Fields Of Dreams: how the original festivals shaped the future of rock music

In the late 60s and early 70s, rock music was synonymous with Festivals. Some of the events still exist today, but back in the day they could turn innocent hopefuls into household names

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Almost by the time the flames had gone out on his mangled Stratocaster and the wreckage had stopped smouldering, Jimi Hendrix’s performance at the Monterey festival in California in June 1967 had transformed his profile in the US from little more than an underground figure with a still-to-be proved reputation filtering over from Britain, into a full-blown supernova superstar.

With that one ‘homecoming’ performance in which he pulled out all the stops (and a can of lighter fuel with which he anointed his sacrificial Strat), Hendrix had arrived. So too had the popular music festival – and its ability to give artists unprecedented exposure for one show, and in some cases, give them their big break.

In the late 60s, music had not yet become the all-pervasive global entertainment that it is today, and had yet to be swallowed up by the dollar-driven industry behemoth. Apart from the music in the charts, the way music fans heard about bands/artists (and listened to music) was very different. Even The BBC's Radio One was still in the flush of youth. Only John Peel’s show, Mike Raven’s Saturday evening R&B show and a handful of other radio shows provided an outlet for anything that wasn’t strictly mass appeal.

There were three or four weekly music papers; monthly music-dedicated magazines were still years away, other magazines’ coverage of even mainstream music was perfunctory, and daily papers’ coverage would be either high-brow (the broadsheets) or hung on a scandal or a genuine hard-news angle. Unless you lived in London (and often even if you did), it wasn’t unusual to have to order an album from your local record shop (usually the only one in town) and then wait weeks for it to arrive. Compared to today, non- commercial rock was an underground phenomenon.

The majority of these relatively unknown, ‘underground’ bands in the UK who spent most of their lives on the road were blues/blues rock/R&B bands. Many of them routinely gigged for years before they even got a sniff of a record deal or saw inside a studio, traversing the country in van and regularly playing 200, 300 or more gigs a year, often to audiences of a few dozen.

No wonder, then, that the music festivals that sprang up in the 60s played such an important role in giving up-and-coming – or even completely new – bands the kind of exposure and resulting word-of-mouth seal of approval from playing one short set that they would otherwise have to gig around the country for months to get.

To the extent that a single festival appearance could tip the balance and lift a band out of cult following half-light into the glare of commercial and critical success. Of course, it helped that back then virtual unknowns were regularly invited on to festival bills (and without the big-bucks buy-on).

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In Britain, the National Jazz & Blues Festival – which ran throughout the 60s at a number of sites, then from 1970 became better known as the Reading Festival when it took up residence in the town – was particularly important to British blues rock bands.

Over the years it hosted names artists like The Yardbirds, The Who, Cream, Spencer Davis Group, Traffic, Small Faces, Jethro Tull, The Nice, Family, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, Jeff Beck, Pink Floyd, Fairport Convention, Arthur Brown, Tyrannosaurus Rex and Joe Cocker, along with a whole host of smaller bands, many of which got their big breaks at these festivals. Audience acclaim often lead to a hugely important residency at the prestigious Marquee club in London; some even got a record deal as a direct result of their appearance.

One band that certainly felt the ‘festival effect’ was Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac (as they were originally called). Having got a full line-up together only a month before, the band’s first ever gig was in front of 30,000 people at the National Jazz & Blues Festival in 1967, held in Windsor.

From that brief, 20-minute set, word of mouth would certainly have boosted sales of their debut album, released less than six months later. It reached No.4 in the UK – a remarkable achievement for a blues album, and a debut at that. Fleetwood Mac quickly established themselves as arguably the best British blues band of the era.

Also playing at the 1967 Windsor Festival (the final day headlined by Cream) – and making their debut with a new line-up were Chicken Shack led by guitarist Stan Webb. From an acclaimed and profile-raising set, they were able to gig intensively and extensively for months afterwards, and became one of the bigger names on the UK blues circuit. They were soon signed to pioneering and hugely important British blues label Blue Horizon (also the home of Fleetwood Mac), and the following July released their first album (it reached No.12).

Ten Years After, already in the ascendancy due mainly to guitarist Alvin Lee’s lightning-fast licks, perhaps didn’t establish themselves at that landmark festival in Windsor in 1967, but it was there that they consolidated their reputation as one of Britain’s premier blues rock bands. Cocked and loaded following a residency at the Marquee, they “fairly stole the show”, according to music weekly Record Mirror.

Which would have been no mean feat for a band still without a record deal, and on a day that also had Pink Floyd on the bill. Within months Ten Years After released their debut album. Two years later, following a string of US festival shows, the band floored half a million people with an incendiary display, crowned by a spun-out Goin’ Home, that was one of the highlights of the legendary Woodstock festival in 1969. With their Woodstock performance, Ten Years After effectively cracked America .

Woodstock was also the launch pad for the then virtually unknown Santana, whose intoxicating show-stopping performance went into orbit and certainly helped propel their Latin-rock fusion debut album to the dizzy heights of No.4 in the US five months later.

By the end of the 60s, in just three or four years – and, poignantly, post- Woodstock – the nature of festivals had changed dramatically. The 1969 Bath festival, with Led Zeppelin on the bill along with the likes of Deep Blues Band, Roy Harper, Chicken Shack, John Mayall and Fleetwood Mac (a very bluesy, very British affair), drew 12,000 people.

The 1970 Bath festival’s big-name, American- loaded bill included The Byrds, Johnny Winter, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa, Country Joe, Santana, Canned Heat, Pink Floyd and The Moody Blues. As the sun set behind the stage on the Sunday, show-stealers Led Zeppelin played to a crowd of 150,000. No one on this bill was looking for a big break – or even a record deal.

Similarly, where the 1969 Isle Of Wight Festival bill was still packed with British blues-based bands for whom it could be their springboard to greater heights (Edgar Broughton Band, Free, Aynsley Dunbar, Blodwyn Pig, Mighty Baby) alongside stars The Who and Bob Dylan, the following year’s huge blockbuster (with Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, The Who, Joni Mitchell, John Sebastian) was a very different beast both musically and in terms of scale.

On the Monday morning of September 1, 1970, Ron Foulk, promoter of the Isle Of Wight festival, announced: “This is the last festival. Enough is enough. It began as a beautiful dream but it has got out of control and become a monster.”

He was actually talking about the serious crowd trouble that plagued the island that year. But he could just as easily have been talking about the dreams of so many small-time, unknown bands who were once able to look to the summer and think: “This year maybe it will be our turn..."

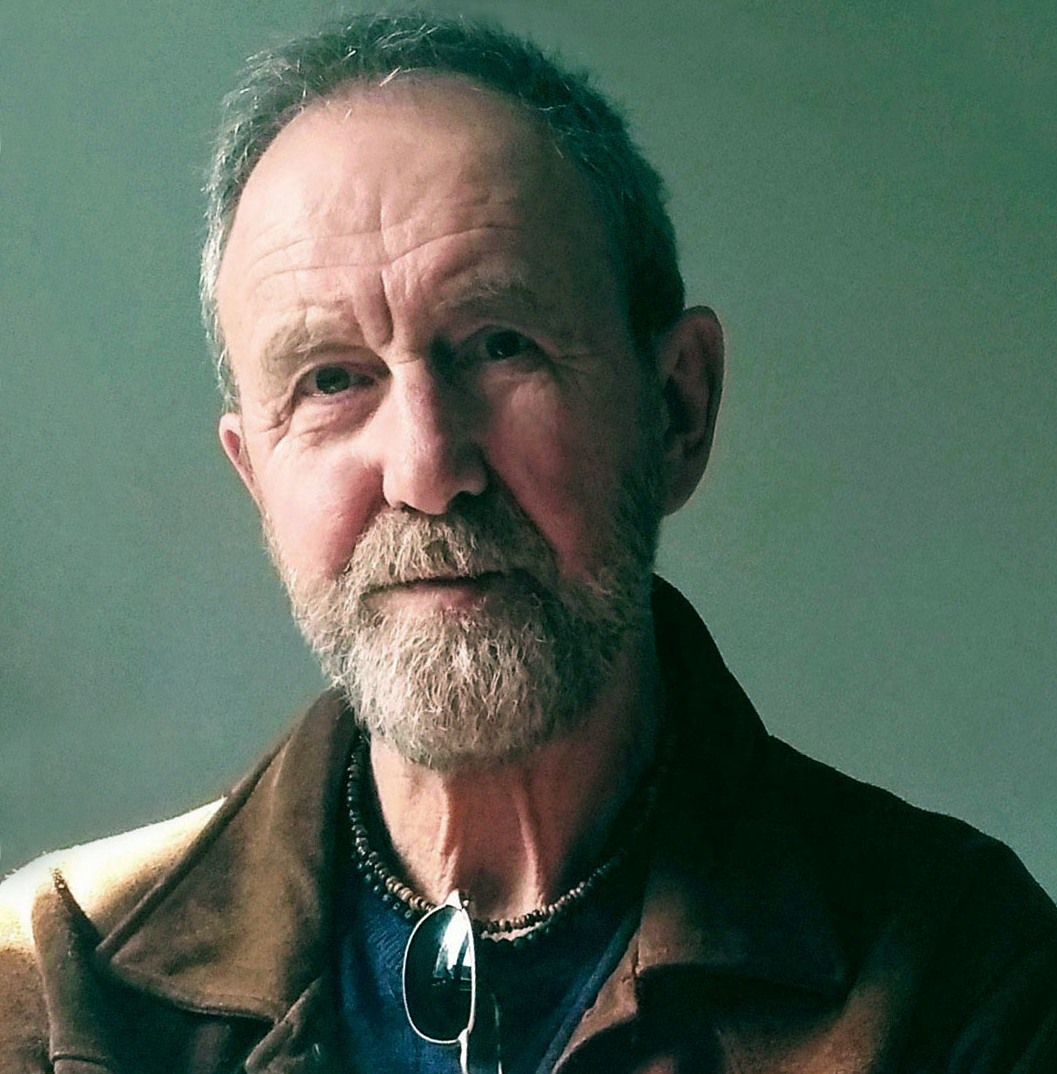

Classic Rock’s production editor for the past 22 years, ‘resting’ bass player Paul has been writing for magazines and newspapers, mainly about music, since the mid-80s, contributing to titles including Q, The Times, Music Week, Prog, Billboard, Metal Hammer, Kerrang! and International Musician. He has also written questions for several BBC TV quiz shows. Of the many people he’s interviewed, his favourite interviewee is former Led Zep manager Peter Grant. If you ever want to talk the night away about Ginger Baker, in particular the sound of his drums (“That fourteen-inch Leedy snare, man!”, etc, etc), he’s your man.