“Strange people just appeared. We had awful visions of ghosts in the room. There was rustling and scraping at the window. It was happening every full moon”: The creepy tale of Camel’s Moonmadness

Charged with matching The Snow Goose’s surprise success, Andy Latimer’s band wrote a record about themselves – disguising their vocals because they’d been told they couldn’t sing

After Camel’s 1975 album The Snow Goose achieved unexpected success, the band’s label demanded something similar for 1976. Instead Andy Latimer’s band dramatically changed direction. The gamble that was Moonmadness paid off, resulting in the creation of an all-time classic prog release. Latimer looked back in 2019.

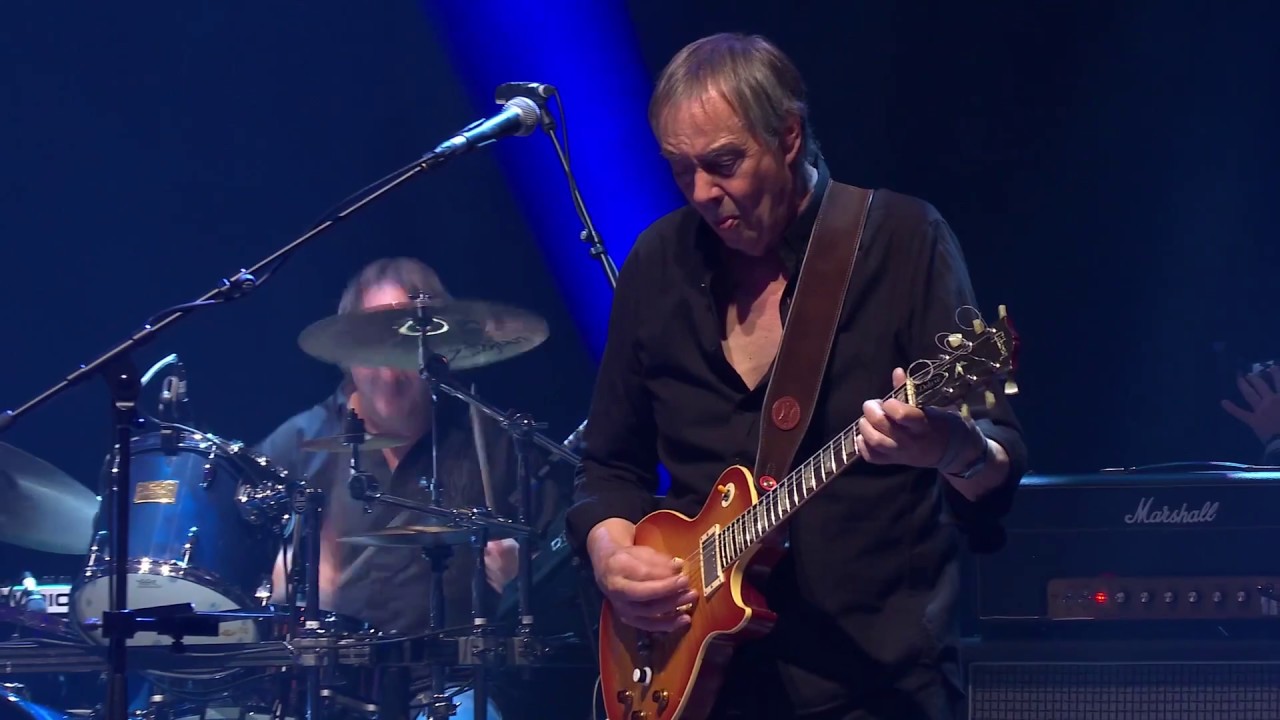

In the hot summer of 1976 Camel were one of the biggest bands in the country. Riding high after the huge success of the preceding year’s conceptual extravaganza The Snow Goose, the band formed by guitarist Andy Latimer in 1971 had passed steadily through the progressive rock ranks and were now, seemingly, on the cusp of even greater success. Their next move would turn out to be their smartest of all: their fourth album is widely regarded as their finest work – not to mention their most enduringly popular.

Released in time for a legendarily drought-ravaged season, Moonmadness was the ultimate showcase for the classic line-up of Latimer, keyboard player Peter Bardens, bassist Doug Ferguson and drummer Andy Ward. Fast forward to 2018 and the current line-up are out on the road again, revisiting the record in its entirety onstage. Thinking back to the mid-70s, Latimer admits there was no clear plan as the band embarked on the follow-up to their breakthrough album.

“We were in a bit of a quandary about it,” he chuckles. “It was a bit like, ‘Oh God, what are we going to do next?’ Probably because none of us were that sensible, we said, ‘We want to do something totally different.’ We should have just done the Son Of Snow Goose.”

The heat was on to produce another hit – the Decca label had been pleasantly surprised by the huge success of their 1975 title, which they’d been distinctly concerned about prior to its release. “We were always under a lot of pressure from the management and the record company to do something they could sell,” Latimer recalls.

“When we gave Decca The Snow Goose they were quite horrified that it was one piece of music with no breaks. How could they get it played on the radio? So we were getting demands to do more commercial stuff, but we resisted. We were pretty arrogant. They weren’t too bad, Decca; they left us alone to do our stuff to a degree. But there was always that element of, ‘How are we gonna sell this?’”

Admirably resistant to the notion of repeating themselves, chief composers Latimer and Bardens began to pool their ideas. They disappeared into deepest, darkest Surrey to get the compositional ball rolling. But all was not as it seemed. “We were writing in this place out near Dorking somewhere. It was a really nice barn, a great place to write, but it was a bit strange,” Latimer recalls.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“The people there were a bit strange. You wouldn’t sense they were in there, they just suddenly appeared. Pete and I had these awful visions in the night where we’d wake up and think there were ghosts in the room. There was rustling and scraping at the window. It was all getting a bit funny. It seemed to be that every time there was a full moon it was happening. So we started thinking about the moon and the madness of the full moon, and that’s how the title came about. There were some very strange things going on at that place.”

Supernatural interference aside, Latimer fondly recalls a major pinnacle in his writing partnership with Bardens. At a time when successful bands were given a decent amount of freedom to pursue their most ludicrous ideas, the duo’s confidence in each other led to an almost unassailable certainty about the band as a whole. Consequently, the group itself would become the focus of the new material.

“In those days the situation was idyllic; we’d go off to some cottage in the wild somewhere, and it was a lot of fun,” Latimer enthuses. “Pete and I, from my point of view at least, had this great writing relationship. That’s not an easy thing to find. I’ve often tried to find somebody else like Pete and it’s really difficult. It’s just something that clicks, when you’re a team like that.

“Eventually we came up with this idea of basing the next album on the four individuals in the band. We looked at each of us – and, of course, Andy Ward and Doug Ferguson were the easiest. Doug was so solid and straightforward in some ways, and Andy was definitely a free spirit. Then there was Pete and I. It’s always hard writing about yourself, but after a lot of talking, I think we got the essence of what each individual was all about.”

Two major decisions were made. Firstly, Latimer and Bardens would write one song for each member of the band, focusing on their personality, musical identity and strengths within the group. Secondly, Moonmadness was to be an album with lots of vocals and melodies. “We definitely wanted to get more into singing,” Latimer notes. “It was a challenge because none of us in the band were really great singers. Our producer for the first album, Dave Williams – bless him, he was a lovely guy but not very tactful – he’d said, ‘So who’s singing? Because none of you can sing!’ We all felt a bit like, ‘Er… what?’

“So we took a break in recording and held auditions for about 40 would-be vocalists. All these guys who thought they were great singers were awful. We figured we could sing better than them. But it gave us a little bit of paranoia; when it came to Moonmadness, we didn’t have that much confidence about any of our vocals. So we had to be really inventive about it. We’d disguise them in lots of ways, using Leslie speaker effects and phasers and all those kinds of things, and then not mixing them too loud. I think it gave the album a certain mood. A lot of people like the treatment we did on the vocals – but and we only really did it to cover them up!”

I thought that to be a good guitar player, you had to play a lot of notes. A couple of albums after that I felt, ‘Hang on – my brain doesn’t work that fast!’

Moonmadness was recorded at London’s Basing Street Studios in January and February 1976, with esteemed engineer Rhett Davies (Genesis, Brian Eno, Roxy Music) manning the controls. Armed with a batch of new material that they instinctively felt was the best possible forward step, Camel were a very focused and united unit. Extensive touring had honed the band’s shared chemistry to a state of near-perfection – something they were eager to capture on the new album.

“The band were really solid,” Latimer agrees. “The relationships were really good. No rot had set in yet. We really liked to rehearse, so we’d rehearse every day we weren’t actually gigging, and we gigged a lot in those days. We were just consumed by it. I don’t think many of us had relationships outside the band. Everybody was living together and it was very productive. I suppose it was a simpler time.”

Latimer praises Davies’ contribution. Having engineered Genesis’ Selling England By The Pound, the producer had nothing to prove, but his freewheeling approach to making records had a profound effect on Moonmadness’ unique vibe. “The whole thing was recorded very fast; Rhett was a lovely man and a fantastic engineer. He encouraged us to be silly and to explore all these daft ideas. Andy Ward would be blowing a pipe into buckets of water to simulate sounds on the moon. On the song Air Born, he was smoking a joint, and in the middle section you can hear all this inhaling going on. It was all very hippie, I suppose, but very funny.”

The four songs dedicated to the band members are arguably among the band’s greatest pieces. As Latimer recalls, the process enabled them to venture into territories they hadn’t previously considered – particularly with regard to Ward, for whom Latimer and Bardens wrote dynamic instrumental closer, Lunar Sea. “Let’s just say that Andy, had an excessive personality, so he was always being silly,” Latimer recalls. “He was an incredibly talented drummer; because he’d worked with us from the beginning, he always knew what we wanted. But he was always the quiet guy of the band, in an odd kind of way – somewhat against what you might think. He was into a lot of things, especially jazz. So when we started writing we knew his song was going to be fairly jazzy and complicated. Not jazz in the proper sense, because none of us were proper jazzers, but it was what we considered jazz, I suppose!”

Nine minutes long and, by any sane reckoning, one of the most exhilarating prog epics of all time, Lunar Sea exudes a euphoria that speaks volumes about the unity and shared enthusiasm that drove Camel in the mid-70s. As Latimer remembers, it stretched the band to the edge of their abilities. “We’d just supporting Soft Machine for a week and that had made quite a big impression on Andy and I. We used to sit at the side of the stage because they had John Marshall on drums, who Andy really liked, and Allan Holdsworth on guitar. Obviously I was just thinking, ‘Oh my God, what is he doing?’

Pete’s voice wasn't really very proggy. We thought, ‘Let’s stick his voice through a Leslie.’ The effect was like the sound of a river, giving it a bit of mystique

“At that stage I thought that to be a good guitar player, you had to play a lot of notes. So I was trying to play a lot of notes on Lunar Sea. A couple of albums after that I felt, ‘Hang on a minute – my brain doesn’t work that fast!’ so I started to just be me and play melodic stuff. But that was where Lunar Sea came from. There was a lot of energy from Andy, because it wasn’t easy to play as a drummer. He loved it because it was such a challenge.”

For bassist Ferguson, Latimer and Bardens wrote the strident and punchy Another Night – the most straightforward song on Moonmadness by some distance. “Doug was the organiser and the peacemaker, when Pete and I were going at it. He’s very organised and a bit sergeant-majorish; he picked up the money and drove and got us organised. He was also very solid as a bass player. And he always had an amazing amount of stories… I couldn’t tell you many because they’re a bit risqué! He was always disappearing at night and walking the streets, doing silly things, so we came up with Another Night.”

Significantly, today’s Camel perform a version of Another Night that, while still relatively true to the original, packs more of a straight-ahead punch than the revered recorded version, bringing it closer to Latimer’s original vision. “I wanted it to be heavier and more straight-ahead rock’n’roll, but Andy and Doug put this little skip beat in there, which sort of took the power away from it,” he remembers. “It wasn’t what I wanted, but you compromise in a band. Sometimes that’s a challenge because you see a picture in your head when you write something. But you respect what the rest of the band bring to the table too, so it worked out fine.

Having successfully summed up their rhythm section, the writers’ next task was to write about themselves. For Bardens they wrote the intricate and mischievous Chord Change, one of the most overtly complex songs in the Camel canon and one that Latimer feels neatly sums up his late friend. “Pete could be very changeable, so I thought we needed a piece with a lot of changes. We decided to do something like that, with the complexities in Pete’s writing coming through. Although we were writing together, each of us was stronger in different areas. So the beginning part of Chord Change is mainly Pete, then I wrote the more melodic stuff, the guitar breaks and things; but it was still a very good joint effort.”

One of the most beautifully mellow of Camel’s songs, Air Born is a shimmering, hazy affair that almost casually sums up Latimer’s famously laid-back and humble demeanour. In fact, it was meant to portray its subject as the prog rock equivalent of a Ralph Vaughan Williams symphony – windswept, rain-bothered and English to the core. “It was a bit pretentious!” Latimer laughs ruefully. “I wrote the beginning and thought, ‘This is what I feel is really English!’ I was imagining woods and fields and all that stuff. Trying to write about ourselves is hard; it’s difficult to look at yourself and think, ‘Who am I? How do I come across to people?’”

We had a sleeve we were happy with in England. Then we heard back from America: ‘Oh no, it’s too subtle.’ They came up with this camel in a spacesuit. It was incredibly funny

The remaining songs on Moonmadness may not fit into the album’s vague concept, but they all exude that same sense of a band hitting their artistic stride with great aplomb. In particular, Song Within A Song is a fairly safe bet for Camel’s most popular track of all, its mellifluous drift a definitive snapshot of what they were all about in 1976. Written while Latimer and Bardens were still mulling over ideas for the follow-up to The Snow Goose, the guitarist attributes it one of those precious moments of magic, when great ideas collide.

“It was something that Pete and I just wrote, at a time when we worked really well together. When he had a great idea I’d just let him go with it, like, ‘Go on, more of that! Keep that bit! No, not that bit!’ Then if I’d got the bit between my teeth, he’d let me go. So it was very much a give-and-take relationship. That’s how Song Within A Song came together.”

Similarly, the album’s gentlest moment, Spirit Of The Water, was simply a piece of music that Bardens had written and that Latimer loved. “The only I contributed to that was the title. I’d just read a Henry Williamson book called Salar The Salmon and there was a line in it, something about ‘the spirit of the water.’ I told Pete it would make a good title. So he went away and wrote this song and it was fantastic – he didn’t need to change anything. I suggested we put recorders in between the verses, but that was it.

“Also, Pete wanted to sing it. His voice was a bit like Mick Jagger’s, not really very proggy; so we thought, ‘Let’s stick his voice through a Leslie,’ which you hoped would disguise the voice. In the end the effect was like the sound of a river – very atmospheric and redolent of water, giving it a bit of mystique. It was just a small interlude, but it was so good I said to Pete, ‘We’ve got to do this!’”

Finally, or perhaps firstly, there’s Aristillus. Arguably one of the most recognisable album openers of all time, the eccentric Wurlitzer intro provides Moonmadness with a suitably perverse and mischievous starting point. Written and performed by Latimer, with some slightly unorthodox assistance from Ward, it fitted perfectly with the album title. “I’d written that piece at home and I didn’t have a title,” Latimer says. “I took it to the band and Andy came up with Aristillus. I said, ‘What’s Aristillus?’ He said, ‘A crater on the moon.’

“Then he found another crater, right next to Aristillus, called Autolycus. So he said, ‘Let me try to say the words, really quickly, all the way through the track.’ It was incredibly difficult – he kept on laughing and he was going, ‘Aristillus, Autolycus, Aristillus, Autolycus…’ We were in absolute hysterics!”

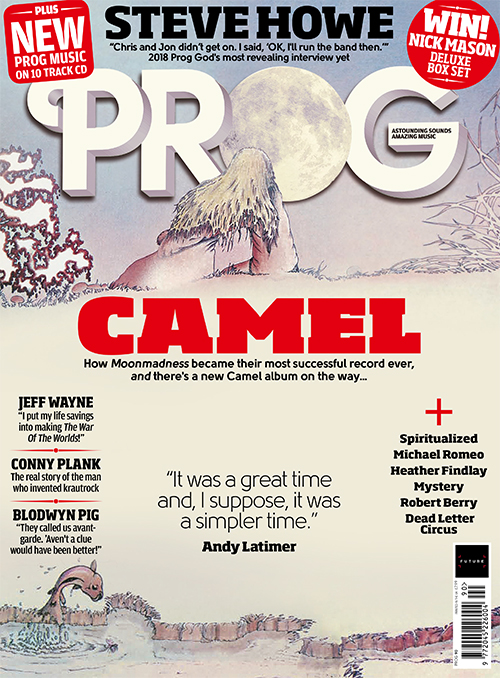

Moonmadness was released on March 26, 1976. In the UK and Europe it arrived adorned with its iconic, subtly psychedelic sleeve, designed by artist John Field. In the US, however, it emerged with a different cover, its cartoonish artwork depicting a camel, wearing a spacesuit, on the moon. Luckily, the band saw the funny side. “We had a lot of trouble with the sleeve in America,” Latimer admits. “We had a sleeve that we were happy with in England – it was a gatefold too, which is something the record companies put a stop to because it gets expensive. Then we heard back from America: ‘Oh no, it’s too subtle, we don’t like it.’ so they came up with this camel in a spacesuit, which we thought was incredibly funny. We used it on a lot of merchandise later on!”

Although its initial sales were a little disappointing in light of The Snow Goose’s success, Moonmadness eventually reached No.15 in the UK album charts, seven places higher than it predecessor had achieved, and went on to become Camel’s bestselling release. At the time the critical response was distinctly mixed, with some claiming Camel had lost their way and others hailing their ongoing evolution. For Latimer, the process of making it had been so enjoyable, and the results so satisfying, that any murmurs of disquiet were easy to shrug off.

“From what I can remember, the response was okay,” he says. “You know what it’s like. You’re Fleetwood Mac and you make Rumours and sell 20 million and then you make Tusk and it only sells five million. It’s hardly a failure, is it? Moonmadness didn’t really do well initially, but we just went, ‘Oh well, let’s move on and do something else!’ It wasn’t a major blow to us if something didn’t sell. It’s easy to look back and think, ‘Well, that was a mistake.’ But it’s all part of growing up, – and I don’t feel that way about Moonmadness.”

Dom Lawson began his inauspicious career as a music journalist in 1999. He wrote for Kerrang! for seven years, before moving to Metal Hammer and Prog Magazine in 2007. His primary interests are heavy metal, progressive rock, coffee, snooker and despair. He is politically homeless and has an excellent beard.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.