Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Nik Turner is a man for whom the phrase “force of nature” could have been invented. He might now be in his late 70s, but he shows no sign of slowing down any time soon. Prog catches up with him as he travels to the Space Mountain festival in Granada, Spain, before then flying to the US to begin a tour in support of his latest album, Life In Space.

It’s clear that he still lives for the opportunity to play music to a crowd, with a question about Erich von Däniken leading to a lengthy anecdote about falling in with a troupe of Chick Corea-loving jazz musicians in Mexico City, and finding himself playing romantic Latin music in a transvestite strip joint.

It’s also clear that he’s a man who both lives in and for the moment – when asked about his new album, he admits that he was happily surprised to discover he had one coming out, and says, “I haven’t heard it since we recorded it – I’m very intrigued by it!”

Turner has collaborated with numerous bands, both live and on record, over the past 40 years, but it’s still the time he spent as Hawkwind’s sax and flute player, and de facto frontman, during the group’s classic early-70s period that still defines him in most people’s eyes.

While the progressive bands of the time were creating rock that aspired to the complexity and virtuosity of classical and jazz music, Hawkwind were travelling in the opposite direction, playing a new type of deep space psychedelia that valued rhythmic intensity and miasmic noise over technical perfection. Turner was central to both, conjuring and channelling the sonic chaos of the Hawkwind sound, his squalling, free-form sax often indistinguishable from the band’s barrage of electronics.

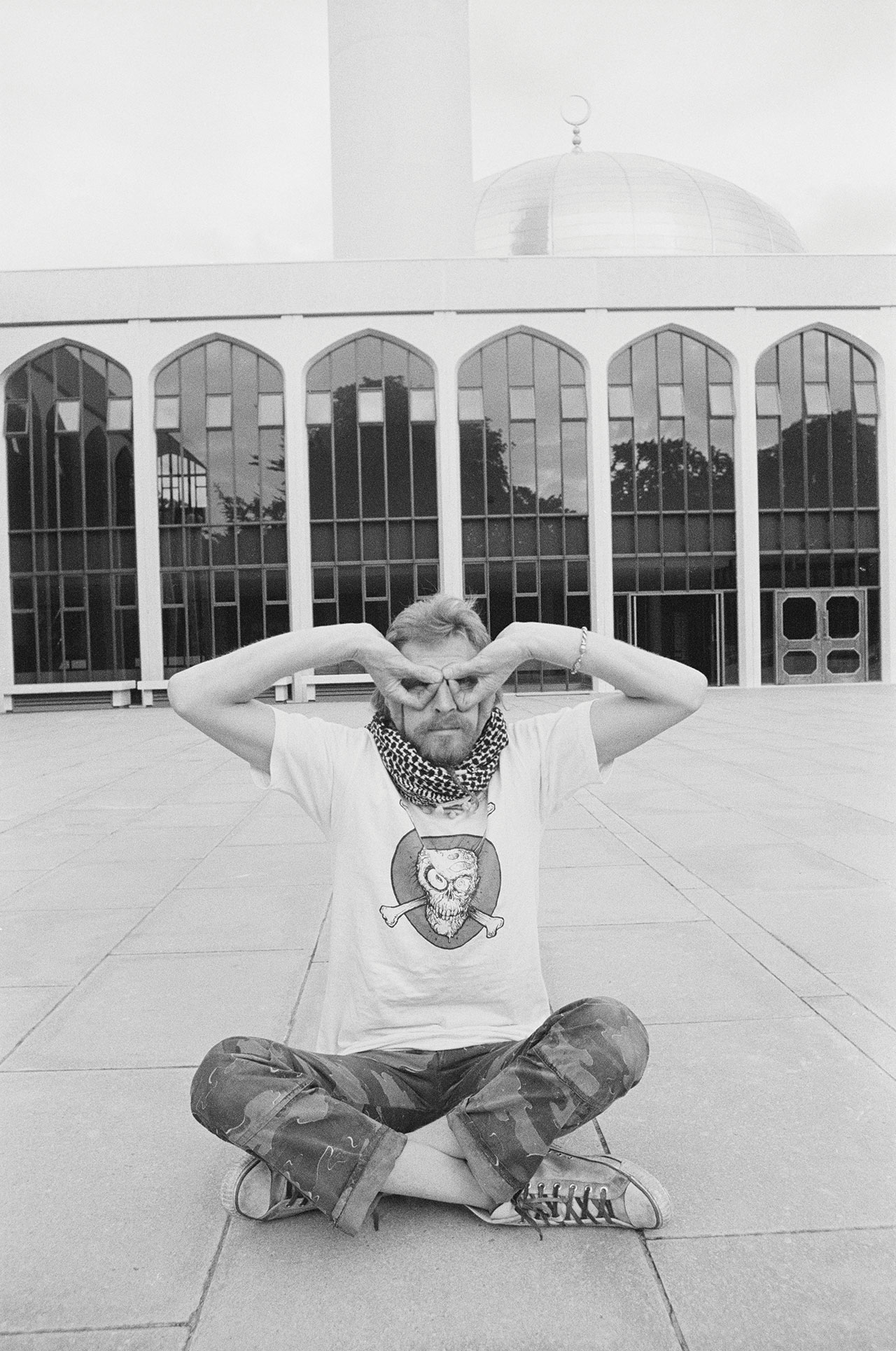

With flame-red hair and beard, and standing at well over six feet tall, he transformed into the Mighty Thunder Rider on stage, a persona midway between master of the universe and cosmic clown prince.

While Life In Space contains plenty of the driving, mind‑expanding music he’s best known for, it also finds Turner in a more reflective mood on tracks such as End Of The World and Back To Earth. The album also features guest spots from ex-Hawks Paul Rudolph and Simon House. “I never fell out with anybody really,” he says. “I’ve always remained friends with people. The only person I haven’t remained friends with is Dave Brock…”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Despite his key role in the original band, Turner has become a deeply controversial figure for many Hawkwind fans over the past few years, with band founder Brock launching legal action against Turner to prevent him from using the Hawkwind name in the US. The case recently concluded, with the judgement going in Brock’s favour.

From his early years as a teenage jazz fan in 1950s Margate right up to the present day, Turner’s story is full of incident and colour. As Prog soon discovers, he’d already experienced a lifetime’s worth of adventures even before joining Hawkwind in 1969…

Does music run in your family?

Yes, my mother played the piano. She was a fan of Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, Oscar Peterson. The piano was always being played, and I wish I’d learnt it – she was always trying to encourage me. But I eventually learnt to play the clarinet. I was then really inspired by Charlie Parker, so I got a saxophone. I was particularly excited by Earl Bostic – he had an alto sax and had a hit record called Flamingo and I just thought, “Wow, that’s the sound I want!”

Did you have formal training?

Yes, I learnt to play a scale and to read music. A guy up the street from me was a bandmaster for the marines band – he played in local dance bands, and he got all the local boys to play. There was a whole cult of players who were playing modern jazz at that time – MJQ, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane – and I just lapped it all up. I used to watch these bands regularly, then I would go and play on the beach and serenade the seagulls!

Growing up in a seaside town at the time could be interesting…

I worked on Margate seafront selling funny hats and postcards for a time, and the mods were all friends of mine, but I was friends with the rockers too. The mods would throw a dustbin through the window of a chemist’s shop and come out with bags of they didn’t know what, and they’d give it to me to look after. And I’d look after the motorcycles for the rockers. I was sort of in both camps, really.

After a stint in the Merchant Navy and further travelling, you eventually ended up in Berlin in the late 60s…

Yes, I spent Christmas at the parents of a German guy I knew. His family had a jewellery factory, and so we hired a space in this big hall selling joss sticks, hippie stuff, and jewellery as well. At night I used to go out on my own, cruising around the psychedelic clubs. I was quickly accepted by the people there, and I used to hang out with Edgar Froese.

I got adopted by all these arty German musicians, who would take me around all the local venues. The Pretty Things were playing at one place doing S.F. Sorrow, and Amon Düül were playing in a commune, which is where I first encountered [future Hawkwind bassist] Dave Anderson.

How did your time in Berlin change your attitude to music?

I was also hanging out with all these free jazz musicians at the Blue Note club. They were banging away on a piano with hammers, feeding back on a double bass with a microphone on it; very experimental. And they said, “You don’t need to be technical to express yourself,” and I thought, “Oh, great!” Free jazz in a rock band – that’s what Hawkwind were to me eventually.

How did you meet Dave Brock?

I was working in Holland, banging stakes into the ground as a roustabout in a rock’n’roll circus. In Amsterdam, one of the bands that turned up were the Famous Cure, which was Dave Brock and Mick Slattery. When I went back to England, I kept in touch with them. I used to stay with Dave, slept on the floor in his cold water flat in Putney. We used to have a great time. Then they said they were getting a band together, and I was going to be their road manager!

Because you had a van?

Yes, a Thames van, nothing fancy, but useful for ferrying equipment around. I went to one of their rehearsals and mentioned the fact that I had my saxophone with me, and they said, “Oh, bring it in.” I played it and they said, “Great! Do you want to join the band?”

You’ve referred to Hawkwind as first and foremost a community project. Did you set out to create a different kind of band?

Not really, but I tried to encourage freedom – free thinking in the music and a democratic attitude. Everybody in the band was from different backgrounds. Dave Brock and Mick Slattery were blues players, while our bass player, John Harrison, used to be with the Joe Loss Orchestra. And we had a drummer [Terry Ollis] whose family were scrap metal dealers – he’d had one lesson from Phil Seamen. Then there was DikMik, who I’d known in Margate.

You also knew Robert Calvert from there?

Yes, we hung out a lot together. We’d go out and get drunk and take a load of drugs: speed, LSD, magic mushrooms. Unfortunately, he was manic depressive – his mother, who was a state-registered nurse, told me that he had breakdowns every 18 months on a regular basis.

How did your role in the band evolve over time?

I became frontman by default. I said, “I’ve written this song called Master Of The Universe – who’s going to sing it?” and they said, “You’re going to sing it!” I’d never sung or aspired to be a singer, and suddenly I found myself in a recording studio in front of a microphone. Suddenly I was the frontman in the band.

What are you most proud of from those early years playing with Hawkwind?

The spontaneity of it, doing free gigs and community benefits, playing on the back of a lorry, playing in prisons, going to Aldermaston on CND rallies, and just being community-spirited. I really liked the whole London underground scene – Hoppy [John Hopkins], Jeff Dexter, Mick Farren. I used to sell International Times on Margate seafront! A lot of the dealers were friends of mine, and they gave me bottles of liquid acid. I ended up with a refrigerator of the stuff, so I took it to the gigs and gave it away to the audience! It sort of created Hawkwind’s reputation, the alternative attitude. People still come up to me and say, “You changed my life,” and I say, “Well, I hope I didn’t do you any damage!”

Hawkwind were a unique band in the early 70s – nobody else was really doing what you were doing…

I’d say so. I went to college in Canterbury and I knew The Wilde Flowers, who became the Soft Machine, along with East Of Eden and Caravan, but none of them were really doing anything like what we were doing.

You’ve talked about using your sax as an “electronic medium” rather than a conventional instrument. What effects did you use to achieve that?

Everything! I had a wah-wah pedal, I had a doppler, phasing, echo, anything I could get my hands on. People from the Arts Lab were making stuff and used to give it to me – they gave DikMik his first audio generator too. For instance, the siren sound at the start of Master Of The Universe is actually me. I listened to Stockhausen, John Coltrane and John Cage. With Hawkwind, I was trying to embody all of that, but I was also learning to play properly.

Can you describe what having a hit with Silver Machine meant?

I just thought it was fantastic. I never imagined we’d become successful like this. But then money suddenly crept into the picture, which was sad because that wasn’t really what it was about to me. I organised a gig in Bayswater and got introduced to Larry Parnes. He said, “I’d really like to manage your band!” I said no thanks, but I actually rather regret that now!

Did you see Hawkwind fitting in with the contemporary progressive scene at all?

Not really, I thought we were more avant-garde. A lot of those musicians had classical training, but they lacked soul, I think. I preferred Arthur Brown and Edgar Broughton, those sort of bands.

Did you follow what people like David Jackson and Mel Collins were doing in terms of integrating sax with rock?

Yes. Dave Jackson used to come and have a blast with us when I had my band Inner City Unit. But I was very much more self‑taught.

There was some controversy when you first left Hawkwind, a feeling that the band weren’t going in the right direction. Did you see it this way?

I just got bored with it really – all the back-stabbing and control-freakery. I was quite relieved to leave. And then going to Egypt and recording flute music inside the Great Pyramid was just this thing I did on the spur of the moment.

What was that like?

It was awe-inspiring. I went inside the Great Pyramid, clapped my hands and whistled, and realised what a great sound it had. I thought, “Wow, I must record this just for myself.” But when I got back to Britain, I was still under contract to Charisma Records, so I chatted Tony Stratton-Smith up…

I’d been adopted by these Bedouins in Egypt and they lent me a horse to go riding in the desert. They invited me to this engagement party where they had all these fabulous Arab horses dancing on their hind legs, even when somebody fired a shotgun in front of them! I took a load of photographs and showed them to Tony, who was a horse owner, which really inspired him.

Gail Colson, who was his right-hand person, thought we should go into a studio with Steve Hillage and put an album together [Xitintoday by Nik Turner’s Sphynx], based on the Egyptian Book Of The Dead.

How did Inner City Unit form?

I was working with Barney [Bubbles] at the time and he was a big inspiration. I also wanted to do something a bit more exciting. Barney was working for Stiff Records at the time, and Nick Lowe, who had his own studio, gave him some recording time. Barney asked me if I wanted to do a single, but we did an album instead, which was Passout.

Was punk an influence on ICU?

I used to hang out with Malcolm McLaren and he introduced me to the Sex Pistols. They’d just played the Marquee with Eddie & The Hot Rods, and they bragged about how they’d smashed all of Eddie’s equipment up. And I thought, “Oh, that’s what punk’s about then…” A bit sad really. I was more into music than punk, which was one‑dimensional. I didn’t want to be limited by just one chord!

How did you come to rejoin Hawkwind in 1982?

ICU had got into hard drugs and I couldn’t really deal with that, so I broke the band up. I’d been made an offer by Dave Brock to go on the road again with Hawkwind and I was happy to accept. I started improvising all these weird costumes, wearing a luminous body stocking based on blood corpuscles, an idea from Barney, and then this strange kind of space clown outfit, and I did gigs on roller skates with a wireless microphone.

Later on, I had flashing lights in my saxophone and I was carried on stage in a coffin. I had my head shaved with just a spike of luminous pink hair on top. It was quite bizarre.

After leaving Hawkwind again, you formed Nik Turner’s Fantastic Allstars, and then Space Ritual, a band that included ex-members of Hawkwind. Was this born out of a desire to reconnect with the ethos of the original band?

Yes, that’s what I was trying to do, to embody the original Hawkwind spirit.

But you started to run into various problems over the use of the Hawkwind name…

I just like to play music – I’m not interested in the men in suits. They have their place, but I’m not a great fan of theirs. There’s all this fractious, bullshit legal stuff going on that I’m not really into. I got coerced into being involved. I try to distance myself from it.

Do you regret getting involved in the legal action over the band name?

Yes, I do. I feel that it shouldn’t have been necessary, and I find it rather embarrassing. My label in America, Cleopatra, got a bit bullshit music businessy, and I’m not really into that sort of thing.

Do you feel you’ve been misrepresented in this process?

Yes, I do. It’s just not me. I’m now in the process of trying to extricate myself from that situation and get back to reality. It’s all so divisive. I would be quite happy to go out in America as myself, as Nik Turner, not as Hawkwind or any other facet of Hawkwind. Just Nik Turner and his music – that’s how I’d like to be seen.

If you could say something to those Hawkwind fans who blame you for this situation, what would it be?

That I feel I still embody the spirit of what Hawkwind was originally about. I like to play good music, and play with heart and soul.

You’ve gone through a bit of a renaissance in terms of your recorded output in the last few years, with Space Fusion Odyssey featuring guest spots from Billy Cobham and Robby Krieger…

Brian Perera [head of Cleopatra] said, “You should make a jazz fusion album,” and I said, “Yes!”

I was amazed how well received it was. I mean, wow, me and Billy Cobham! It’s also got the guitarist from Megadeth on it [Chris Poland], and John Weinzierl [Amon Düül II]. It was fantastic, though I didn’t physically play with them – I did most of the recording in Wales. But that’s the direction I want to go in really.

You’re setting off on tour again soon. Where does the urge to keep performing come from?

I’m an exhibitionist and I like music! I want to play awesome and exciting music. It’s not my ego, really. I don’t think I have one, though some people might beg to differ!

Finally, how would you like to be remembered?

I’d like to be remembered fondly and kindly and positively. As somebody who was innovative. And modest! And that I’ve done something by using music to heal people…

I did a gig in Brighton where they were showing the Do Not Panic film, and during the Q&A, I said that when I came back from Egypt, having spent so much time inside the Great Pyramid, I found I had this healing power in my hands. I never made anything of it, I just tried to heal people if I could. And a woman in the audience said, “I’ve got this terrible pain in my shoulder, do you think you can heal it?” “Well, I can try!”

I put my hands on her and thought about what I call my Egyptian mumbo jumbo, transmitting positive sunshine energy into people and breathing out all the negative energy. And the woman said, “Oh, the pain’s gone!” I don’t go round saying I can do this thing, but I think I can.

Life In Space is available now via Cleopatra. See www.nikturner.com for more information.

Joe is a regular contributor to Prog. He also writes for Electronic Sound, The Quietus, and Shindig!, specialising in leftfield psych/prog/rock, retro futurism, and the underground sounds of the 1970s. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, MOJO, and Rock & Folk. Joe is the author of the acclaimed Hawkwind biographyDays Of The Underground (2020). He’s on Twitter and Facebook, and his website is https://www.daysoftheunderground.com/.