“You can see we were stoned. Dave and I were completely out of our brains”: The epic story of Pink Floyd’s Live At Pompeii, the prog classic recorded next door to a volcano

Lights! Camera! Chaos! How Pink Floyd made their 1972 album Live At Pompeii

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Picture the scene. It’s the early 1990s or thereabouts, and indie rockers Radiohead are gathered at their shared dwelling in East Oxford. One night, guitarist Jonny Greenwood steps over the usual detritus of communal living – unwashed crockery, cassette cases, dog-eared music papers – shoves a tape into the VHS player and demands his bandmates pay attention.

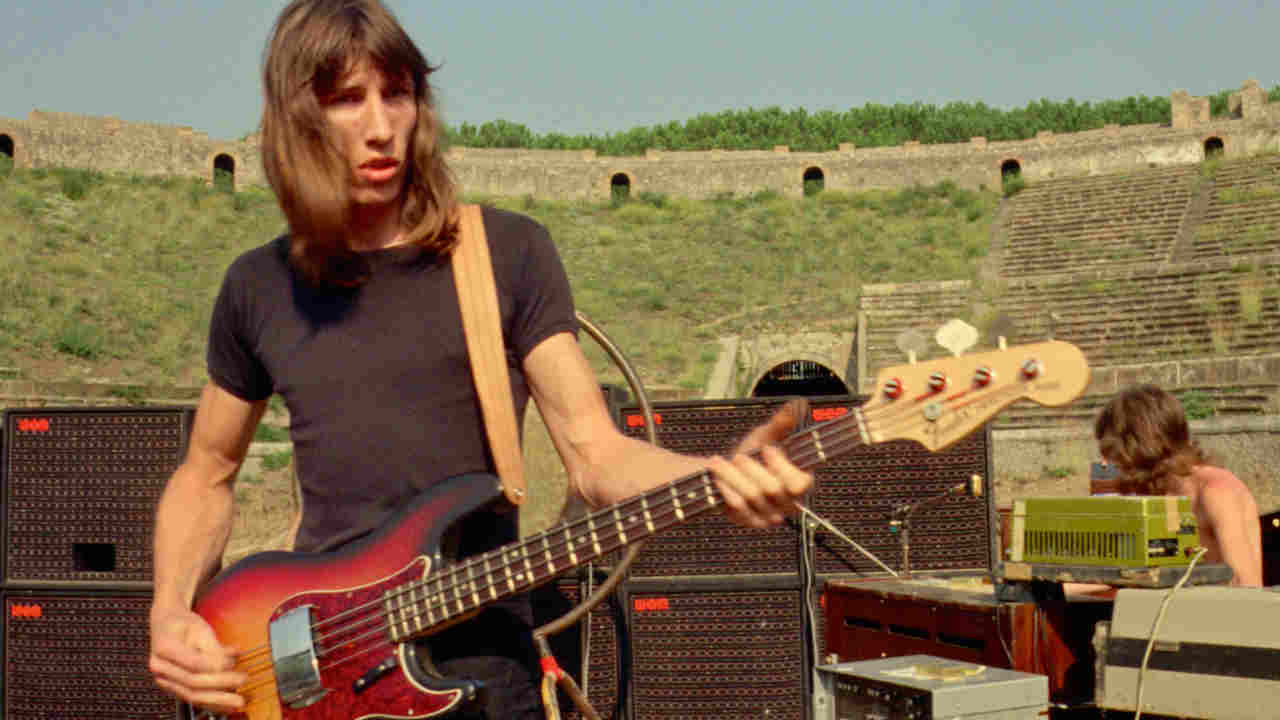

“Jonny made us all watch Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii, and said: ‘Now this is how we should do videos,’” recalled his elder brother, Radiohead’s bassist Colin Greenwood. “I remember seeing Dave Gilmour sitting on his arse playing guitar, and Roger Waters with long greasy hair and dusty flares…”

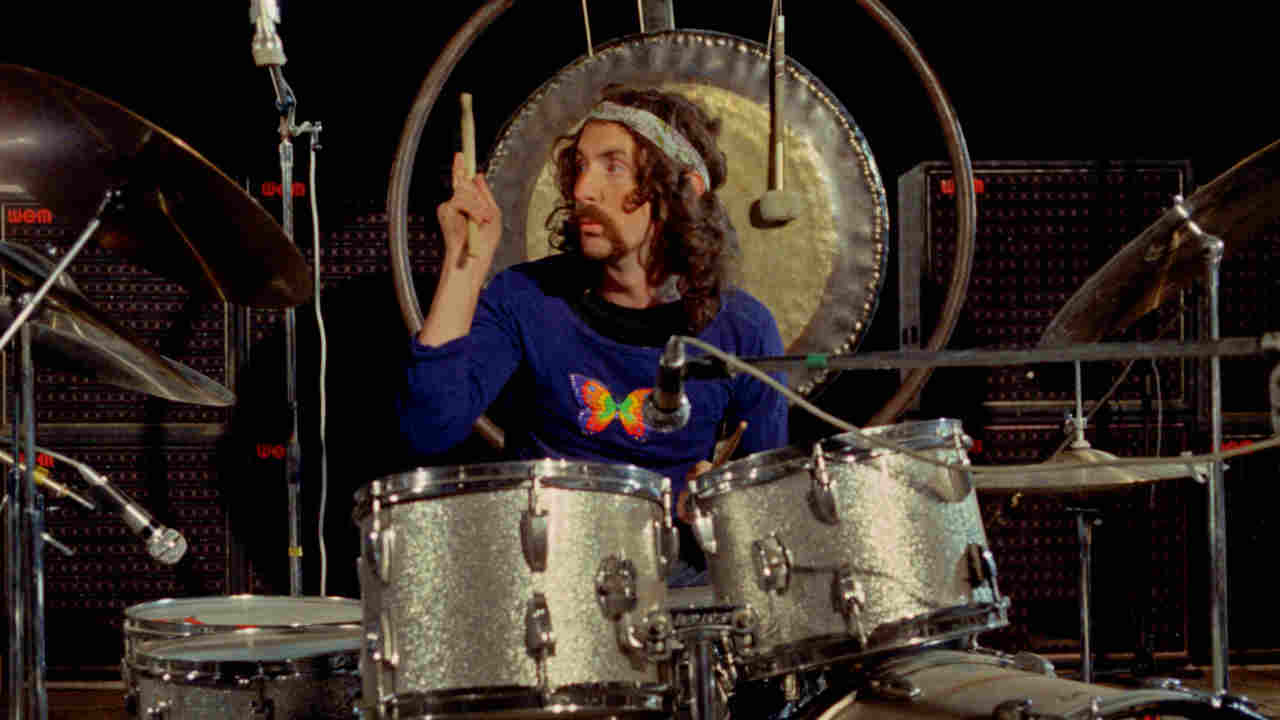

As Classic Rock recounts the tale of Radiohead’s viewing session to Pink Floyd co-founder drummer Nick Mason, he interjects. “Ah, I know what this is leading up to,” he says with a grin. “It’s about me dropping the stick.”

Radiohead’s abiding memory of the film is actually seeing bassist Roger Waters hitting Mason’s gong.

Now picture a different scene. In Pompeii’s ancient amphitheatre, Pink Floyd are performing the title song to their 1968 album A Saucerful Of Secrets, when Waters picks up what Colin Greenwood called “his big beater” and starts whacking the gong next to Mason’s drum kit. The look of maniacal purpose on Waters’s face suggests the headmaster in Pink Floyd’s The Wall dispensing whacks of the cane to a hapless pupil.

How many gongs did the band get through in their lifetime?

“Oh, only two or three,” Mason replies, authoritatively. “Gongs are almost indestructible. We had one which we set on fire with lighter fluid, gas, everything, and it still survived.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In 2017, one of the gongs was an exhibit at London’s V&A Museum, and looked robust despite being torched nightly during The Wall shows almost 40 years earlier.

So what about the dropped stick, then?

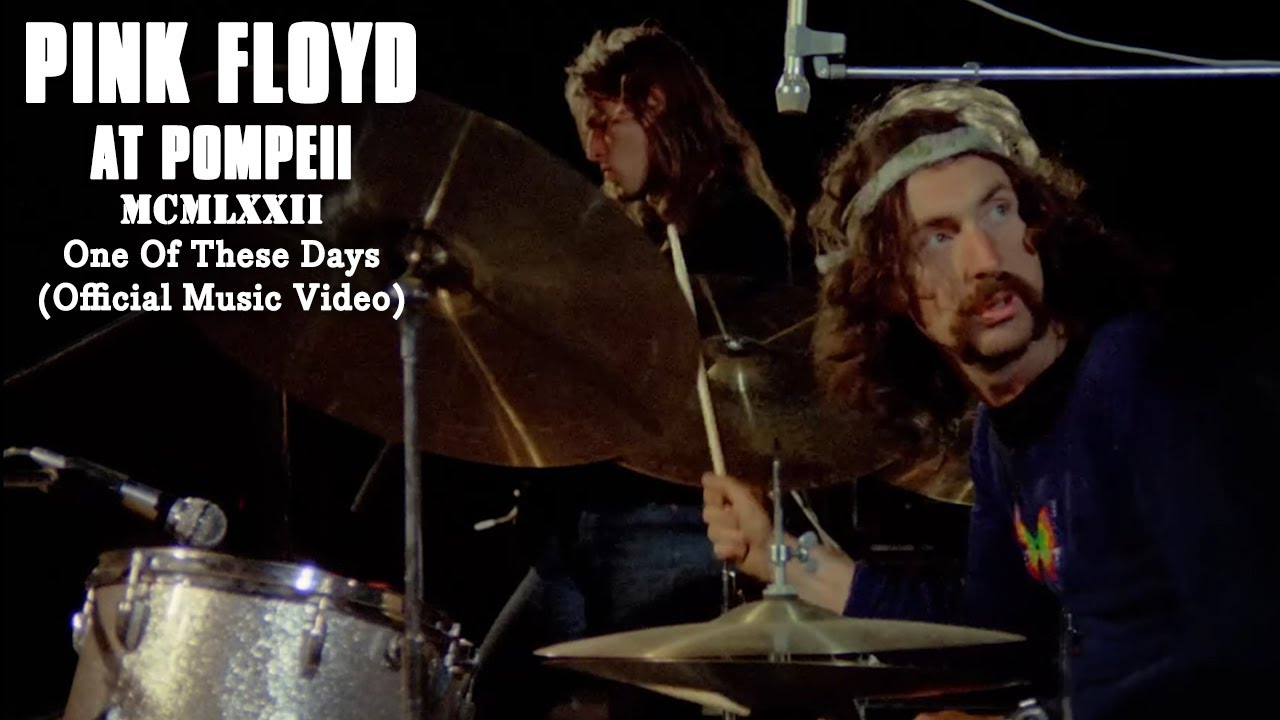

“Every drummer has seen that bit,” Mason says, referring to the moment during One Of These Days where he drops his stick, but grabs the spare so quickly he doesn’t miss a beat. “Though the general rule was always: if you do make a mistake, turn to the bass player and shake your head,” he adds.

Radiohead and the rest of the world can experience all this and much more in the newly restored film Pink Floyd At Pompeii MCMLXXII, with an accompanying live album, available as a 5.1 and Dolby Atmos mix by musician, songwriter and prog-rock remixer du jour Steven Wilson.

In 1972, Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii offered a rare document of the group emerging from that late-60s era of cult film soundtracks and performance art into the next phase, defined by the following year’s global hit The Dark Side Of The Moon. Scenes of the group making that record at Abbey Road studios were later added to the film, when no one would have had any inkling that the album would go on to sell some 50 million copies.

Pink Floyd At Pompeii MCMLXXII is, like the titular city, steeped in history, then. “But,” says Mason, sounding a note of caution. “None of us had a clue we would still be talking about it all these years later.”

Pink Floyd visited Pompeii in October 1971. It had been almost four years since their mercurial frontman Syd Barrett’s departure, and longer still since their last Top 20 hit, See Emily Play. “So we’d become an albums band because the great British public were so disinterested in buying our singles,” Mason admits.

The rejection forced them to explore other mediums. The band followed A Saucerful Of Secrets (their first LP recorded with Barrett’s replacement, David Gilmour) with 1969’s well-received soundtrack for filmmaker Barbet Schroeder’s art-house film More.

Meanwhile, their performances at London’s Royal Festival Hall and Royal Albert Hall featured BBC Radiophonic Workshop-style sound effects, and an interlude where roadies brewed mugs of tea while the members of Pink Floyd constructed a table on stage. Mason: “One of us held a leg, and another banged a nail in.”

“Some might say it was experimental, but, looking back it was pretty embarrassing,” said Roger Waters. “To be honest, we probably did all this improvisation because we hadn’t yet come up with constructive songs to perform.”

Pink Floyd explored a similar fusion of music and sound effects on their records. One of them, 1970’s Atom Heart Mother, included the track Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast, an instrumental punctuated by the sound of their road manager Alan Styles pouring milk over cereal, frying bacon and murmuring in his East Anglian burr: “Marmalade, I like marmalade…”

“It was great fun and interesting, but I don’t think we were being great artists,” Mason suggests. “Some of it was absolute nonsense. But I think we were still looking for a direction.”

By spring 1971, they’d started to find one. Making Meddle, their sixth studio LP, began with the group piecing together random sounds and scraps of music, catalogued ‘Nothing 1’ up to ‘Nothing 36’. Among the ‘Nothing’s was a piano note fed through a Leslie rotating-speaker cabinet, that sounded like the ping of a submarine’s sonar. This brainwave became the start of an epic composition, with the working titles The Son Of Nothing and The Return Of The Son Of Nothing, before becoming Echoes, the first song heard in Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii.

“As far as I recall, performing in Pompeii was the film director Adrian Maben’s idea,” says Mason. “It was down to Adrian and our manager, Steve O’Rourke. We were wise long after the event.”

Maben was a 27-year-old, UK-born Paris resident who’d studied film in Rome and made music programmes for Belgian TV. Not that Pompeii was his first choice. Earlier that year, he’d approached Steve O’Rourke about a film that paired Pink Floyd’s music with images by artists from the European Nouveaux Réalistes movement. “Tinguely, Arman and Cesar,” Maben said in 2012. “Artists who used ordinary objects to make their paintings or collages.”

Maben thought that the “strange sounds, whispers, Moogs and fuzz boxes” heard on Pink Floyd’s records leant themselves to such a visual treatment. His idea wasn’t that off-the-wall for the time. Pink Floyd had recently been in discussions with the choreographer Roland Petit to soundtrack a ballet based on the works of early-20th-century French novelist Marcel Proust. “The French had a slightly more emotional, more intellectual edge to the arts,” Mason said at the time.

Maben travelled to London, where O’Rourke and Gilmour listened to his pitch. “Then Gilmour replied, ever so politely: ‘Well thank you. We’ll think about it and ring you back. Au revoir,’” recalled Maben.

The call never came. So Maben and his girlfriend took a holiday in Italy. The original city of Pompeii had been destroyed by the eruption of nearby Mount Vesuvius in 79AD, and its ruins and relics made it a popular tourist destination. The couple visited Pompeii’s amphitheatre and ate sandwiches on the same stone cavea where spectators had once watched gladiators fighting to a bloody death.

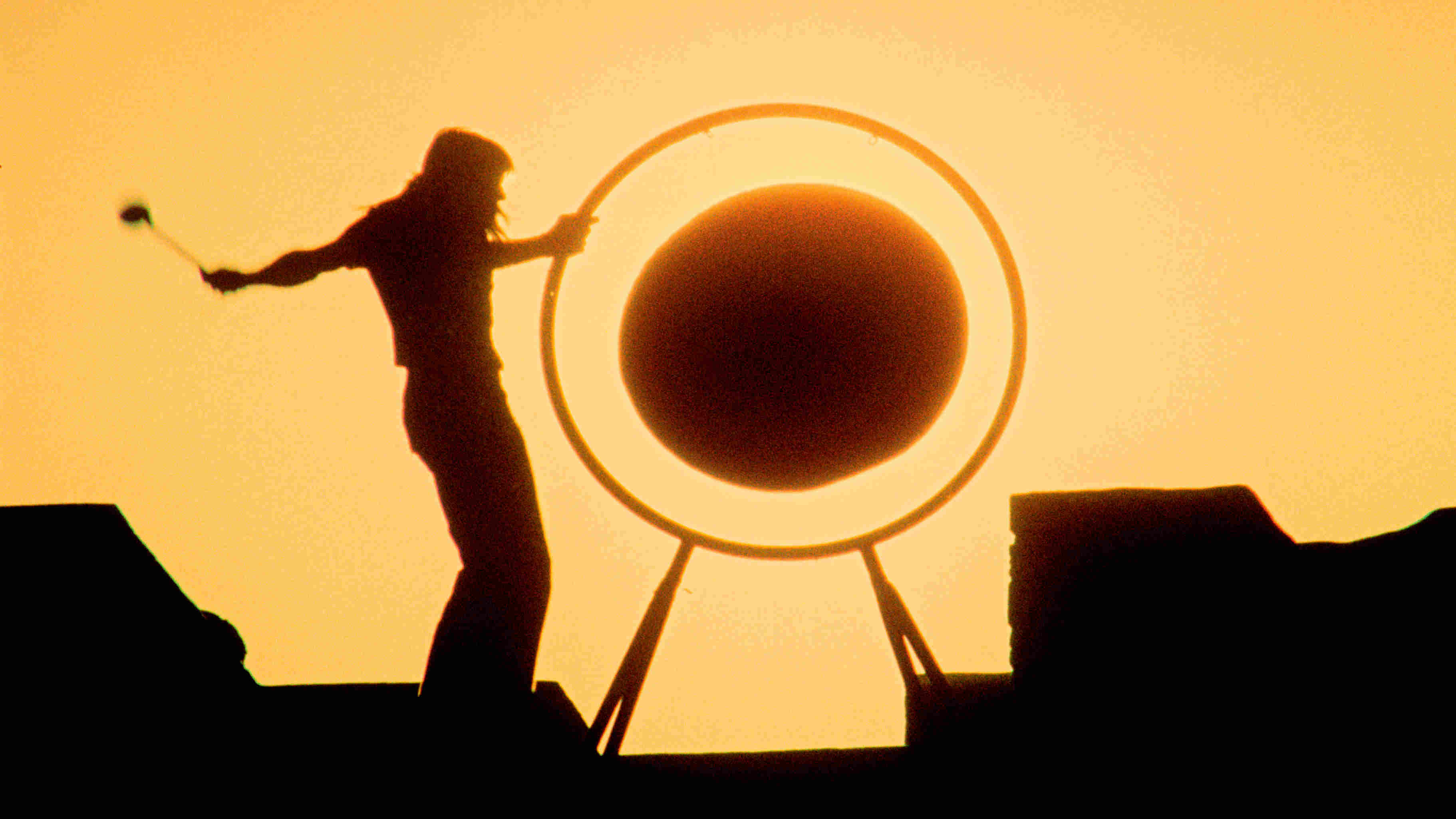

Later, Maben discovered he’d lost his passport. He traced his route back through the winding streets: past the Shrine Of The Rosary Of The Virgin Mary cathedral, to the now closed amphitheatre. It was eight o’clock at night, but he talked the security guards into letting him inside. Maben couldn’t find his passport, but he was struck by the twilight shadows, and the eerie silence broken only by the sound of insects and bats flitting between the stone walls: “I immediately knew this was the place to film Pink Floyd.”

Maben wrote to O’Rourke, explaining his vision for a “sort of anti-Woodstock”. The film of 1969’s Woodstock festival had been a box-office hit, and made a feature of the audience as well as its performers.

“I thought that was a bit of a cliché,” Maben said. “So I wanted to make a film where there would be zero audience, just the band and some of the crew, but with Pompeii itself as an integral part of the film – the amphitheatre, the streets, the ruined temples and mosaics…”

Pink Floyd signed up to the idea, and Maben enlisted a Floyd-loving local history professor to persuade the local authorities to let them use the space for a rock concert.

Once permission was granted, Maben and his executive producer, Reiner Moritz, scraped together enough funds from a French production company and various French, Belgian and German TV stations to get the project started.

Then, just days before filming, O’Rourke requested £2,000 to transport the band and its equipment to Pompeii. Maben handed over the money his late mother had left him in her will. There was no going back now.

Pink Floyd, their arsenal of keyboards, drums, guitars, amplifiers, speaker cabinets, cables, skeleton road crew (including the breakfast-loving Alan Styles) and one battered gong arrived in Pompeii on October 4, 1971.

“Maben had convinced Steve O’Rourke that playing in Pompeii was a good thing,” recalls Mason. “But we’d not given very much thought to what we were going to do or how it was all going to work. I do know we had to ditch a couple of gigs in England which had been booked – something we were loathe to do as we needed the money. They were a couple of university gigs. Probably worth about five hundred quid a night. But by the time we’d rescheduled them it was after The Dark Side Of The Moon, and our price had gone up and we were on a couple of thousand.”

The group’s nonchalant approach to the film wasn’t shared by its director. “The authorities had agreed to let us have the amphitheatre for six days,” Maben explained. “On the first day we couldn’t get the electricity to work. On day two the same thing happened again despite help from the electricity board.”

Maben realised there was only so much frisbee Pink Floyd could play while waiting around, and suggested a road trip. The band and film crew piled into a couple of vehicles and headed north to the dormant volcanic landscape of Solfatara, believed by ancient Romans to mark the entrance to the Gates Of Hell.

However, the outing coincided with the beginning of a three-day procession of the Madonna, The Blessed Virgin Of The Rosary, between the cathedral in Pompeii and the Piazza Garibaldi in Naples. Pilgrims crowded the streets, forcing the Floyd convoy to a standstill.

When they finally arrived, Maben filmed the band loping around Solfatara’s sulphurous geysers and bubbling mud pools – looking wonderfully incongruous in their Gohil boots and keyboard player Rick Wright in his hippie hat.

“There’s some rather Top Of The Pops-ish shots of us walking around the top of Vesuvius and things like that,” Roger Waters later said of the film, talking to the press in 1972. “I think Pink Floyd freaks would enjoy it.”

When the party returned to Pompeii, the Madonna had worked another miracle, and the electricity had been restored. Maben has always claimed they ran a “long cable” from the cathedral to the amphitheatre.

“But how far is it?” asks Mason.

Nine hundred metres, according to Google Maps, so it’s difficult to imagine a cable snaking that distance through the streets. But who knows?

“I thought a generator might have been easier. But it is a good story.”

After one step forward, though, Maben took another one back. The night before the first shoot, O’Rourke visited Maben’s hotel room with a test pressing of Meddle and told him that for the film, the band wanted to perform the whole of side two, the 23-minute Echoes.

“I pointed out that all my script work and timings had been for the earlier pieces, as discussed, and it would be impossible,” said Maben.

But O’Rourke wouldn’t be swayed.

The director borrowed a portable record player from the hotel concierge, and stayed up all night listening to Echoes and calculating new camera angles. The next morning, nervous and exhausted, he rallied the crew and filming finally began.

Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii is bookended by Echoes Part One and Part Two. The film’s opening shot offers an aerial view of the amphitheatre – all sun-scorched dust and stone – before closing in on the four band members at the same glacial pace as the music.

Executive producer Reiner Moritz insisted on using high-grade 35mm film, which broke the budget but guaranteed the movie’s longevity. More than half a century later, Lana Topham, Pink Floyd’s Director Of Restoration, found what she called “the elusive film rushes” in five cans languishing in the band’s archive. Each frame was then painstakingly restored by hand.

Viewing the movie today, the detail is extraordinary and the colours explosive, be they the brilliant red flashes on Mason’s drum kit, the fingerprint smudges on David Gilmour’s black Stratocaster or the patina of dust on Roger Waters’s flared trousers.

“It really was a case of ‘plug in and play’,” recalls Mason. “Adrian wanted it to feel like a live gig in a remarkable space, and not a film set – just without the attendant problems of an audience.” Floyd performed to their roadies, Maben and his crew, and some local kids who’d snuck into the arena.

David Gilmour once described Echoes as “the father and mother of The Dark Side Of The Moon”. In that sense it was music about inner rather than outer space. Waters’s lyrics explored the need for better communication (bittersweet, considering his and Gilmour’s later conflicts), and trailered the real-life issues addressed on The Dark Side Of The Moon.

The Pompeii performance of Echoes feels like the definitive version, with its additional images of bubbling lava pools and statues excavated from the volcanic ruins heightening the atmosphere.

“There’s also a magical quality to the October light in Pompeii,” Maben pointed out. “The silvery blue light of the early morning, the harsh midday sun and that coppery glow of the sun’s rays towards the end of the afternoon.”

The weather and the surroundings both contributed to A Saucerful Of Secrets, with Gilmour sat cross-legged in the baking sun, running a slide along his guitar strings, while Wright hammered the keys on his Steinway grand piano. A silhouette of Waters walloping the gong later appeared on the cover of the DVD.

Besides Mason’s dropped stick, Floyd’s nocturnal rendition of One Of These Days includes a lot of footage of the drummer, in his kung fu fighter’s headband and butterfly motif T-shirt.

Last year, Steven Wilson joined Lana Topham at a studio for a screening of the new print. “At one point, I turned to Lana and said: ‘Nick is the star of this film. Roger Waters is barely in it,’” Wilson said afterwards. “Oh, the irony.”

“The rumour is they lost a can of film from One Of These Days with David or Rick or Roger playing,” Mason explains. “So it became a triumph for me.”

It’s noticeable how free Mason’s playing is too; an homage to one of his drumming idols, Ginger Baker, perhaps.

“It’s hard to analyse how things work,” he offers. “But we didn’t have a producer [between Norman Smith executive-producing 1970’s Atom Heart Mother and Bob Ezrin co-producing 1979’s The Wall] to give us any advice beyond doing things ourselves. I think it was the same for Ringo in The Beatles. He was very rarely given any direction and would just slip into what he thought was right and usually was. But our songs changed, and it was inevitable everything would become more disciplined post-Dark Side.”

It’s also noticeable how magnificent this music sounds in the amphitheatre. Floyd’s road manager/sound engineer Pete Watts (that’s his manic laughter at the beginning of The Dark Side Of The Moon) was especially impressed. “Pete told me the sound was as good if not better than anything he’d heard in a studio,” recalled Maben. “It was because of the reverberations from the stone walls.”

“We had an eight-track machine there and it was a high-quality recording,” Mason believes. “Part of us thought: ‘Get out of Abbey Road and take all the gear down to Italy’ in future.”

“My first reaction was: ‘Oh fuck, this is going to be a challenge,’” a laughing Steven Wilson says, recalling the moment he started work on the project. “The actual performance was four mono feeds – bass, guitar, drums, keyboards, all in mono. I spent a long time restoring and cleaning it up. There have been many mixes before this, but I’ve done the best anyone could and I think it sounds beautiful.”

In October 1971, with university dates and a US tour pending, Pink Floyd swept out of Pompeii, leaving the film unfinished and Adrian Maben with an unpaid hotel bill. “Oh dear,” says Mason, “that sounds like us.”

“I was politely but firmly requested to remain in the hotel while I waited for the money to arrive from the producers,” recalled Maben.

However, the band agreed to play extra shows in November and December, to correct errors and film performances of some more songs. Careful With That Axe, Eugene, Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and Mademoiselle Nobs were then recorded on a sound stage in Paris, with images of Pompeii added as a backdrop.

Mademoiselle Nobs was actually the Meddle song Seamus, which originally featured Humble Pie guitarist/vocalist Steve Marriott’s pet collie howling along to a slow blues, but now with an Afghan hound called Nobs understudying. “And the hound howled in all the right places,” said Maben.

The director and a cameraman then joined the group for a Meddle overdubbing session at Studio Europa Sonor, and what Maben called “an improvised shoot”.

These spur-of-the-moment interviews, recorded while the band members guzzled bottled beer and fresh oysters, captured a verbal contest as gladiatorial as any in ancient Pompeii.

“Adrian! Adrian!” Mason implores, while the group guffaw at Maben’s questions. “This attempt to elicit conversation out of the chaps is doomed to failure.”

“They were both hilarious and totally focused on their work,” Maben said in 2012. “Sometimes they’d forget the presence of the camera, at other times they would make fun of the questions. At the time they were on top of the world.”

The original 60-minute cut of Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in September 1972. Two months later, 3,000 people arrived for a screening at London’s Rainbow Theatre, only to be sent home when the venue’s parent company, Rank Strand, realised the theatre was forbidden from competing with its cinema chain.

By then, though, Maben thought there was something missing from his film and contacted Roger Waters. Both were keen fly fishermen, and Maben joined Waters for a day’s angling. As they were packing up, Maben asked if Waters would consider doing a third shoot. “I said: ‘It’s nice to see you standing in the middle of an empty amphitheatre playing extraordinary music, but we don’t see how you create the sounds.’”

In October, Maben was summoned to Abbey Road studios, where the group were completing The Dark Side Of The Moon. He was told to bring just one cameraman, and given strict instructions not to interfere with the work the band were doing.

“The shoot at Abbey Road was also an afterthought,” says Mason, “but a good one in hindsight. We didn’t often allow other people in the studio, and when we did they usually got bored and went away very quickly.”

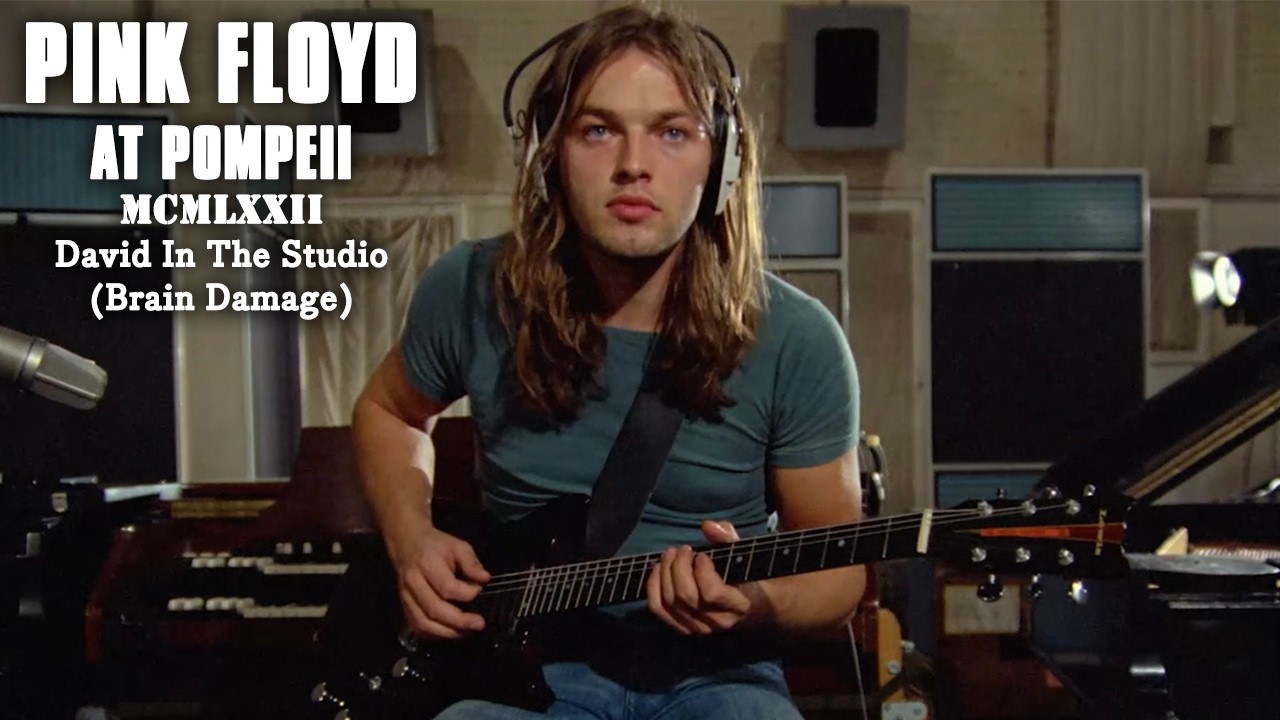

Maben and his cameraman captured the band putting the finishing touches to The Dark Side Of The Moon: Wright, wearing what looks like a Christmas jumper, playing the piano on Us And Them; Waters, burning cigarette in hand, making horror-movie noises on a synthesiser; Gilmour adding some filthy guitar to Brain Damage; and those famous scenes in the studio canteen, spotlighting the band’s dietary requirements.

“Can I have a glass of milk, please?” asks Gilmour.

“Pie without crust,” says Mason.

Maben’s separate head-shot interviews show the band members pondering the battle between art and technology.

“It’s a question of using the tools that are available when they’re available,” says Waters.

“It’s all extensions of what’s coming out of our heads,” suggests Gilmour.

“It’s like saying: ‘Give a man a Les Paul guitar and he becomes Eric Clapton.’ It’s not true,” Waters continues, with a withering grin. “Give a man an amplifier and a synthesiser… and he doesn’t become us.”

“You can see we were fucking stoned,” Waters confessed years later. “Dave and I were completely out of our brains. I was going through a stage where I was giving up nicotine, so I would roll a joint every morning.”

What does Mason think, seeing his 28-year-old self now?

“I think: ‘Oh, he’s hardly changed a bit,’” he says, laughing. “But I don’t spend my time going back to see myself demanding a piece of pie without crust or whatever. At the time, the future was a complete fog. We knew The Dark Side Of The Moon was good, but that didn’t mean it was going to be around fifty years later. Almost immediately, you’re thinking: ‘What do we do next?’”

The extended Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii was released in the US in April 1974, by which time The Dark Side Of The Moon had become Pink Floyd’s first US No.1. The cult British band making abstract noises in the Italian sunshine had become an arena-headlining act.

Since 2018, Mason has been performing with Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets, a group reprising Floyd music from the Syd Barrett and Pompeii eras. The decision to revisit Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, One Of These Days and Echoes with his own band was prompted by Their Mortal Remains: The Pink Floyd Exhibition at the V&A Museum in London.

“I liked what the V&A did but I missed the playing part,” he explains, “which is how the Saucers came into being.”

If 1967 belonged to Syd Barrett, The Dark Side Of The Moon through to 1983’s The Final Cut to Waters, and the mid-80s onwards to Gilmour, then is Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii, Nick Mason’s era?

“Well it certainly didn’t feel like it,” he chuckles. “I still don’t think of our career in eras. It’s all one era from 1967 to the present day, but not that organised, and with long periods where we didn’t have any ideas or there were disagreements.

“I’m aware that it’s a privilege to earn your living this way – doing something that’s fun. I hope maybe the Saucers do a bit more,” he adds. “But now I’m past eighty, my appetite for mid-priced hotels and tour buses has waned slightly.”

Steven Wilson first saw Pink Floyd: Live At Pompeii at a cinema in Chesham, Buckinghamshire in the early 80s.

“My dad used to play The Dark Side Of The Moon when I was about seven or eight, so I heard it a lot by proxy,” he recalls. “By 1981, 1982 I’d probably heard Animals and The Wall, but Floyd at Pompeii blew my mind. I realised this band wasn’t just about serious conceptual rock. It had that psychedelic spirit. This is probably my favourite Pink Floyd era.”

Like Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, Wilson comes from that generation of younger “Floyd freaks” for whom Pompeii is especially significant. Before the internet, it was the only visual document of a band that never appeared on TV.

Among Wilson’s favourite moments is the ambient middle section in Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun. “It’s profoundly beautiful, mysterious, enigmatic and magical,” he says, as if transported back to his teenage self sitting in that Chesham cinema.

The film’s unlikely younger advocates also include the Beastie Boys, who affectionately spoofed it in the video for 1992’s Gratitude.

However, Live At Pompeii was the last word in Floyd concert films until 1989’s Delicate Sound Of Thunder. Pompeii’s reputation has steadily grown, though.

“All credit to Adrian,” said David Gilmour, who returned to the ancient amphitheatre to record 2017’s Live At Pompeii solo album and concert film. “I don’t think any of us thought it would be as well-received and last in people’s minds for as long as it did.”

“It’s a rare document of us before Dark Side,” says Mason. “But I always wished we’d filmed us doing Dark Side and Wish You Were Here. Now you only have to turn on the television and every band you’ve ever heard of has got a live film, or else they’ve done one of those dramas with actors playing them.”

Who would play Nick Mason in a Pink Floyd biopic, then?

“Robert Redford,” he answers, quick as a flash.

And the others?

Mason laughs mischievously. “Oh, Danny De Vito for David… Bette Midler for Roger… And Richard Gere for Rick.”

Step aside, then, Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocket Man, another box office hit awaits. In the meantime, though, we’ll always have Pompeii.

Pink Floyd At Pompeii – MCMLXXII IS on general release now. The accompanying live album is out now

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.