The story of Camel's epic The Snow Goose

It was 1974, the age of the concept album, when Camel had the idea to set author Paul Gallico’s wartime love story to music.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“I’d read The Lord Of The Rings like everyone does, and I’d written The White Rider on Camel’s second album, Mirage [1974], which was inspired by Gandalf and all that stuff,” says Camel guitarist, flautist and vocalist Andy Latimer with a chuckle. “As we were recording it we said, ‘Wouldn’t it be a good idea to make a whole album based on a story?’ So then we all went off trying to find a good book to base it on.”

By 1974 it was almost de rigueur for progressive rock groups to have written a concept album, or at least a sidelong suite. Latimer doesn’t remember any obligation or pressure from their record company, but he does recall that Camel had been thinking about doing something with an orchestra, following earlier forays by Deep Purple, The Moody Blues and Caravan.

Keyboard player Peter Bardens had favoured a novel by Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha or Steppenwolf. But bass guitarist Doug Ferguson came up with The Snow Goose, a poignant short story later expanded into a novella in 1941 by American novelist, Paul Gallico.

Article continues below“We saw more possibilities in The Snow Goose. It was more defined,” says Latimer, explaining the group’s choice. “There were only three characters and both Pete and I had a clear idea about where we wanted to go musically, so it was an easy task in a way. It was a very powerful story and quite inspiring.”

Its main character, Philip Rhayader, is a disabled outsider who lives in a lighthouse on the Essex marshes. He strikes up an unlikely friendship with a teenage girl, Fritha, centred on their rescue and rehabilitation of an injured snow goose. The subject matter was a perfect fit for the 70s with its themes of the still relatively recent Second World War and of transcendental spirituality. Rhayader dies helping to bring troops back over the channel in his boat during the evacuation of Dunkirk. But when the snow goose returns to the marsh and circles around Fritha before flying away, she interprets it as Rhayader’s liberated soul flying free. The Snow Goose was made into a short film for BBC TV in 1971 starring Richard Harris as Rhayader and Jenny Agutter as Fritha, although Latimer admits he never saw the film at the time.

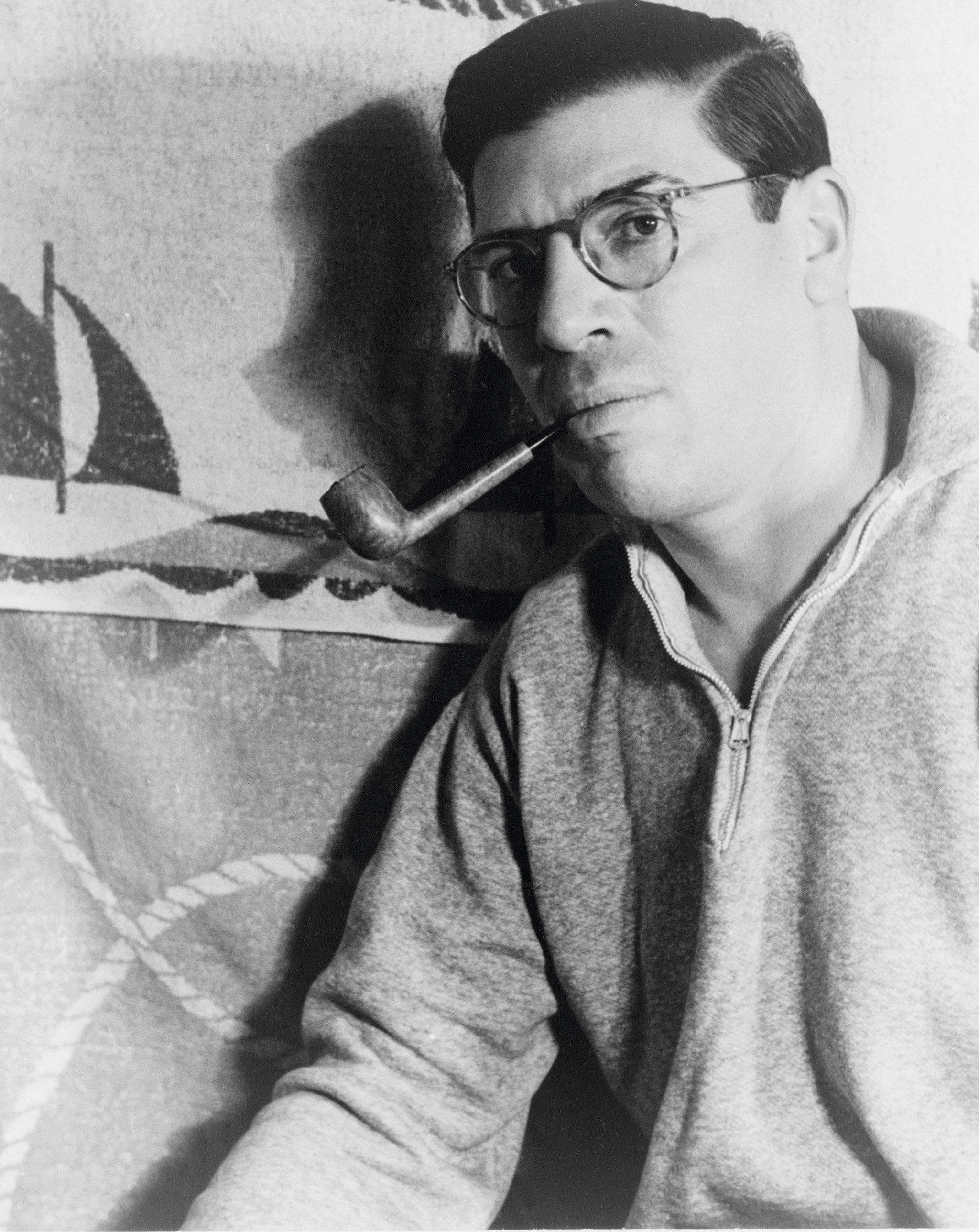

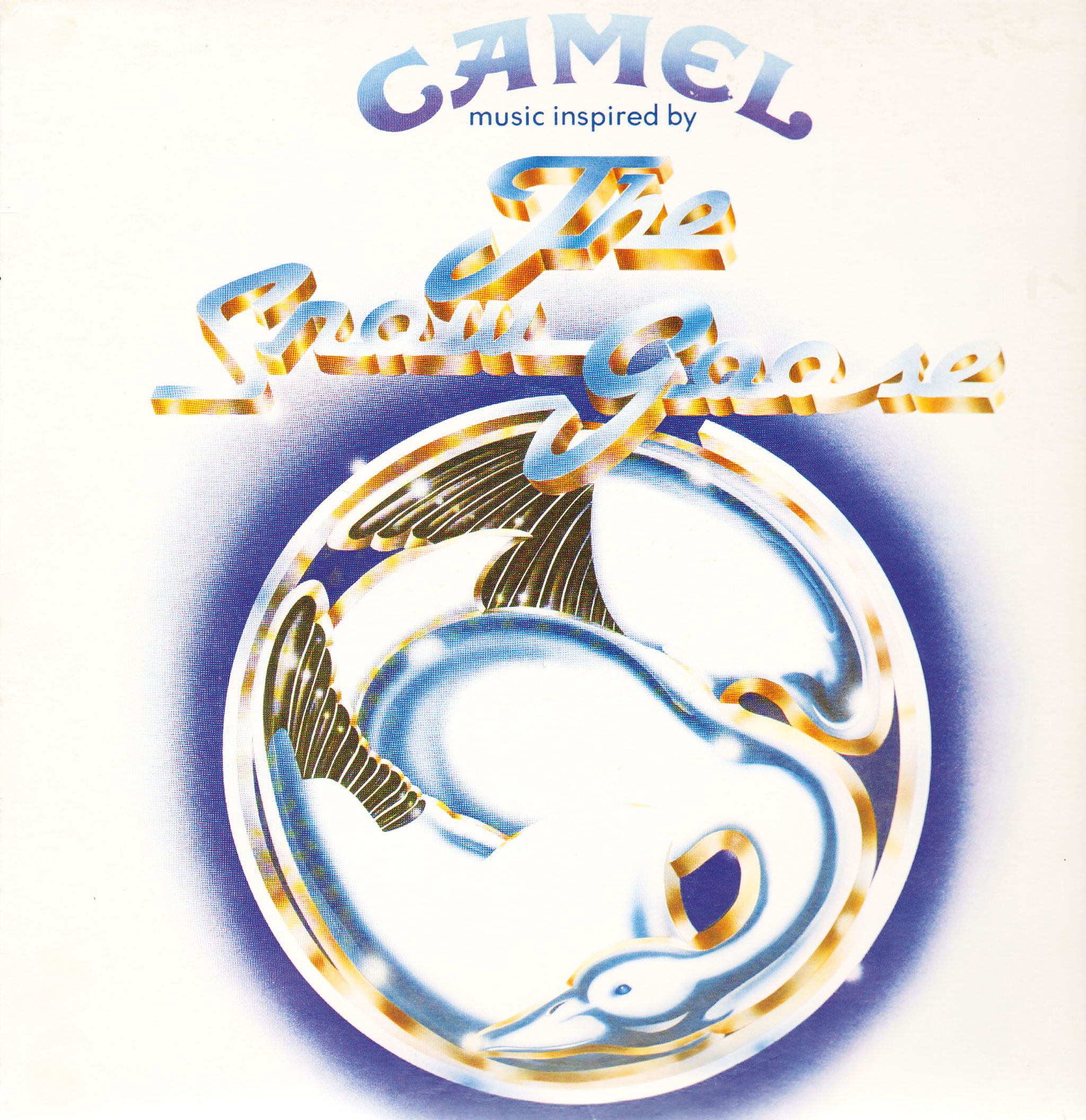

Not a Camel fan: The Snow Goose author Paul Gallico, and (below) the book and offending LP.

Camel’s first concept album could, in theory, have been quite different. In 1974, the group’s manager Geoff Jukes had contacted the European office of Camel cigarettes with the idea of using the typography and imagery from their packets for the album cover of Mirage. The company jumped at the idea of free publicity and sent a small delegation over from Switzerland to meet the group. “They were asking us questions like, ‘Have you got a title for this song?’ We said, ‘No’, and they said, ‘Why don’t you call it Twenty To The Pack?’

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“They were wanting to have girls walking up and down the aisles at gigs with cigarettes,” Latimer continues. “But as a band we were going, ‘No, no, no! This is very uncomfortable for us. We don’t want to have anything to do with this.’ So we told Geoff, ‘You’re going to have to put the kibosh on this.’ Also, the record company in America were uncomfortable about it, because Camel cigarettes were trying to appeal to the older man, so they stopped us using the sleeve. We had to hurriedly come up with another sleeve for America – so there’s a sleeve with some dragon on the front.”

The Snow Goose was > > a very powerful story. We saw the possibilities.

In the summer of 1974, with all notions of making the first concept album on smoking now far behind them, Latimer and Bardens rented a converted farm building in Devon, Cornwall, where they wrote the bulk of the material for the new album in a couple of weeks.

“I can’t recall exactly where it was now, but we noted it was quite near the River Camel,” says Latimer. “It was such an idyllic place, we were young, and Pete and I would just go and sit up on the hills and talk about The Snow Goose, and where we were going to take it.”

On The Snow Goose the characters are portrayed by particular musical themes – like the use of the leitmotif in romantic classical music – which helps bring them alive within the musical narrative.

“We wrote quite a lot of pieces for each character until we found what we thought was right,” Latimer explains. “And in the middle of the recording, we had a three-month tour of America. So we had a lot of time to think about the piece and when we returned we rewrote several of the sections because we weren’t happy with them.”

For the initial recording sessions, the group went into their label’s own Decca Studios in West Hampstead, London. The facility had been running since the 1930s and Latimer is amused to recall its old-fashioned corporate look, with studio technicians wearing white coats and fusty looking characters operating primitive mastering equipment.

Unfortunately the sessions became bogged down, mainly around the recording of the drums. Latimer thinks that the group’s drummer Andy Ward was often ill-served by the Gaffa tape-dampened studio sound that was the order of the day, in order to ensure there were no intrusive rings or rattles.

“I’d say, ‘Nobody’s going to hear that when we play and that’s what you get when you hit a drum kit.’ But they were set in their ways and so you got a very dead drum sound.”

Camel decamped to Island Studios in Basing Street, London, although they later returned to do overdubs and mixing at Decca. The group recorded the album’s 16 pieces with the band playing live, then kept the best rhythm section takes, with keyboards, guitar and other overdubs added later. This was standard procedure at the time to achieve maximum separation and eradicate mistakes, but looking back, Latimer can see flaws in this approach.

“You would often be in the studio on your own trying to come up with a solo, and it was very difficult to capture any emotion as you aren’t playing off anybody. It felt clinical. But that’s the way you did things in those days, you wanted to be as perfect as you could, but I do think you could lose the plot sometimes.”

Although he had enjoyed writing material for The Snow Goose with Bardens, Latimer admits that there was often friction between them.

“From the start, Peter and I had a love/hate relationship. We wrote together really well and it was a very special partnership,” he elaborates. “We conceded to each other’s wishes – when we saw that the other had the bit between their teeth, we’d let them go with it. But we fell out on things like live performances, and recordings could be a little awkward at times, a little tense and stressful. But we were working well as a band at that point and it was generally quite harmonious.”

For the orchestration, producer David Hitchcock approached David Bedford. A modernist classical composer in his own right, Bedford had secured a solo deal with Virgin, and his avant-garde orchestral record Star’s End became the most outré addition to the label’s catalogue on its release in 1974. As well as the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, it also featured Mike Oldfield on guitar and Henry Cow’s Chris Cutler on drums.

Bedford was no aloof classical establishment figure and had entered the rock world playing keyboards with Kevin Ayers’ group The Whole World, after contributing piano and ensemble arrangements to his 1969 debut solo album, Joy Of A Toy. He had also worked with Roy Harper and scored Oldfield’s Orchestral Tubular Bells.

His arrangements for the London Symphony Orchestra on The Snow Goose are typically inventive and sympathetic, including a striking wind quartet on Friendship. But mostly the orchestrations are subtly woven into the music, breaking out more dramatically on La Princesse Perdue towards the end of the album.

“Pete and I were very happy with David Bedford’s arrangements and I think they worked really well,” recalls Latimer. “I wasn’t knowledgeable about such things and it was a bit of an ego boost hearing your music played by an orchestra.”

One of the most haunting moments on the album is likely to remain a mystery, though. A female vocalist was hired to improvise wordlessly over the repetitive guitar arpeggios on the track Preparation, which she did to stunning effect. To this day Latimer regrets that she was never credited and that no one involved remembers who she was.

Then came the sequencing, and as the 16 parts had been recorded separately, the group didn’t really know what they had until they edited it together in the studio. It was the first time they had heard the album from start to finish and they were pleased with the results.

Latimer suggested that the album should come out with the book text: “It’s enjoyable to listen to the album while reading the book as it takes about the same time.” But Paul Gallico and his publishers were having none of it, and their lawyers threatened to stop the album’s release. The group got around this by presenting the album as Music Inspired By The Snow Goose (with the first three words in a noticeably smaller font on the front cover).

One of the reasons Gallico gave for this negative stance was the group’s perceived link to Camel cigarettes. “He was anti-cigarette smoking, which I find interesting because every picture I’ve seen he’s got a pipe in his mouth,” Latimer observes.

However, the main reason was that, unbeknown to Camel, the rights were already tied up in another project in which Gallico was working with songwriter Ed Welch – who’d had a minor hit with ’71’s Clowns – on what the author’s estate still refers to as the ‘official’ album of The Snow Goose.

The ‘official’ album, released in 1976, included narration by comedian Spike Milligan and also featured arrangements for the London Symphony Orchestra. “I quite liked it,” says Latimer. “Of course, at the time I thought ours was better, but Spike and Ed Welch did a great job, although I don’t particularly like the narration.” Camel toyed with the idea of having narration on their album, but as Latimer says, “Music can hold your attention time and time again, but spoken word can interrupt the flow, so we decided against it.”

Listening back, you could hear two brass players chatting when the music was going on, saying, ‘Are you going down the pub afterwards?

Music Inspired By The Snow Goose was released in April 1975. It received a positive critical reception and reached Number 22 in the UK album charts. It was particularly warmly received by the Melody Maker readership who voted the group top of the Brightest Hope category in their end-of-year poll – after four years extant. This prompted relative veteran Pete Bardens to wryly tell MM journalist Chris Welch that he’d become “an overnight success after 10 years”.

However, when the group toured Europe after the album was released, they found that some of the fans enjoyed the music from Camel’s first two albums, but were disappointed by The Snow Goose section. This caused a rethink of the way it was played live as a four-piece and prompted some rearrangement of the group’s parts. Since then it has proven to be a live favourite, with sections played in variously ordered medleys.

On rare occasions the album has been played in its entirety; the most recent time being at Camel’s sold-out concerts at London’s Barbican in 2013.

There were problems, however, with some of the London Symphony Orchestra players when the album was performed at a special showcase concert at the Royal Albert Hall in November 1975.

It wasn’t uncommon in the 60s and 70s for orchestral musicians to view the music of rock bands as hippyish kids’ stuff when compared to ‘proper’ music from the classical repertoire. When composer and arranger Ron Geesin recorded the ensemble parts for Pink Floyd’s 1970 album Atom Heart Mother, he famously came close to fisticuffs with one of the disdainful brass players from the EMI Pops Orchestra.

Camel were blessed with some rather more sympathetic players from the LSO. Latimer reckons they were about 70 per cent into the music, and producer David Hitchcock has previously said that Latimer’s facility with the guitar seemed to capture the orchestra’s attention. But the concert recording was still blighted by some musicians’ unprofessional behaviour.

Latimer takes up the story: “We got feedback on some of the mics, because our sound engineer was trying to get the orchestra loud enough to be heard over the band in the Albert Hall. That was a challenge in itself because sound systems were not that good in those days. But when we were listening back to the orchestra’s recorded parts, you could hear two brass players chatting while the music was going on and they didn’t have anything to do.

“They’d be saying, ‘Are you going down the pub afterwards?’ and ‘How much longer is this going to go on for?’ It just seemed to be the French horns. They were also quite out of tune and there were squeaks. We had to replace them, and got some session chaps to come in and finish the job.”

One of the fascinating aspects of progressive rock in the 1970s is how quickly the groups developed, and along their individual paths. With Camel there was typically no grand vision or masterplan, but Latimer had at least some idea about the way he wanted the music to go.

“I came from a very pop background, loving The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Shadows and then the blues,” he explains, “and Pete had played with Them, Peter Green and Rod Stewart. So our roots were very bluesy, and yet we ended up doing this English-style music with orchestral leanings. It was quite bizarre how we found ourselves in this position.

“Initially, Pete wanted to be in more of a Santana-type band and so did I in a way, because it’s a great style of music for a guitar player. But I was adamant about interjecting some Englishness or European-ness into the music, because that’s who we are. My argument was, ‘Why do we want to sound like Santana? Santana is already there doing it.’ And if we’d gone that way, we wouldn’t have had The Snow Goose,” he laughs.

“I said, ‘Let’s stop singing in American accents, let’s draw on our childhoods.’ I was in the choir in church and loved classical music, so I liked the idea of doing something more classical, and not being too bluesy, jazzy or rocky. It was striving for something that I would call ‘English’. I was young and ambitious and that’s the way we went.”

Latimer cites the Finnish composer Sibelius as a major influence on his writing, but also Rachmaninoff and Chopin. He notes that the lengthy Lady Fantasy from Mirage was inspired by Chopin, but is clearly uncomfortable with the ‘symphonic rock’ tag often slapped on The Snow Goose.

If Camel have been so avowedly and perennially English, how does Latimer feel about the group being seen by some as honorary members of the so-called Canterbury Scene? As even the groups who were playing around that city at the start of the 70s generally deny that such a scene existed, does this make any sense to him?

“It does, because at one stage, after Pete left the band in 1978, we got in [keyboard players] Dave Sinclair and Jan Schelhaas, both from Caravan,” he replies. “So at one stage we were being called Caramel and all sorts of silly things like that. Andy Ward and I loved Caravan’s first album, so that was also an influence on us.

“I think possibly the idea came from America,” he adds, “as they didn’t realise that we were from Guildford, a hundred miles from Canterbury, or whatever, and just lumped us in with that scene.

“We also had the same producer, David Hitchcock, who produced Caravan and Genesis. We asked him to do it, because we liked both of those bands. So there is a connection with the Canterbury Scene although none of us is from Canterbury.”

Although Latimer doesn’t think there is an overt musical connection, he recognises that Camel and Caravan sometimes shared a similar melodic, swinging, freewheeling aspect to their music: “There weren’t that many bands around doing that stuff, so you tended to bounce off each other. The same with them – they probably listened to us.”

In common with many of the Canterbury bands such as Caravan, Hatfield And The North and Soft Machine, Camel concentrated more on the instrumental side of their music. Looking back now, Camel had two perfectly capable vocalists in Latimer and Bardens. But in the days of star lead singers such as Mick Jagger and Robert Plant, both men were a little diffident about their abilities. But then, fortuitously, their attitude set them on the path that led them to make Camel’s most famous album, and one that still sounds fresh 40 years down the line.

“We weren’t a strong band vocally and so we tended to bury them and have lots of effects on them, and use the voices more as instruments,” admits Latimer. “We largely considered ourselves an instrumental band with some vocals, so it was the natural course to do a whole instrumental album like The Snow Goose.

“We didn’t know if it would sell or not as Camel have never been an easy band to sell,” he concludes. “I remember going to New York to see the American company who were putting it out and telling them that it was one piece of music, all instrumental and they just went white: ‘Oh my God, how are we gonna sell this?’”

America didn’t understand, but Europe and the UK did. Camel’s breakthrough album was followed by 1976’s similarly airy Moonmadness (which reached No 15 in Britain) and Peter Bardens’ last Camel album, 1978’s jazzier Top 20 hit, Rain Dances.

“Back in the 70s I had an idea after The Snow Goose of where we were going musically,” concludes Latimer. “So I was always pushing us in areas in which I thought we should go. I’m always pushing to do something unexpected. Ultimately, The Snow Goose was the album that put Camel on the map.”

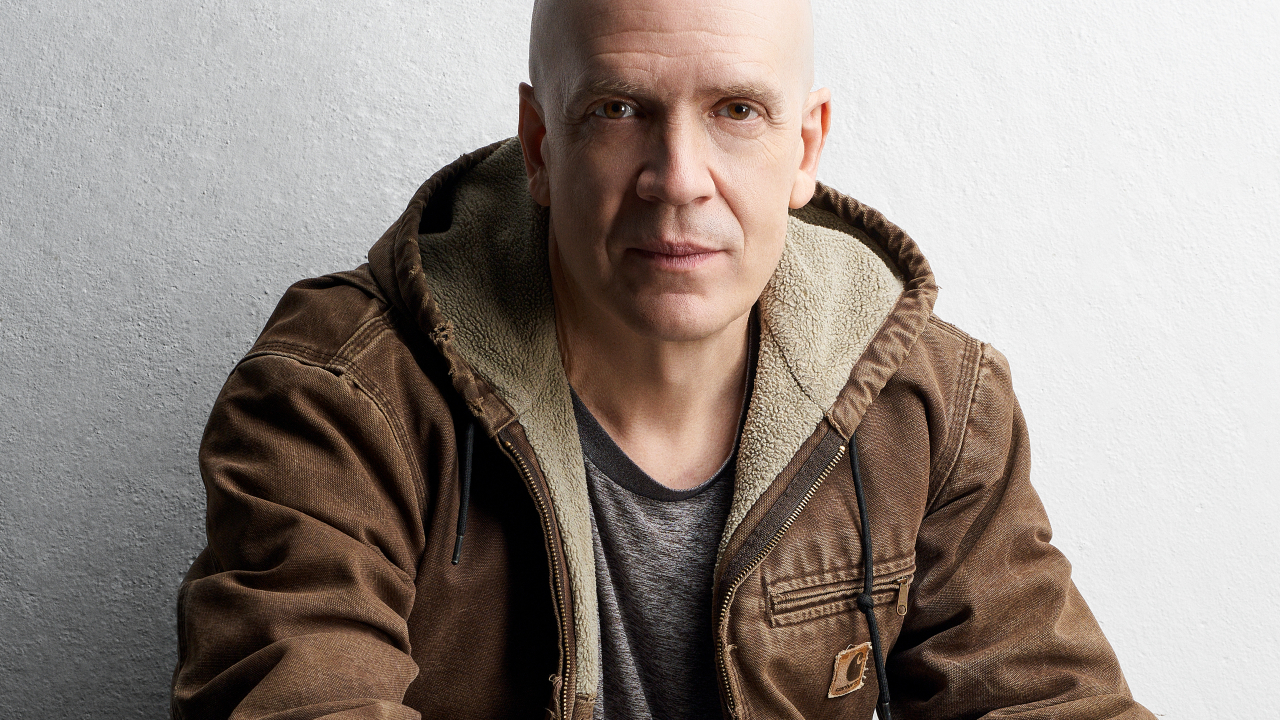

Stationary traveller: Camel’s Andy Latimer, shot exclusively for Prog, Salisbury, March 2015.

Why I Love The Snow Goose… by Messenger’s Khaled Lowe

This is one of my favourite concept albums by one of my all-time favourite bands. What I find particularly enthralling is the fact that an exclusively instrumental record can convey such a range of emotions.

Essentially it’s a love story: a tale of kindness and of honour set against the backdrop of the Second World War. When Rhayader dies during the evacuation of Dunkirk but is visited by the Snow Goose in the midst of the battle, it’s a symbolic gesture that even during one’s darkest hour, hope can still prevail. It’s a beautiful narrative about the prevalence of optimism during times of strife, conveyed by a unique relationship between a bird and two humans. It’s a very poignant and emotive theme to base an album on.

Sonically, what a tour-de-force! From the samples of birdsong and the flapping of wings used in The Great Marsh (created by bassist Doug Ferguson waving his coat around in the studio!) to the classical flourishes of Rhayader Alone, to the delightful acoustic ambience of Sanctuary and the proto-metallic chaos of Dunkirk, this album has it all: spiralling sonic soundscapes, dense instrumentation, powerful and dramatic arrangements, and, of course, the soul-stirring guitar of Andrew Latimer.

All these facets combined make one of the best records to have ever come out of the progressive rock genre, in my humble opinion. One that explores the entire gamut of human emotions in all its complex brilliance. Their performance at the Barbican in 2013 was one of the most epic performances I’ve ever attended by any artist.

Why I Love The Snow Goose… by Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt

Mike Barnes is the author of Captain Beefheart - The Biography (Omnibus Press, 2011) and A New Day Yesterday: UK Progressive Rock & the 1970s (2020). He was a regular contributor to Select magazine and his work regularly appears in Prog, Mojo and Wire. He also plays the drums.