Fantastically flash, inscrutably cool: How the Yardbirds shaped rock'n'roll

They had Eric Clapton. They had Jeff Beck. They had Jimmy Page. In the late 60s, no other band could get close to them. And without The Yardbirds, there would be no Led Zeppelin

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Saturday night in New York: March 30, 1968 – the summer of hate almost upon us. Five nights later Martin Luther King Jr. will be shot and killed in Memphis. Two months later Bobby Kennedy will be similarly assassinated. By the end of the year Richard Milhous Nixon will be elected 37th President of the United States.

The Beatles’ Hey Jude may be the biggest-selling single of the year, but it’s the record’s B-side, Revolution, that speaks loudest to the generation of longhairs and acid trippers lining up outside the Anderson Theatre on 66 Second Avenue on this cold spring night, here to see The Yardbirds – Britain’s grooviest band. Or what’s left of them. Three dates into their eighth US tour in four years, although guitarist Jimmy Page and bassist Chris Dreja don’t know it yet, this will be the last tour the band ever do.

“We lost enthusiasm for it,” drummer and co-founder Jim McCarty says now. “We just didn’t have the energy for it. If we’d had a long break and sat down and had a rest and taken time to think of new songs, it might have been an idea. But everything back then was based on working, playing every night.” He sighs. “They thought if you had six months off no one would recognise you any more.”

Nevertheless, it seemed a strange time to call a halt to what had been one of the most inventive, famous and influential bands of the Swinging Sixties. The world may have been going to hell – aka Vietnam’s Mekong Delta – but rock music was fast approaching its apotheosis. When serious music fans weren’t out on a Magical Mystery Tour in chase of an under-dressed Mrs Robinson, they were tripping in a White Room listening to Janis screaming for them to take another Piece Of My Heart, or leaning over wide-eyed at innocent passers-by telling them Hello, I Love You, while all the while two riders were approaching…

The Yardbirds – famous for proto-psych hits like For Your Love, Shapes Of Things and Over, Upwards, Sideways, Down – had also been home to the three best guitarists in England: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and, now, Jimmy Page. Had appeared in seminal art-house flicks like Antonio’s Blow-Up. Were worshipped by up-and-comers like David Bowie, Rod Stewart, Steven Tyler, Alice Cooper, Lemmy, Gary Moore, Alex Lifeson… The Yardbirds were walking, talking history – even by 1968.

But instead of sticking around for the transformation into album artists that would transform contemporaries such as The Who, The Kinks, Cream and the Stones into global superstars in the late-60s, The Yardbirds were about to throw in the towel. Why?

The trouble, says McCarty, was: “We were desperate. We didn’t want to do another Yardbirds tour.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He and singer Keith Relf had been talking privately about splitting for months.

“We wanted a change – to do some other kinds of songs, some different music. Something refreshing. After playing that heavy stuff night after night, in the end it wasn’t going anywhere… But they wanted to carry on.”

‘They’ were Dreja and Page. And yes they bloody well did want to carry on.

Or Jimmy Page did, anyway.

It was a real sliding doors moment that night at the Anderson Theatre. You only have to listen to the live recording of the show – now immortalised for the first time officially on the just-released Yardbirds ’68 album (produced and digitally remastered by Page, and now available on various formats through his official website) – to grasp what might have been had McCarty and Relf not wanted out so badly.

It’s not overstating the case to describe this as proto-Led Zeppelin. And no shame in wondering what this band would have achieved had Page not left just three months later to find a new singer and rhythm section to play with – in what was originally announced at the time as being The Yardbirds Featuring Jimmy Page, then just weeks later the New Yardbirds. Then, even more suddenly, spookily, a whole new other thing – supposedly – called Led Zeppelin.

In fact, listening to the live ’68 album, ‘the New Yardbirds’ really would have been a more accurate description of the outfit Page pulled together in the months that followed that Anderson Theatre show. Because, it’s all right there in New York in March 1968. Not just the sonic templates of Train Kept A-Rolling, Dazed And Confused and White Summer – but also in the whole smart-arse, ‘don’t try this at home, we are your overlords’ vibe.

The Yardbirds had always been fantastically flash, inscrutably cool, fabulously out of reach. Their early shows were self-described as ‘rave-ups’ – wild, hair-down, knickers-off parties for the wilfully far out, the fashionably fuck you. They weren’t dirty rockers, but they were photographed riding Harleys. They weren’t poncey mods but they dressed to the nines, part King’s Road, part Haight-Ashbury.

“You couldn’t touch them,” Lemmy would tell me years later. “Especially the line-up with Jeff Beck in it. It was the same feeling I got when I later saw the MC5 – they just attacked you, went for the jugular. When Page joined it became a bit more experimental but it was still the same sort of vibe – very daring. I always liked that.”

Indeed the musical journey The Yardbirds undertook in their short but adventure-filled five years together went through so many twists and turns that their career seemed to nutshell the melting-pot atmosphere of the 60s as clearly as did that of The Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

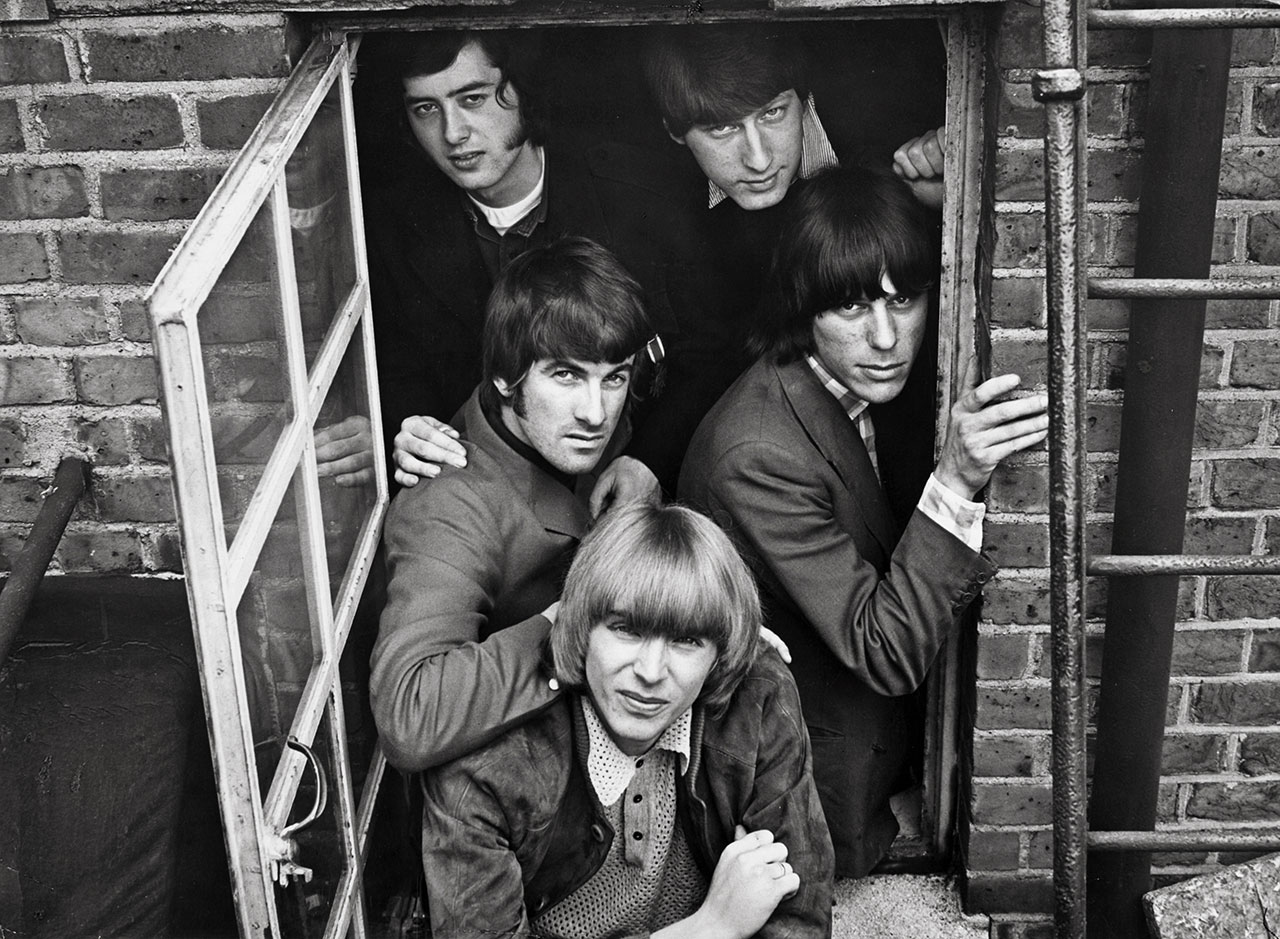

They formed in May 1963 around the creative nucleus of 20-year-olds Keith Relf (blond, singer, harmonica player, lyric writer and screamy-teen pin-up), and Paul Samwell-Smith (dark-haired bassist, guitarist, keyboard player, vocalist, percussionist, producer and all-round leading light). As members of the Metropolitan Blues Quartet they had played on the same jazz-blues circuit as the Stones. Before teaming up with 20-year-old Jim McCarty (drummer, vocalist, guitarist) and two other schoolboy pals –18-year-old Chris Dreja (guitar, bass, keyboards) and 15-year-old Anthony ‘Top’ Topham – the band’s first lead guitarist.

Taking their name from seminal jazz-junkie dead-legend Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker, the started out playing covers: Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Bo Diddley, Elmore James – strictly high-quality underground purist R&B.

Which is how they hooked up with Eric Clapton, an 18-year-old blues disciple who’d recently been in The Roosters, a short-lived R&B band. When Top bailed to get a proper job, Clapton took his place.

By then The Yardbirds had replaced the Stones as the house band at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, and owner Giorgio Gomelsky had become their manager. Gomelsky was a typical 60s mover-and-shaker, ran clubs, wrote songs, made films, produced records… Whatever you needed, Giorgio could get it. Fast.

For the next 18 months The Yardbirds toured as the backing band for Sonny Boy Williamson II. Giorgio had the foresight to record some of the shows, and released them two years later, at the height of Yardbirds-mania, as the album Sonny Boy Williamson And The Yardbirds. In the meantime he landed the band a deal in their own right with EMI.

Not that the album sold. In fact nothing The Yardbirds did sold during the early Clapton days. And certainly not their debut album, Five Live Yardbirds, an R&B purist’s delight released into the commercial abyss at the end of 1964.

Enter Giorgio with an even better idea: a song so obviously a hit-in-waiting that its publisher, Ronnie Beck of Feldman’s, was on his way to try to convince The Beatles to record it when Giorgio stepped in and grabbed it first.

Written by 19-year-old future 10cc star Graham Gouldman, For Your Love was both the making of The Yardbirds and the breaking of Eric Clapton, who called it “pop crap”. Led off by Brian Auger on harpsichord, the recording was made by Relf and McCarty along with session musicians on bass and bongos, and Samwell-Smith in the control room ‘directing’.

Clapton and Dreja were called in only for the freak-out mid-section. But even that was too much for Eric, and he bailed straight afterwards to join John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. In an age of art for art’s sake, hit singles for fuck sake, blues-precious Clapton just didn’t fit in. Not even when the single hit the Top 10 in both Britain and America.

His replacement, a 21-year-old maverick called Jeff Beck, would be no pushover either. “I didn’t like them when I first met them,” Beck said. “They didn’t say hi or anything. They were pissed off that Eric had left; they had thought that the whole Yardbirds sound had gone.”

Unlike Clapton, though, Beck craved the spotlight in a way that would shame a firefly. “I wanted people to look at me, know what I was doing,” he would say. “I’m not one of those guys who wants to fade into the background on stage.”

There was never any danger of that as the next 12 months found Beck leading The Yardbirds through hit after hit, each more rule-bending than the last.

This, though, had sprung from another sliding-doors moment in the career of The Yardbirds. For Beck had not been the band’s first choice as Clapton’s replacement. That had been Jimmy Page, at the time the most accomplished and versatile guitarist in Britain, with hard-won experience and musical nous far superior to that of either Clapton or Beck.

But Page turned them down. Not because he was a blues purist or had a problem with the idea of performing hits, but because he was out of their league. By 1964, Page had already played as a session guitarist on dozens of UK chart hits for dozens of artists including Shirley Bassey (Goldfinger), the Nashville Teens (Tobacco Road), Dave Berry (The Crying Game) and Them (Baby, Please Don’t Go), and countless others for The Kinks, The Who, Herman’s Hermits, Lulu, on and on, for years to come. Hey, when you’ve played on mega-hits, who cares about one-hit wonders like The Yardbirds?

But Page did know someone who might care: his friend and fellow guitarist Jeff Beck. Beck was one of those cats on the fringes, partly by choice. A brilliant soloist, he was an individualist, and his stints in various R&B bands of the period – The Nightshift, The Rumble, The Tridents – were built for speed not comfort.

Beck was “sitting around doing nothing” when one day at Page’s house, Jimmy played him Five Live Yardbirds, then asked what he thought. Jeff thought he needed a gig. And with Jimmy offering to recommend him, he was in the studio three weeks later recording the next Yardbirds single, another Graham Gouldman song – and obvious hit-in-the-making – Heart Full Of Soul.

For the next couple of years The Yardbirds, with Beck on lead guitar, were at the peak of their powers, commercially, artistically, pop- and rock-tastically. They had a string of major hit singles in Britain and America – all Gouldman-written or blues covers, until they came to their seventh single, Shapes Of Things, credited to McCarty, Relf and Samwell-Smith. It reached No.3 in the UK in March 1966 and soon after that the Top 10 in the US.

With its marching-army-of-robots rhythm, its feedback-laden guitar solo, its tang of the Asiatic, Shapes Of Things was the most exotic-sounding single of the year. So much so that music historians now cite it as possibly the first truly psychedelic record.

But Beck did not share in the writing credits, and this appeared to only increase his already chafed relationship with the rest of the band.

“He was always a lovely guy, Jeff,” says McCarty, “and I used to really like him. But when it came to playing he was different. You never really knew what was going to happen. You never really knew what sort of mood he was going to be in. And that depended a lot on what sort of sound he got on stage. If he got a good sound on stage he’d be quite happy and it would be a happy gig. But the reverse was that he’d get very angry.”

To the point where it would sabotage shows?

“It could do. He could kick an amp off stage or kick an amp over or he could walk off. He usually did the whole gig. He didn’t disappear. But he walked off one time on one TV show we were doing. He didn’t like the mix of his guitar, it was too quiet. And we were just miming.”

It was Samwell-Smith, though, who was the first to leave, after they played a drunken gig at the annual May Ball at Queens College in Oxford, which turned into a near-brawl between Relf and some of the students. Outraged, Smith stormed off, he said, never to return. (Although he was back as producer shortly after.)

With a new album, Yardbirds, aka Roger The Engineer, out to promote, and panicking about how they were going to continue their never-ending touring schedule, Jimmy Page, who was there, half-jokingly said: “I’ll do it.” Then happily ‘allowed’ the others to talk him into it. In fact Page, by then suffocating on the session scene, had watched with increasing envy the success of The Yardbirds with his old pal Beck as their career took off around the world. It wasn’t about the money – he still earned more in a week than most bands like The Yardbirds did in a month – it was the thought of making his own music, for once.

“I want to contribute a great deal more to The Yardbirds than just standing there looking glum,’’ Page told the NME at the time. “I was drying up as a guitarist. I was playing a lot of rhythm guitar on sessions, which is very dull. It left me no time to practise. Most of the musicians I know think I have done the right thing in joining The Yardbirds.”

Three nights later, Page made his debut with The Yardbirds – on bass – at the Marquee in London. His first recording with them was at the Marquee studios the following day for a Yardley Great Shakes advert (‘It’s so creamy/Thick and dreamy’) that was based on their current UK hit Over Under Sideways Down. That was followed with 24 more British dates in such salubrious locales as the Co-Op Ballroom in Gravesend and the Pavilion Arts Centre in Buxton.

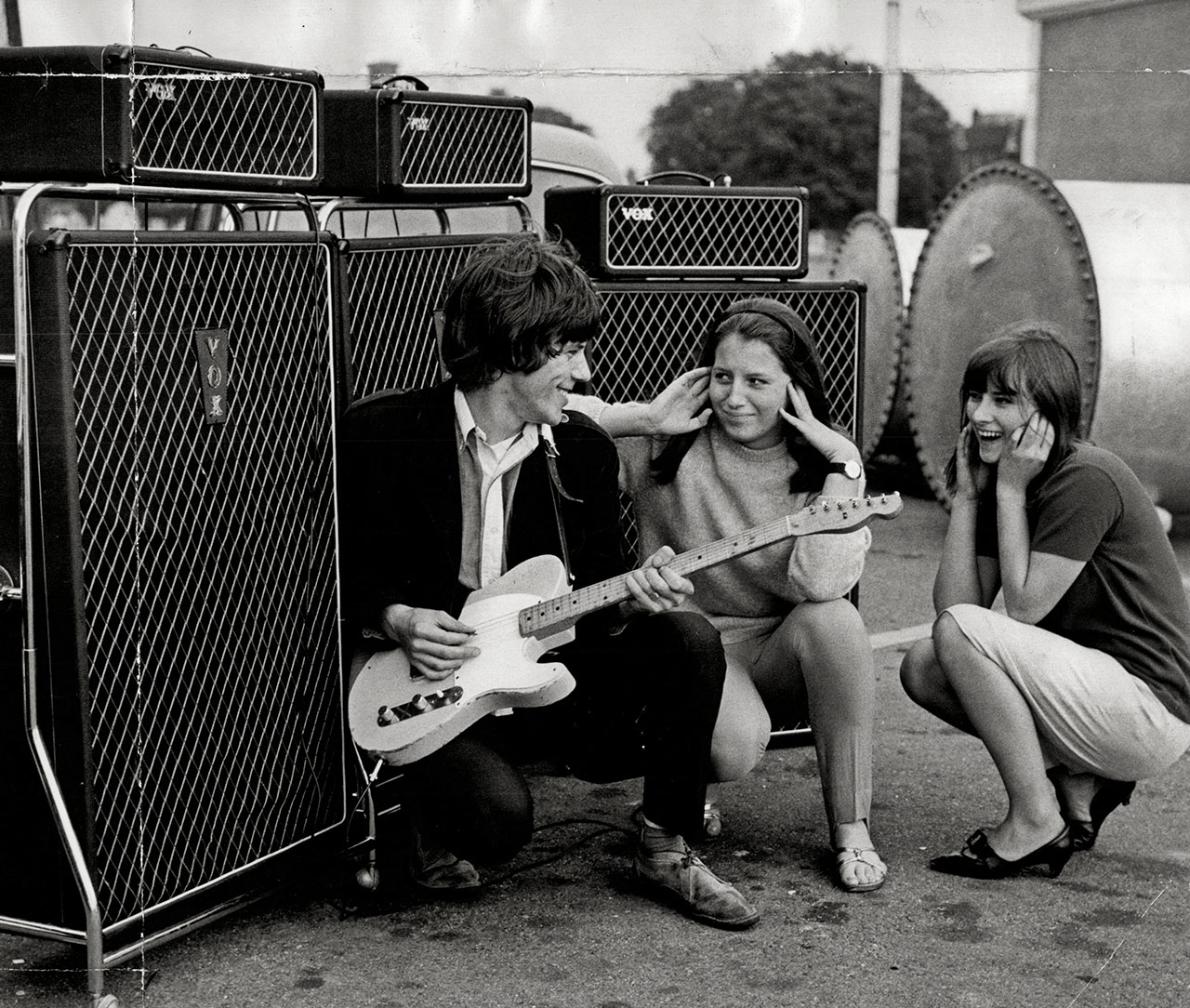

Then, on Friday August 5, 1966, Page played his first show in America with the band, at the Minneapolis Auditorium. By now Chris Dreja had been moved over on to the bass, making way for Page to take over guitar, forming with Beck what would be the first ‘twin-solo’ guitar line-up in British rock. It should have made The Yardbirds the most incendiary group on the planet – not just weighty like Cream, or laddish like the Stones, and certainly more nail-biting than The Beatles, who would retire from touring just three weeks later.

“It definitely gave the band a kick up the arse,” says Chris Dreja now, who also says he wasn’t put out when Page took his place as guitarist. “Not at all. No, no. I’m a man who knows his own limitations,” he says. Then jokingly suggests that Page wasn’t moved up from bass to guitar because he was the better guitarist, but because Page was such a bad bass player. “As a bass player he was rubbish. Too many bloody notes, mate!”

Having been the ‘other guitarist’ to Clapton, Beck and Page, who did he rate as the best?

“I enjoyed playing with all of them. They all came with such individual characteristics. Eric was a blues man. With Jeff you never knew what he was coming up with. He was a bloody genius, wasn’t he? But I loved to play with Jimmy. He was full of energy. Go go go! And I liked that. He was very positive. Still is today. He’s a wonderful man.”

Dreja and Page revelled in life on the road in America – “Americans bands and musicians were so creative, such really great people to get to know,” says Dreja. “So many stories… being in a basement with Janis Joplin drinking Southern Comfort, things like that… All the wonderful people you met on the road, you became almost like one big family.”

Keith Relf, however, was feeling the slog. Disillusioned, disgruntled and often drunk, Relf would later claim that the best days of The Yardbirds had been when Eric was still in it; before For Your Love – and in its wake the arrival of Jeff. “The happiest times were playing London clubs like the Marquee and the Crawdaddy Club,” he said in 1974. “With Eric it was a blues band.” After that, “it became a commercial band. We started touring the States, doing Dick Clark tours, playing one-nighters and that kind of thing.”

But at least Relf kept going. Beck now suddenly decided he wanted to stop completely.

“It was being on the road that got to Jeff,” claimed Relf. “He didn’t want to go out any more. We stayed in Hollywood for a bit… it’s a bit of a painful period to go over. It was during a Dick Clark tour, all right, which is heavy enough anyway. We had a few days off and Jeff fell in love with Hollywood. We went out on the road, and by the second day Jeff had had enough. So he flew back to Hollywood. And henceforth the final stage of The Yardbirds.”

To be more accurate, Beck had fallen in love with a Hollywood actress called Mary Hughes. “It was over Mary that he left The Yardbirds,” Relf admitted with a shrug. A 22-year-old blonde beauty who had been ‘discovered’ on the beach in Malibu, Hughes had starred in a handful of ‘bikini’ movies like Muscle Beach Party (1964) and drive-in B-reels like Fireball (1966). She would also star alongside Elvis Presley in Thunder Alley (1967). None of these were Oscar-material. But Mary’s looks were pure platinum, and Beck fell for her hard. (So hard he wrote a song for her, Psycho Daisies, and sang the lead when it was a Yardbirds B-side.)

Refusing to leave LA, Beck stayed behind with Hughes while the rest of the band soldiered on as a four-piece. A press release was issued explaining that Beck was “ill”.

In an oblique reference to that incident in an early-70s interview with Rolling Stone, Beck explained: “I really wanted Jim Page on lead guitar with me because I knew it would sound sensational. We had fun. I remember doing some really nice jobs with Page. It lasted about four or five months, then I had this throat thing come on, inflamed tonsils, and what with inflamed brain, inflamed tonsils and an inflamed cock and everything else…”

Beck returned to the band for a September ’66 tour in Britain opening for the Stones, but the writing was on the wall. His final bow with them came with his now legendary appearance with the band in the 1967 film Blow-Up. Italian producer Michelangelo Antonioni had tried unsuccessfully to get The Who for the scene, then the more psychedelic Tomorrow – although how their guitarist, future Yes star Steve Howe would have handled the guitar-smashing segment in the film is anybody’s guess.

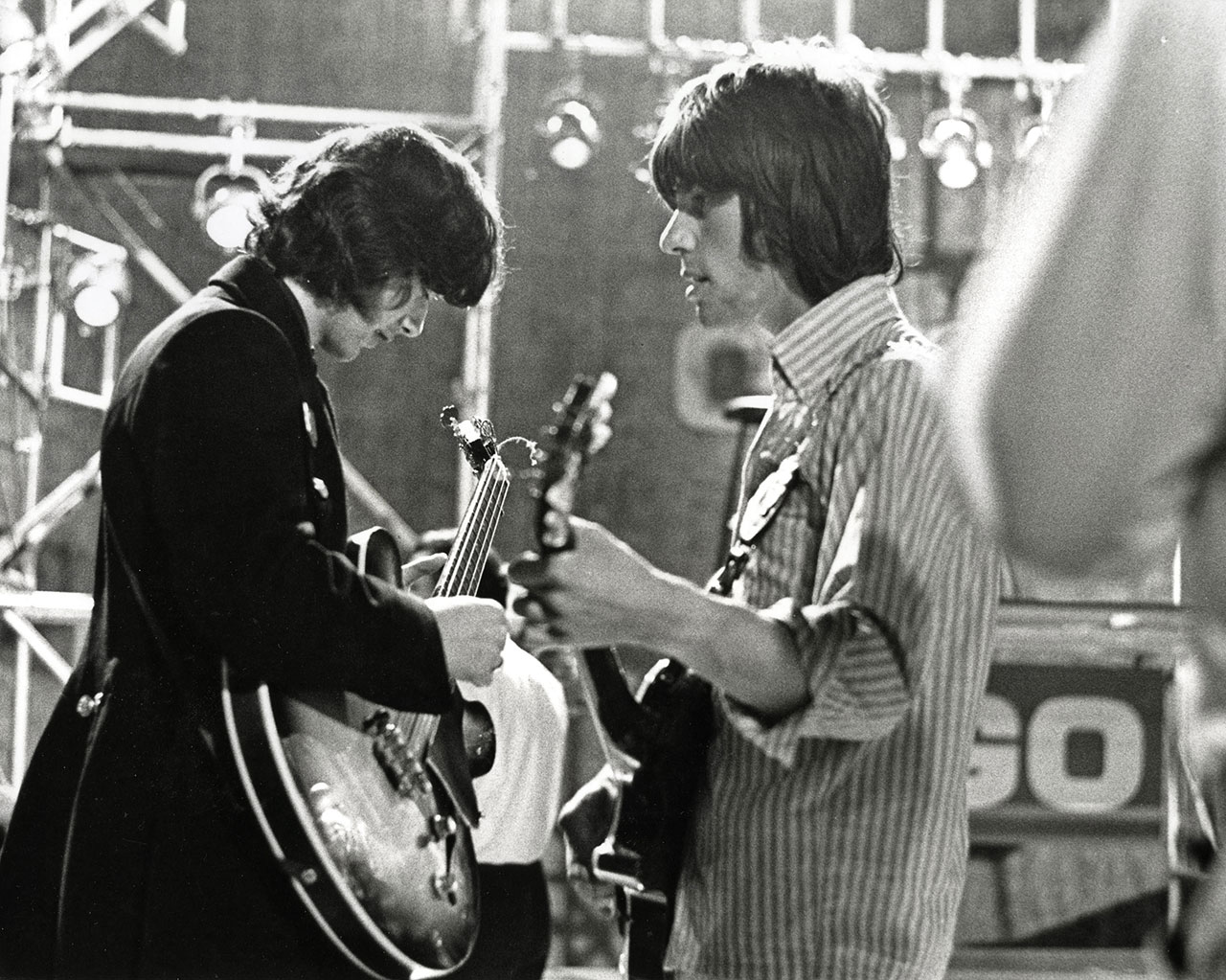

Although both McCarty and Dreja chuckle heartily now over their appearance in what is now remembered as one of the late 60s’ most preposterous and self-consciously impenetrable ‘underground films’, watching them plough through Stroll On in the film today is instructive of the way The Yardbirds with Beck and Page in it really were. Beck: solemn, threatening; Page: smiley, cool, noooo problem.

Beck of course hated being the one to “do a Townshend”, as he put it, in the film and smash his guitar. “I didn’t mind playing a very wild number with lots of violence in it, lots of chords smashing away, but I didn’t actually want to destroy the guitar. What a cheat: the first part shows me playing a Les Paul, and in the second part I’m smashing up a cheap old thity-five-dollar Japanese model.”

Go to YouTube though and find one of their real live shows together and the overwhelming impression is of a band almost tripping over its own astonishing power. Not the musicianship, but those two huge personalities.

McCarty laughs. “I know! It was like the group was bursting out. It could hardly be contained. It was a very good combination with them both. I asked Jimmy the other day, actually: ‘Did you enjoy it with Jeff? ‘He said: ‘Oh yes, yeah!’ But actually it was a bit much sometimes.”

Dreja agrees. “Yeah, a lot of the time it was fantastic, and a lot of the time they’d be playing against each other. It was a bit of a cacophony sometimes. They were quite competitive. Jeff would inevitably suffer, because he was more insecure. But now and then it would work and it would be fantastic.”

McCarty recalls the Beck-Page axis at its best one night outgunning the Stones: “I remember when we were on a tour with the Stones. We had a fantastic evening and the audience was delighted. And that was quite embarrassing for the Stones.”

Sadly, the only real recordings this line-up of The Yardbirds got to make were the aforementioned Stroll On, their barely veiled ‘reworking’ of Tiny Bradshaw’s Train Kept A-Rollin (basically a slightly different lyric written by Relf), done specifically for the Blow-Up soundtrack album, and one other that clearly signposted exactly where Jimmy Page intended to go next in his career – with or without The Yardbirds. It was called Happenings Ten Years Time Ago and it was a monumental piece of work. Released as a single in October 1966, months before first albums by Cream, Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd, at a time when The Beatles were topping the charts with Yellow Submarine, this was more than simple pop psychedelia. This was ground-zero 70s rock.

Hypnotically interweaving Eastern-influenced guitars, weapons-grade rhythms (with not Dreja on bass, but a top session pal of Jimmy’s called John Paul Jones), ghostly vocals singing of time-travel, tripping on déjà vu and occult meaning, whispered backing vocals (‘Pop group are ya? Why you all got long hair?’). If you’re looking for the real rock roots of Led Zeppelin and every other out-there band that came helter-skelter in their wake, this is the definitive place to start.

And yet as a single it flopped: tiptoeing to No.30 in America, and brushing shoulders only briefly with the Top 40 in the UK – this despite an appearance on Top Of The Pops, taped on October 19.

“I thought it could have been commercial,” says Jim McCarty. “But we sort of thought, well, we’ll go no-holds-barred on that, really. Try and do something a bit different. Which is what we’d always done.”

There is, however, one other significant recording Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page had made together that summer of ’66. Before being offered the chance to join The Yardbirds, Page had been working towards putting his own band together. His initial idea was to lure Small Faces singer/guitarist Steve Marriott into a new outfit, or possibly Spencer Davis Group protégé Steve Winwood on vocals and keyboards, along with what Page now calls a “super-hooligan” rhythm section nicked from The Who: Keith Moon on drums and John Entwistle on bass.

That had been in May, when Page had overseen the session at London’s IBC studios that would produce the track Beck’s Bolero – Jeff Beck’s guitar-enflamed version of Ravel’s Bolero originally intended to be his first solo single, and that Page would later insist he arranged, played on and produced.

“Jeff was playing and I was sort of in the [control booth]. And even though he said he wrote it, I wrote it. I’m playing all the electric and twelve-string, but it was supposed to be a solo record for him. The slide bits are his, and I’m just basically playing.”

That, however, is something that Beck flatly refutes. “No, [Jimmy] didn’t write that song. We sat down in his front room once, a little, tiny, pokey room, and he was sitting on the arm of a chair and he started playing that Ravel rhythm. He had a twelve-string and it sounded so full, really fat and heavy. I just played the melody. And I went home and worked out [the up-tempo section].”

In the end it hardly mattered. Producer Mickie Most – the Simon Cowell of his day; hits first, nothing else second – who would oversee Beck’s later solo career, would eventually release it only as the B-side of Beck’s single Hi Ho Silver Lining. Still, the guitarists continued to argue over who did what. The only thing they did later agree on is that line-up that played on Beck’s Bolero could have been the “original” Led Zeppelin.

Also on the session that night was John Paul Jones, who weeks later would be brought in, at Page’s insistence, to play on The Yardbirds’ Happenings Ten Years Time Ago. Later Jones arranged the strings on the Yardbirds track Little Games and played bass on their next single, Ten Little Indians.

The biggest presence at the Bolero session, though, was that of Keith Moon, who’d arrived at the studios in Langham Place wearing shades and a Cossack hat in case anybody saw and recognised him. Moon was at the time pissed off at The Who, fed up with Daltrey’s constant fighting and Townshend’s black moods. John Entwistle, who had also promised to turn up but backed out at the last minute, felt the same, Keith said, and both were looking for a way out of the grind of being the background to the Pete and Rog show.

Sensing an opportunity, Page laughingly suggested they all team up together: Keith and Jimmy and John and Jeff. (No mention of Jones, at this stage.) Moon got all excited and even accidentally suggested a name for the new line-up when he joked that it would go down like a lead zeppelin, meaning balloon. (Entwistle would later swear blind it was he who had suggested the name, but it was Moon that Page would later ask for his blessing to use the name.) Everyone had laughed at Keith, smoking cigarettes and speeding out of his head. But Jimmy had liked the idea – and the name – and tucked it away in his back pocket, like he had done a lot of good ideas over the past four years working in studios with frustrated musos. Half-Yardbirds, half-Who, pushed in the right direction by boss man Page.

All they would need was a good singer. Moony had said Entwistle could sing, but Jimmy was thinking more of Steve Winwood. Then Traffic started taking off big-time, so he thought of Marriott instead. Page knew Marriott well, knew he was up for anything. In fact the more he thought about it, the more he liked the idea: Jimmy, Jeff, Moony and Entwistle, with Stevie Marriott up front… What a supergroup that would be! Or as he later recalled: “It would have been the first of all those sort of bands, like Cream sort of thing.”

Not surprisingly, the success of the Bolero session had given Beck similar ideas, like two mates out for the night spotting and fancying the same girl. Keith Moon, he said, “had the most vicious drum sound and the wildest personality. At that point he wasn’t turning up for Who sessions, so I thought that with a little wheeling and dealing I could sneak him away.”

To what, though? At that stage the Jeff Beck Group was still more wishful thinking than reality, and there was his old pal Page, in the control booth, overseeing everything. Not that Beck didn’t cotton on to all that. As he said: “That was probably the first Led Zeppelin band. Not with that name, but that kind of thing.” Moony, he said “was the only hooligan who could play properly. I thought: ‘This is it!’ You could feel the excitement, not knowing what you were going to play, but just whoosh! It was great and there were all these things going on, but nothing really happened afterwards because Moony couldn’t leave The Who.”

That fact alone wasn’t enough to deter Jimmy Page, and despite joining The Yardbirds just weeks later, behind the scenes he still put feelers out to see if Marriott might be interested in leaving the Small Faces to join forces with him in some new unspecified group project. “He was approached,” Page would later reveal, “and seemed to be full of glee about it. A message came from the business side of Marriott, though, which said: ‘How would you like to play guitar with broken fingers?’”

The “business side” of Marriott was Don Arden, the self-proclaimed “Al Capone of pop” and then the most notoriously gangster-like figure in the British music business.

When I asked Arden about this myself, before he succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease in 2007, he smiled menacingly and said: “Later on I’d hang fucking [music entrepreneur] Robert Stigwood over a balcony for daring to try and take Stevie Marriott away from me. You think I’d let some little schlemiel from The Yardbirds have him?”

After that, said Page, “the idea sort of fell apart. We just said: ‘Let’s forget about the whole thing, quick.’ Instead of being more positive about it and looking for another singer, we just let it slip by. Then The Who began a tour, The Yardbirds began a tour and that was it.”

The idea might have been gone for now, but it was not to be forgotten. Not by Page, anyway.

Back on tour in America as part of the Dick Clark Caravan Of Stars – sharing the bill with such luminaries as Sam The Sham & The Pharaohs, Brian Hyland and Gary Lewis & The Playboys – Jeff Beck finally broke down and left the band. Weeks of on-tour aggro – late-shows, tantrums, freak-outs – finally coalesced into what he later described as a full-on nervous breakdown.

“I don’t know if you know what a nervous breakdown really is, but I had one,” he told Rolling Stone in 1971. “I had fainted and fell down about three flights of stone stairs, couldn’t even speak to the doctor, and after he gives me about three thousand prescriptions he tells me I’ll be alright, I just have meningitis. And I thought: ‘My mother told me meningitis was a bad disease…’”

The official announcement of Beck’s departure – and of The Yardbirds continuing as a four-piece with just Page on guitar – came just a few weeks later. Meanwhile, the band ploughed on without a break through Christmas and New Year through dozens more US shows, followed by dates in Australia Singapore, New Zealand, France… and back to Britain, America… on and on.

They were still on tour in July 1967 when Little Games, their only album with Page, was released. Recorded on the fly in March and April that year, and with Page credited as co-songwriter of six of the album’s seven original songs, it’s impossible to listen to it today and see it as anything other than a pre-Zeppelin Led Zeppelin album.

The future was being written on tracks like Smile On Me, it’s heavy gas blues steamrollering along, Page’s scab-picking guitar break there to be reopened on You Shook Me on the first Zeppelin album. Similarly, the raging guitar intro to Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Sailor, credited on Little Games to Page and McCarty (the latter recalls writing the track at Jimmy’s Epsom home), would again be revisited: you can hear it reborn in the ringing symphonic guitars of the Zeppelin track The Song Remains The Same – part sonic overture, part hippie dream, layered to such extremes that it begins to resemble the sound of a sitar or tambura, Robert Plant’s artificially accelerated vocals in such a high register they too begin to resemble the excitement of Indian reed and vocal music.

Tinker also featured the sound of Page playing his guitar – a Vox 12-string in this case – with a violin bow. It was a technique he would also employ on another of Litte Games’s cornerstone tracks, Glimpses. This was the closest Page felt he really got to where he wanted to go after Beck left The Yardbirds. By the time the album came out, Glimpses was already a live show-stopper. Some saw Page sawing away at his Telecaster (unlike the Gibson Les Paul he would use more in Zeppelin) as a gimmick, but using a bow on the guitar was more than just a novelty for a musician of Page’s stature.

On stage he would use homemade tapes of various sound effects, which he would play along with, improvising to the sound of the Staten Island Ferry, full of crunching noises and horns, random voices, poetry… He had wanted to have some Hitler speeches on the tapes too, but the others said that would be going too far. But Page was still just 22, and the concept of ‘too far’ was unknown to him.

On tour once again in America, however, the band were now beginning to play in newly opened underground venues like Fillmore East. Making the sky fall during Glimpses was where it was at, where it could be, where it should be going. Page even talked about using tape recorders that were triggered by light beams, with a go-go dancer doing her thing, making the lights flash and the music take off… and everyone would look at him as though he was mad.

The Yardbirds were now a long way away from the world of For Your Love. So much so that Keith Relf’s own solo spot on the album, his gentle and wintery Only The Black Rose sounds solitary and out of place.

Then there was White Summer, an acoustic guitar instrumental in the exotic, modal style of Page’s later Zeppelin showcase track Black Mountain Side, down to the percussive accompaniment of tablas, the Indian hand drums, played on this occasion by Chris Karan. This was Page’s interpretation of folk maverick Davy Graham’s famous version of She Moved Through The Fair (or, more accurately, Graham’s own later reinterpretation of the song as She Moved Through The Bizarre/Blue Ragga), with its unique D-A-D-G-A-D tuning – a signature Graham tuning he had devised for playing Moroccan music, that also proved especially efficacious for the accompaniment of ancient modal Irish tunes.

“I was going to add on the sitar part,” Page later he told Vibrations magazine. “But when I got down to the studio the following day the producer had sort of reduced the whole thing. I can assure you in the future we will take longer ,because we are so despondent about the whole thing.”

The producer in question, Mickie Most, was in fact utterly disdainful of Page’s attempts to draw The Yardbirds out of their pop chart comfort zone and into… something else.

“There had been some pretty substantial work done by Jeff there in The Yardbirds, some fabulous stuff,” Page recalled in 2014. “But I really needed to make my own sort of statement. So I was starting to showcase some of the various areas that I’d been involved with in my own learning curve – all the different styles and everything. I saw that that was the right way to go.”

He would find a stronger ally in the new tour manager Most had hired for the band, a guy called Peter Grant.

Grant, the most feared figure in the Led Zeppelin story – his reputation for ‘protecting’ his artists, learned at the knee of Don Arden – is someone Chris Dreja now describes as “a wonderful guy. A lovely human being.”

He recalls how in The Yardbirds, “Peter was very hands-on. He worked in an office with Mickie Most. They had two desks opposite each other. And he came on the road. It was amazing. He came on all the tours with us. Held it all together. He taught me how to make money – not have too much room service, all these little things. I loved the guy. We spent time at his house. He played me the first cut of Stairway To Heaven, with a few mistakes in it by Jimmy. Which he obviously corrected later.

“Peter was a wonderful guy. He was very kind to me. He loved his artists. I know he could be a real bastard in real life with other people, but as far as the artists were concerned he really had a rapport with them.”

He certainly did. Especially with the band’s go-go-go guitarist, Jimmy Page.

When Little Games failed dismally in the charts, it was the end of the road for Keith Relf and Jim McCarty. Unlike Page, who had yet to climb the mountain, in terms of his own creativity, Relf and McCarty now felt they had been there, done that, worn out the T-shirt. The thought of following Page on some new musical odyssey was simply too much wishful thinking for them. Having been in a band that had sacrificed so much to reach the top of the singles charts, the idea of somehow reversing gear and from now on concentrating instead on albums, on yet more live shows, on lengthier and more demanding tours than ever before, simply did not go down well.

By the time they arrived in New York for their Anderson Theatre show on March 30, 1968, Relf and McCarty had already made up their minds. And so had Page and Dreja.

There was a final Yardbirds single, the aptly titled Goodnight Sweet Josephine. It was another big flop. Although on its B-side lay the future: the Relf-Page-McCarty-credited Think About It, replete with a frantically shredded Page solo that would later turn up, almost intact, as the guitar solo of another number the band had recently begun playing live called Dazed And Confused. Page firing from the hip on his Telecaster, having stripped the blonde paint off and hand-painted a green, red and orange psychedelic dragon on the front of its ash body.

You can hear it in all its vivid glory on the Yardbirds ’68 album – a fact which Page must be given enormous credit for, demonstrating that the track which he would be given sole credit for on the first Led Zeppelin album, and which became his live showcase throughout all of Zeppelin’s best moments on stage, was actually another important piece of the jigsaw originally begun, in embryonic form, during his stint as the creative driver of The Yardbirds.

It was based on a song by the same name written by Jake Holmes, who had opened for The Yardbirds at the Village Theatre in New York’s Greenwich Village the previous summer. McCarty and Page were so impressed with it that they went out the following day and bought a copy of The Above Ground Sound Of Jake Holmes, specifically to hear Dazed And Confused again. The band reworked it, with different lyrics by Relf, into the electric cathedral you can hear on Yardbirds ’68.

“Jimmy’s always been funny about that,” Chris Dreja says, laughing. “I did the first bass line for that song, you know? No one knows that, but I did.”

McCarty is similarly lighthearted on the subject. “I think that was to do probably with trying to protect Led Zeppelin.” He insists he “never really thought about” enquiring into the question of royalties. “I didn’t really listen to Led Zeppelin until some years later. And everyone, including The Yardbirds, were always lifting ideas and making them into their own.”

“I’m very fond of what Jimmy has done with it,” Dreja adds. “And what he’s done on this album is fucking dynamite! He’s a very clever man.”

“When I heard those tracks after twenty years or so,” says McCarty, “I thought: ‘These are much better than I remember.” There is also a second collection of tracks that comes with Yardbirds ’68: eight tracks of demos recorded in New York on the same trip, under the title Studio Sketches.

Some of these tracks – such as the rollicking band composition Avron Knows and the mystical drifting Spanish Blood – have been released before, on the Cumular Limit Yardbirds collection of 2000. Of most interest to hard-core Zep-heads on Yardbirds ’68 will be the track Knowing That I’m Losing You – better known these days, with an extra verse and somewhat fuller arrangement, as Tangerine, from Led Zeppelin III.

Chris Dreja admits that in the past he had felt “a bit cheated” by what he courteously calls the “overlap” between The Yardbirds and Zeppelin. “I mean, Jim McCarty was more involved in the writing [of Knowing That I’m Losing You] than I was. But all these years later there’s a real buzz about having the original Yardbirds version out there. Jimmy’s like, that’s what happened, that was it, but we got over it, sort of thing. So we’ve moved on.”

Indeed speaking with McCarty and Dreja, the feeling now is one of positivity and bygones. McCarty goes as far as to suggest that the live version of Dazed And Confused on the Yardbirds ’68 album is better than the version record by Zeppelin six months later. “I like Keith’s voice better. And all credit to Jimmy, what he’s done with these old tapes really shows just how good the band was at that point, despite me and Keith wanting to step back once that tour was over.”

Another fond memory McCarty has is of the time he visited Page just after Zeppelin formed. “I was still friendly with Jimmy, and I remember when he’d recorded the first Zeppelin album I went down to his house and he played it to me and I was very impressed. But I could see, you know, I could hear the similarities with our sound. And some of the songs, as you said, ‘overlapped’.” Another wry chuckle.

While Page went off to form what quickly became the biggest band on the planet, Relf and McCarty formed the much gentler Renaissance – about as far away from the musical pyrotechnics of the Anderson Theatre show sound as it is possible to get. Dreja went on to become a successful photographer, one of his first big clients being Led Zeppelin – the photos on the back of the first Zep album are his.

Years later, Page would recall: “Having played with The Yardbirds in America where they had all the underground circuit, the Fillmores, and the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, all these sorts of places, there’d been a real following for what we were doing in The Yardbirds. So when they folded I thought, well, I’ve just got to continue. I know what the climate is, I know what the radio situation is over there. I know we don’t want to do singles. So that’s going to be the first thing I’ll be saying. And I knew I wanted to produce the group.”

All he needed now was a new singer, bassist and drummer…

Jimmy Page producing Yardbirds compilation

The Yardbirds: the shape of things right now

Cuttin' Heads: Sonny Boy Williamson V The Yardbirds

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.