“We showed up and Dire Straits were opening for us. The press slaughtered us, accusing us of being dinosaurs”: The epic story of Styx’s Pieces Of Eight, the pomp rock masterpiece that began to tear them apart

Styx’s 1978 album Pieces Of Eight was a watershed moment for the pomp rock stars – for good and for bad

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

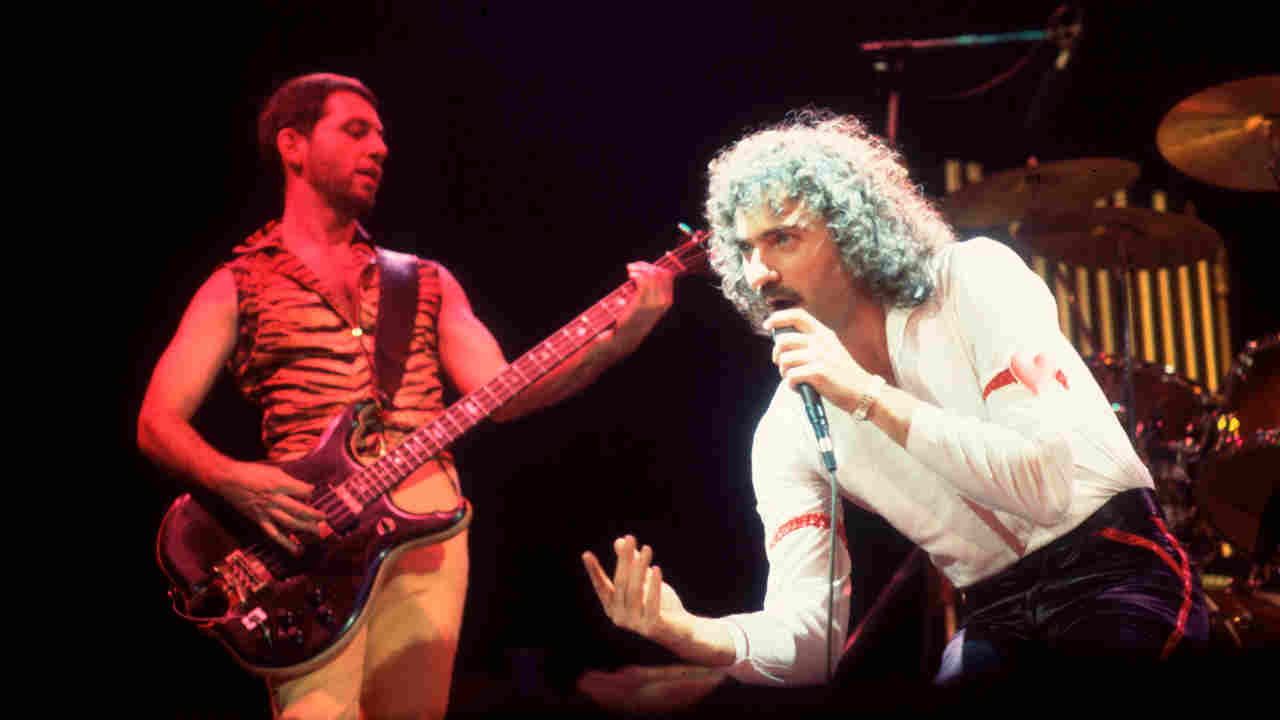

Styx were one of the biggest American rock bands of the 70s – and 1978’s Pieces Of Eight album was their high water mark. In 2013, estranged singer Dennis DeYoung and guitarists James ‘JY’ Young and Tommy Shaw sat down with Classic Rock Presents AOR magazine to look back on the making of a pomp rock masterpiece.

As far as most traditionalists are concerned, Styx’s Pieces Of Eight represents all that’s most remarkable about the band, their music and their ideology. Their eight album, released in September 1978, it took all that was great about their previous records and combined them into one glorious bundle of fun, successfully fusing – perhaps for the first time – progressive rock, pomp rock and hard rock, elements expressed as a force of nature rather than just haphazard experimentation. It is a blueprint – a road map, if you will – of what can happen when accomplishment and success grab the wheel and make a sharp left turn on to an unchartered road. A destination that some of the band are still trying to come to terms with to this very day.

Within a few years, irreversible divisions had begun to split up the group, leading to their initial demise in 1984. There have been partial reunions over the years, though today singer Dennis DeYoung remains estranged from his former bandmates. But despite their differences, DeYoung and guitarists Tommy Shaw and James ‘JY’ Young – who are still both members of Styx – agree Pieces Of Eight was the last truly formidable Styx album, one where everybody played a positive part.

“You see, the thing about Styx was that we were a very good-humoured band,” says Dennis DeYoung, sounding larger than life and brandishing a supersonic fanfaronade of enthusiasm. “And another misconception is that we went at each other hammer and tongs. I don’t even think there was any underlying anger or any passive-aggressive feelings. I really don’t believe that. If that were the case, then those with the biggest fists would be the only survivors. The original premise was to get together and create something collectively, so when I hear nonsensical accusations about fighting each other it doesn’t make sense. Sure, there were creative differences, but how can there not be? That fact that rock bands stay together for as long as they do is a miracle.”

James ‘JY’ Young is also philosophical about those years. “It’s said that great works of art come from creative tension, conflict or troubled times. The fact that Dennis, Tommy and I were headed in different directions worked well, leading to songs of an incredibly high standard. In hindsight, the spirit of that thing worked, and there was a magic about that collective of people at that point in our lives.”

You can trace the formation of Styx back to the early 1960s, when brothers Chuck and John Panozzo, two mad-keen music fans from the Chicago suburbs, started a garage band called The Tradewinds, which Chuck on bass and John (who passed away in 2016) on drums.

With the addition of keyboardist Dennis DeYoung, they subsequently switched moniker to the more streamlined TW4, and later that decade added guitarists John Curulewski and James ‘JY’ Young. Building a reputation as a hot live band, they signed to local Chicago label, Wooden Nickel Records, partly owned by renowned media mogul and concert promoter Jerry Weintraub. The label insisted on a new name and, following exhaustive discussion, they refashioned themselves as Styx, chosen only because none of them hated it.

They recorded four albums for Wooden Nickel, all broadly progressive rock with elements of hard rock and a few sappy ballads thrown in for good measure. Indeed, as a precursor to later recordings, 1973’s The Serpent Is Rising was thought to be vaguely conceptual, hinting at a style they would bring fully into focus further down the line. Incredibly, however, two years after its original release in 1973, the album Styx II featured a track titled Lady, which emerged as a regional and then national hit single, reaching the dizzy heights of No.6 on the Billboard chart.

It was this success after years of struggle that finally prompted the band to look for a more influential record label. Wooden Nickel was awash with problems; not least of all restrictive studio budgets and, perhaps most damning, a management clause in the contract. Despite an attempt by RCA (Wooden Nickel’s distribution company) to then secure the band’s signature, it was growing independent label A&M that eventually signed them. It was also A&M who introduced them to their new manager, Derek Sutton, an Englishman who had previously worked with a number of quality acts, including Robin Trower.

With a new label, money and freedom they set about recording Equinox, an album that would herald a more focussed and perhaps more commercial approach. Issued in 1975, and engineered by long-term studio cohort Barry Mraz, the album was heralded as a fine statement of intent. It was also housed in one of the most striking album sleeves of the period: a flaming block of ice set in a surreal beach scene underneath an angry green sky.

This unique image somehow identified a few key elements of the emerging Styx sound, suggesting JY’s aspirations as a hard rocker (which later became his brand identity), ably demonstrated by the taut guitar riff of Midnight Ride, along with Dennis DeYoung’s adventurous prog rock ambitions, best exemplified by Suite Madame Blue and Lonely Child, a deceptive combination of ballad and brawn. To cap it all, the band scored another Top 30 US hit with Lorelei. But while they had everything to play for and nothing to lose, they suffered a setback when guitarist John Curulewski (who passed away from a brain aneurysm in 1988) left the band almost immediately after the recording sessions, on the eve of an impending tour.

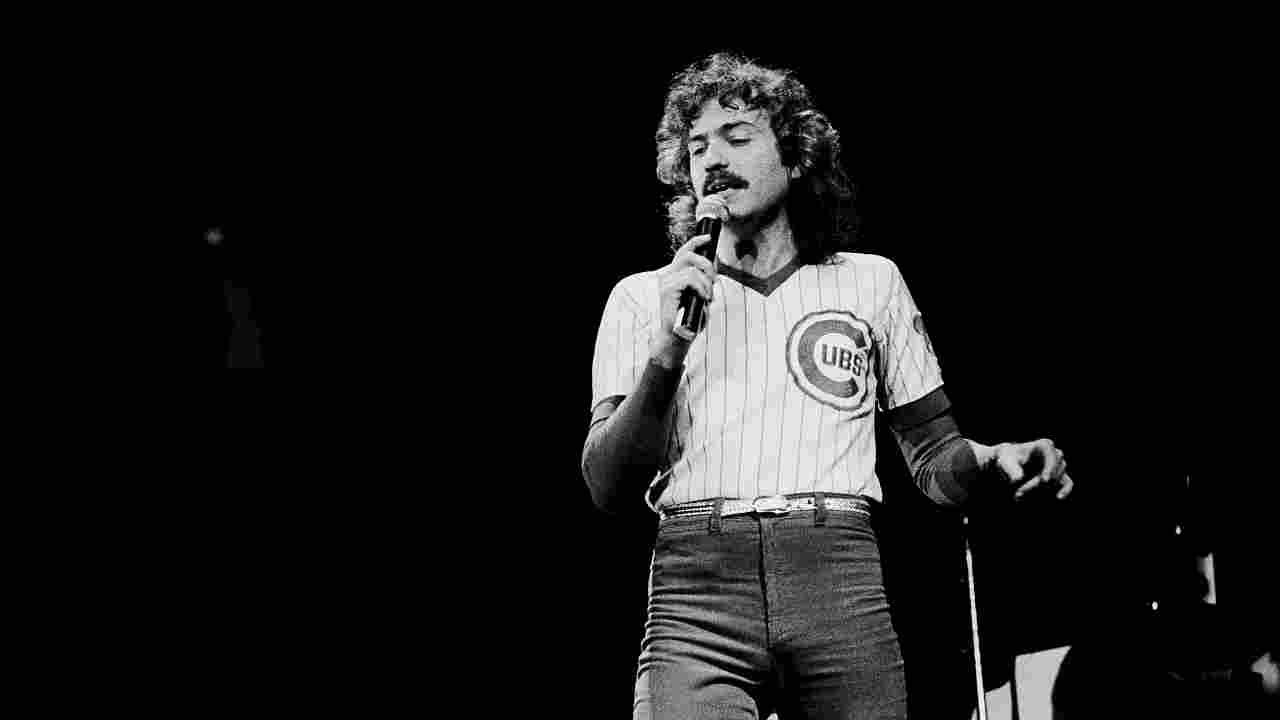

The hunt was on to find a suitable replacement; not an easy job considering the demanding skill set required, and the fact that a tour was looming. Fortunately, Styx soon found their man in Tommy Shaw, a seasoned but previously unknown guitarist/songwriter who had played in a local Chicago band with the unlikely handle of MSFunk. Although they recognised Tommy as a great guitarist/vocalist and a dynamic performer, they weren’t aware of his songwriting ability. But once this became apparent, the rest of the band felt like they had won the lottery.

Making his debut on 1976’s wonderfully crafted Crystal Ball album, Tommy’s impact was felt immediately, having penned the title track and contributed to several other key moments. The album remains one of Styx’s most impressive statements, picking up the pomp rock baton from Equinox and crafting an even more concise and flamboyant opus.

At the heart of the process was their ability to fuse traditional British progressive rock with all-singing, all-dancing American razzle-dazzle. Again, JY was let loose, with the taut, straight-to-the-point shock rock of Nu Shooz, while Clair de Lune/Ballerina showcased Dennis DeYoung’s burgeoning theatricality and was, for many, the high water mark of the album. Tommy Shaw, meanwhile, scored a big coup: not only did he co-write and sing lead vocal on Mademoiselle, the album’s lead single, but it also became the album’s only hit, cementing his position in Styx.

Behind the scenes, however, Dennis DeYoung was – even at this early juncture – feeling the pressures of being part of an in-demand rock band. He began to feel that his life – and to a degree his destiny – was being ruled by Styx, and not the other way around. This wave of despondency would last for some time, but would also go on to fuel some of his, and the band’s, greatest work, their next two albums, starting with 1977’s The Grand Illusion.

“Effectively, I think the band really started to coalesce with the Equinox album,” confides Dennis. “Then, when Tommy came in, it really started to get interesting. The Grand Illusion was just another step that found favour in a much bigger way.”

Dennis sings us some lyrics from the title track: “‘Someday soon we’ll stop to ponder what on Earth’s this spell we’re under/We made the grade and still we wonder who the hell we are.’ That is the theme that goes throughout my writing.”

And it wasn’t just Dennis who was feeling a sense of unease with newfound fame and wealth.

Tommy Shaw: “Much of The Grand Illusion album was to do with the disillusionment of finding out that the things we had all dreamed about weren’t quite what they were cut out to be.”

Recorded once again in Chicago at Paragon Studios, with Barry Mraz engineering, The Grand Illusion was a masterpiece of pomposity. It was, to that point, the culmination of Styx’s entire career, a record shoe-horned full of songs that have stood the test of time, propelling the band into the superstar league. Indeed, to this day fans feverishly debate whether The Grand Illusion or Pieces Of Eight is the group’s superior release, a topic dividing them into roughly equal constituencies. Of course, such petty squabbling misses the point that we have two great works to enjoy, both of which being the finest examples of what pomp rock has allowed us sinners to enjoy.

Themed certainly, but not truly a concept album, The Grand Illusion was informed by Dennis’s aforementioned concerns about life in the fast lane and all the pressure that was bearing down on him. He was not alone either. Other members of the band were also noticing unwelcome demands with fame and fortune. Classic songs such as Come Sail Away, Castle Walls and the title track revealed the group absorbed in self-doubt over what they were experiencing. Even mad axeman JY chipped in with a fine slice of acerbic observation in the riff-hungry Miss America, a song that shakes a firm fist at the shallowness of consumerism.

Says Tommy: “You write what is on your mind. You travel together and often talk about the same topics like what’s going on in the world and in your personal life. These subjects are always present so it’s kind of like a functioning organism. It’s natural to have similar influences coalescing and that is the overriding principle; shared experiences.”

The problem with making a record as strong as The Grand Illusion is that you are immediately forced into a position of having to serve up something slightly better next time around. That’s a tall order and one that many acts have failed to achieve. For Styx, working under a cloud of constant duress, it was no different. With their shared experiences and similar thoughts in mind, they commenced writing new material only to later find that the songs were thematically linked.

Over the years it has wrongly been stated that Pieces Of Eight is an actual full-bodied concept album but that is not true. All members of the band deny the accusation but they do agree that the essence is uniform, isolation, disappointment, frustration, mistrust and duplicity being at the forefront of their emotions.

“We never really made a concept album ever,” explains Dennis. “If I listen to Dark Side Of The Moon is that a concept album? You could say we had thematic albums but that’s different. You explain the theme to somebody and they basically give you their take on it or not. There was no cane in Styx which said don’t do this… or else. Take it as you will; it’s just a discussion. The premise was always based around: ‘What do you think of this idea?’”

“There was never an intentional theme,” JY is quick to confirm. “Five young men had finally gained success. We achieved our goal and finally the money and all its trappings were rolling in for us. By the age of 30 we were doing well for ourselves. You always dream about how your life will change when you become successful but in reality going from having very little to having lots is a transition that affects you personally, professionally and emotionally in ways that you didn’t expect – and in a way those sentiments are reflected in the title of the record.”

Tommy: “We were still in the golden moment of time where we were in a band together, travelling together, playing together… y’know, paying our dues. We went from struggling to keep our heads above water, to reaching the point where some of the things that start to whittle away at bands appeared. At this point though, none of that stuff had taken seed. Then we had The Grand Illusion, which was a huge success, and we were just coming off the back of that, so we still had that little golden moment, going into the creation of the follow-up album.

“The success of The Grand Illusion was still reverberating and, in fact, increasing as we started recording Pieces Of Eight. Naturally you look at your previous work and think: ‘Why did that work so well?’ And then you try to go down that road again. You can’t help but do that, but of course it’s better to start afresh. To be suddenly recognised and respected was fantastic, so we were all feeling very creative at that point.

“We had improved at the art of making albums,” he continues, “so the record appeared like it was a concept, as the songs flowed together and the arrangements made sense. The flow from one song to the next and stuff like that can easily be mistaken as a concept. It was really just about creating a record that flowed and hung together making sense.”

Dennis DeYoung offers further insight: “The experience that I went through is why the album was called Pieces Of Eight. You see, success brought so many different situations into the picture, like wealth, stature and power. People who I thought were my friends, and even my relatives, became jealous of me in terms of my success and fame, and that was startling to experience. Joe Walsh said it brilliantly in his song Life’s Been Good: ‘It’s tough to handle this fortune and fame/Everybody’s so different, I haven’t changed.’”

Pieces Of Eight was an immediate success, achieving triple-platinum sales and placing the band at the centre of a media scrum that few hard rock bands – especially progressive hard rock bands – have ever experienced. While the public lapped up the records and bought concert tickets in their hundreds of thousands, highbrow critics berated the band, pouring scorn on their achievements and penning reviews that completely missed the point. Rolling Stone magazine in particular had been particularly contemptuous, and so manager Derek Sutton cut off all communication with the rock press, a move the band later came to regret.

“Derek kept us away from the press, which was the wrong decision,” observes Dennis. “Instead of engaging them, we were pilloried by them and that was difficult to explain, except that three million people wanted to buy our records and see us in sold out arenas. Led Zeppelin stuck to their blues-based thing for the most part for a long time and didn’t release singles, saying: ‘The rest of the world be damned.’ That works well if you’re Pink Floyd or Zeppelin, or a band of mystery. But for a band like Styx whose first hit was Lady, that doesn’t work. Instead of antagonising the press with our refusal to engage, we should have embraced them.”

Pieces Of Eight refined the group’s sound and – although it was not apparent at the time – would be their last record to coalesce like a classic Styx album. Let’s not beat around the bush here, if you are looking for that chocolate-box selection of great Styx sounds, then this is their final great pomp rock moment, before the likes of Babe, Boat On The River and Mr Roboto radically shif the goal posts.

Recorded once again in Chicago, with the illustrious Barry Mraz promoted to the grand title of Production Assistant, the record opens with the rollicking Great White Hope, another classic JY rocker that sets the thematic tone for the rest of the album.

I’m OK, penned by DeYoung, is a stark confessional, neatly summarising his on-and-off bouts of self-doubt and disillusion during the preceding years.

“Actually it’s a co-write with James, but it was predominantly my song,” Dennis says. “So many times I write songs to remind myself what I should be thinking when I’m certainly not. I went through a very difficult period in 1976, 1977 and parts of 1978 where I suffered from depression and anxiety. This song was really me trying to remind myself that I was fine. It wasn’t meant to be some sort of pop psychology ‘oh, good for me’ type thing. It was actually coming from a much darker place. In retrospect I was probably trying to act like my own cheerleader.

“When I became very successful and very rich, and I realised it wasn’t what I thought it was going to be, that’s when I became reacquainted with reality. I’m OK was also part of the process which helped to cure it. Interestingly, it’s one of the Styx songs that I find people talk to me about the most. It seems to be a song that’s helped people to get through life and made them feel hopeful, but what I was trying to do was make myself feel hopeful.”

Sing For The Day, penned by Tommy, is a tribute to the audience and their belief in, and support of, Styx’s music. The song name-checks a girl called Hannah, but is not about his daughter, as fans have commonly thought…

“My daughter’s name is Hannah,” says Tommy. “She’s always being asked: ‘Did your father write that song about you?’ But she’s 26 and that song was written in 1978 – you do the math! The original name of the girl in the song was Anna, until Dennis’ keyboard-tech’s daughter came to a show. Her name was Hannah and I figured that that sounded better than Anna, so I changed it.

“I used to go on stage and study the people in the audience, y’know, constantly having these little moments of eye contact. Something happens when that occurs, like a little electrical spark. Actually, it’s one of the addictive things about playing live. Anyway, I was starting to notice that the audience wasn’t, on average, getting older – there were always young fans coming to the shows and Hannah was, in my mind, the perennial young fan.”

The Dennis DeYoung-penned Lords Of The Ring has nothing whatsoever to do with JRR Tolkien but is, once again, an acerbic observation on the cult of stardom, a nod to the fact that self-aggrandising rock musicians are like modern-day pied pipers. It was also a personal allegory, comparing his quest for fame and fortune and then realising that he was still dealing with the same issues.

“The song was a metaphor for those who’ve become lords of the ring,” explains Dennis. “‘All hail to the lords of the ring, to the magic and mystery they bring.’ It was really about the silliness and the façade of being a rock star, of the realisation that success, in all of its manifestations, was not really going to give me fulfilment.”

“Lords Of The Ring might be one of the best-ever examples of pomp rock,” opines JY. “That song is definitely a guilty pleasure. Originally, Dennis was going to sing it and I was slated to sing I’m OK. But that song [I’m OK] was such a personal statement about himself that he ended up singing it and putting me on Lords Of The Ring.”

Side two features a brace of quintessential Styx classics, opening with Blue Collar Man, a Tommy Shaw hard rock nugget featuring Dennis DeYoung on very angry Hammond organ, and lyrics that pay homage to the working man.

“I originally wrote that song on an acoustic guitar,” reveals Tommy. “It was quite a dark acoustic song. Once again, we electrified it and brought the growly organ in, which was a last-minute thing. We had to fight Barry Mraz on that, because as an engineer he was such a purist, and we kept turning it up to get more distortion. Dennis played that part on a really nice B3 organ – it’s still in the warehouse.”

Queen Of Spades, a thinly veiled comment about the lure of gambling, navigates a quiet start before erupting into pomp rock glory, finally returning to the mysterious melody that it started with in the first instance.

“That was a co-write with JY,” notes Dennis. “My involvement amounted to singing the melody while JY was responsible for everything else, all the chords and the lyrics. Those are his lyrics.”

Renegade, written by Tommy Shaw, is arguably the icing on the cake, with spine-tingling lyrics, a spooky vibe and one of the best guitar riffs of all time. Of course it all pivots on a brilliantly pompous tempo, while the middle eight features some of the band’s finest harmonies. Listen out, too, for a killer JY lead guitar solo and Tommy’s truly monster vocal performance. No wonder this song reached the US Top 20 with ease.

Tommy: “It started out as a dirge, three-part harmonies, and very slow, so we kicked up the energy and suddenly everything changed and all the goodness of the song came through. That’s the funny thing about working with the band back then – it was just about making the song the best we could.

“I don’t know where those lyrics came from,” he adds. “They just came out of nowhere. Those are always the best songs; they just channel themselves through you. I guess there has to be some kind of release, when you’re not running away anymore and you’re faced with resigning yourself to the fact that the end is inevitable, yet thinking about his mother there is regret. That part was me.”

Dennis: “Tommy brought in Renegade, and it was very different song at that time. At rehearsals I said to Tommy: ‘I think there’s a rock song lurking in here, how would it sound if you were singing and playing it by yourself?’ The rest of us stood around and joined in and that’s how Renegade became a rock song. It was not a rock song when written – it was never intended to be.”

“Here’s another interesting story,” adds Dennis. “Blue Collar Man comes out and does well, and then the label decides to release Sing For The Day, and on the b-side was Renegade. We were on tour, and whenever we played Renegade, our drummer John would stop in the middle of the song and get the entire audience to scream ‘Toga! Toga!’ – like in the movie Animal House. It was so dynamic live that when the Sing For The Day single came out, the radio programmers flipped it to listen to Renegade. Not the record company and not the geniuses in the band. That’s how Renegade became the second hit.

“I believe that if Renegade had actually been released as a single it would have been a Top Five track, maybe a No.1,” Dennis adds. “Well it would have been in the Top Five for sure. As it was, it never got higher than, I think, No.16. It broke slowly.”

The last song on the album is the title track, which is another Dennis DeYoung confessional.

“It’s one of my favourite Dennis DeYoung songs of all time,” confesses Tommy. “I think that if Renegade hadn’t done so well as a single, then it would have emerged as more of a classic song. It had all the great Styx elements to it: a great lyric, beautiful melody line, big three-part harmony chorus and a melodic guitar solo. A timeless song, and we still play it.”

The record ends with glorious and magisterial pomp rock grandeur. But wait, there is a final sign off: an instrumental titled Aku-Aku, composed by Shaw, providing a neat and serene conclusion to the album. Named after a somewhat controversial book, titled Aku-Aku: The Secret Of Easter Island written by Norwegian archaeological explorer Thor Heyerdahl in 1958, the piece provides a contemplative, dare we say, progressive conclusion.

“Back then, we loved the production values achieved by Alan Parsons,” admits Tommy. “Real headphone-friendly stuff, like an aural trip through the stereo spectrum. Aku-Aku has that dreamy quality to it, y’kno… fading off into the sunset.

“A few years ago we toured playing the entire Grand Illusion album, followed by Pieces Of Eight. The final song is, of course, Aku-Aku. Normally we end our shows with one of the big anthems like Renegade or Come Sail Away, so we were nervous about finishing with a quiet song, because it’s not what our audience expects. But it turned out great. We had a film of Easter Island projecting behind us, and then the camera pulls up and out into space, and that in many respects is what Aku-Aku represents.”

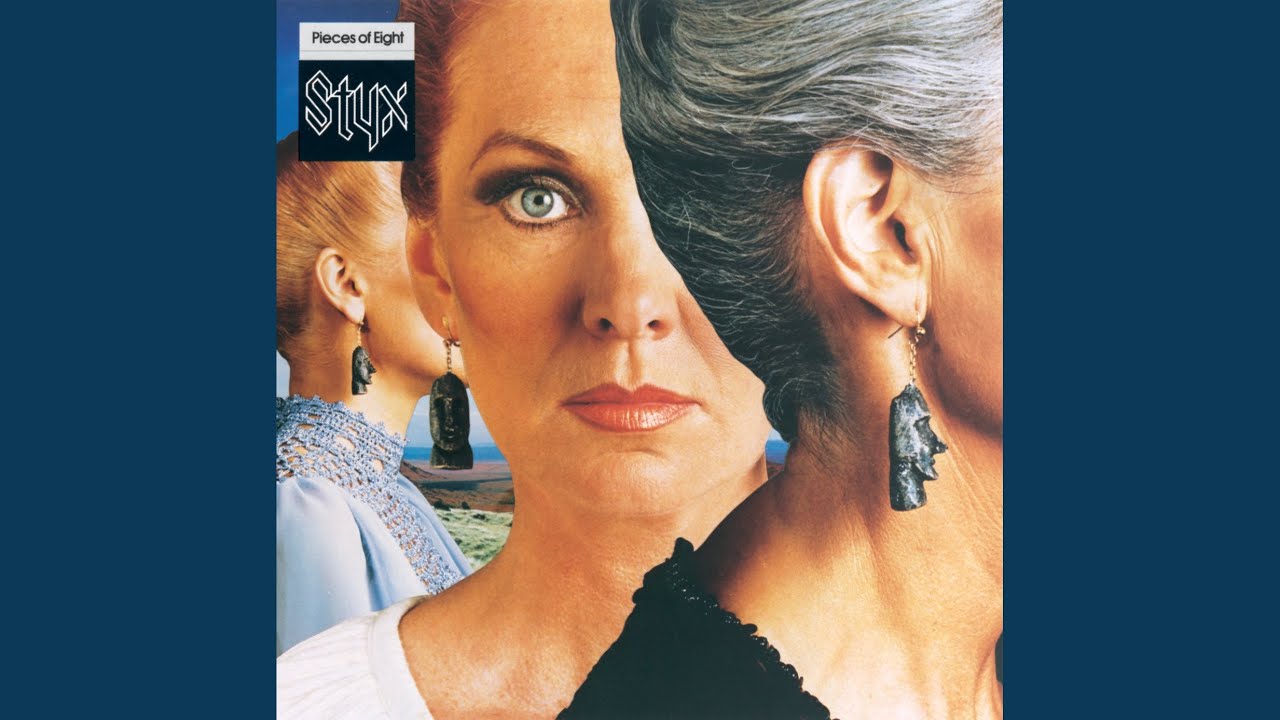

The Pieces Of Eight album artwork, a fantasy image created by Hipgnosis, depicts older, finely chiselled female models, set against the Easter Island landscape, wearing miniature stone monuments as earrings. The entire band now agree that, despite early reservations, it’s an iconic image. Intriguingly, such was Styx’s huge popularity, the album was originally issued without the band name or album title, a feat only matched by Led Zeppelin for sheer audacity.

“We went to Hipgnosis and got some phoney baloney artwork,” laughs Dennis. “They sat us down and gave us a two-page description of what it was about after listening to the music. When I first looked at it I said: ‘What are they doing, putting those old women on the sleeve?’ The funny thing is those broads look pretty good to me now. There’s a couple of our sleeves that I don’t like, but I think in general they were good. But at the time I hated the Pieces Of Eight cover; now, though, I really like it a lot. As the years have gone on, it has become iconic. I also really still like The Grand Illusion’s sleeve artwork, fooling round with the René Magritte stuff. Those two album covers, I strongly believe, are our best.”

What of the notion that Pieces Of Eight was the last great Styx album?

“I wouldn’t disagree with that,” opines Dennis, with a surprisingly agreeable tone. “I understand that position. We developed a style, had success with it, and when you do that, the audience fully commits to what you told them that they should like. Not surprisingly they might be reluctant to accept any changes. I thought The Beatles had gone mad when they released Rubber Soul, and then I realised that it wasn’t madness, so I had to figure out whether I wanted to go with them or not. We made the same sort of change. Cornerstone was a change, no doubt about it. It wasn’t Rubber Soul [chuckles] – and I understand why it was met with doubts.

“Frankly, I blame the English – we went and toured there in 1978. We’d just had success in the USA and the press in the UK eviscerated us, because it was Johnny Rotten time. We showed up and Dire Straits were opening for us. The press slaughtered us, accusing us of being dinosaurs. I came back to the States convinced that they were right about prog rock being dead. In many respects Pieces Of Eight was like the coda from when we started in 1972.”

“I fully respect that opinion,” JY agrees. “A lot of it was due to the fact that Barry Mraz [who sadly died in 1989] stopped being our engineer. Dennis was unhappy working with him and was, ultimately, looking for a different approach. In hindsight, Barry was a sonic genius – he made us sound like Styx. We moved on to work with Gary Loizzo who was much more into vocals and less of the British rock sound that we had loved so much.”

“It was the end of our innocence,” laments Tommy. “We were all drinking from the same cup, and sharing the same musical thoughts. It was also the first time that things shifted a little bit. Up until then I had been the new guy, but Blue Collar Man and Renegade had emerged as big radio rock tracks and I was getting a lot of attention. It was an adjustment for everybody, not least of all for me. Money started coming in, and that emphasised the awareness that songwriting produced different levels of income, and that starts to whittle away at a band. These were golden days, when everybody was pulling just for the sake of the music. After that, letting other people work on your songs started to evaporate. I used to love collaborating. Y’know, injecting a middle eight or a guitar solo – little flavour changes to get you away from the main thrust, so when you get back to the song it sounds interesting. If I were a fan I’d notice it. You’ve got to look at it as an exploration – you start seeing the culture change, and things become different.”

Pieces Of Eight sold three million copies but it also signalled the end of an era. Sure, the band would go on to have bigger hits and achieve even more album sales. But the fact remains that this was a record that would never be topped stylistically. Indeed, the band’s next move would be to record Dennis DeYoung’s sentimental Babe, a song that was never even meant to be a Styx track, but propelled them into a new stratosphere of success.

“I think that the fact that my songs were successful had a huge influence,” admits Tommy. “Up to that point it had been more ‘the Dennis show’, with JY covering the rock end of it. Then suddenly this little shit from Alabama steps in there and all this is happening. I was still young and naïve, plus it was kind embarrassing for me to be getting all that attention. I liked it but I could see it was making things uncomfortable.”

With the benefit of 35 years of hindsight, how do the group feel about Pieces Of Eight?

“It sounds like all the songs pretty much came from the same band I think,” offers JY. “There’s a majesty and, for lack of a better word, a pompousness to it. If you will.”

“When I listen to Pieces Of Eight now, I think that it’s really a lovely piece of work for that particular time, but overall I was very disappointed with my contributions as a writer,” says Dennis, with total honesty. “I had felt that, after eight albums fooling around with what I would call the Americanisation of English progressive rock – with a sugar-coating of hard rock and pop – we were treading the same ground. We were never an easily definable band. I hear progressive rock people proclaiming that Styx was not a ‘prog rock band’ and I agree with them. Who said we had to be? We were making shit up as we went along – we weren’t Gentle Giant. Most of the progressive rock [influence] in the band came from me, because I was the guy with the classical music background – I was a music teacher and, y’know, it’s a style that lends itself to keyboard players. But after eight albums I felt musically bankrupt as composer. When you try to take those minor chords around the block one more time and you’ve put ’em through the fuckin’ ringer, the lustre wears thin. I never liked my contribution. I think that was Tommy Shaw’s finest work in Styx.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents AOR issue 11, September 2013

Derek’s lifelong love of rock and metal goes back to the ’70s when he became a UK underground legend for sharing tapes of the most obscure American bands. After many years championing acts as a writer for Kerrang!, Derek moved to New York and worked in A&R at Atco Records, signing a number of great acts including the multi-platinum Pantera and Dream Theater. He moved back to the UK and in 2006 started Rock Candy Records, which specialises in reissues of rock and metal albums from the 1970s and 1980s.