The 50 best Led Zeppelin songs

Led Zeppelin may have shunned singles, but they wrote some of rock's most iconic songs – and here are 50 of the very best

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Led Zeppelin. Even at this distance, it's a name that somehow conjures up majesty. Formed at the back-end of the British invasion, they somehow made everything bigger, bolder and brasher than it had been before. They were the first genuine rock gods, with the hair to match and an apparently endless appetite for the perks that come with being young, pretty and imperiously talented.

Over the course of eight albums (and no UK singles), they delivered the unexpected with unearthly precision, able to switch from towering, almost other-worldly epics like Kashmir to the gentle, bucolic folk of That's The Way. While rooted in the blues (let's not go there, OK?) they became something else over the course of a dozen years, taking music into bigger buildings than it had before and playing at a higher volume than was perhaps necessary.

In every respect, they were huge. They had their own plane, for chrissakes. And, in 2025, they finally got their own film, Becoming Led Zeppelin. Typically, it was formatted for IMAX.

At their heart were four extraordinary musicians: the untouchable John Bonham drove the ship forward. Bassist and keyboardist John Paul Jones was a beautiful anchor. Guitarist Jimmy Page orchestrated it all, wrangling everything into shape. And, out front, Robert Plant just wailed.

These are Led Zeppelin's 50 best songs.

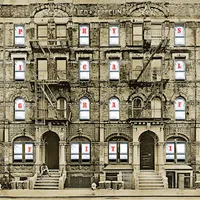

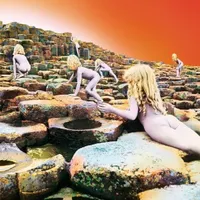

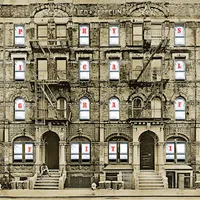

50. Custard Pie (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

There's a compelling case to be made that Physical Graffiti is the greatest double album ever recorded. Led Zep's sixth studio recording, there’s a feral mystery to it even today – and opener Custard Pie lets us know what we’re in for. Its menacing, salacious riff is driven by intoxicating dirty blues, while the unapologetic mutant funk rhythm section of Bonzo Bonham and John Paul Jones buffalos a path through the fray.

Wha-wha clavinet snakes around razor-sharp guitars, while Robert Johnson, chicken blood and smoking valve amps are all invoked and teleported into leafy Barnes’ Olympic Studio 2. It’s aural carnage – in the best possible way.

49. Houses Of The Holy (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

Regarded as the ‘lost track’ from the original Houses Of The Holy album, which had been released two years previously, this tune’s clipped beat and easy riff provided a platform for some of Jimmy Page’s most manic improvisations. The ‘houses’ in question here do not refer to a particular church, temple or chapel, but were meant to describe the spiritual aura that the band felt was often created at their best concerts. Not the controversial ones where fire crackers and tear gas were let off, but at those halcyon hippie festivals, where the scent of newly smoked grass would pleasantly waft across the sunlit fields.

Those with keen hearing will detect the sound of John Bonham’s bass drum pedal squeaking. The song was recorded in the days before the introduction of the WD40 spray can. The piece was recorded and mixed at Olympic and Electric Lady during a session that dated back to 1972.

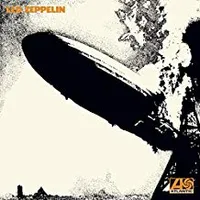

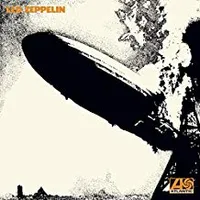

48. Your Time Is Gonna Come (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

It still may have only been October 1968, but Zep laid down the blueprint for ’70s macho excess on this vitriolic kiss-off to an ex-lover. John Paul Jones’ cathedral-like organ intro sets a suitably epic tone, before Bonham’s sledgehammer drums and Page’s bluesy pedal steel guitar – his first use of the instrument, fact fans – set the scene for Plant’s lung-busting takedown of a former girlfriend ('Lyin’, cheatin’, hurtin’/ That’s all you seem to do') prior to a climax featuring all four members in a hypnotic choral fade-out.

Curiously never played live after their Scandanavian tour of the same year, it's an early example of Zep flexing their musical muscles – their time was about to come.

47. Bron-Y-Aur Stomp (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

For a band synonymous with heaviosity, Zep still had their lighter moments. A case in point is this folksy singalong, written on a whim at the band’s cottage about Plant’s love for walking his pet dog, Strider.

Deceptive in its simplicity, it combines the singer’s obvious love of its canine subject ('Tell your friends all around the world / Ain't no companion like a blue-eyed Merle') with a homespun rhythm featuring Bonham on spoons and castanets and Jones on acoustic bass. With Page’s lead lines providing a propulsive energy, it's doggone proof that anything The Beatles could do (see Martha My Dear), Zep could do, too — and with added bite.

46. Travelling Riverside Blues (single, originally recorded 1969)

Page and Plant might have been the priapic pin-ups, but it was Bonzo and John Paul Jones’ rhythm method which provided Zep with their sexual heat. Proof comes in this sublime reimagining of Robert Johnson’s blues classic. Originally recorded specially for John Peel's Top Gear radio show in 1969, it remains one of the band’s most integrated performances, Page’s liquid slide and Plant’s cryptic ad libs ('Why doncha come in my kitchen?') hot-wired to a sizzling funk groove.

It may have been overlooked at the time, but Page never forgot its magnetic allure, the song re-emerging form the Delta swamps as a bonus track on 1990's box set of the Complete Studio Recordings.

45. That's The Way (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

The story of Plant and Page’s regenerative trek to Wales looms large in Zeppelin folklore, and the Led Zeppelin III sessions were indeed important – they gave Page chance to spread his wings but, crucially, Plant the opportunity to grow as a songwriter. No longer forced to simply beat his chest and crow about the size of his knob, he wrote his first truly great lyric for That’s The Way.

Amid Page’s cascading acoustic guitars, dulcimer and weeping pedal steel, Plant weaves a mournful southern Gothic tale on a par with Bobbie Gentry’s 1967 hit Ode To Billie Joe. With its haunting ambiguity, the song could be about class, racism, homosexuality or even ecological disaster. It’s sophisticated, secretive and flat-out beautiful. And, Lord knows, it’s a far cry from ‘I’m gonna give you every inch of my love’. Plant has said the third album was “incredibly important for my dignity”. Perhaps the same could be said for the entire band.

44. Tea For One (Presence, 1976)

The pulverising opening guitar riff might mimic the adrenalised thrill of live performance, but as Tea For One unravels over a hypnotic nine-and-a-half minutes, the sobering reality of life on the road becomes clear. Written by Plant in the breakfast room of a New York hotel, the singer's jet-lagged vocal ('How come 24 hours, baby, seem to slip into days?') encapsulates the creeping horror of tour fatigue.

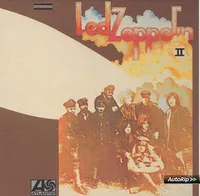

However, it’s Page's extended solo, drenched in existential ennui, which nudges this under-rated gem into the stratosphere, his lead lines evoking the disorientating blur of anonymous hotel rooms, fast friends and soul-sapping overnight drives that come as baggage with global stardom. Loneliness never sounded so exquisite.

43. Moby Dick (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

Led Zeppelin were lucky to have John Bonham as their drummer. Apart from being Plant’s mate, his presence gave the band a unique sound and authority. He also used to perform a spectacular solo that would often last 20 minutes, which became a feature of the band’s increasingly extended concerts. During these sessions, Bonham would play with his bare hands, attacking a huge flaming gong, reaching a climax that had crowds roaring. Moby Dick was first aired on Led Zeppelin II.

Jimmy Page established an appropriate riff to launch the number, which kicked off with a battering snare drum figure. Bonham moved from snare to tom tom triplets and congas using his hands. The Ginger Baker-esque climax when he switched to sticks still sounds impressive, but this studio version lacked the fire a ‘live’ audience would encourage.

42. Bring It On Home (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

Recorded at Mystic Studio in LA in May 1969, this deceptively arranged final cut on Led Zeppelin II appears, for almost two minutes, to be nothing more than a narcoleptic homage to Sonny Boy Williamson’s blues of the same name before exploding into life. What follows is a blueprint for the globe-dominating decade to come, Page’s intricately woven guitar parts and Bonham’s funk-infused drums offset by Jones’ melodic bass runs and Plant’s primal invocations to be recognised as ’70s pop's premier Rock God-in-waiting: 'I’ve got my ticket, I’ve got that load.'

Not exactly Led Zep's most famous case of questionable copyright, but because there was no case to answer, composer Willie Dixon has been listed on the writing credits to this song since 1972.

41. You Shook Me (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

It may never have appeared on Jeff Beck’s Spotify – he was legendarily peeved on hearing it, having released a similar arrangement a couple of months earlier on 1968 solo album Truth – but Zep’s orgiastic take on Willie Dixon’s standard rightly took the plaudits.

Built upon Bonham and John Paul Jones’ titanium-strength slow groove – Jones also supplies scintillating solos on both electric piano and Hammond organ – it finds a fired-up Zeppelin flagging up their blues credentials. With Plant’s squalling harmonica and larynx-busting vocal matched by Page’s grinding guitar, it puts the original through the shredder, building to a feverish finale where Page’s groundbreaking use of backwards echo is matched by Plant’s eye-watering vocal howls. The result? A very different kind of blues.

40. Trampled Under Foot (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

Physical Graffiti produced not only the Led Zeppelin anthems Kashmir and Houses Of The Holy, but it also the delightfully upbeat, out-of-character Trampled Underfoot. The keyboard-orientated theme provided a whole new groove for the band, which stunned fans who heard it being played at the 1975 Earls Court concerts. It had the kind of relentlessly driving rhythm that no one wanted to stop.

John Paul Jones set up the electric piano riff and Bonham supplied the surging backbeat. Although Stevie Wonder may have provided the inspiration, the attack was certainly all Zeppelin. Trampled Underfoot emerged from an informal jam session, and rapidly became one of Plant’s favourite tracks. The lyrics are said to be based on Robert Johnson’s 1936 vintage Terraplane Blues. The song uses motor cars as a sexual metaphor – 'Mama, let me pump your gas'. Trampled was released as another US single and reached number 38 in the Billboard chart in May 1975.

39. In The Light (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

Once described by Jimmy Page as the follow-up to Stairway To Heaven, this Physical Graffiti standout had its origins in a breezy rehearsal ditty called In The Morning.

The end result is a far weightier proposition, John Paul Jones’ foreboding, drone-like synth intro marking the start of a rollercoaster eight-minute journey where nocturnal introspection ('And If you feel like you can’t go on / And your will’s sinking low') and nerve-shredding heavy riffing eventually give way, courtesy of Jones' breezy organ part and Page’s glissando guitars, to a gorgeously sunlit finale. By turns unsettling, eerie and ultimately euphoric, it's a prismatic gem – not so much rock, as marble.

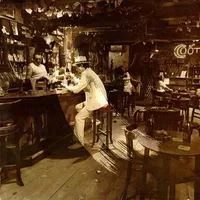

38. In The Evening (In Through The Out Door, 1979)

Jimmy Page may have taken a back seat to Robert Plant and John Paul Jones in the recording of Zeppelin’s final studio album, In Through The Out Door, but on this strutting opening track, he stamps his authority on proceedings. The slamming door effect of the solo is yet another innovation. Washed up by 1979? Not on this evidence.

37. Nobody's Fault But Mine (Presence, 1976)

Credited to Page and Plant on March 1976’s Presence – despite the fact Blind Willie Johnson wrote the lyrics in 1927 – this spine-tingling blues belter is an example of rock’n’roll grandstanding at its finest. Over an air-tight rhythm section Page and Plant trade the spotlight, the former’s fire-and-brimstone riffing matched every inch of the way by the latter’s vocal gymnastics, a demonic harmonica solo from Plant upping the ante further still.

Lyrically, it subverts the song’s original religious theme, invoking Robert Johnson's Hellhound On My Trail with the lines: 'Got a monkey on my back / Gonna change my ways tonight'. An allusion to Page’s burgeoning heroin habit or their own notoriety as rock's debauched ruling class? Hard to say, but with the punk armies amassing to dethrone them, this is the sound of Zep at both their murkiest and most magisterial.

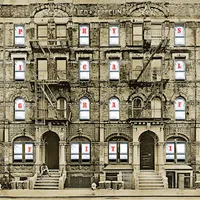

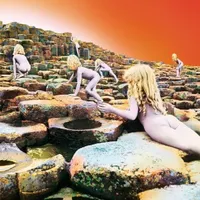

36. D'yer Mak'er (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

The title might have been filched from an old music-hall joke (‘My wife’s gone to the West Indies…’ etc), but this Houses Of The Holy track was originally Plant’s attempt at a 50s doo-wop pastiche. He was keen to release the reggae-tinged track as a single – Atlantic even distributed promo copies to DJs – but not everyone was so keen on it. John Paul Jones was vocal in his derision of the track.

“A real love it or hate it track, which I still love,” producer Eddie Kramer told Classic Rock in 2017. “Those huge drums that kick in at the start are like bombs going off. What’s amazing, though, is how John Bonham keeps the bombs going off while playing this extraordinarily subtle and brilliant rhythm. Robert’s voice is also superb, kind of a meeting of doo-wop and reggae.

All credit must also go to Jonesy, whose bass takes the reggae rhythm to a whole different place. I could go on about this one for hours. Suffice to say nothing like it had ever really been attempted by a rock band before, and it caused a lot of controversy when people first heard it.”

35. What Is And What Should Never Be (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

The initial recording sessions for what would become Led Zeppelin II saw the band working on What Is And What Should Never Be, a drifting, melodic song that would highlight Robert Plant’s growing maturity as a lyricist.

For all their hard rock legend it’s diversity that has kept Led Zeppelin’s name in lights – the psychedelic-metal-prog riffs here are almost as astounding as Plant’s vocal; no wonder he keeps this one close when he plays his solo shows these days.

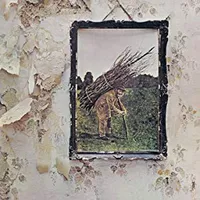

34. Misty Mountain Hop (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

An uplifting outing, with John Paul Jones’ electric piano providing the central riff motif the song revolves around. John Bonham makes an exemplary contribution, with some riotous fills.

Plant meanwhile is back on the hippie trail telling the tale of being busted in the park with ‘crowds of people sittin' on the grass with flowers in their hair – hey boy do you wanna score?’

33. Tangerine (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

The Jimmy Page composed Tangerine was first recorded in April 1968 at the final Yardbirds recording session under the title Knowing That I’m Losing You.

There were also several songs begun there that would find a home on their next four albums, including the bare bones of Stairway To Heaven, Over The Hills And Far Away, Down By The Seaside, The Rover, Poor Tom and (similarly misspelt) Bron-Y-Aur. Tangerine, with its nicely low-key, deliberate-mistake intro, was eventually reborn in Wales as part of the Led Zeppelin III sessions, as a country-tinged, Neil Young-inspired dirge.

32. The Lemon Song (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

Recorded virtually live at Mystic Studios in Los Angeles in May 1969, during their second US tour, this full-blooded reboot of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor feels like the sound of pop’s tectonic plates shifting.

With Jones' tightrope-taut bassline providing a precarious counterbalance for Page’s savage lead lines and Plant’s libidinous howl, The Lemon Song shimmers with West Coast sleaze, the singer’s not-so subtle appropriation of Robert Johnson’s sexually charged lyric 'You can squeeze my lemon 'til the juice runs down my leg' enough to send the prudish into freefall. The era of Whole Lotta Love – during which Plant would later reuse the phrase – had been set in motion.

31. Gallows Pole (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

Based on a traditional folk tune popularised by Leadbelly – Page first heard it performed by Californian folk singer Fred Gerlach – Gallows Pole recounts the story of a man pleading for his execution to be delayed until his friends arrive with the hope of a possible reprieve.

From such ancient fare Zep conjure up a sizzling down-home boogie, Page’s layered instruments – banjo, acoustic, 12-string and electric guitars – and Jones’ mandolin and bass conjuring up a medieval menace before Bonzo wades in and Plant ramps up the tension until a frantic call and response finale. Swinging, in every sense.

30. Communication Breakdown (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

Recorded in September 1968 and originally released in the US as the flip-side to debut single Good Times Bad Times, Communication Breakdown is now recognised as one of rock’s pivotal primal screams – a sonic stepping stone to both punk (The Ramones and The Damned were fans) and heavy metal.

Yet while Breakdown has its roots in antiquity – it was inspired by Eddie Cochrane’s 1957 hit Nervous Breakdown – it also holds up a (shattered) mirror to the turbulent times, Page’s lacerating guitar and Plant’s lupine howl as incendiary as the student riots sweeping Europe in protest at the Vietnam War.

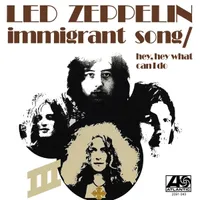

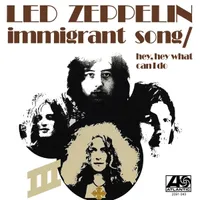

29. Hey, Hey, What Can I Do (single b-side, 1970)

Though undoubtedly leveraged into its high standing due to its relative unavailability – B-side to Immigrant Song in 1970, not reappearing until 1990’s box set – there’s something awe inspiring about a band who can afford to side-line such obvious riches.

John Paul Jones adds acoustic guitar to his Zeppelin CV, his mandolin and bass already driving the track, and Plant’s woman woes take centre stage, again.

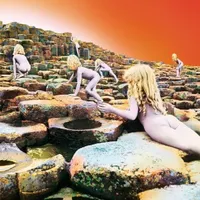

28. The Ocean (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

The final track on Houses Of The Holy. Although this record is viewed by some critics as the band’s least satisfactory mid-term work, it yielded The Song Remains The Same, as well as The Ocean. This tune is a heavy blues rock anthem, which features Jimmy Page’s typical, no-nonsense minor pentatonic riffing that has inspired several generations (it was even sampled to great effect on the Beastie Boys’ first album, Licensed To Ill).

The song kicks off with John Bonham audibly counting in the beat and uttering the immortal line 'We’ve done four already, but now we’re steady, and then they went 1, 2, 3, 4…' The drum attack is particularly savage on this track, and the guitars cut through it all with a vibrancy that was years ahead of its time.

It was partly recorded at Electric Lady Studios in New York and the rest was done at Olympic in London. Although the edits aren’t obvious, there’s a distinction between the two sections. The first part is uptight and funky, then The Ocean unexpectedly moves to a swinging sequence, with Bonham switching to a big-band style that fills behind Page’s superb jazz solo. Robert’s lyrics are matched by rare backing-vocals from the rhythm section.

Plant finally explained the song is dedicated to his then three-year-old daughter, Carmen.

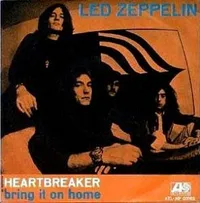

27. Heartbreaker (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

Although the latter part of Led Zeppelin II was somewhat uneven, Heartbreaker was among the highlights. The fifth track was recorded and mixed at the A&R studios in New York and showcased one of Page’s most exciting and memorable guitar outbursts.

Robert’s question – 'Hey fellows, have you heard the news?' – sets up a dynamic groove, which the band supports. The band even stops dead in its tracks to allow Page to explode all over his fretboard, before drums and bass clamber back. The guitar picks up speed as Page piles climax upon climax. After an abrupt halt, Plant returns to continue his diatribe: 'You abused my love a thousand times!'

The song became one of the favourites for the band to perform live from October 1969 onwards, and was used as a set opener, alternating with Immigrant Song. Jimmy would extemporise at length during his Heartbreaker solo, often quoting from Greensleeves or from themes by Bach.

26. The Rover (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

Page can do bombastic, he can do blues, he can do 50’s rock’n’roll and he can definitely do guitar melody as well as anyone. The solo on this underrated gem is ample proof. The Rover was originally worked on during the Zep III sessions, but eventually issued on subsequent Zep album Physical Graffiti instead.

25. How Many More Times (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

It may owe substantial debts to both Albert King’s The Hunter and Howlin’ Wolf’s How Many More Years, but this nightmarish eight-and-a-half-minute closer to Zep’s debut album has a dark heart all of its own.

Opening with a stinging burst of wah-wah guitar, Plant’s carnivorous vocal ('I was a young man, I couldn’t resist') and Page’s eerie bowed guitar – a nod to his days in The Yardbirds – combine to establish the maleficent mood before the song develops into a molten rolling blues, as chilling as it is awe-inspiring.

24. Fool In The Rain (In Through The Out Door, 1979)

The Caribbean feel of Fool In The Rain is initially reminiscent of D’yer Mak’er played backwards. For a moment guitar and keyboards link up to follow the stumbling-but-progressive riff in tandem, and the results are… charming. But should we be using the word ‘charming’ in relation to Zeppelin? Probably not. There’s a high-pitched whistle after about three minutes, and a salsa beat kicks in. Plant’s refrain ‘Light of the love that I’ve found’ lodges in your brain.

An outstanding Bonham showcase from Zeppelin’s studio swansong, Fool In The Rain highlights the fusion influence of such jazz giants as Bernard Purdie and Alphonse Mouzon. Clock the percussive perfection at two minute 25 seconds when a blow of a whistle ushers in a Latin samba delight.

23. The Song Remains The Same (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

Upon release in 1973, this track was just the latest in a string of classic Zeppelin album openers. Prior to album sessions, this song was rehearsed with the working title Worcester And Plumpton Races – a reference to Page and Plant’s respective homes. When they worked on it in the studio, that title was changed to first The Overture and then The Campaign. It was only when Plant started scribbling verses for it that it ceased to be an instrumental and became his paean to the music of the world, whatever form it takes.

“The whole album had a very upbeat quality to it,” producer Eddie Kramer told Classic Rock. “You can hear that straight away from this opening track. A much brighter sound than on earlier Zeppelin albums. There was a unity of spirit and a unity of direction of sound. A lot of that had to do with Pagey and the fact he had a very clear idea of what he wanted. I believe Jimmy later had Robert’s vocals speeded up a bit so that they become another layer to all those gorgeous guitars."

22. The Battle Of Evermore (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

Based on a tune written late one night at Headley Grange by Page while messing around on Jones’ mandolin, Battle Of Evermore’s improbable blend of mythical allusion and Scottish folklore achieves an otherworldly grace thanks to Plant’s Arthurian lyric ('I’m waiting for the angels of Avalon / waiting for the eastern glow') and Sandy Denny’s ethereal vocal – impressive enough for the band to award her her own symbol on the album’s sleeve.

None of which explain’s Evermore’s unique allure, a masterpiece of musical storytelling where you can almost hear 'the horses thunder, down in the valley below'.

21. All My Love (In Through The Out Door, 1979)

All My Love is plain beautiful. With Page notably absent from the songwriting credits, Plant offers a paean to his deceased son in a song steeped in fond remembrance.

You can’t help but giggle at the way Bonzo tries to heavy it up about halfway through. Page takes a noodling role, but unlike some of his other more meandering interludes, this time it’s somehow to the benefit of the track, not its detriment. Plant is on top form as he whispers the emotionally-charged words: ‘All of my love… to you now.’

20. Good Times Bad Times (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

Right from the dramatic two beat opening, John Bonham leads this track and puts the whole kit through its paces. That pioneering use of bass drum triplets heralded the arrival of a very special drummer. Doing things with a bass pedal that it took two of James Brown’s drummers to try and emulate – and they knew a bit about rhythm.

Rolling Stone cited this song when they named John Bonham as the world's best drummer in 2016, saying: “Jimmy Page was still amused by the disorienting impact that Good Times Bad Times, with its jaw-dropping bass-drum hiccups, had on listeners: ‘Everyone was laying bets that Bonzo was using two bass drums, but he only had one.’

Heavy, lively, virtuosic and deliberate, that performance laid out the terrain Bonham’s artful clobbering would conquer before his untimely death in 1980."

19. Thank You (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

Marking the point where Plant grew into himself as a lyricist (Page: “I always knew he would”), and delivering a cracked, heartfelt paean to his wife – even if it was part motivated by guilt – there’s also some highly effective pop nous on the chorus here, curiously bolstered by Page’s relatively weak backing vocals.

Widely covered, versions range from the surprisingly great (Duran Duran), the idiosyncratic (Tori Amos), to the quick-call-the-police (Fred Durst, Wes Scantlin).

18. Going To California (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

The Hollywood hiraeth felt by Page and Plant while ensconced in rural Wales manifested itself in an unadorned love letter to Joni Mitchell and other notable blissed-out dwellers of Laurel Canyon.

Plant’s near-naïve reflections on his sun-kissed introduction to the state’s enchantments adds acres of charm and pathos belying his tender years. Iced by Page’s modal drone-picking and Jones’ gossamer mandolin, the version on 2003’s DVD (Earls Court, ‘75) in particular is a thing of wonder.

17. Over The Hills And Far Away (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

One of the features of Houses Of The Holy that producer Eddie Kramer identified to Classic Rock in 2017 is how most of the tracks have their own boutique ending: the orgasmic ‘Oh!’ at the end of The Song Remains The Same; the echoing guitar at the climax of The Rain Song. Over The Hills And Far Away (originally titled Many Many Times) finishes with a similar coda, created by Page using a reverb guitar effect with Jones’s keyboard part.

“I can’t remember exactly, but I think it was something I suggested at the mixing stage,” said Kramer. “I used to do something similar with Hendrix sometimes – fade the track out, then bring it back, like an extra breath.” What really makes this track, though, he said, “is that it really shows off the Zeppelin preoccupation with light and shade, acoustic and electric”.

16. In My Time Of Dying (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

The fertile sessions for Led Zeppelin’s Physical Graffiti album produced a number of landmark songs, including In My Time Of Dying and Kashmir.

This marathon work-out reaches a zenith around the seven minute mark – that’s the point Bonzo conjures up a barrage of brutal power of the kind other drummers can only dream of. Fittingly, his son Jason did the track justice at Zeppelin’s one-off reunion in 2007.

15. The Rain Song (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

If there’s one Zeppelin song that unites people in its greatness, then it’s this smouldering, otherworldly epic. Page wrote it in response to a conversation he had with George Harrison, in which the former Beatle asked why Zep never did any ballads.

Working on demos for the album at his Plumpton studio, Page came up with this epic-in-waiting with the tongue-in-cheek working title Slush – incorporating a subtle use of the opening notes of Harrison’s Something into the arrangement. At one point it was intended to have been a further extension of The Overture, but that changed when Plant added lyrics and it was retitled The Rain Song.

14. Ramble On (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

An early reveal of the band’s beloved light/shade dynamic, Plant’s somewhat random conflation of Tolkien references with the odd tokenistic fair maiden chucked in might not make much narrative sense, but has proved to be a rock radio staple for decades.

Speculation on the gently propulsive rhythm under Page’s percussive acoustic has been whittled down to John Bonham tip-tapping on either a sofa, his knee, or a guitar case. The smart money is on the latter.

13. Babe I'm Gonna Leave You (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

In the last decade or so, the songwriting credits on several Zep tracks have been revised to include the composer of the track that gave Page & Co. their initial inspiration – "initial inspiration” being a term used very loosely here – after the blues community raised an eyebrow and pointed out that many of the songs they'd credited to themselves were in fact long-serving standards.

So, eventually, Anne Bredon’s name was added to the credits of Babe I’m Gonna Leave You (why? Well, she only sorta wrote the damn song).

Robert Plant actually admitted to the Guardian in 2017 that he thinks his vocals on this 1969 track are "horrific". “I realised that tough, manly approach to singing I’d begun on You Better Run wasn’t really what it was all about at all. Songs like Babe I’m Gonna Leave You… I find my vocals on there horrific now. I really should have shut the fuck up!” Sounds alright to us, Robert.

12. Rock And Roll (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

An instantly identifiable Zeppelin anthem, this track came out of a jam with Rolling Stones’ mentor Ian Stewart guesting on piano. Bonzo played the intro of Little Richard’s Keep A Knockin, and Page quickly added a suitable 1950s type riff.

Fifteen minutes later, the nucleus of Rock And Roll was down on tape and a classic was born.

11. Ten Years Gone (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

Zeppelin’s creativity was at an all-time high during the Physical Graffiti sessions. Even now, Ten Years Gone is still spellbinding. Our astronaut alchemists nearing the end of their quest, heroin-soaked, cocaine-addled. Lost in the desert, wheels spinning in the sand.

The struggle is beating them down, you can hear the weariness in the voice and beats, the end is near. It is prophetic, as the band arguably struggled to scale these heady heights again.

10. No Quarter (Houses Of The Holy, 1973)

The only studiedly ‘down’ track on Houses Of The Holy, No Quarter was first tried out at Headley Grange during sessions for Zeppelin’s fourth album, at which time it was much faster than the final versions. On Houses Of The Holy, it was John Paul Jones’s personal showcase.

“This was the album where Jonesy really came into his own, and this is the track that proves it,” producer Eddie Kramer told Classic Rock in 2017. “I wasn’t there when they finally recorded it, but they had demo versions of it going back a few years. It really demonstrates that Led Zeppelin could do anything they turned their minds to now – and do it better than anybody else.

"They were able to really stretch out now and experiment, which allowed the space for Jonesy to come in and do his thing on the arrangements. It wasn’t just his brilliance as a keyboard player or even a writer, it was also the subtlety of his arrangements, and the economy of notes that made this track such a powerful statement. Genius.”

9. Dazed And Confused (Led Zeppelin, 1969)

In 1967 the Yardbirds with Jimmy Page played the Village Theatre in New York, supported by folk singer Jake Holmes, who’d just released his debut album, The Above Ground Sound Of Jake Holmes. Bass player Chris Dreja remembers Page coming back to the hotel with a copy of the album and enthusing over the track Dazed And Confused.

The Yardbirds worked up the song and added it to their set, and at some point rookie guitarist Jimmy Page produced a violin bow that he proceeded to viciously employ on the strings of his over-cranked Fender Telecaster. It was a gob-smacking gimmick, but it represented a tantalising glimpse into rock’s future.

With this single flamboyant gesture, Page was sweeping aside the studious purism of mid-60s blues austerity and flinging open the door to the grandiose gestures and limitless possibilities of titanic 1970s mega-rock. It also provided Page with his broadest canvas for live extemporisation.

8. Black Dog (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

One of the heaviest of all the great Zeppelin riffs, Black Dog’s title has often been the subject of speculation. It has been suggested the ‘black dog’ was the depression that hung over John Bonham in particular, after a hard night’s partying. Others have claimed that it was simply named after a dog that was seen lurching around Headley Grange.

The somewhat doomy mood of this all-powerful rock tune was enhanced by the location it was played in. The basic track was recorded in the crypt, and the blues style call-and-response between Plant and Page works wonders. 'Hey, hey Mama/Said the way you move/Gonna make you sweat/Gonna make you groove!'

The whole band answers this particularly sweaty, sexy bellow with a unison statement that certainly recalls Fleetwood Mac’s song, Oh Well.

A funky groove from Bonham lifts Black Dog out of its blues roots. Page’s riff is basic, but self assured, as he jams over an odd time signature (4/4 is offset by 5/8). John Paul Jones devised the theme and the arrangement on which Jimmy overdubbed no less than four guitar tracks, using a Gibson Les Paul played through a DI box.

John Paul Jones remembers Bonham had problems with Black Dog. “I told him to keep playing four to the bar, but there is a 5/8 rhythm over the top. If you go through enough 5/8s it arrives back on the beat. Originally, it was more complicated, but we had to change the accents for him to play it properly."

7. Immigrant Song (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

This tune was recorded in Olympic Studios, London, in the summer of 1970, where Jimmy and John Bonham laid down the backing tracks to Immigrant Song inside a small, low ceilinged room that looked more like somebody’s private den than a high-tech studio.

The song was just an untitled piece, a relentless, pounding theme, hypnotic in its intensity… Jimmy was slouched over his guitar while Bonham crouched over his kit, glaring at the snare drum. He wasn’t a man to be interrupted while concentrating on a new riff. If Bonham took one thing seriously, it was pleasing his guitarist with the right kind of beat. The pair always worked closely, and Bonham’s propulsive pattern soon helped to shape this unlikely Viking saga.

It had been inspired by a trip to Iceland in June that year when Robert Plant became intrigued by Nordic myths and legends. The tune was unveiled at the Bath Festival in June when the band played in front of 200,000 fans.

Jimmy wore his country yokel’s hat and Robert’s beard made him look like a Viking who’d just arrived by longboat. Immigrant Song was released as a single in the US, coupled with Hey, Hey What Can I Do in November. It went on to claim the number one hot spot during a 13-week run in the Billboard chart.

6. Achilles Last Stand (Presence, 1976)

Having used up their backlog of material on Physical Graffiti, songs for the album that followed would have to be built from the ground up. One of the first to take shape was Achilles Last Stand, the lengthy opus that would eventually open Presence.

Built on the sort of strident, all-hands-on-deck guitar figure that Iron Maiden would later build a whole career out of – Page attempting to create something, he said, that reflected “the façade of a gothic building with layers of tracery and statues” – Achilles Last Stand also featured the first of a string of intensely autobiographical lyrics Plant now felt compelled to write.

Originally nicknamed The Wheelchair Song, the subject in this instance was the enforced exile which had forced the band to become what Page later described as “technological gypsies”, and led indirectly, Plant seemed to suggest, to their current malaise – ‘the devil’s in his hole!’ he wailed balefully.

Page later described his guitar solo as “in the same tradition as the solo from Stairway To Heaven”. In truth, few would now agree but, “It is on that level to me,” he insisted.

5. Since I've Been Loving You (Led Zeppelin III, 1970)

Originally earmarked for inclusion on Led Zeppelin II, this seven-and-a-half-minute marvel remains arguably rock music’s greatest drowsy seduction, Bonzo’s metronomic drums and John Paul Jones’ woozy jazz organ providing the backdrop as Page’s galactic soloing and Plant’s glass-shattering vocal build to what can only be described as a musical orgasm.

An electrifying comedown blues, Since I've Been Loving You also stands as a musical metaphor for the new decade, where the wide-eyed optimism of the ’60s would be traded for a far earthier reality.

4. When The Levee Breaks (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

The Led Zep version of When The Levee Breaks is one of the band’s authentic masterpieces of transforming acoustic country blues into monolithic rock. Words like ‘epic’ and ‘awesome’ have become drained and devalued by sheer repetition, but here they’re entirely justified. No heavy band ever played funkier, and no funk band ever played heavier.

Structurally, it’s one of the band’s simplest pieces: they jettisoned the original’s conventional 12-bar structure and played the song pretty much all on one chord, except for the serpentine riff which periodically inserts itself into proceedings. (They also retooled Joe McCoy’s original lyric, dropping some of his verses and adding new words of their own.) By contrast, it’s one of Jimmy Page’s most complex productions.

“You’ve got backwards harmonica, backwards echo, phasing, and there’s also flanging, and at the end you get this super-dense sound, in layers, that’s all built around the drum track,” explained Page. “And you’ve got Robert, constant in the middle, and everything starts to spiral around him. It’s all done with panning… each 12 bars has something new about it, though at first it might not be apparent. There’s a lot of different effects on there that at the time had never been used before. Phased vocals, a backwards echoed harmonica solo…”

Most important of all, the basic track was slowed down, giving it even more weight and murk. Lawdnose how many guitars Page overdubbed: layers of Mizzippi-mud Les Paul grunge, topped off with a clean, ringing slide guitar. It’s both huge and claustrophobic: Plant’s voice in perpetual danger of being overwhelmed by the immense natural forces swirling around him.

It also includes the most famous Zeppelin backbeat ever, and one that launched a thousand samples. As Robert Plant remarked: “John always felt his significance was minimal but if you take him off any of our tracks, it loses its potency and sex. I don’t think he really knew how important he was.”

3. Whole Lotta Love (Led Zeppelin II, 1969)

When Zeppelin faced the task of creating a follow-up to their mega successful debut, they blasted fans and critics alike with Led Zeppelin II, released in October 1969. This confident album topped the charts in the US and the UK, and sold three million copies within months. The opening salvo, Whole Lotta Love, rapidly became their new anthem. When played live, it caused a sensation and fans roared whenever Page set up that earth-shattering, blues-drenched riff.

The guitar, bass and drums heralded Robert Plant’s ear-shattering whoop and personal assessment that: 'Woman you need love!' This piece of rampant sexual chemistry was concocted at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London, and mixed later in New York; with the band constantly on the move, sessions had to be scheduled whenever tour dates permitted.

Plant opens his vocal section to Whole Lotta Love with a just-audible laugh and a yell of 'Baby, I’m not foolin’… I’m gonna give you my love!' Each of Robert’s love calls is greeted by a glissando from the guitar. Jimmy produced this particular effect by using a metal slide on the strings, as well as adding a backwards tape echo.

During the percussion interlude on this song, John Bonham stomps on his hi-hat and plays patterns on the bells of his ride cymbals, before unleashing an unwavering, battering assault on his snare drum. This innovative freak-out was largely cooked up by Page and Bonham alongside the band’s engineer, Eddie Kramer.

The track was edited down for US single release and got to number four in December 1969. Whole Lotta Love was a hit for Alexis Korner and his CCS big band, and became the long-running theme tune for the BBC’s Top Of The Pops programme.

2. Kashmir (Physical Graffiti, 1975)

A mood of sustained mystery and menace pervades what is undoubtedly one of Zeppelin’s greatest achievements. The impact of Kashmir was immediate when the tune made its debut on the blockbuster double-album Physical Graffiti in March 1975. The pulsating, hypnotic Eastern theme married to the insistent rhythm and orchestrated backing resulted in a most innovative piece of work. Yet, just as Stairway took time to grow in stature, so Kashmir was greeted with doubt and foreboding. It seemed to come out of nowhere.

The song was originally called Driving To Kashmir. Robert Plant had been on holiday in Morocco, a desert kingdom nowhere near Kashmir. Plant told how he had written the lyrics while driving through the Spanish Sahara. Apart from the occasional camel, there was nothing to see for miles and the single track, sandy road seemed to go on forever. Robert dreamed one day the road might lead to his own personal Shangri-La, in Kashmir.

Jimmy Page had devised the main part on a demo he’d made with John Bonham. It was based on a guitar tuning he’d used before on tunes like White Summer and Black Mountain Side. Combined with an arrangement by John Paul Jones, it was enhanced by Page’s use of Moorish-sounding chords played on a Danelectro guitar and backed by session string players. Peter Grant, their manager and mentor, thought the new song was “a dirge”.

It wasn’t like anything they’d ever written before, or anyone else for that matter. It was slow, ponderous and doomy, and flew in the face of contemporary trends in rock’n’roll. As an early example of music crossing over with world music, the band thought Kashmir was the highlight of their career. “It had all the elements that defined the band,” said John Paul Jones.

1. Stairway To Heaven (Led Zeppelin IV, 1971)

Anticipation was at fever pitch in 1971 as fans awaited the successor to Led Zeppelin III. This eclectic album, released the previous year, had dispelled the notion that Led Zeppelin were merely a heavy rock machine, incapable of playing anything more subtle than Whole Lotta Love. Ditties like Bron-Y-Aur Stomp and Hats Off To (Roy) Harper had veered the band into more folksy, acoustic areas. The untitled fourth album, eventually commonly known as Four Symbols, was just as fruitful, yet more consistent. It saw the unveiling of Stairway To Heaven; the band’s best known song, which was destined to become a rock classic.

Yet Stairway had humble beginnings. The first time the UK public heard it played live was in Belfast on 5 March, 1971. The ‘new number’ caught everyone by surprise. ‘What’s this?’ they cried, as what seemed like a Led Zeppelin symphony began to unfold. It soon became clear that Stairway was a perfectly formed piece of music, full of contrast and dramatic devices. In the best classical tradition, every step on the musical ladder helped progress the arrangement.

There was the famed acoustic guitar intro, John Bonham’s brutal drum entry, Robert Plant’s passionate vocals and Pagey’s full-blown guitar solo. Another important facet was John Paul Jones’ warbling wooden recorders – heard on the album, but alas never made it on stage.

It all contributed to a masterpiece that simply gripped the public’s imagination. In fact, Jimmy Page’s double-necked guitar melody became so popular with aspiring players, it was banned from being played in guitar shops. Stairway To Heaven was assembled by trial and error during sessions at Headley Grange, in Hampshire, with the aid of the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio. The old mansion was ramshackled, neglected and supposedly haunted – but the former Victorian workhouse had great acoustics. It was so cold in the bleak midwinter of 1970 that the band were forced to burn the stairway’s banisters to keep warm.

As a result, Robert wrote the lyrics while sat on a stool in front of the blazing fire. Page had already recorded his ideas for the main theme on cassette tapes he brought to the manor for Plant to hear. A rehearsal tape of Stairway helped everyone focus on the lyrics. The crucial moment when Bonham picked up the beat was a device Jimmy had used before. He explained: “I wanted to create that extra kick. There’s a fanfare near the guitar solo, then Robert comes in with his tremendous vocal.

Stairway crystallised the essence of the band. It had everything there and showed the band at its best. It was such a milestone for us.” After work was completed at Headley Grange, the bulk of the eight-minute piece, including Jimmy’s Fender Telecaster solo, was recorded at Island Studios in London, which had better facilities. John Paul Jones added Hohner electric piano and bass guitar, while Jimmy delivered the final guitar overdubs. Said engineer Andy Johns: “I knew Stairway was going to be a monster. But I didn’t know it would become a bloody anthem!”

Indeed, it became ‘the most played track’ on US radio and won copious awards. However, Robert was embarrassed about its sentiments and such lines as: 'There’s a lady who’s sure all that glitters is gold/And she’s buying a stairway to heaven.' After the demise of Led Zeppelin following John Bonham’s death in 1980, Jimmy Page performed it as an instrumental, when he made his comeback at a concert at the Royal Albert Hall in 1982.

It’s been both loved and loathed in equal measures, but nowhere is Page’s supreme understanding of rock dynamics better illustrated than on Stairway, with a song that teases and caresses and then climaxes with nothing less than the world’s greatest ever guitar solo.

All that glitters is not gold. But this is. This is what we came here for.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Paul Moody is a writer whose work has appeared in the Classic Rock, NME, Time Out, Uncut, Arena and the Guardian. He is the co-author of The Search for the Perfect Pub and The Rough Pub Guide.

- Fraser LewryOnline Editor, Classic Rock

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.