“Was air-drumming even a thing before Tom Sawyer?”: Neil Peart’s greatest moments with Rush

It wasn’t easy, but we’ve boiled the professor of prog’s most powerful percussive performances down to 10 key tracks

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

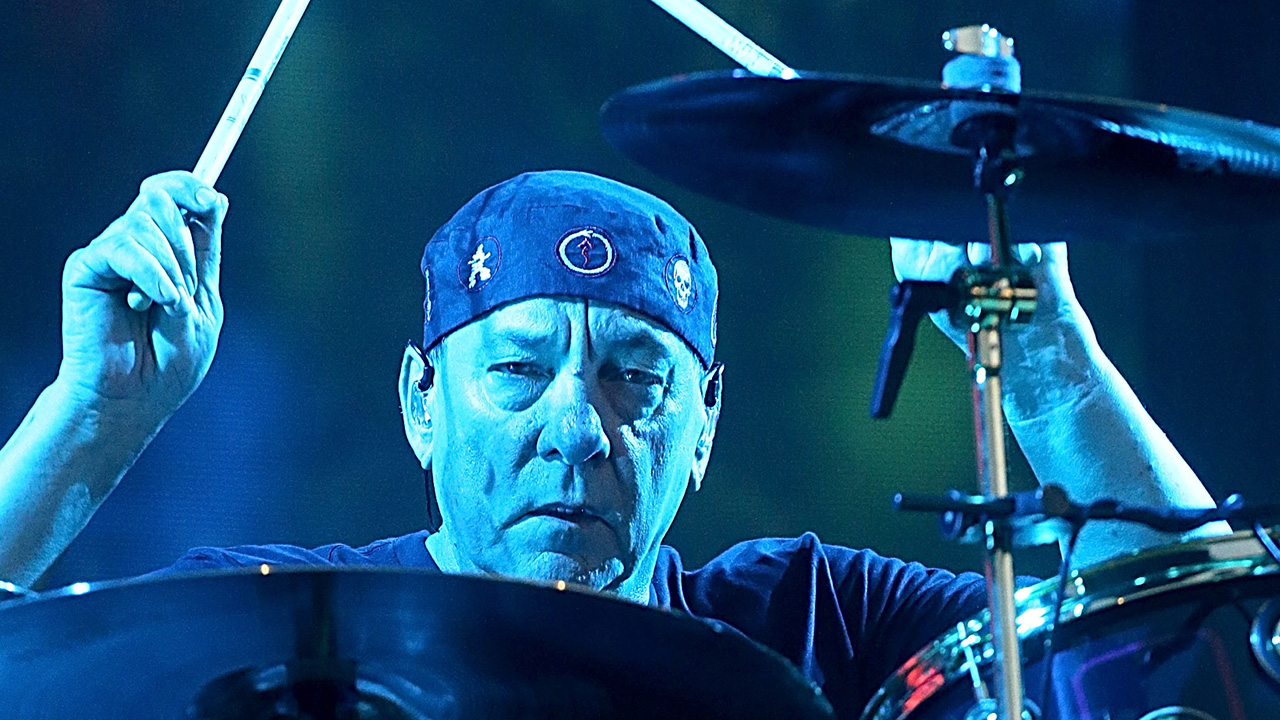

He was influenced by Ginger Baker and John Bonham, but Neil Peart’s playing style expanded with his impressive drumkit. A visionary and inspiration to many, he had a significant impact on Rush and the drumming world over five decades. In 2020, drummer and Prog writer Gary Mackenzie explored Peart’s legacy and unearths 10 highlights from his career behind the kit.

By-Tor And The Snow Dog (Fly By Night, 1975)

Few live rock shows saw open displays of air drumming quite like a Rush concert. And the reason was the high regard in which drummer Neil Peart was held by the band’s legions of fans. Almost as soon as he joined the group he made an impact: the colourful, lyrical impact of 1975’s Fly By Night matched the awe in which fans delighted in his drumming prowess. It was an awe and admiration that would last throughout the band’s – and beyond.

Alongside album opener Anthem, By-Tor And The Snow Dog announced Peart’s arrival in the most audacious and adventurous manner possible. He’s all over the first four minutes of this tune, throwing out bewildering fill after fill as if his life depended on it, matching guitar and bass unison figures note for note.

His playing often feels like it’s about to crash and burn while never quite doing so. It’s vital, energetic work from a clearly gifted young player who has unwittingly just set himself and his new bandmates on the path to becoming rock legends.

Xanadu (A Farewell To Kings, 1977)

Deliberate efforts to extend the band’s musical horizons and sound palette on gave Peart licence to break out an assortment of traps, toys and instruments. Xanadu sees him utilising tubular bells, temple blocks, wind chimes, glockenspiel and cowbells alongside his already expansive drumkit, in a gloriously epic interpretation of Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan.

He navigates the sections in 7/8 with confidence and dynamism, throwing in some truly inventive and punchy fills, and yet maintains a studied sensitivity to everything going on around him. A landmark performance for both the band and Peart.

La Villa Strangiato (Hemispheres, 1978)

Where to start with this nine-minute opus? How about the beguiling intro that just grows and grows? Or perhaps the sublime journey in 7/8 through the A Lerxst In Wonderland section, with Peart building from a rhythmic whisper to a percussive roar? Maybe the referencing of Raymond Scott’s 1937 tune Powerhouse, used in innumerable Warner Bros cartoons?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

What about those little jazz breakdowns? The stupendous fills? The turning- on-a-dime shifts in feel between different sections? The quirkiness and clear embrace of its own absurdity? This is a drum part so demanding that even Peart gave up trying to record the whole thing in one go.

Jacob’s Ladder (Permanent Waves, 1980)

Other tracks on Permanent Waves undoubtedly deserve attention: The Spirit Of Radio, obviously, and the terrific Freewill and Natural Science. But Jacob’s Ladder stands out for its slightly darker, quasi-classical elements, and because it’s metrically quite tortuous.

Sections in alternating 5/4 and 6/4 time, then the same phrases played by Peart and Alex Lifeson over Geddy Lee’s 4/4 vocal/keys part, a bit of 4/4 then alternating 6/8 and 7/8 bars, a few bars of 3/4 and even a solitary bar of 13/8 near the end make this an exercise in concentration. Add in a bit of timpani and tubular bells for a clever and rather classy drum part.

Tom Sawyer (Moving Pictures, 1981)

The quality and range of Peart’s drumming here makes it difficult to limit our choices, but we’ve settled for two. Tom Sawyer is a swaggering, gut-punch of a tune, propelled masterfully as Peart builds craftily through the verses before hitting you with big main themes.

When Lee and Lifeson hit the sections in 7/8, he shifts into playing what are essentially two bars of 7/16 to every one bar of theirs. And then there are those awesome fills – bombastic, thunderous and quite brilliant. Was air-drumming even a thing before Tom Sawyer?

YYZ (Moving Pictures, 1981)

Taking the rhythm for its opening 5/4 theme from the Morse code for Toronto Pearson International’s three-letter airport location identifier, Grammy-nominated instrumental YYZ packs some serious heft, dumbfounding stop/start action, intricate interplay between the band and marvellous moments of trading bass and drum solos. Delivering more in just over four minutes than many bands manage on entire albums, Peart is absolutely in the driving seat here.

Territories (Power Windows,1985)

No chaotic flurries around the kit or brain-melting odd-time signatures or furious, up-tempo pummelling – so what’s Territories doing here? It’s Peart building a part which, while hardly flamboyant, is quite involved and far from easy to play with any consistency.

It avoids the standard rock hi-hat/snare/bass drum approach, opting instead for a handful of repeated patterns utilising toms, snare, cowbells and a smattering of electronics. Peart plays for the song, explores possibilities and refuses to churn out what many might have expected of him. It’s a terrific drum part, and those 80s synth hits are undeniably magnificent.

Dreamline (Roll The Bones, 1991)

This is an example of Peart picking up the band’s early 90s ethos of being more direct and playing lean and mean. There are some terrific fills, especially towards the end – but the part’s main purpose is to provide focus and motion.

His playing suggests an underlying frantic urge to move onward, to boldly go, to not get stuck, to exist in the now and to leave baggage behind. Being the rhythmic engine here, he captures the sense both of the song lyric and the themes of Roll The Bones as a whole perfectly.

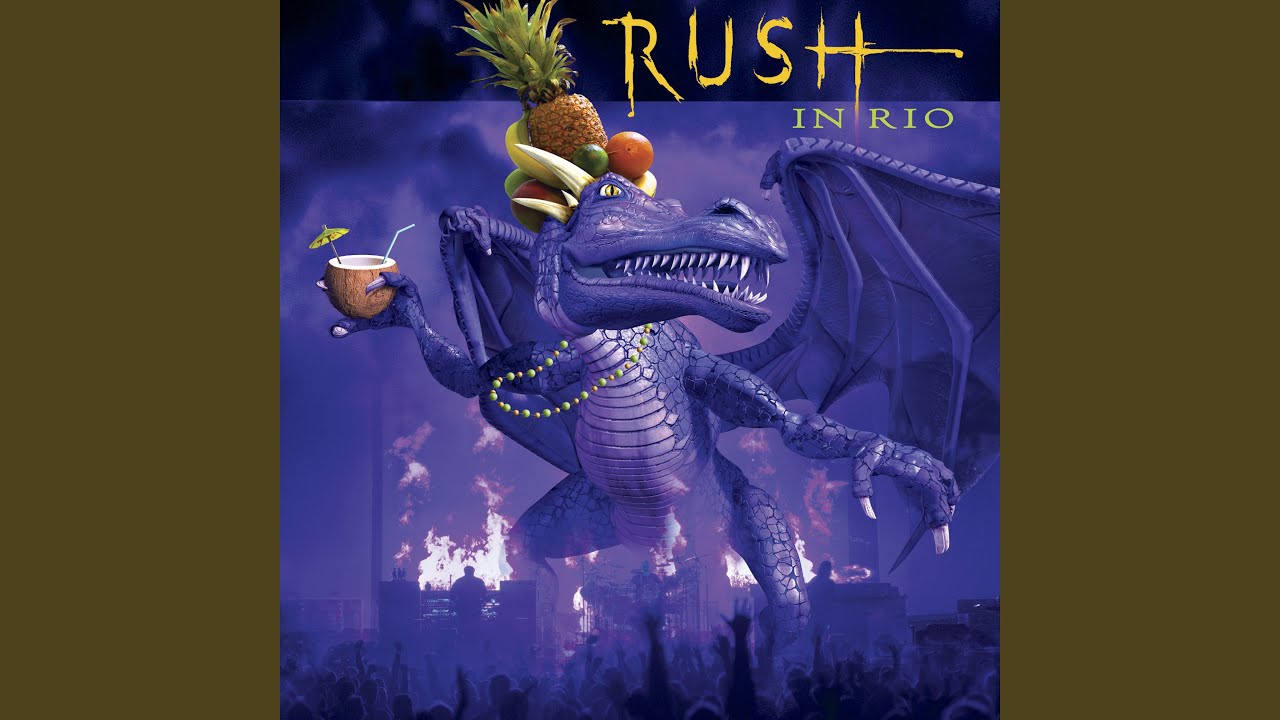

O Baterista (Rush In Rio, 2003)

Out of so many iconic Peart drum solos, this one, recorded right at the end of the Vapor Trails tour in 2002, is exemplary. He delves into every nook of his vast acoustic and electronic set-up, plays curious little ditties on marimba synth, improvises against a repeated foot pattern in 3/4, cleverly throws in snippets of past solos, and rounds it all off with a joyous playalong section to Count Basie’s One O’clock Jump (as recorded by the Buddy Rich Band).

Decades of his personal evolution are distilled into nine minutes and greeted with true love from one of the largest audiences the band ever played to.

The Garden (Clockwork Angels, 2012)

The closing track from Rush’s final studio album places a largely overlooked aspect of Peart’s playing under the spotlight. While much of Clockwork Angels harks back to rockier, guitar-weighted compositions – and boasts possibly the heaviest drum sound ever featured on a Rush album – The Garden also demonstrates his musical intelligence.

There’s nothing from him at all for the first minutes, and when he enters he’s not particularly outlandish. The craft here is knowing when and how to support the song; and the gradual build in intensity from the guitar solo through to the tune’s denouement is masterful. The rather beautiful lyric resonates more deeply now than it did at the time.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.