompson: “Lemmy would come up with these hare-brained schemes and then get upset and angry when the rest of the band said, ‘Well, no.’”

In his autobiography White Line Fever, Lemmy conceded, “I was just too forward for the rest of the guys.”

But his own personal ire was reserved for the Drum Empire: “Simon and Alan’s two drum kits were set at the centre of the stage in this huge semi-circle of percussive effects. It jolly well made sure that you knew your place! I’ve seen a lot of pompous drummers in my lifetime, but this pair were ridiculous. As far as I’m concerned, this was the end of Hawkwind because those two killed it between them.”

And while Turner was wrestling with his conscience as the band became more of a business than a community project, his lack of discipline as a live musician was irking Brock, as he recounted to Jones: “Some nights I’ve unplugged my guitar and marched across the stage to sort Nik out. He keeps playing the saxophone when I’m singing and I’ve told him a thousand times not to do that.”

Overall, the picture he painted was far from pretty.

“You wouldn’t believe some of the scenes that go on backstage. All the fucking rows, people losing their temper when things go wrong or somebody’s not doing it right.”

Given the general level of unhappiness within the band, it would have come as no surprise if the Rockfield sessions had quickly descended into a mass brawl. But what the angry quotes above don’t capture is the fact that, despite the simmering resentments, all those months on the road had turned Hawkwind into an incredibly powerful musical entity with an intuitive sense of interplay between members. And despite the pressure they were under, Hawkwind went into Rockfield and, in just three and a half days, recorded the backing tracks for what many consider to be their finest studio album. They then returned to London, and spent another three days in Olympic Studios overdubbing and mixing the songs. Warrior On The Edge Of Time, a classic of progressive space rock, had taken less than a week to make.

The album begins with the two-fisted punch of Assault And Battery

and The Golden Void, segued to create a seamless, and mind-bendingly trippy, 10-minute track. Sonically, it’s one of Hawkwind’s most ambitious pieces of music, thanks largely to the free rein given to Simon House to embellish and illuminate it wherever possible. His blazing Mellotron, in tandem with Lemmy’s irresistibly propulsive bass line, immediately conjures visions of Moorcock’s fantastical worlds, Assault And Battery surging forward like an eldritch army about to engage in battle.

Brock is also in commanding voice, his opening lines, ‘Lives of great men all remind us/We may make our lives sublime’ taken from A Psalm Of Life by 19th-century American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Speaking to Malcolm Dome for the sleeve notes of WOTEOT’s 2013 reissue, Brock said, “I used to read a lot of poetry in the 1960s, and that’s probably where I came across it. But the notion of a rock musician taking a quote from a great poem wasn’t anything new. Bob Dylan had done it for years, and let’s face it, everyone is always borrowing from various sources.”

The Golden Void is even more dramatic, its brooding opening

section moving into an intense bolero-style summoning of the old gods, House’s synths weaving an incredible basket of light as Brock delivers another committed vocal. And if Turner wasn’t always the most reliable player live, his sax solo at the end of this song is just glorious, and arguably his finest performance on a Hawkwind record. Even Lemmy, who perhaps understandably didn’t have much time for WOTEOT, called it “a beautiful track”.

Next up is the first of the album’s three spoken-word pieces, The Wizard Blew His Horn, recited by Moorcock himself. Some critics have characterised these tracks as a misstep, and Moorcock has described his performance as: “Hasty. I was in a hurry to go and see a movie and did all the numbers too quickly. I didn’t like The Wizard… much and would rather have done something a little less ‘fantasy’, but Dave liked it.”

Yet these atmospheric interludes add to the album’s uncanny charge, the eerie backings created by Powell, King and House verging on the avant-garde.

The instrumental Opa-Loka begins with waves before locking into a mono-chordal hypnotic groove that strongly recalls the krautrock minimalism of Neu! (Brock wrote the sleeve notes for the UK release of their debut album). A Powell composition, he describes it as “a studio jam I’d made a demo of in my flat. Lemmy was unavailable, so Dave Brock played the bass on it. It’s basically trance rock… In the early 90s, when raves were the big thing in America and everybody was taking ecstasy, Opa-Loka was apparently played a lot.”

Fittingly, its title comes from Opa-Locka, a town in Florida with Arabic architecture inspired by One Thousand And One Nights.

Despite its stark title, The Demented Man is one of Brock’s loveliest acoustic-based songs, with a weathered warmth to both his finger-picking and voice. It’s a sympathetic and affecting portrayal of someone losing touch with sanity, although Brock suggests it can be interpreted in a number of ways:.

“It could be a lunatic asylum – ‘White walls stretching in the sun…’ Or

it could be about being born, a baby’s first experience of coming from the womb into a hospital. It’s up to the individual to work it out.”

Kicking off side two in a Hammer horror-style squall of wind and rain, Magnu features one of Brock’s most memorable stun guitar riffs, and another formidable sound clash between his roiling wah-wah, Turner’s bubbling sax and House’s banshee violin. This time, Brock borrows lines from The Invisible Knight by Polish writer Aleksander Chodz´ko and Hymn Of Apollo by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

“That was a major inspiration for the song. Shelley had taken the idea from ancient legends, so I was claiming it back,” he told Malcolm Dome.

The second spoken piece is the chilling Standing At The Edge, with Turner voicing the anger of a damned immortal army, ‘Veterans of a thousand psychic wars’. This is followed by House’s joyous Spiral Galaxy 28948, a glittering synth-drenched instrumental in jazzy 6/8 time, and further proof of Hawkwind’s desire to expand the boundaries of their music.

“Simon is a very clever musician,” Brock said to Dome. “This track is typical of the sort of thing he’d come up with, but it tends to confuse the rest of us poor chaps!”

The title is a not-quite-accurate reference to House’s date of birth: August 29, 1948.

Warriors is the final spoken track, delivered by Moorcock through a Dalek-style ring modulator, its words paraphrased from his 1970 novel, The Eternal Champion. It leads into Turner’s songwriting contribution to the album, Dying Seas, Lemmy’s querulous bass line underpinning a quirky but appealing song with a mysterious syntax-mangling lyric. With the band unable to recreate the vibe of the original demo at Rockfield, they decided to include it as was, though in Brock’s opinion, “I don’t think that detracts at all from the quality.”

The album was rounded off with the inclusion of Kings Of Speed. Often assumed to have been tacked onto the end at Atco’s request, Brock had already suggested to Allan Jones that it was in fact part of the WOTEOT concept. Closer inspection of the Moorcock-penned lyric bears this out with its references to the world of Jerry Cornelius, the writer’s anarchic, androgynous character who offered a modern spin on the eternal champion trope.

Not only did WOTEOT feature a strong and varied selection of material, it also sounded distinctly fantastical, the mix a thing of shape-shifting magic, somehow both murky yet startlingly present.

Brock told Dome, “I sat up all night sometimes working on the album… someone had to take responsibility for the way it was sounding, and it usually ended up being just me.”

However, not everyone was impressed, Alan Powell in particular: “The sound and production was at best amateurish – it sounds like it was recorded on a Sony cassette player. But Dave wanted it ragged and messy, it’s just the way he liked to hear it.”

Warrior On The Edge Of Time was released on May 9, 1975, just eight months after Hall Of The Mountain Grill. With contractual negotiations still ongoing, United Artists had to license it from Atco in order to release it in the UK and Europe – ongoing licensing issues were the reason why the album would be officially unavailable during the 90s and 00s, only rectified in 2013 with a box set reissue from Atomhenge that included a Steven Wilson remix.

Reaching No.13 in the UK charts, it would be Hawkwind’s highest-placed studio album, and also their last to make the US Billboard chart, at No.150. It was a bitter irony, then, that the American tour they had rushed to complete the album for finally led to a decisive break in their ranks.

Crossing the border into Canada on May 11 for a show in Toronto, Lemmy was arrested for the possession of a suspicious white powder. Released the following day when it turned out, of course, to be amphetamine sulphate rather than cocaine, Lemmy made it to the show. But it had proved to be one headache too many for the rest of the band, and in a meeting afterwards, their talismanic bassist was fired. This would be just the first of a series of ructions that would knock the band off course for the next few years – and for many fans, it’s the point at which ‘classic’ Hawkwind ends.

Warrior On The Edge Of Time remains Hawkwind’s most prog-friendly album, but as with all their output, it’s uniquely their own take on the idea, assimilating the sonic adventurism of the progressive bands into their dark rhythmic churn. And in Assault And Battery, The Golden Void and Magnu, it gave the band three of their most loved and long-standing live tracks. As Brock said to Dome, “It is a genuine Hawkwind classic – there’s some really great stuff on it.”

It’s possible that the friction within the band was at least partly responsible for the album’s strident, often fierce sound – as Hawkwind fan John Lydon would point out a decade later, ‘Anger is an energy.’ But as Brock ruefully concludes, “Probably if we’d persevered and kept things together and stopped arguing, we could have all been multi-millionaires – but we didn’t!”

Joe is a regular contributor to Prog. He also writes for Electronic Sound, The Quietus, and Shindig!, specialising in leftfield psych/prog/rock, retro futurism, and the underground sounds of the 1970s. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, MOJO, and Rock & Folk. Joe is the author of the acclaimed Hawkwind biographyDays Of The Underground (2020). He’s on Twitter and Facebook, and his website is https://www.daysoftheunderground.com/.