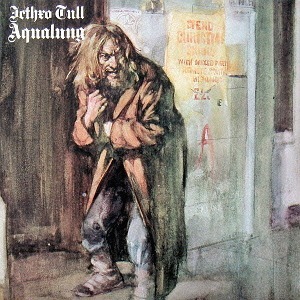

“We had no interest in being rock stars”: The story behind Jethro Tull’s Aqualung

Ian Anderson and Martin Barre give the lowdown on Aqualung, Jethro Tull's career-defining 1971 record. Just don't call it a concept album...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Readers might have thought that after talking about Aqualung for half a century, Ian Anderson would be fed up with yet more questions about the album. But that’s not so.

“I’m happy to talk about anything,” he says in a calmly positive manner. “Of course, I get asked the same questions over and over again. But it’s no problem, because there are always different ways to answer these. Besides, it’s a compliment that an album recorded so long ago still holds a fascination for many people. And I am grateful for what Aqualung did for Jethro Tull.”

Former guitarist Martin Barre is equally enthused.

“How can I ever get fed up with talking about this album? Both historically and musically, it was so important for the band. I can listen to it now from start to finish, and there’s not one weak song. I’ll admit some of our other albums do have the occasional track that’s not held up well. But Aqualung flows from start to finish.”

At the moment, both Anderson and Barre are having to deal with the consequences of the pandemic and its devastating effects on the music scene.

“I have to accept that doing live shows before 2022 will not be possible,” says the former with a sigh. “Of course, I’m not alone in facing this prospect, but that means losing two years of my professional life and at my age I may not have many left. This is the new realism we as musicians are coming to terms with.”

“I had so many plans for live shows in 2020,” adds the latter. “To celebrate my 50 years as a professional musician. All that was cancelled. However, I have to be philosophical about the situation, and when I’m finally able to get back on the road, I intend to perform Aqualung in its entirety.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Realism is something that pervades the lyrics on Aqualung and these marked out Jethro Tull as a little different from many of their contemporaries. Anderson chose to write about things he’d observed, and he did this in such a way that the songs became mini social documentaries in their own right.

“The world was full of pop stars who wore their hearts on the sleeves. Singers who went on about love, and would only talk about ‘me, me, me’. Now, I am not going to knock what they did, because it was perfectly valid. But I wanted to use what I’d seen and knew about, turning these into stories and interpreting life this way.”

In some respects, Anderson’s lyrical approach reflects what celebrated British moviemakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were doing in the 1940s through such classics as Black Narcissus, A Matter Of Life And Death and The Red Shoes, in that they reflected reality through a prism that offered neither heroes nor villains. Anderson accepts this connection with a comfortable ease.

“A lot of the lyrics I wrote for the album came from visual images. For instance, the person who inspired the title track was a real homeless person. As a photographer, I love walking around taking pictures of interesting people I see or meet. And even when I don’t have actual photos of them, I can see these figures in my mind and that’s projected into the lyrics.

“What I was observing in the songs for Aqualung were not heroes or villains. It’s not black and white like that. This is not the way life works, where you divide people into these categories. So, from that point of view, yes my lyricism here did have a relationship to the way certain filmmakers operated.”

For Barre this is the album that showed Anderson had emerged as the de facto leader of Jethro Tull.

“Ian had changed a little in the way he drove himself. He was so focused and intense on the songwriting side, and had become a major force. Because of him, this record was a lot more planned-out than our previous three.”

Anderson tackled some very contentious issues on this album, and none more so than teenage prostitution on Cross-Eyed Mary. Yet, while the subject of a schoolgirl reduced to such circumstances could easily have been a sordid tale, somehow Anderson gives it a sense of innocence.

“The subject of paedophilia is, of course, very controversial, as it should be. But I was reminded of something that happened to me when I was a child. There were workmen digging up the road where I lived, and I was invited by one of them to go into their hut for a cup of tea and a biscuit. My mother, though, warned me not to accept the invitation, yet never explained why I shouldn’t. I’m not saying this workman had any sexual designs on me; it could have been literally having tea and biscuits. But my mum had definite concerns, which, at my young age, I couldn’t fathom.

“When I was growing up you could have a different view of why grown men may stand outside school gates and look at children through the railings without any sexual connotations.

It might have been accepted as people gazing at their lost childhood. Of course, so, when I wrote Cross-Eyed Mary I did it not tackle it from the point of view of the horrific exploitation of a schoolgirl, but from the angle of the sad and lonely men she met and to whom she gave some comfort.

“These days I couldn’t think about writing lyrics with this attitude. It just wouldn’t be acceptable. And rightly so. We are living in a world where paedophile behaviour is properly seen as disgusting. But while you can pull down statues of those who are now seen as representing slavery, for instance Edward Colston in Bristol, and try to airbrush them from history, I cannot rewrite the lyrics for Cross-Eyed Mary. They exist for all time the way I did them back then. Not that I would want to do this. I feel people have to understand the story I was relating, and appreciate that in no way was I ever condoning paedophilia.”

Barre strongly defends Anderson’s lyrical approach on Cross-Eyed Mary.

“None of us ever had an issue with Ian’s lyrics. We never asked him to change anything. In the early 70s you could write lyrics which were about an underage prostitute and nobody would think it was shocking. Look at a comedy series such as Fawlty Towers, and the way they dealt with issues like the Germans. That was seen as funny back then, with no accusations of racism. Now, it does make you wince a bit. But to use a cliché, these were products of their time. Of course, if you tried to write a song now like Cross-Eyed Mary you could have real problems. But you have to put this all into the correct context.”

Tull were prepared to talk about issues on Aqualung which, if not taboo in that era, were certainly not encouraged. Cross-Eyed Mary was one example, but the title song discussed homelessness and Locomotive Breath brought population control into focus.

“I found it easier to write about what I observed and experienced, rather than the fantasy world, where other bands preferred to reside,” explains Anderson. “I like to think this approach resonated with the listener and gave the album an extra relevance. Because people knew that I understood the subjects I was talking about. I had firsthand knowledge to buffer me.

“I would never claim to be the first to do this. And personally I’m drawn to others who follow a similar path. You can obviously put Bruce Springsteen’s albums into the same category as Aqualung, in that he writes about what he knows as well. It’s all about New Jersey and the characters he’s met. Not that I have ever been tempted to write about the New Jersey shoreline. I know nothing about it, so why would I want to come up with a song about that area? However, we do share this enthusiasm for realism.”

Anderson was able to expand Tull’s repertoire for the album by bringing in extra influences, as he outlines:

“It was my opportunity to bring in a singer/songwriting style. That was because I was able to do a lot of the writing on my own. In the early days of touring we had to share hotel rooms, which meant of course there was no privacy. We couldn’t get away from one another, and as a result I could never sit down and just write whenever I wanted. But for the tour just before I wrote the songs for Aqualung, we finally had the good fortune to be able to afford separate hotel rooms. That was the freedom I needed to sit down and write whenever I wanted, with no interruptions. It meant I could develop ideas for these songs.”

Is it fair to see this album as virtually an Ian Anderson solo album, given that he seems to be the one who wrote the songs and defined the direction? The man himself certainly disagrees with this view.

“It was a band album. But someone had to make sure we didn’t get into a rut, because we’d had a little success already. And that ended up being me. I just seemed to have more determination than the others. But if this had really been a solo record then it would have sounded different, and as a result it may have flopped.

“All of us played a key role. Martin’s guitar work was superb throughout, and John Evan’s keyboards added texture and colour. I never sit down and try to work out exactly why Aqualung works so well as an album. There are too many factors involved. But it kicked us into gear, and for the first time made me realise Jethro Tull had a future.

“I get why people think it’s my solo album. And because I had a free hand, a lot of the album was done by me on my own. I could go into the studio without the others, and do guitar parts and vocals as I saw fit. Once this was achieved to my satisfaction, then the rest of the band would come in and add what they needed to do, changing things as they went whenever that felt necessary. So, while I was working a lot of the time on my own, I have never claimed – and never would – that I did this all by myself. It’s the same way that Roger Waters was the man who guided Pink Floyd on a lot of their great albums, but needed the others to step up to the mark, The input from the rest of the band was invaluable in shaping this album. It was a team effort. I was perhaps accepted by all as leading the band, but I was never a dictator.”

Anderson recalls the occasion when he first played passages of the Aqualung track to Barre.

“It was in my hotel room while we were on tour in America. I can’t recall now where we were but I had my acoustic guitar with me and played the idea for the big riff in that song to Martin. It sounded very quiet in that room, and took a leap of imagination to appreciate what this could sound like in the studio when performed by a master like Martin. But he got what I was constructing, and did a fine job bringing this to life.”

There were two significant line-up changes in the band. John Evan was brought in as a full-time keyboard player, while Jeffrey Hammond replaced Glenn Cornick on bass. Barre recalls Evan with huge respect:

“John had played on Benefit as a session musician, so we already knew what he was capable of creating. His addition was such a bonus for us. John was a tour de force as a piano player and also as an arranger. Listen to his work on My God and Locomotive Breath – it’s outstanding. The intro he came up with for the latter track may seem simple. However not only was it appropriate, but later keyboard players we had struggled to recreate what he did. It was very clever and so hard for others to match.”

Hammond, though, was another matter. Barre remembers that he could barely play the bass when he was hired!

“That’s true. Ian and I sat for days at Ian’s house in Haverstock Hill, London, and literally taught Jeffrey how to play the bass from scratch.”

It now seems incredible for a band of Tull’s stature to have a member who was unable to play his instrument. But the guitarist is very forceful in his defence of the decision:

“Jethro Tull were all about character and personality. We were about being different from any other band. There was no way we wanted a virtuoso. What were after was someone who could adapt and alter his style as we went along.

“Because Jeffrey learnt how to play the bass when he came into Tull that meant he created his own sound. When you hear Hymn 43 or Cross-Eyed Mary, Jeffrey was doing stuff no other bassist would have played. He had a unique style and that suited where we wanted to go. This would never have been possible with an experienced musician.”

Barre himself got something of a shock when he did the solo for Aqualung at Island Studios in London, as Anderson vividly remembers with a chuckle:

“As I think a lot of people know, Led Zeppelin were in Island Studios at the same time as us, working on their IV album. They were in the smaller, cosier room, which was in the basement of the building. We were in the bigger room, which was in a converted church. It was very cold and echoing in there. Zeppelin had block-booked their studio, but whenever they took a day off, we were able to use it, which helped with the sound quality.

“Did the two bands meet? Well, only on the stairwell. Personally, I would never have dreamt of going down to where they were to see what was going on. I felt that could be seen as rude by Zeppelin. However, Jimmy Page did come over to where we were once, knocked politely on the door and spent a little time with us.

“Now, Martin was working on his solo for Aqualung at the time Jimmy came in. He was actually recording it when he looked up at the control room and saw none other than Jimmy Page in there – listening to what he was doing! I can’t imagine what was going through Martin’s mind when he realised Jimmy was with the rest of us, and watching every move he made. Talk about being under pressure! But Martin thankfully rose to the occasion, and as we know his solo was wonderful.”

“I recall the incident very well,” adds Barre. “We barely saw anything of Zeppelin when we were at Island Studios. The only member of that band I met was John Paul Jones, and that was on one occasion in the coffee station. Then, when I was doing that solo for Aqualung I did see Jimmy Page waving madly at me from the control room. But I was so into the moment of doing my solo, and didn’t want to lose any of the momentum, that I dared not wave back. In fact, I had my back to Jimmy as I carried on, and what you hear was the first take. He probably thought I was rude, so if he reads this I want to say: Jimmy, I apologise, but I’m sure you’ll understand that nailing the solo had to be my priority.”

While it’s now regarded as an iconic album, Anderson freely admits that at the time the band themselves didn’t know how Aqualung would be received.

“I recall sitting in an all-night café with John Evan just after we’d finished the last recording session for the album. It was about 6am, and I said to John, ‘Well, what do you think?’ He looked at me and replied, ‘I don’t know. What do you think?’ We honestly had no clue whether people would be impressed with what we’d done or dismiss it.

“When copies were sent out to the music press, I admit to feelings of trepidation as to what the reception would be. Thankfully, though, as the reviews came in most of them were positive and complimentary. That was such a relief.”

“I look back now, and have to admit that when we came into doing this album, all of us in the band were perhaps just a bit too comfortable with where we were,” admits Barre. “We’d already had some success. We all had wives or girlfriends, nice houses and cars. And as a result we’d lost our edge. So we struggled a little to kick ourselves into gear to make the best album we could. That’s why it was important Ian took control and gave us the wake-up call that was so desperately needed.

“Some of the songs here were done virtually by Ian on his own. Cheap Day Return is one example. When he played this to the rest of us, it was finished; he’d gone into the studio on his own and done it superbly. There were other songs, though, where we all got involved, chopping and changing parts around, rearranging the music. My God started with an acoustic guitar idea that Ian had. He played this to us, and we all helped to develop it into the song everyone now knows.

“I recall that we struggled to get all the backing tracks done, simply because we were self-satisfied and didn’t have the crucial momentum. One thing I recall is that we developed Locomotive Breath in the studio from a backing track that was literally a bass drum part played by Ian. That was it!”

Barre played a lot of the guitar parts not through massive amplifiers, but went in the opposite direction, as he now reveals:

“I was experimenting with tiny amps. All of what I did on Cross-Eyed Mary was done on a very small amp I bought off someone in the street. I just happened to see this man walking down the road with a guitar and this tiny amp. I gave him £1 for the amp, and that’s what I used a lot in the studio.”

There was a serious downside to the usage of this piece of equipment, though. One that very nearly led to a tragedy, as Barre recalls: “The amp’s wiring was poor – I got a major electric shock from it on one occasion. It was when I was doing Hymn 43 and I screamed loudly. Thankfully, one of the studio engineers reacted very quickly and dealt with the situation.”

However, a misunderstanding was coming over the horizon, as some magazines chose to regard Aqualung as a concept album. Obviously it’s not, and readers might have thought that Anderson would be angry at having to address this issue yet again. But oddly, it’s he who brings up this thorny subject, seemingly determined to once more calmly put the conceptual misconception into context.

“I have said this a million times, and would be happy to repeat this a million more times, but Aqualung is not a concept album. Yes, there are themes which link a few songs together. For instance, some of the material deals with religion and my views on this subject. But these are disparate songs which have no overall connection. That was never the plan, and all I can say to those who insist this is conceptual is they have it wrong.

“Perhaps the reason this has persisted is because of the liner notes which were featured on the album. Maybe they gave the impression there was a storyline running through the music. I feel these notes worked out very well, but could have led to a false impression.

“You can never tell how anyone will interpret your songs. In fact, I love keeping things a little open-ended, so there’s room for individuals to take what they want from my music. Personally, I love TV shows and movies where you’re quite sure what happens next. If you are told everything, it leaves nothing to the imagination and I lose interest.”

Barre has his own theory on why some people still see Aqualung as a concept album:

“Of course it’s not conceptual. But it was banned for a while in Spain, because some of the songs deal with religion and are very critical. Maybe people read that about this and believed the entire album was about religion, and then took it a step further by assuming that it therefore must be a theme that ran through all the songs.”

It could also be claimed that part of the reason for the entire conceptual misdirection came about because the band insisted on giving subtitles to each side of the vinyl. So, Side One was dubbed Aqualung and Side Two called My God.

“When it came to sorting out the track order for LPs, you had to take a lot of different factors into account,” says Anderson. “I think there were Tull albums where I got it wrong. But on Aqualung, it works very well. I decided to give the two sides those names as it added some enigma to the situation. Did this lead to the misinformation that the album was conceptual? I can’t say this has ever occurred to me. It is possible.

“I suppose when it comes to Aqualung, this will always be one of the first questions I get asked. It’s so embedded in folklore now that however many times I explain why it’s not a concept album, this will never satisfy everyone.”

The success this album has had might lead readers to presume it was a huge seller from its release in March 1971. But, as Anderson remembers, that wasn’t what happened:

“No, it wasn’t a big hit straight out of the box. It sold steadily, rather than spectacularly. But it eventually did well enough to lift us to that new level.”

In the US, Aqualung was the first Tull album to chart in the Top 10, reaching No.7 in the Billboard Charts. To this day, this remains their biggest seller Stateside; the only album to sell more than a million copies. In fact, it’s been officially certified as having triple platinum status there, surpassing three million sales. Oddly, in the UK it didn’t do as well as the two previous albums. Whereas 1969’s Stand Up topped the chart and Benefit a year later made it to No.3, Aqualung stalled at No.4.

Today, the global sales figure for the album is impressive, to say the least, as Anderson reveals:

“I recall reading several years ago about how one of Coldplay’s biggest albums – I forget which one – had sold 11 million copies worldwide. That’s an incredible number. But when I checked the figures for Aqualung, it showed that 12 million copies were sold to that time. Naturally, you have to bear in mind that Coldplay had done it in 12 months, whereas it had taken us about 40 years to reach that landmark, but this proves how big the album was, and how it still sells consistent amounts every year.”

Barre dismisses any thoughts that the band were under pressure to come up with a major-selling album:

“We were outsiders. We weren’t a glam rock band, nor were we heavy rockers like Zeppelin or Deep Purple. If anything, we were anti-heroes who were proudly different to anyone else. We actually had an attitude that I would describe as punk a few years before that became trendy.

“We had no interest in being rock stars. We didn’t want to fly around in private planes and have groupies and drug dealers waiting for us everywhere we went. None of us were bothered with all that nonsense. What mattered was getting musically better with every new album. There was no formula to what we did, and that gave us the freedom to do whatever we felt could work.

“So because we had this approach, there was never any pressure on us to come with a hit single or to sell millions of copies. We were left to our own devices in the studio.”

Now, fans take it for granted that the album title is Aqualung. But for Barre, there wasn’t an obvious choice.

“There was no track on the album which stood out as representing the album, and therefore the one we should pick as the overall title. So when Ian told us he wanted to go with Aqualung it’s not as if any of us had a convincing alternative.”

Barre also doesn’t believe there’s a clear reason as to why the album became such a big seller.

“There wasn’t a eureka moment, when all of us knew this was going to be a defining moment in the band’s career. It’s as simple as being the right album at the right time, and also the fact that there were so many great songs. You have to be a little lucky if you sell as many copies of an album as we did with Aqualung. But everything aligned in our favour.”

Anderson never underplays the importance of Tull’s fourth release in establishing their presence as a major force.

“If you look at what had happened to our previous albums, This Was [1968] had some very limited success, but didn’t give us any international profile. Stand Up [1969] was more successful and allowed us to the do our first tours both in Europe and America. And Benefit kept it all ticking over nicely. You could rightly claim that by the time we got to Aqualung, the band were at a watershed moment in our young career. We could either reach out to another level, or else resign ourselves to a steady decline from hereon in.”

Thankfully for all of us, the former is what happened. And this is the album that, for many, defines the Jethro Tull sound. While Anderson doesn’t fully accept this, nonetheless he concedes an understanding of why it’s seen this way by fans:

“To me, what we did was a synthesis of all that had gone before. We didn’t lose what we had done previously. So you can still hear elements of the blues on some of the songs, but we also had other stuff brewing in the background. There were heavy riffs, psychedelia and folk. We were expanding our horizons, but from what was already a firm foundation. That’s what you did as a band. You never want to stand still and repeat yourself. However, you were also aware of what you’d done that worked.

“Was this the blueprint for all that came later? I wouldn’t be as simplistic as that. However, we took aspects of what we did here into later albums. From a lyrical stance, there was a recognition that I could create characters capable of holding the interest. These were taken from observing real people in real places, and making the listener want to know what happened to them. It puts you into a setting and context.

“I developed the notion of carrying my camera with me and snapping photos of anyone I came across who stood out because they were different. These could inspire a song idea, as happened with Aqualung. But I have always been very mindful of not infringing anyone’s privacy. For instance, I was recently in Hyde Park when I saw a [homeless] lady emerge out of the mist. She was dressed in a, shall we say, careful manner. I was going to take her picture, then I thought to myself that this would be stepping over the mark, so I avoided the temptation and walked away.

“What this approach has meant is that I can immerse myself in the character of those I’m singing about in the lyrics. I become an actor, in the way that David Bowie, Alice Cooper and Alex Harvey did. It’s not Ian Anderson you’re listening to, but the role I’ve adopted. And it really began with this album. I suppose it is fair to say that I found my niche here.”

Barre is still excited when he discusses what Aqualung means to him:

“It was not just a step forward for Jethro Tull but also a step up. This is when we could start to play very big venues and think about putting on a show for the fans. We took it all in our stride, and it’s only now that I can look back objectively. But I have to admit to getting a thrill when I listen to the album these days. It excites me, because those were amazing times for us. It certainly stands the test of time.

“Ian was at the top of his game. And thank goodness he had the tenacity and vision to push us as far as we could go. Was it an album full of serious social comment? I suppose Ian did have some issues he wanted to tackle and did it all intelligently. But for me, the songs were about being entertaining.

“I can’t say this is the best album we ever did, but it’s certainly the most consistent, and I can see why for many fans, Aqualung is the Tull album.”

“The world is very different now from the way it was 1971,” concludes Anderson. “That much is obvious. What Aqualung does is allow everyone a glimpse back at a bygone era. However, much of what I talked about in these songs 50 years back remains as relevant now as it was then. If not more relevant. Maybe that’s another reason why the album is not another piece of whimsical nostalgia, but one that connects strongly with audiences of all ages. Not many albums from the early 70s can claim this, however good they are.”

Originally printed in Prog Magazine #117

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.