"The fallout was much bigger than anything we could ever have foreseen": Dire Straits and the adventure of Brothers In Arms

Everything changed for Dire Straits when they made Brothers In Arms: Mark Knopfler, John Illsley and Guy Fletcher look back

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It’s spring 1985 in Britain. The coal miners have ended a rancorous, year-long dispute with Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. In the wake of the Heysel Stadium riot, in which 39 people died and 600 were injured, English football clubs are banned indefinitely from competing in Europe. Coca-Cola is fanfaring its New Coke brand into supermarkets – it will last a mere three months of going unloved and undrunk before being abandoned ignominiously by the company. The latest James Bond film, A View To A Kill, Roger Moore’s final time as 007, is in cinemas, and the Beeb’s new soap opera EastEnders is airing twice weekly on TV.

In 1985, as a nation we still have the choice of just four TV channels. No one has a mobile phone or access to the internet. But one new device is offering to the masses the promise of a gleaming new age: Philips’s CD150 is the first budget-priced CD player to be launched onto Britain’s high streets, and by the end of the summer it will be synonymous with nothing as much as with Mark Knopfler’s wry, doleful voice and the sound of his guitar.

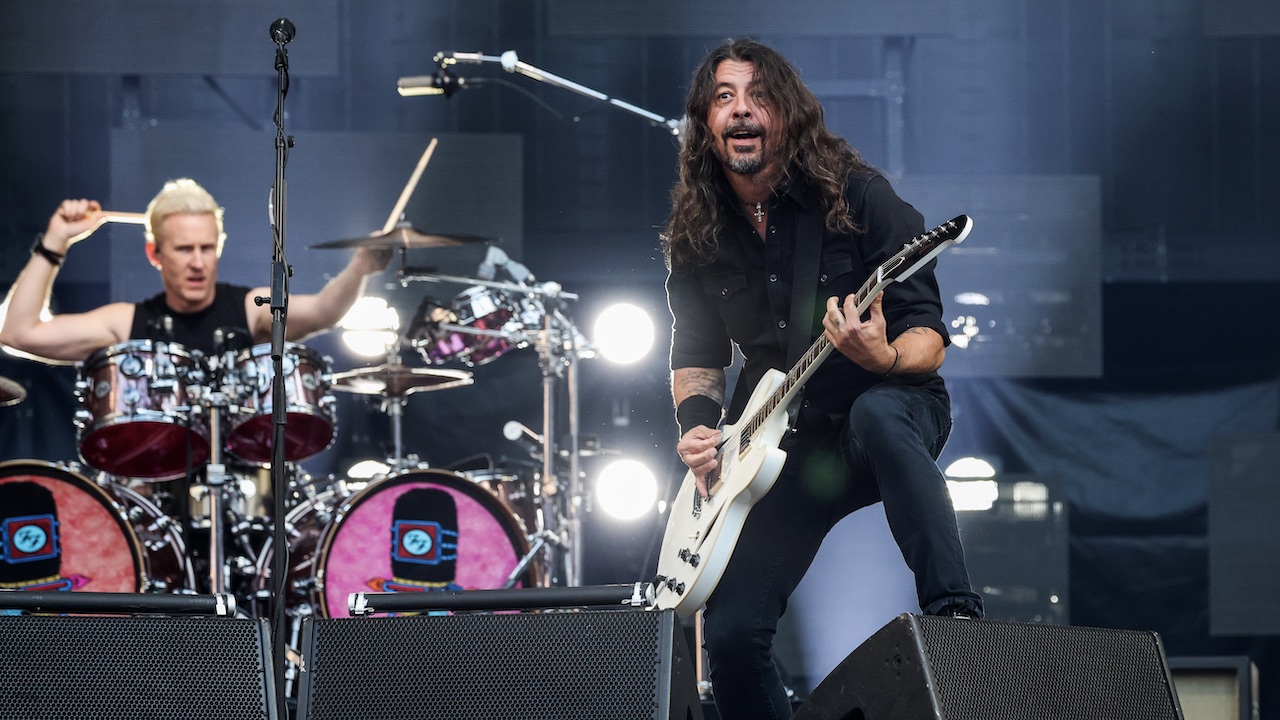

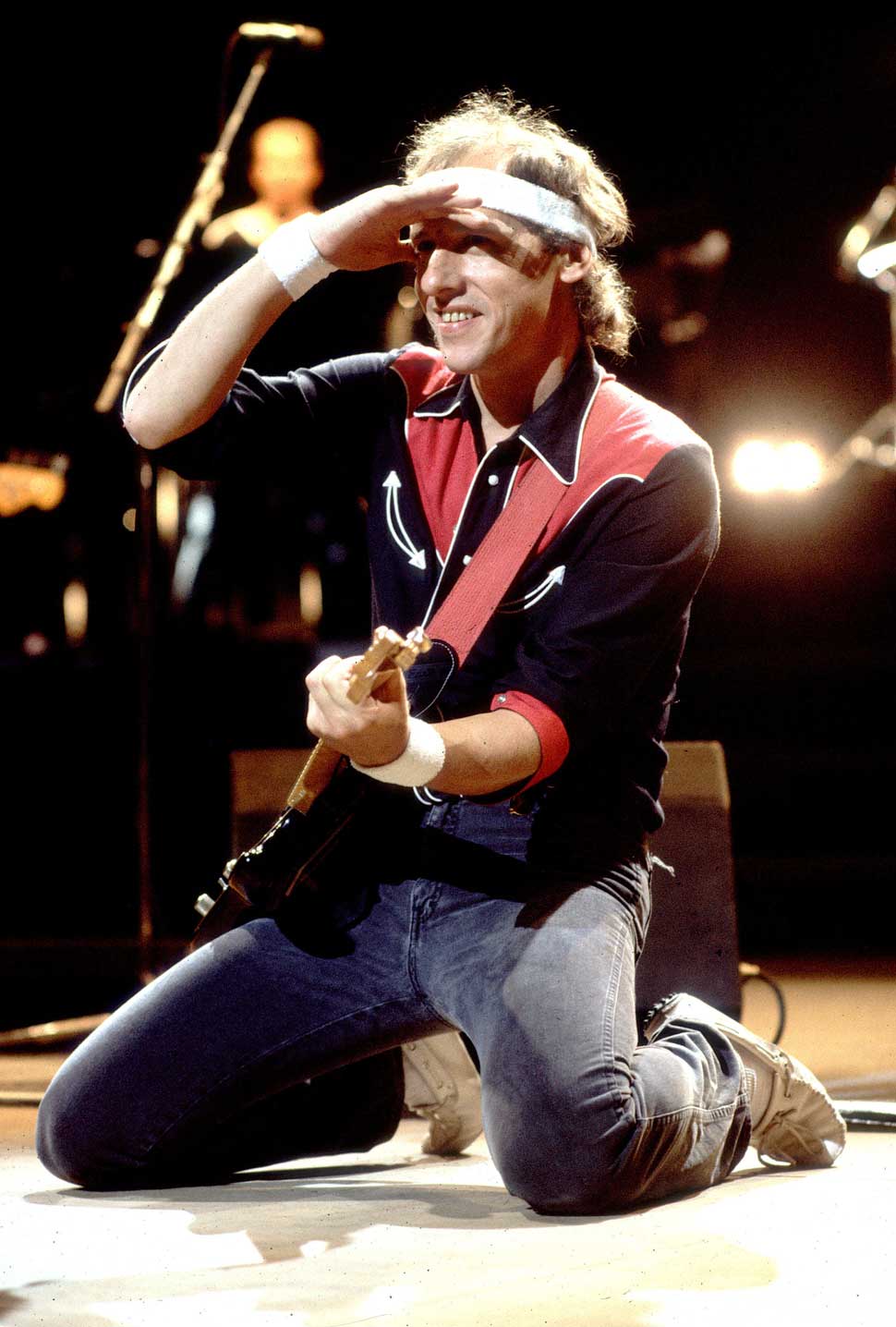

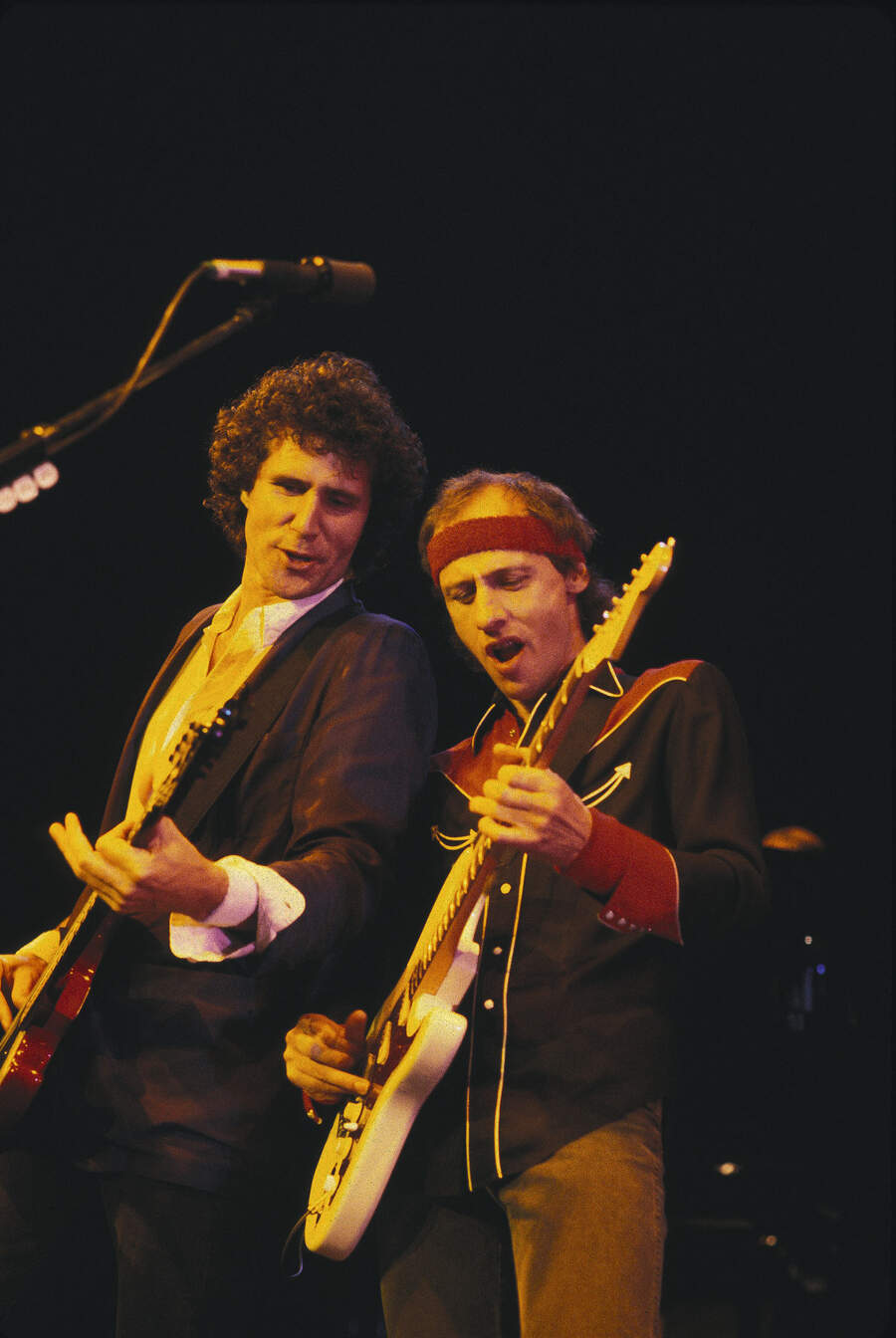

Released on May 17, 1985, Brothers In Arms is Knopfler’s band Dire Straits’ fifth album. In the seven years since bursting out from the South London pub circuit with Sultans Of Swing, a rollicking love letter to a fictitious jobbing pub band, the Straits have built a robustly loyal following on the back of Knopfler’s tunefully literate songs and near-constant touring. Brothers In Arms, though, is a whole other deal. In short order, it will make superstars of the balding, headband-sporting Knopfler and his bandmates.

Happenstance is very good to them. Philips hold the majority share in the Straits’ record company, Polygram, and Knopfler’s co-producer, New Yorker Neil Dorfsman, cajoled him into making Brothers In Arms one of the first records recorded to 24-track digital tape. What better way to push a music player touted to be sound-enhancing than with a record actually designed to be sonically pristine? Ergo, wherever a CD150 is to be found, right there alongside it will be a CD copy of Brothers In Arms.

This much accounts for the fact that the album fast becomes the first record to sell a million copies on CD. Its other 30 million-plus sales can be attributed to several other factors, among them the band’s sortie to a Caribbean island, Sting’s trilling of the line ‘I want my MTV’ on a track, the onset of another technology, video animation, and the globe-spanning Live Aid concert. Yet for the most part it boils down to the simple fact that nine of Knopfler’s songs prove to be so universally irresistible, and a band hitting their peak.

“It was a remarkable thing to have been involved with,” John Illsley, Dire Straits’ onetime bass player and Knopfler’s chief lieutenant in the band, says today. “A wonderful memory, all things being considered, and happy endings.”

For Knopfler’s part, he offers a shrug, a hangdog smile, and says with what proves to be a typical absence of pretence: “It’s not very complicated. It was just a bunch of luck, really. I do remember it being a fantastic time. It was what we all wanted and had been chasing. I suppose you could also say the fallout was much bigger than anything we could ever have foreseen.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

To mark its 40th anniversary this year, Brothers In Arms was re-released once more, in deluxe CD and old-school vinyl formats, with the addition of a full-show recording from San Antonio, Texas on night 91 of the Brothers tour. Enough for Knopfler, Illsley and Guy Fletcher, the latter brought into the band on keyboards for the Brothers sessions, to gather at three different locations in April to look back: Knopfler in his West London studio, Illsley at his holiday home in Portugal, and Fletcher in the sun-dappled living room of his house on the English south coast.

Occasional golf partners and near-neighbours, Illsley and Fletcher are model English gentleman rock stars, chatty, disarming, self-deprecating. Illsley claims not to know of the San Antonio recording’s existence, much less to have heard it. “But then people often don’t tell me about these things,” he says with a sigh.

Knopfler is ever so softly spoken, humbleness personified. He is prone to shuffling off topic and has the air of a kindly handyman who’s popped round to mend a leak. But it makes him difficult to pin down, and which is likely the point. As the Straits’ long-serving manager Ed Bicknell told me back in 2015: “Mark is the master of vagueness.” Knopfler lights up the most when referencing his beloved Newcastle United’s recent winning of a long-overdue trophy, the Carabou Cup, in March. “A lifetime of waiting,” he says, glowing with the enthusiasm of a 75-year-old schoolboy.

He and Illsley first met in 1976. Illsley was sharing a council flat in London with Knopfler’s younger brother David. He found Mark crashed out on their living room floor one morning. Soon enough they’d formed a band together playing Mark’s songs, with David Knopfler on rhythm guitar and Pick Withers, a North London habituate, on drums. Withers, jobless at the time, suggested the name Dire Straits.

Their self-titled debut album of 1978 was driven along by Knopfler’s knack for folksy melody and a classic rock-minted tune. The following year’s Communiqué was more of the same, then they raised their game with 1980’s Making Movies. On that album, Knopfler stretched out on such finely sketched songs as Romeo And Juliet and Tunnel Of Love. He also had an explosive argument in the studio with his brother, who promptly quit.

As if freed from shackles, Knopfler progressed the band still further on 1982’s Love Over Gold, an album of just five songs, with the 14-minute-plus Telegraph Road and Private Investigations navigating a territory between Bruce Springsteen’s heartland rock and Bob Dylan’s regal mid-70s. Withers bailed after they’d made that record, leaving Knopfler and Illsley to soldier on with keyboard player Alan Clark. According to Ed Bicknell again, Knopfler possessed a determined streak and was “quite ruthless. That’s not a criticism, by the way. If you’re going to climb the greasy poll, you need to be ruthless”.

“Apart from the fact Mark was a humble man,” says Illsley, “and he didn’t really take himself too seriously, I think he saw himself more as a songwriter who played the guitar. Songwriting to him is more significant. He played the guitar in sympathy with the song, and that’s what we did as a band when we joined in. But keep in mind, if you’re the guy that wrote the song, you really have to be solely responsible at the end of the day for saying: ‘That’s it.’ To me, that’s what ran through the whole of the Dire Straits lifeline.”

“When I started, I was too good at telling other people what to do,” Knopfler avers. “Once I started playing with more practised and experienced, toplevel people, I realised I didn’t have to do that.”

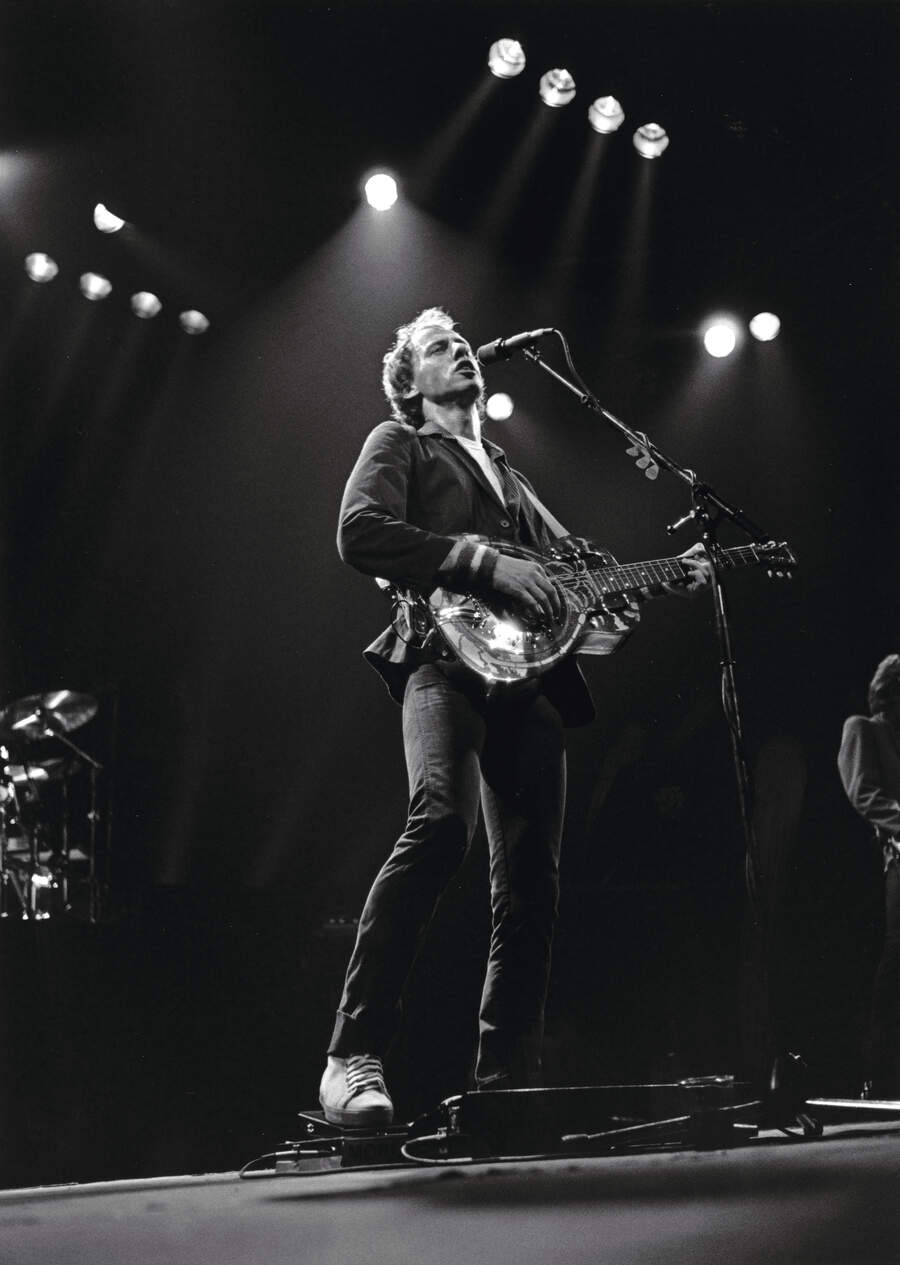

Knopfler was himself fêted, a single sustained note enough to identify the signature sound of his guitar. Dylan was admirer, and invited Knopfler to play on his 1979 album Slow Train Coming and produce 1983’s Infidels.

After Love Over Gold, Knopfler branched out into doing film soundtracks. First Bill Forsyth’s charming Scottish comedy Local Hero, and after that an Irish Troubles drama, Cal, and Forsyth’s next film, Comfort And Joy. To better enable him to write and record at home in West London, he bought an early synthesiser-sampler, a Synclavier, but couldn’t get it to work. Enter technical whizz Guy Fletcher, just off touring with Roxy Music.

“Mark had a mews house in Holland Park at the time,” says Fletcher. “I literally knocked on his door with a keyboard under my arm. The Synclavier was ridiculously expensive and very high-tech, and he needed someone to help him out with it. He played me a load of music he loved – a lot of JJ Cale, a bit of Dylan – and we hit it off.

“Neither of us is a trained musician. Our upbringing is based on what we were listening to, and it’s all done by ear. First impressions? How intense he was, how deep in thought, how meticulous. A million ideas a minute. He had a vision for everything he wrote, and he was very intent on achieving it.”

Parallel to his extra-curricular projects, Knopfler was writing songs for Dire Straits’ next album, taking scraps of ideas he’d assembled on the road and fleshing them out back at home base. The source of one song, Walk Of Life, was a record he’d been listening to of Cajun folk music. The title of another, Brothers In Arms, was spoken by his architect father in a conversation they’d had about the Falklands War.

More often than not, the lyrics came to him first. Famously, he picked up those for Money For Nothing from a conversation he overheard in a Manhattan electrical store: a loud-mouthed delivery man, leaning over his trolley, holding court to the store junior about the fecklessness of modern musicians.

“All the possibilities were there in that song, and that’s a thrill,” Knopfler says. “I just hid behind a stack of microwaves and listened in, because every next line was better than the last. This bone-headed guy would say things like: ‘What’s that, Hawaiian noises?’ He actually said: ‘That motherfucker has got his own jet airplane.’ That’s how he spoke, which I didn’t put in the song. “After the guy had left, I had to ask for a pen and paper from the woman at reception. Then I sat down in the kitchen display area, in the front window of the store, and wrote down all these lines from memory.”

Knopfler says he had a facility with language from an early age. Always a voracious reader, he took Steinbeck to his bed when he was off sick from school – “nine years old, not really understanding it but fascinated”. One summer’s day in 1985, he asked Bicknell to have the band reconvene. Illsley, Clark and the newly enlisted Fletcher were summoned to the Holland Park mews to hear Knopfler’s fresh batch of songs.

With Love Over Gold tour drummer Terry Williams completing the line-up, they went into Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera’s Galley Studios in leafy Chertsey in Surrey to rehearse them. Collectively, they were a mixed bag of songs, ranging from something as knockabout as Walk Of Life to the harder-edged The Man’s Too Strong and the woozy, late-night confection Your Latest Trick.

According to Knopfler, he carried a torch for Money For Nothing right off the bat (“I knew it was going to be fun”). Fletcher was taken by the simmering Ride Across The River, while the quietly brooding title track struck each of them as a substantial piece.

“All the time we worked on it, I felt it was going to be a song that resonated,” says Illsley. “And I wasn’t wrong. Every time I played it then, and whenever I do now, I get a shiver down my spine. It was the moment with the album where I thought we were doing something different to anything we’d done before.”

Knopfler says it was the song he spent the longest on. “Because it’s quite deceptive. Each verse is slightly different from the one preceding it. These little variations are built into the song. I’ve heard classically trained musicians make the mistake of playing it straight. You have to listen hard to figure out what’s different from the third verse to the second, and the second to the first. It might be just one ‘blue’ note, but it changes the way you feel.”

His lack of formal training, he reflects, likely made him less bound to the established rules and conventions of writing music. “I would just stagger from one place to the next,” he says. “I’m sure a structured education, enrolling at Juilliard, say, is a wonderful thing, but mine came from hearing Lonnie Donegan play Leadbelly songs, and up through The Shadows. You just go marching out into the middle of the thing, not really knowing what you’re doing. Innocence is bliss.”

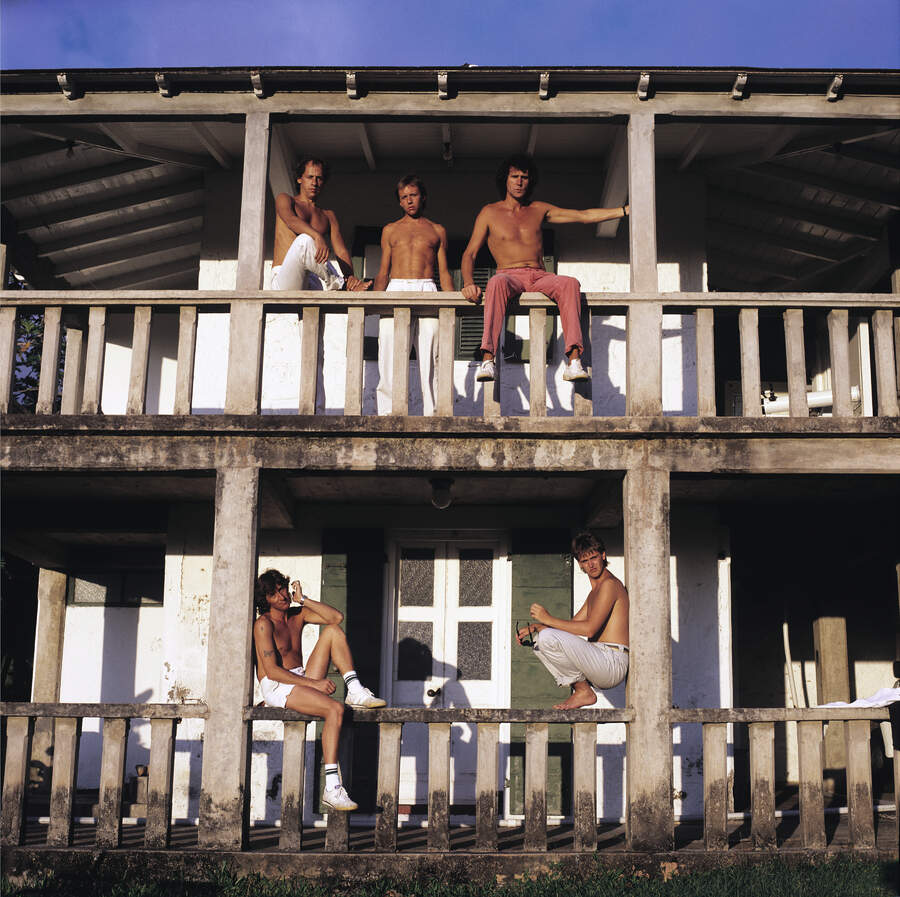

When it came to choosing where to record the album, one option stood out. In 1979, George Martin, The Beatles’ producer, had opened a branch of his AIR Studios on the tiny Caribbean island of Montserrat. Both Knopfler and Illsley had got to know the urbane Martin, who suggested they follow The Police and Eric Clapton’s footsteps out to Montserrat and record there. Neither man needed too much persuading.

In most aspects, Martin’s place was idyllic. Serene, detached, the white-walled, plantation-style studio and accommodation building faced out to a swimming pool, and beyond it the aquamarine ocean. There was a watering hole, Andy’s Bar, on site for the visiting artists to patronise. In the evening they could unwind outdoors, dining on freshly barbequed fish rustled up by the resident chef, a garrulous, outsized man known to one and all as Daddy George.

On the other hand, the sheer remoteness of the location made other basic practicalities a challenge. Two of the delicate Sony digital tape machines ordered by producer/engineer Neil Dorfsman had to be transported to the studio on the back of a pick-up truck, over potholed track roads, with a couple of local labourers assigned to hang on to each lest it go bouncing off into the bush.

The weather, too, was prone to extremes. Four years later, Hurricane Hugo reduced AIR to rubble. The Dire Straits party arrived in November, and into the jaws of the storm season. It rained relentlessly the first six weeks they were there. There was literally nothing else for them to do but record. Dorfsman, who’d cut his teeth on Making Movies and Love Over Gold, got to grips with the nascent digital technology.

“Every day, we got up, had breakfast together, and then we were in the studio from ten a.m. to ten p.m.,” says Illsley. “We’d arrived there pretty organised, so there was quite a lot we were able to get done.”

“It was an interesting period with the digital recording,” says Knopfler. “An adventure as well. Neil was chasing after what he ruefully refers to now as ‘perfection’, which is not something you can actually get, but he’d learnt his craft. He was a tremendous engineer. I used to just sit and watch him work, taking it all in, and he couldn’t tell me to clear me off because it was my record.”

They broke off to spend Christmas at home in England, then returned to Montserrat in early January 1985.

The second round of sessions got off to an inauspicious start. There were technical issues with the Sony machines, the extent of which the principals disagree on. Fletcher’s version of events has it that a bad batch of tape caused them to lose just one of the songs they’d recorded on their first visit. Illsley insists that everything they’d originally recorded was erased and the band “kind of having to start all over again”.

What isn’t in doubt is that drummer Terry Williams had struggled with his requirement to play to a click track, and was relieved of his duties. In his place came American session ace Omar Hakim, just off having played on Sting’s solo debut album The Dream Of The Blue Turtles, and at Knopfler’s behest.

“Mark was always looking for something different,” says Fletcher. “Some other element that wasn’t in the room. I do remember watching Omar set his drums up, how he’d play rhythms while he was tuning, and I’d never seen anything like it. There were some heavy chops going on.”

The departed Williams had at least left behind one thunderous volley. He’d put it down as an intro part to Money For Nothing, Knopfler’s intended centrepiece song for the album. The track otherwise was proving to be a headache, never quite right whichever way they came at it, and to the point, says Fletcher, that Knopfler had begun to lose interest in it.

Over dinner one night, Dorfsman collared Fletcher and encouraged him to try a synth part on the song. Or, in Fletcher’s translation, “to give it a sound like a dinosaur. I thought of it more as a crashing sound. Anyway, I threw it down there and then on my Yamaha DX1. The track was scheduled for the bin, but when the band heard it the next morning it renewed everyone’s excitement in it”.

From there, simple good fortune intervened. In the first instance, Knopfler was also grappling to find the exact guitar sound he wanted for the track. He was especially taken with the molasses-thick, fuzzy tone Billy Gibbons stirred on ZZ Top’s Eliminator album of two years previous, but hadn’t been able to replicate it just so.

In the event, a rogue mic put him right. As Knopfler was taking yet another pass at the part, a guitar mic drooped from a speaker cabinet towards the floor. Presto, he found himself playing a near-identical version of Gibbons’s chugga-chugga boogie.

“One of the assistants spotted the mic and went to move it,” says Fletcher, “and everybody shouted at once: ‘No! Don’t touch it!’ Once Mark had his guitar lick down, the whole song took off and became its own lifeform.”

The final flourish, Sting’s beseeching backing vocal, was also an accident of fate. Knopfler was thinking about a promo spot The Police had done for MTV, and it being sung to the hook melody of one of their biggest hits, Don’t Stand So Close To Me. Over a band lunch one day, he speculated on how Money For Nothing might be elevated by Sting’s presence on it.

“And one of the lads piped up: ‘He’s just down the road from here, along the beach, on his holiday,’” he says. “I mean, we’re on this speck in the middle of the ocean. So Sting came up one afternoon and sang his part for us. It did feel like a blessed sequence of happenings.”

Your Latest Trick, another song they’d butted heads at, also fell into place. On this occasion, a visiting Ed Bicknell was the chief instigator. Knopfler envisaged the song as a bebop jazz number, but had found an appropriate groove elusive. Bicknell posited the idea of removing a beat and rethinking it as a bossa nova.

“The only song of theirs I had any actual musical input on,” the manager told me. “Mark was quite inclusive with his music. He would often ask me for suggestions, to which I’d more normally go: ‘Ooh, that’s a bit smelly.’ Democracy in a group never, ever works, but that doesn’t mean you have to shit on people.”

For the greater part, the basic tracks recorded at AIR were done with the band playing together out on the studio floor. Outside of these sessions, Fletcher and Clark found time to learn how to windsurf, while Knopfler was hunkered down with Dorfsman on the nuts-and-bolts details. Knopfler has abiding memories of those band tracking sessions.

“To have a man in every corner, playing with people that are really on their game, it’s phenomenal,” he says. “Plenty else stands out to me now. I remember going in one morning and Daddy George being in the kitchen cooking breakfast, a whole bunch of people working with him. Stevie Wonder came on the radio singing I Just Called To Say I Love You, and everybody started singing along. It was a moment of sheer joy, pure happiness.”

In early spring 1985, operations moved to New York City, and the familiar environs of The Power Station studio in midtown Manhattan where Dire Straits had made Love Over Gold and Making Movies. There, Knopfler set about adding horn parts to several of the songs, by jazz-playing brothers Michael and Randy Brecker and the Average White Band’s Malcolm Duncan.

Jack Sonni, a New York session player, was brought in to put a guitar synth on The Man’s Too Strong. When Illsley broke his wrist while jogging in Central Park (“A slippery path and the most stupid thing you could possibly do. I wasn’t even a runner, just in need of some air,” he bemoans), King Crimson’s Tony Levin and Neil Jason of the Saturday Night Live house band overdubbed bass parts. Notably in Jason’s case with his slap-bass contribution to the hitherto unremarkable track One World.

“Another happy accident,” says Illsley. “Both Neil and Tony brought different dimensions to the album, and which I wouldn’t have been able to do.”

“With a great collection of players, you’re in the business of realising things pretty quickly,” Knopfler adds. “Sometimes that might be something quite specific. There was one occasion, recording with Tom Walsh, a magnificent trumpet player, I sang the solo I wanted through the vocal mic. But that’s often not the case. You know, I wasn’t brought into the world to tell Randy or Michael Brecker what to play, and I didn’t. It’s a give-and-take thing.”

As Ed Bicknell told it, once they were at The Power Station, Knopfler decreed that Walk Of Life was better suited as a B-side. Upon hearing Dorfsman’s final mix of the track, Bicknell successfully lobbied to have it reinstated on the album. “And it went on to be a bigger-selling single worldwide than Money For Nothing.”

None of Knopfler, Illsley or Fletcher recalls hearing the Brothers In Arms album for the first time as a complete whole. Their lasting impression is of the looming tour, and a deadline clock ticking down towards it. Illsley does have a vague recollection of them gathering to compare the CD, vinyl and cassette versions of the album “at some studio or other”. He preferred the vinyl, “although the technology was still quite new at that particular time, and the compact disc would eventually sound better,” he says. “Then again, I might just be terribly old-fashioned.”

Five weeks ahead of the album, its laconic opening track, So Far Away, was released as the lead-off single in the UK.

The Brothers In Arms album cover was yet another happy accident. An American portrait photographer, Deborah Feingold, had flown out to Montserrat to do promotional pictures of the band for the record company. She just so happened to take a couple of frames of her assistant holding Knopfler’s shiny 1937 National resonator guitar up to a sunset, intended as nothing more than test shots.

Brothers In Arms met with scathing reviews from Britain’s music writers – the Straits had hardly ever been critical darlings in their homeland. NME berated Knopfler for his “mawkish selfpity… [and] thumpingly crass attempts at wit”. Melody Maker’s reviewer dismissed the album wholesale as “something very like the same old story”. But Brothers In Arms followed Love Over Gold to No.1 in the UK album chart. From there, says Illsley, “nobody could possibly have imagined it going on to sell the way that it did”.

Scheduled to run a full calendar year, the Brothers In Arms tour opened in Split, in what was then Yugoslavia, on April 25, 1985. But not without a hitch. The faintly ridiculous fact of Knopfler’s Synclavier sharing aspects of its internal workings with missile guidance systems caused it to be impounded at Yugoslav customs.

With Terry Williams back behind the drums, and Jack Sonni and a saxophonist, Chris White, on the tour, Dire Straits arrived in the UK on June 28. The same day, Money For Nothing was released as the album’s second single – and blast-off point. It was accompanied by a trailblazing computer-animated video by Irish director Steve Barron, brought in by Knopfler.

“To this day, I don’t really understand computer graphics,” says Illsley, “but I do remember that video being very expensive. The record company winced at the cost.”

In London, the band played 12 consecutive nights at Wembley Arena between July 4 and 16, where they were joined by guest artists such as Pete Townshend, Sting, and Knopfler’s teenage idol Hank Marvin.

A second show was slotted in on the evening of Saturday July 13, across the road at Wembley Stadium, where they took part in the Live Aid concert. The band took to the Live Aid stage at 6pm, in between U2 and Queen, and performed just a brace of songs: Money For Nothing, with Sting, and Sultans Of Swing. Even with such a truncated set, they were by now a powerfully formidable proposition.

"We literally walked off the stage, out of the stadium and across the car park to the Arena,” says Fletcher. “I think John was even carrying his bass – and to some quite funny looks from the car park attendants, I might add.”

Crossing the Atlantic, the tour wound on through North America that late summer and autumn, returning to Europe and the UK in the winter months, then proceeding in the New Year to New Zealand and Australia. They played a total of 248 shows in 118 cities. Along with it, Brothers In Arms maintained unceasing momentum: nine weeks at No.1 in the US. The UK’s best-selling album of 1985, beating Bruce Springsteen’s Born In The USA, Madonna’s Like A Virgin and Phil Collins’s No Jacket Required. Enough for even the habitually undemonstrative Knopfler to be somewhat taken in.

“Yeah, I loved it,” he says. “But when you’re in the eye of the storm you don’t really notice it. It was a lot to pile up in a life, you know. There was one occasion a youth in Manchester shouted out to me on the street: ‘You’re top, man.’ No, no, no. I didn’t feel as though I was top of anything. I never did.”

They played the final show of the tour at Sydney Entertainment Centre in Australia on April 26, 1986. Afterwards they parted with handshakes and hugs and little fanfare. The band were destined not to come together again for more than four years. Both Illsley and Fletcher allowed themselves the extravagance of a new car, a Bentley and a Porsche respectively. Knopfler retired to muse on things. In September 1988 he announced the dissolution of Dire Straits and formed a country-rock outfit the Notting Hillbillies, with Fletcher on piano and Ed Bicknell on drums.

All told, the sheer success of Brothers In Arms seemed to catch Knopfler as much as anybody off guard. To what degree and effect we won’t be finding out today. Fifteen minutes prior to the end of our appointed time, his assistant enters the room, one hand making a chopping motion across his throat.

“I think we’re being hooked,” Knopfler says, as if surprised. At any rate, by accident or design, he’s spared having to revisit the Straits’ ill-starred last-gasping.

In the event, he did summon the band back together. In November 1990 they convened at George Martin’s AIR London studio on Oxford Street: Knopfler, Illsley, Fletcher, Clark, and with Toto drummer Jeff Porcaro in place of the departed Williams. There they recorded one more, final, album, On Every Street. It was pleasant, but undemanding, and no more than a wisp of its illustrious predecessor. After it, an even longer tour, described to me by Ed Bicknell as “an utter, utter misery. Whatever the zeitgeist was that we’d been part of, it had passed”.

“It was exhausting for everybody, mentally and physically, no doubt about it,” says Illsley. “The decision to end the band once and for all was made at the end of the tour. Mark was getting a lot of attention, and he didn’t want to be playing in these huge places any longer. He wanted to do something different, and I completely understood. I was very happy.”

There has been no third act for Dire Straits ever since. But Brothers In Arms has never gone away. It’s now the UK’s all-time eighth-best-selling album, level-pegged with Michael Jackson’s Thriller. In the intervening years, the band’s stock has risen. Dire Straits were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2018, but Knopfler skipped the ceremony.

Generally he has stayed out of the limelight, while continuing to make music. To date he’s made 11 dependably solid solo albums, plus collaborations with Chet Atkins and Emmylou Harris. He appears thoroughly content with his lot, happy to be pleasing himself. Charmingly, he says he goes to the studio to write these days, because the ringing of the doorbell is too much of a distraction to him at home. “All those Amazon deliveries,” he huffs gently.

Fletcher has remained at his side, recording and touring with his band. Illsley, too, has made a bunch of solo records, and plays the odd festival. He has also forged separate career paths as an exhibited painter and the proprietor of the East End Arms, a gastro pub near his Hampshire home. They do assemble intermittently to reminisce with each other, says Fletcher, “and joke about some of the things that happened. Most of them never to be repeated. There were tough times as well, but we don’t dwell on those.”

“Mark and I are good mates to this day,” says Illsley. “I’m very grateful for that. But to do it all over again? My god, I think it’d be better to kill us. There’s a time and a place.”

Before Knopfler took his leave, there was just time enough to ask him when he last sat down and listened to Brothers In Arms in its entirety. He pushed his glasses up his nose, the expression on his face changing at a stroke from its default pensively crumpled state to one of mild bafflement. “Never, never, never,” he replied with a chuckle. “I don’t ever go home and play my own records. Life’s tragic enough without that adding to it.”

The expanded reissue of Brothers In Arms is out now via UMC/EMI.

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.