“When I listen to Sheik Yerbouti and Joe’s Garage, it reminds me of what a giant he was." Frank Zappa's incredibly busy and industrious 1979

Terry Bozzio and Adrian Belew look back on the year Frank Zappa created Baby Snakes, Sheik Yerbouti, Joe's Garage and more

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of Sheik Yerbouti and Joe's Garage, in 2019 Prog's Malcolm Dome spoke to drummer Terry Bozzio and guitarist Adrian Belew about one of Frank Zappa's buseit years ever!

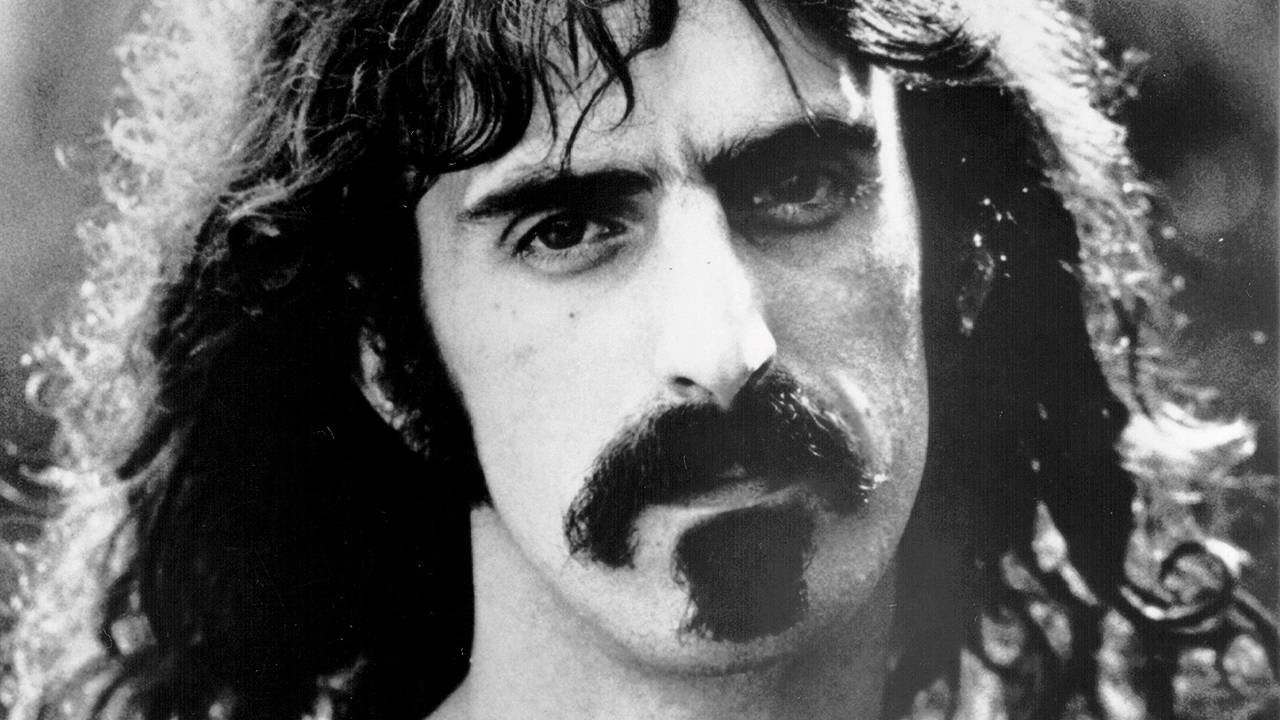

To call Frank Zappa prolific is hardly an illuminating comment. But even by his remarkable standards, what he did in 1979 was impressive: the man not only released five albums, but also a movie.

“Frank really was a workaholic,” recalls guitarist Adrian Belew. “He never seemed to stop. That was one of his defining traits. Apart, of course, from being a genius.”

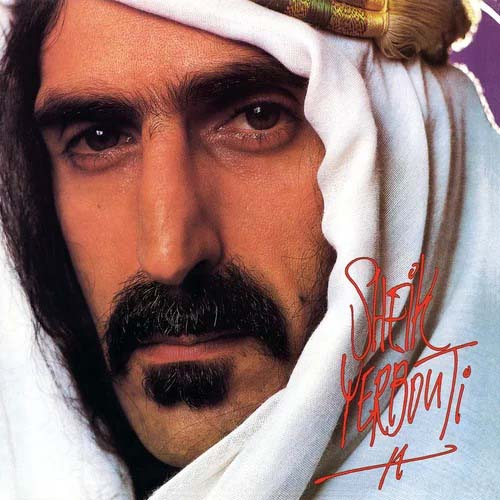

It must be pointed out that two of these albums, Sleep Dirt and Orchestral Favorites, were actually released without his permission. This happened during a legal dispute between Zappa and Warner Brothers. As the label already had the tapes for these albums, as well as Studio Tan (which came out in September 1978), they went ahead and put them out, claiming that they had every right under the existing contractual agreement. Eventually, Zappa was able to leave Warners and set up Zappa Records, with distribution through Phonogram, leading to the release of Sheik Yerbouti in March ’79.

This double album featured live recordings which were then expanded and enhanced in the studio.

“I had left Frank’s band by the time that he took the tapes into the studio,” remembers Belew, “so I was only involved in what was done live. Now, most of the people who played with Frank could read music, but I couldn’t. The way I learnt my parts was by following him around for three months, while he taught me what I needed to know, and how the material all worked. It was very painstaking, but worth it.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“This was typical of Frank,” Belew continues. “He mapped everything out, and knew exactly what was needed from all of us. Frank left nothing to chance, and didn’t leave any musician room to add his own motifs. He wrote it all down, and expected it to be followed to the note. Not only that, but he wouldn’t tolerate any mistakes when you came to perform it onstage.”

“Drummers got a lot more freedom than any other musicians who worked with Frank,” says drummer Terry Bozzio. “There were times when he’d tell me exactly the way he wanted something played, and that was a little ego bruising. But on a lot of occasions, he’d let me do what I felt worked best.”

Belew reveals that much of Sheik Yerbouti actually came from soundcheck recordings.

“Frank was one of these people who really enjoyed the whole process of doing soundchecks. They could last for a couple of hours, and he’d record them as well. That’s where a lot of what you hear on the album comes from. And this is where I got to do my parts.

“I was also lucky in that I could sing in a wide range of differing styles, and you can hear what I can do on Sheik Yerbouti. I did the vocals for Flakes, where I was asked to do something in a Bob Dylan style. I was also able to play some lead guitar parts here, because Frank needed someone to cover him in this area while he was doing other stuff.

“Frank was also keen to emphasise the comedic nature of his lyricism on this record, and that suited what I was doing. The thing with him was always that he looked for ways to explore different aspects of life, and he believed that through laughter he could get people’s attention and make them think. It’s also why he never believed anything was fully finished. So, while for a lot of artists recording something live was the be all and end all, for Frank it was only the start.”

However, Belew wasn’t able to follow this through by being in the studio when Zappa added this dimension to the album,

“The problem was that by then, Frank was also involved in editing the Baby Snakes film. He told me this could take him three or four months to do. I had just been offered the chance to tour with David Bowie, so I talked to him about this. He had a choice, really: either to let me go out with Bowie, or else to pay me to sit around doing nothing while he worked on Baby Snakes. It wasn’t hard to understand why he allowed me to leave for Bowie. I can’t say he was happy at losing his guitarist, but to be fair he never bore me a grudge, and we remained on very good terms. In fact, I always thought I might one day return to his band, but never did.

“Mind you, I do recall that when Bowie told Frank that he thought I was a good guitarist, the response was, ‘Fuck you, Captain Tom!’ That was typical of him. He even managed to demote David from being a major in a reference to Space Oddity!”

“The thing with Frank was that he always looked for ways to develop what was already recorded,” says Bozzio. “So, we did live recordings for Sheik Yerbouti and he then took these into the studio to add what he felt was necessary to make it all work.”

Zappa painstakingly used the studio to develop the sounds that had been recorded live for Sheik Yerbouti. Belew has enormous admiration for what he achieved.

“I knew he was planning on going into the studio with what he had, but never had a clue what he had in mind. However, I spent so much time with him while I was with the band that I got an insight into the way he could use studio technology to shape a sonic marvel. I also saw this in the way that he built his home studio [Utility Muffin Research Kitchen]. When I first saw this, it was really no more than an empty room. But Frank painstakingly created something brilliant.”

To this day, the guitarist is proud of the album.

“I know this is the best-selling record Frank had, and the fact it was on his own label made it especially satisfying for him. I can listen back now and know I was involved in something special. What Frank rarely ever did was invite the musicians in the band to share his inner thoughts. On many occasions, I sat next to him on flights, while he worked away making notes. At first I always tried to lean over and find out what he was doing, but I soon learnt that he didn’t appreciate that sort of attention and left him to it. Frank liked to keep his thoughts private until they were fully formed. He was a person who was always having notions about where to take his art, and because it was very much his creativity that he was organising, I don’t believe he felt having other people to bounce things off was the least bit helpful. On the contrary, it would have confused what he was trying to get into focus.”

However, the process of putting together the Sheik Yerbouti album was almost overshadowed by the ongoing legal battle between Zappa and Warner Brothers, as Bozzio remembers.

“Patrick [O’Hearn, bassist and vocalist] and I would spend time in Frank’s basement back then, which was in the early stages of him putting together his studio. This was as Frank worked on the album. And he told us that because of all the legal problems he was up against he was running out of money, therefore may not be able to pay us. He wanted to be straight with the two of us about how bad his financial state was, due to the lawsuit. But we both told him we had enough money saved up, thanks to what he’d already paid us, that we were prepared to carry on being a part of the band until he could afford again to resume payments. It is important to stress that all of us who were lucky enough to be in Frank’s band felt we owed him a debt. Through being involved with him our reputations were massively enhanced, and we got opportunities which would have been denied otherwise. So, there was a strict sense of loyalty there. Frank was always straight with us, but to desert him at such a time would have been appalling, even if he’d have understood.

“Thankfully, things never reached the stage where Frank actually went broke. But I think that tells you of the loyalty he inspired in all of us. We owed the man so much, and being in his band was a privilege. I wish that I could play with him now, because I have the experience and maturity to appreciate it more than I did at the time. Being a young musician I couldn’t fully get to grips with the way he was pioneering so much stuff – it was way above my head.”

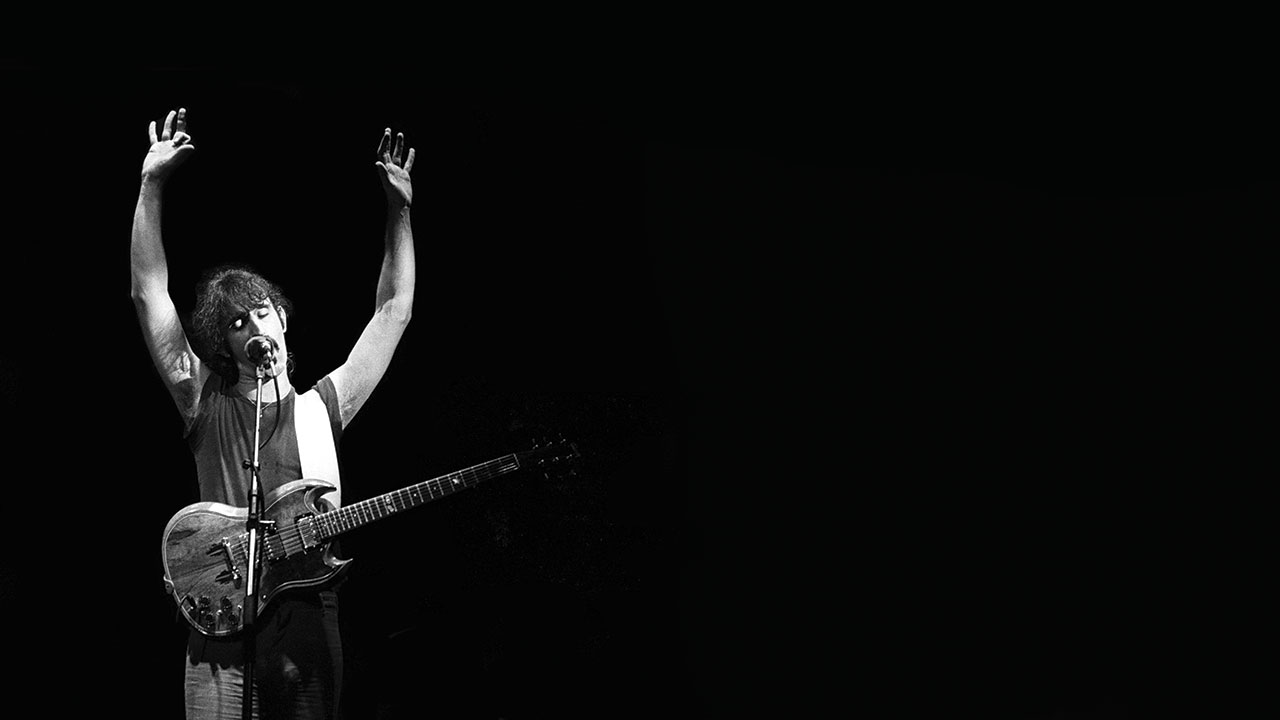

Belew vividly recalls being involved in the early stages of Baby Snakes.

“We did five shows in New York during the Halloween period in ’77.”

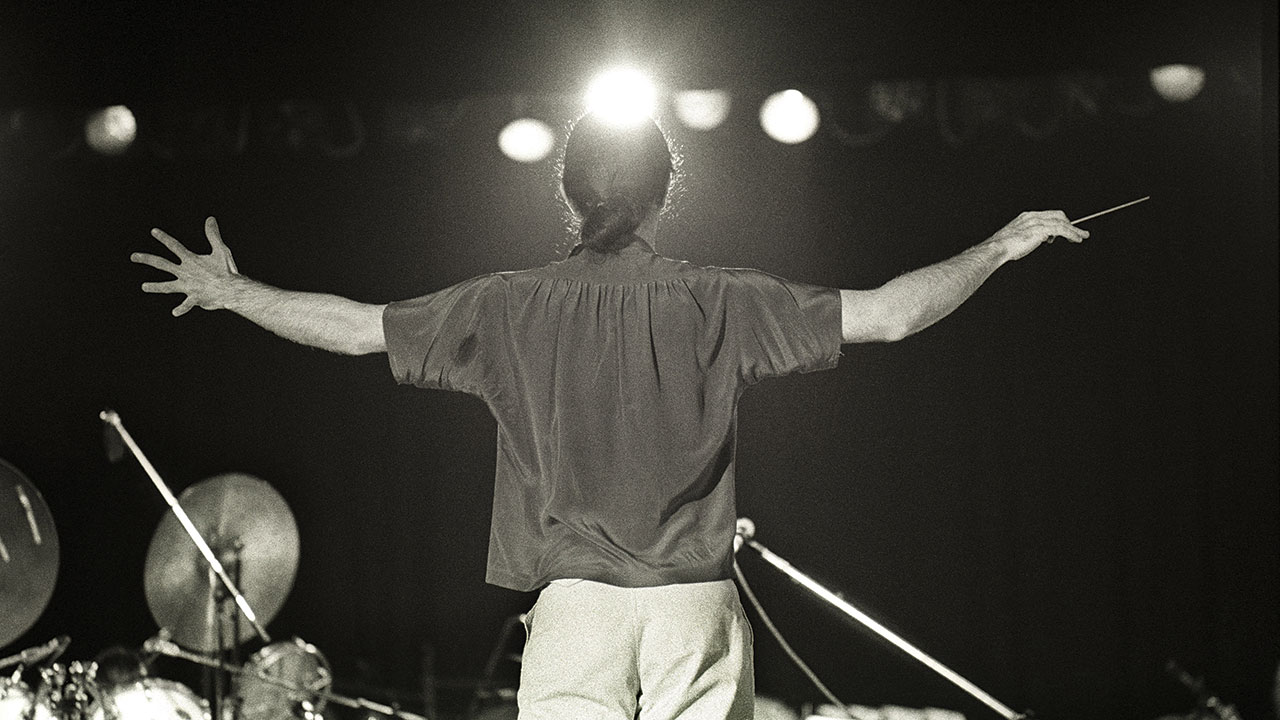

These were all at The Palladium, where the shows were not only recorded but also filmed.

“All of us were encouraged to be very theatrical and to dress up; I know I wore a dress, which was fun. He also shot what was happening backstage. Again, none of us really knew what he had in mind. But it was always going to be different.”

Finally, Zappa added stop motion clay animation to the existing footage, to create a movie that was surreal, bold and very much typical of Zappa’s unique vision and artistry. However, he struggled to find a distributor for what was a film close to a running time of three hours.

“I watched it all… eventually,” laughs Belew. “This was just so long that it was tough to sit through the whole thing in one go! But I have to say I was impressed.”

“I don’t think Frank told anyone in the band what he was planning to do with the footage,” says Bozzio. “But that was what usually happened with him. He always had these grandiose plans, such as Broadway plays, and most of them never came to fruition for one reason or another. So, he might have mentioned using clay animation, however we probably never took any notice. It was his vision, after all, and we were lucky to have a role in it. Frank had these ideas which would’ve seemed utterly insane to any ‘right-thinking’ people. Baby Snakes was one of these. That’s why no one would put up the money for it. Now, a lot of artists would have scrapped the whole thing due to lack of outside finance. But Frank took it as a challenge, and wanted to show all those who’d refused to back him that he was right, and this could sell.”

Zappa cut it down to 90 minutes, and put it out himself through his own production company, Intercontinental Absurdities. It came out in December ’79, being shown for 24 hours a day at the Victoria Theater in New York, making a significant profit. Zappa also made the original version available by mail order until the mid 90s; it was released on DVD by Eagle Vision in 2003. The soundtrack album came out in 1983.

The man himself once said of Baby Snakes: “It’s a movie about people who do stuff that’s not normal. Without deviation, progress is not possible. Normal people should see Baby Snakes, so they can find out what they’ve been missing.”

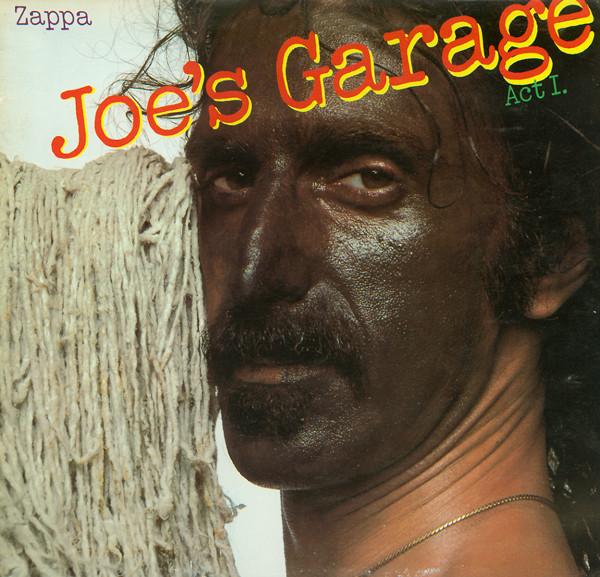

For his Joe’s Garage rock opera, Zappa set his sights on targeting the music industry, censorship, American politics, organised religion and sexual mores. The three-act masterpiece used an enriched satire rather than a stiflingly serious negativity, and in doing so was very effective and affecting.

Bozzio was cast in the role of a character called Bald-Headed John, but he never contributed any drum parts to the album. These were all handled by Vinnie Colaiuta.

“By the time Joe’s Garage was being done, I had left to join UK,” reveals Bozzio. “So Vinnie was already really settled in the band, and there was no room for me to play the drums. And Vinnie was just so good anyway, why did Frank need me? The reason I got to play Bald-Headed John was because I used to regularly stop by Frank's place to say hi. I still got on very well with him. One day, he thrust this script in my hands and told me to go into the studio and read these lines for a character in something he was working on. That was typical of him – get anyone who happened to be around to participate. I had no clue what this was for. I just did what I always did with him and followed orders!”

One thing Joe’s Garage is noted for is the use of xenochrony. This was a technique that Zappa himself originated in the 1960s, wherein he’d take an instrumental part from an older recording and overdub it into a new recording.

“Frank was brilliant at doing this,” says an admiring Bozzio. “He had such an amazing memory that he could recall something he’d done in the 60s and know a drum or guitar part from that would work in a new setting. He had what I’d say was a collage approach to music. He was also great at improvisations based on no more than a half-formed idea someone has, which was the case with Punky’s Whips (from the 1977 album Zappa In New York). I had this fascination with the image of Punky Meadows, the guitarist with a band called Angel; I’d seen a photo of him in a magazine. I told Frank, and he turned it into a tremendous song, though allowed all musicians to be spontaneous, but in a disciplined way that was unique to him. I know he used the same approach on Joe’s Garage.”

The album was released on two separate albums. Act I came out in September 1979, with Acts II & III released two months later. It was only in 1987 that the three were put together in a three-LP box and also on two CDs.

For Zappa, 1979 was a crossroads year. Not only did he release three landmark works in Baby Snakes, Sheik Yerbouti and Joe’s Garage, but he also completed his own studio and started a label. To some artists that would be sufficient to define an entire career. But since when was Frank Zappa ever ‘some artist’?!

“I owe my career to Frank,” insists Bozzio. “When I listen to Sheik Yerbouti and Joe’s Garage, it reminds me of what a giant he was. Nobody else could have conceived these works, let alone recorded them. Frank was unique, and opened my eyes and ears to so much when it came to music. He understood how to remove limitations, which is why he could dip into any genre from classical to jazz, pop, metal, electronic and give it his own twist. I suppose that is what you call ‘genius’.”

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.