How Haken took their love of 80s prog and made Affinity

Yes' 90125, the Transformers cartoon soundtrack and Toto were just some of the influences for Haken's 2016 album Infinty

There’s still an unmistakable sense of incredulity and excitement in the voices of Haken’s Rich Henshall and Charlie Griffiths when recalling the acclamation of their 2013 breakthrough album The Mountain. Granted, it might not have propelled the band into the mainstream arena, but with their audacious musical mix of contemporary progressive elements and a 70s Gentle Giant styling, it became their most successful recording to date. And with the prog glitterati lining up to stack commendations onto Haken and gift them sought-after support slots, it’s a period the band still reflect on with astonishment.

“Honestly, we really weren’t expecting that, or the response we got from it,” says guitarist Griffiths. “It was just one of those lucky breaks you hear about and we managed to get some good contacts from it. People like Mike Portnoy and Jordan Rudess [Dream Theater] giving your band a stamp of approval? You can’t buy that. It was a huge thing. We did a couple of cruises at Cruise To The Edge and Progressive Nation At Sea and it was just incredible. That’s not to suggest we think we’ve made it or anything, as we know it’s still going to be a very hard slog.”

Faced with such media and industry plaudits, Haken had to face the reality that there were now people scrutinising their next move. Their re-recording of three of their early tracks for the Restoration EP was effectively a stopgap, and logic would dictate that the band should be feeling under pressure to write and record a worthy successor. Yet guitarist and keyboard player Henshall claims they never felt the nagging inner questions that plague many bands, like, ‘How on earth do we follow that?’

“Well, we try not to be too conscious of what we’ve done in the past and try to treat every new album as something completely fresh,” he explains. “So we go into the writing process with no preconceptions of how we want it to sound or any pressure. We all just go to our instruments and write what we’re feeling at the time and see what comes out.”

With all members of the band being encouraged to suggest musical motifs and ideas, this was a change in their way of operating. Previously, Henshall had taken responsibility for steering the music and although the results of the new process were striking, the reality of additional musicians conceiving ideas was a potential source of conflict. Such debates may have been fiercely contested but seemingly never resulted in any tantrums, with Griffiths suggesting diplomatically that instead there were some rather intense negotiations.

“Oh yeah, there’s a lot of that in Haken,” he laughs. “There’s a lot of, how shall we put it, compromise. What we end up with is what we’ve unanimously liked, so there might be some things I really liked that didn’t make it on. But that’s partly why the album is called Affinity. It was having that unanimous harmony and empathy towards each other in the band. It was definitely more fun and I think we will continue to do it this way.

“It wasn’t really a massive difference, but previously the most convenient way to work was that Rich would come up with his starting ideas, but this time the starting point could be from anyone. So in a way it was a longer process because we were used to doing it the other way and relying on Rich, but I think in the end he just felt, ‘I can’t do it any more.’ So we shared the load. It’s definitely more conducive to a band effort.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Haken have never been predictable and Affinity sees the band’s aversion to ponderous repetition continue. Unlike their last album that had 70s Gentle Giant leanings, they’ve turned to albums recorded a decade later for their latest inspiration. But it’s not the Genesis and Floyd sound of the neo-prog acts that have provided the stimulation; rather, it’s the more commercial-sounding albums such as 90125 by Yes, King Crimson’s Three Of A Perfect Pair and even recordings by acts such as Toto.

“Everyone thinks of the 70s as being the golden era of prog, and Gentle Giant are my favourite prog band,” says Griffiths. “But at the same time, when we’re on tour, we love listening to 80s music and there were some awesome prog albums. I know I’ll probably be strung up by the prog community for admitting it, but 90125 is my favourite Yes album. That’s the one I always go to and we play it a lot on the tour bus. I just love the drum and the keyboard sounds, the vocal production and the harmonies on there.

“When King Crimson did Three Of A Perfect Pair, which is equally 80s-sounding from a production point of view, nobody could call it cheesy or anything as it’s serious music. So rather than do the 70s thing, we wanted to see what would happen if we used that 80s sound mixed with the modern. I liked the way it came out.”

For all those commercial prog albums from the 80s that Haken cite, they’ve also delved into the movie soundtracks of that era for sources of sounds to guide their approach. Both Griffiths and Henshall reference the works of American composer and arranger Vince DiCola, writer of the Training Montage for Rocky IV. He was also heavily involved in creating the soundtrack for Transformers: The Movie.

The latter would certainly appear to be an unusual bedfellow for a prog band, with its roughly drawn cartoon figures being probably the first time a rather corny animated children’s film has ever stimulated the writing on a prog rock album.

“The Transformers soundtrack is quite a strange influence but I reckon if people actually listened to it, they’d think it was amazing stuff,” argues Henshall. “It translates so well. It’s a crime that DiCola isn’t as well recognised as he should be. He’s a hugely talented guy and has recorded some of the best stuff I’ve ever heard.

“There were other soundtracks like Flight Of The Navigator and also The NeverEnding Story, which has an over-the-top, cheesy sound, but it’s quite nostalgic and taps into a certain emotion. We thought it would be great to fuse the modern sounds with a lot of that synth-based stuff they were coming out with in the 80s. Yes, it’s risky and could completely turn people off, but you can’t worry about these things. In the past there have been a lot of quirky moments so you’ve just got to write it and hope that people like it.”

These 80s influences are cleverly integrated into the album, always used when necessary to add an unexpected direction and they never become too distracting. The initial spark of the idea came with Griffiths working on the track 1985, which, with sharp electronic drums, opulent keyboards and extended instrumental sections, neatly encapsulates the band’s ideology. Elsewhere, those nostalgic flashes are kept in check to ensure the concept doesn’t become overly gimmicky.

“I think the track 1985, which has a rather unsubtle title, was my initial idea,” says Griffiths. “I kind of programmed the drums in a light‑hearted way and put in some of the 80s drum sounds. The guys took it at face value and were into it. We’re always listening to that stuff on the bus and Diego [Tejeida] the keyboard player is really into creating sounds and sound design, so he had a lot of fun going back to that.

“There’s also Earthrise, which is our version of a Toto song, which admittedly still wasn’t very Toto. We originally tried to have the sound on every song but it just felt a bit too forced, so we’ve used it sparingly when it felt appropriate as we didn’t want it to seem jokey. I mean, we do want to sound like a modern band.”

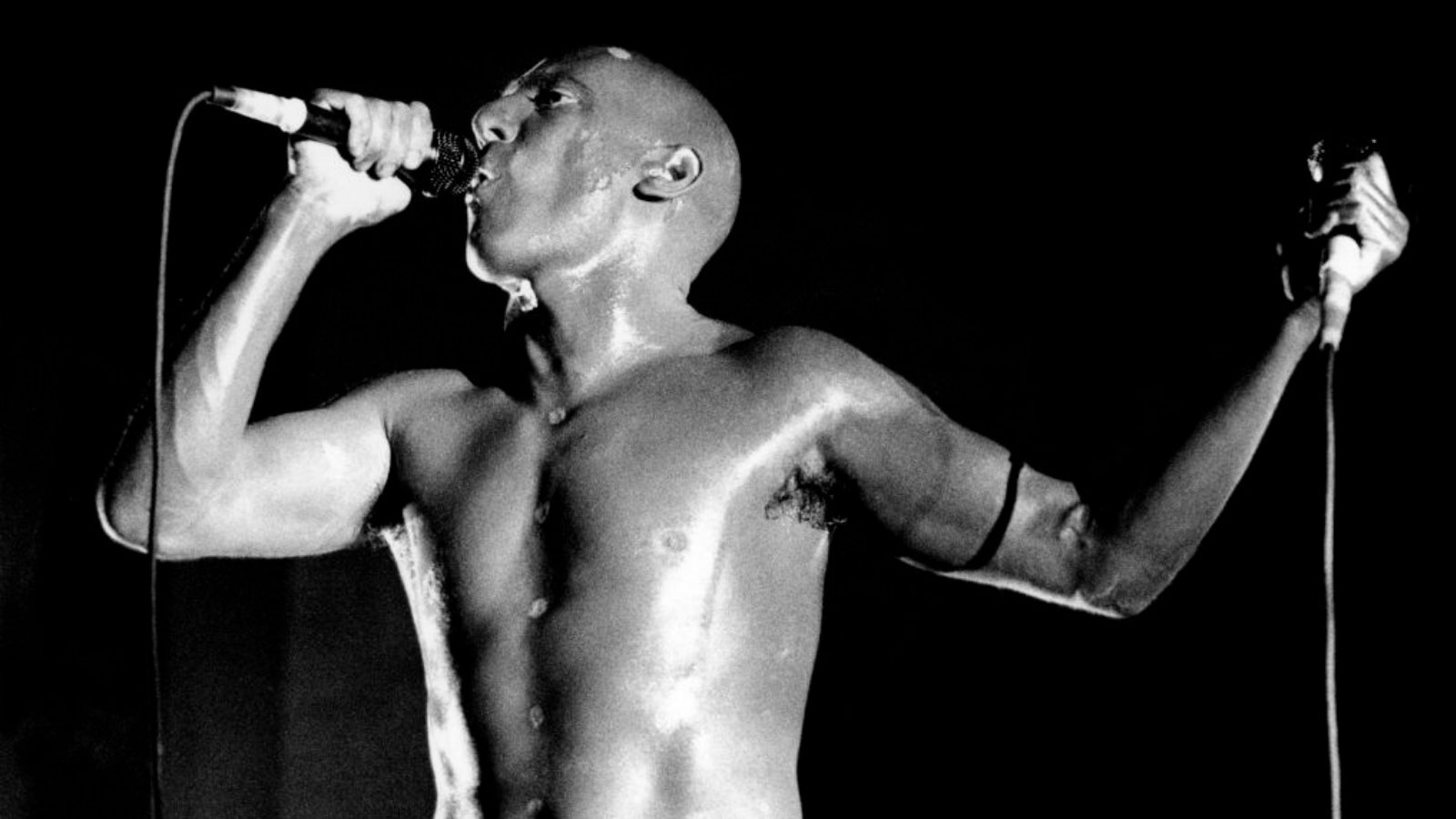

As Griffiths rightly surmises, it’s not an album that merely relies on nostalgia, and the musicianship is at times breathtaking. That’s evidenced on the album’s 15-minute centrepiece The Architect, which aside from the epic qualities Haken have always been adept at creating, boasts a fleeting segment of black metal, with Leprous singer Einar Solberg adding his distinctive growls.

“We couldn’t be happier with Einar’s screaming on that,” says Henshall. “We did a UK tour with Leprous and every night we were watching him do his thing and we were just awestruck by how brutal it sounded live. We thought he would be ideal and he’s pulled it off. We’ve tried screaming before on the Aquarius album and it had mixed reviews. Some people were turned off by the whole thing, others loved it. But it’s only a fleeting moment, and the fact is that if people don’t like it, it’ll be gone in a minute and they’ll have the rest of the album to enjoy.”

Haken’s confidence appears to be unshakable, but there is of course the possibility that existing fans might be deterred by those growling vocals and the wistful sounds and production values from three decades ago. The band may want listeners to enjoy Affinity but it seems they weren’t overly concerned about the audience reaction when writing the album, arguing that the music was made for their own self-gratification.

“We just write music we like as we’re going to have to play it,” states Henshall. “At the same time, we want people to like it, but that shouldn’t drive the music in any way. If you think like that, it starts to become a bit dishonest. I think that would be the beginning of a downward spiral in any band. So you have to write what feels right for you as that’s the most honest way of composing.”

“Yes, we’re very headstrong and that was the last thing on our minds,” adds Griffiths. “You can’t second-guess what someone is going to like. All you can do is record something you like and that’s really the only way you can make authentic music. Just getting the six guys in the band to agree on something is the hard bit, so having an imaginary seventh person in there really wouldn’t be helpful.”

This article originally appeared in issue 65 of Prog Magazine.