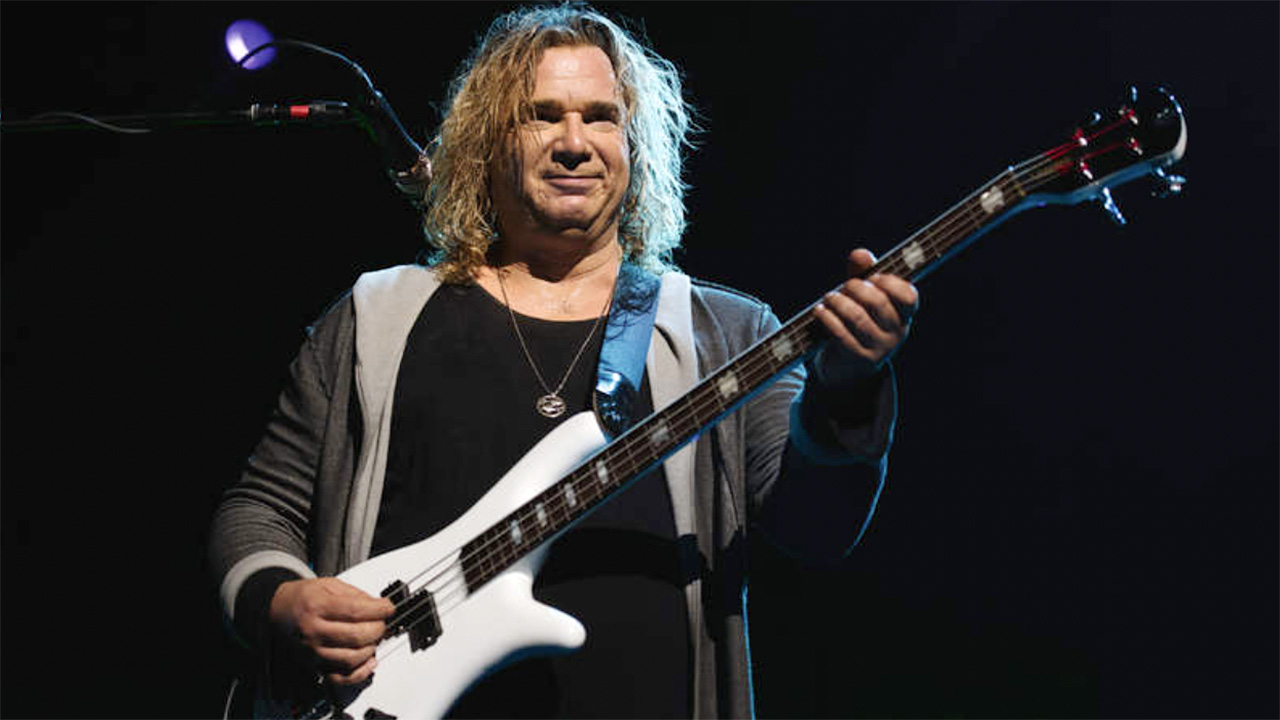

“I don’t worry about labels and I’ve ended up in the premier prog band of all time. If I’d listened to haters I’d have stopped after my first record”: Billy Sherwood’s journey to Yes started with the wayward World Trade

When Billy Sherwood reformed his 80s band World Trade for 2017 album Unify, the road to their long-awaited third release had been a rocky one. That year he told Prog how the cult band led him to full-time membership of Yes and a five-year stint with Asia, saying it had only been possible thanks to Toto and Gentle Giant.

It’s 1984, and the four members of Lodgic are rehearsing in Los Angeles, unaware that their lives are about to change forever. “Toto were in the room next door and suddenly Jeff Porcaro came running in,” Billy Sherwood recalls. “So everyone froze because, well, it was Jeff Porcaro! We feared the worst when he ran straight back out again, but he returned with David Paich and Steve Porcaro, who said they loved us.”

At a time when Toto were still among the world’s biggest bands, Paich and Steve Porcaro took Lodgic under their wings, hooking them up with A&M Records and producing an album called Nomadic Sands. But for bassist/lead vocalist Sherwood and keyboardist Guy Allison, reinvention as World Trade would be necessary for genuine fireworks to fly – and even then, genuine recognition was limited.

As we all know, Sherwood later figured in three eras of Yes’ history, where he currently remains after being hand-picked by Chris Squire to be the late bassist’s own successor, while in 1987 Patrick Moraz selected Allison as the second keyboardist in The Moody Blues.

But until Sherwood broke the news two years ago via Prog that World Trade were working on an “incredible” reunion album, the band’s name appeared doomed to remain as a pub-quiz trivia question.

The first and definitive line-up – the one that’s back together again – was completed in 1988 by guitarist Bruce Gowdy and drummer Mark T Williams. The former had been with Stone Fury, the band that gave the world Lenny Wolf of Kingdom Come fame. Meanwhile, Williams had multi-instrumental abilities and, as the son of legendary movie composer John and brother of Toto singer Joseph, he brought his own particular pedigree.

The quartet were signed to PolyGram by Gentle Giant singer-turned-label executive Derek Shulman in what Sherwood calls “a huge deal.” It was appropriate since Gentle Giant had been a huge influence on World Trade. However, as so frequently happens, Shulman moved on (to become president of Atco), leaving the band without support in the boardroom.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Let’s face it, though: the idea of a prog band securing a major label deal in 1989 now seems unlikely in the first place. “I suppose so,” says Sherwood. “But although World Trade painted within those lines, we also dealt in fairly commercial songs of four, five or six minutes in duration. Until Derek moved on we were really rocking – our record was outselling Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe and Trevor Rabin’s album Can’t Look Away.

“I certainly don’t blame Derek at all for what happened. In fact, he was the one that introduced me to the Yes camp, so he became an integral part of my world.”

I still think we were pushing forward with a new idea of how prog could be interpreted

Produced by Keith Olsen, World Trade was a fantastic album of clashing contrasts, its lush, ambitious arrangements coloured by razor-sharp melodies. Though their back-up system would prove flawed, the band really were onto something very special. Sherwood chuckles when reminded of his own words in a band biography in which he claimed that their music “forms a link between select virtuoso bands of the past (Genesis / King Crimson / Yes / Pink Floyd) and the future of progressive rock.”

“What a grandiose statement, especially considering how young I was!” he grins. “Those names were the wells from which I have always drawn, and each band member was extremely capable within their craft. I still think we were pushing forward with a new idea of how prog could be interpreted; and the debut album remains unique in its own way. It’s stood up after all these years – you could pop it on right now and it’s still interesting and entertaining.”

Lyrically, too, World Trade were making bold statements. The same biography had Sherwood declare: “We don’t want to jam anything down people’s throats, but the time is right to express positive feelings. We want world peace and together we can achieve it. It’s that simple.”

“Nothing’s really changed, has it?” he says now. “When we named the band World Trade, 9/11 and all these things hadn’t taken place. Considering the tragedies we’ve witnessed, it’s kind of creepy that we ended up being called that – but I’ve always paid a lot of attention to what’s going on in this planet.”

Once the sales dried up, a six-year gap separated World Trade and the band’s second effort, Euphoria, which featured Squire on bass and backing vocals on two tracks. By this point, Sherwood had already co-written for Yes and toured as an additional guitarist for the Talk album. If you like Big Generator-era Yes with a pinch of It Bites, it’s well worth checking out.

I’ve been hearing I sounded too much like Yes until I actually joined Yes!

But the similarities between the groups were all too obvious, and the 1995 album surfaced via a relatively small label, Magna Carta, ensuring it didn’t get pushed. “We still called the band World Trade but Euphoria wasn’t made in the same way as the debut,” Sherwood reflects.“At the time everybody was really busy with various different projects; and I suppose it’s a bit of hotchpotch, whereas with the debut we had been laser-focused.”

And as if the band’s main point of influence wasn’t already transparent, the presence of Squire was a dead giveaway. “Oh God, I’ve been hearing that I sounded too much like Yes all the way down the line until I actually joined Yes!” Sherwood laughs. “I was right on target the whole time.”

After World Trade broke up in 1995, Gowdy and Allison went on to form Unruly Child, an AOR band whose self-titled debut is now retrospectively considered iconic; and in much the same way as World Trade, it’s kept in the drawer marked ‘cult favourite.’ There are parallels between the two groups – first and foremost, Frontiers Records resurrected the careers of both – and there was always a strong melodic rock undercurrent to World Trade.

“Harmony is extremely important to me,” Sherwood says. “As a matter of fact I sang so hard on that first World Trade record that I ended up in the hospital. So you could say that I love melody to the point of hurting myself!”

The notion of a World Trade reunion had been around since the mid-2000s, but when Frontiers came to the table there was a single important principle to agree on. “It needed to be the opposite of what we’d done with Euphoria,” Sherwood says. “Were we to do it, everyone had to commit to being the best that we could possibly be – just like the first album. And luckily our schedules parted like clouds dispersing on a bright sunny day.”

Even among the diehard proggers we were too commercial to be considered prog

Poetic metaphor aside, the overwhelming criticism of the resulting record, Unify, is that it’s simply too one-paced, the title track a rare example of stepping out of first gear. “Those are the tempos that old musicians write at,” Sherwood responds, laughing. “We’re not as bright as we once were, but we still try. You could also say that of Pink Floyd, so it is what it is. The more people listen to it, the more they’ll find.” He adds: “But on first play I tend to agree with you.”

Doubts also remain as to whether World Trade are melodic rock enough for AOR fans, or not proggy enough for the alternative camp. “I’ve always occupied that no-man’s land,” Sherwood admits. “Even among the diehard proggers we were too commercial to be considered prog. But I don’t worry too much about labels and somehow I’ve ended up in the premier prog band of all time. And now – regrettably, thanks to John Wetton dying – I’ve also become the lead singer of Asia. If I'd listened to haters I’d have stopped after the first Lodgic record.”

He owns up to some uncertainty as to whether World Trade will tour again. He hasn’t abandoned hope of playing some solo shows for his solo album Citizen, but he’s on the road in North America with Yes until late September, and of course there are also those new commitments with Asia.

Two years on, although the first tour he did was “super emotional,” he’s become a little more comfortable with the role inherited within Yes. “It was like going to a summer home in that I’d been there before,” he says. “I knew all the characters – but standing in that spot wiped me out.”

He’s “still trying to process” being onstage with Asia. “Much like the situation with Chris, who we knew wanted his band to carry on, I produced John’s last solo album [Raised In Captivity, 2011]; and as I understand, he was insistent that I should do this.

“Getting that call was a bit like lightning striking twice; now I find myself in two of my favourite bands. The arena tour with Asia has been very successful, and there’s a dialogue about keeping things moving. I’ve no doubt you’ll see more – unless there are things I don’t know.”

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.