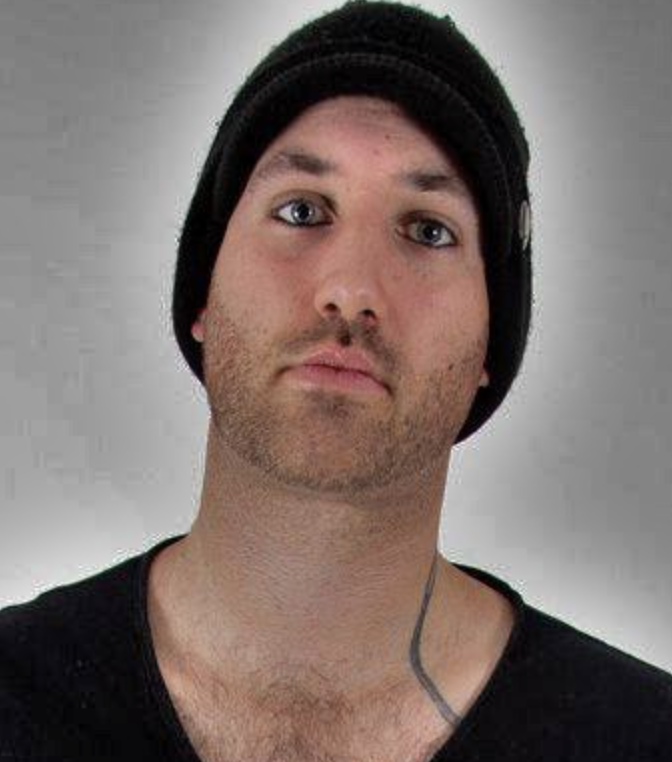

Jerry Cantrell: “I always held out hope that I’d go back to Alice In Chains”

Alice In Chains guitarist Jerry Cantrell looks back on the highs and lows of his career

It’s not very grunge to talk about yourself and your achievements; the Seattle scene that birthed so many icons is characterised by its down-to-earth, unshowy nature. As such, Jerry Cantrell, Alice In Chains’ guitarist/vocalist, is an affable but humble interviewee. “I just go where the music takes me and with what feels right,” he tells us. “And right now, it’s taken me to a new solo album, where I got the chance to play with my friends and a bunch of people that I’ve never played with before.”

Featuring contributions from Guns N’ Roses’ Duff McKagan and ex-Dillinger Escape Plan frontman Greg Puciato, Jerry Cantrell's third solo album Brighten is another milestone in an impressive career that began in 1987, when Jerry co-founded Alice In Chains. Thanks to the hype around grunge and the success of anthemic single Man In The Box, the band’s rise was meteoric, and they cemented their legacy with 1992 album Dirt. Tragically, they slowly self-destructed, with frontman Layne Staley passing away from a heroin overdose in 2002.

By this point, Jerry had embarked on his solo career, and no one expected to see Alice In Chains again. But in 2006, they reformed with new vocalist William DuVall, leading to an unexpected yet inspiring second act. Meanwhile, Jerry has collaborated with artists from Elton John to Metallica, and has flirted with the film world, appearing in Deadwood: The Movie and working with director Cameron Crowe on Singles and Jerry Maguire. One thing’s for sure: he’s come a long way from his “little town” of Seattle.

When did you get introduced to music?

“We used to play a lot of country music in our house, and so that was when I was first exposed to that. I could give you a list of about 50 artists, they’re all the old classics, and that was a big thing for me. My mother also played organ, so there was that, plus [performance/dance TV show] American Bandstand and AM radio, Cat Stevens, the Bee Gees – there was a whole mix of stuff going on in my house.”

Who were the artists that inspired you as a child?

“Elton John and Fleetwood Mac were big awakenings for me, as far as songwriting and what that meant and getting the magic of what that was. This was when I discovered the guitar as well, so there was AC/DC, Iron Maiden, Kiss and Priest… it was a huge time to be a music fan.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The first album you ever owned was 1974’s Elton John’s Greatest Hits, and then he ended up on your comeback album, Black Gives Way To Blue, in 2009. That’s quite an amazing story…

“Yeah, that’s true. My dad gave me that album. It’s one of those surreal, full-circle moments where this guy that was so influential to you ends up playing your song on his piano with you. He’s a fantastic man, a good hang and a fan of music – he’s a lifer. It’s all I ever wanted to be, to be someone who wrote music that people wanted to listen to, and he’s definitely that guy. An amazing talent and a beautiful human being.”

Do you remember the first time you held a guitar in your hands?

“My mother got me my first guitar. She was dating a guy at the time and he came over to jam with her. They were playing some tunes – she was on the organ and he was on the guitar – and I think I picked up a tennis racket and was miming air guitar with them.

He was like, ‘Does he play guitar?’ and she said, ‘No’, and he got me over and showed me a few chords and I picked it up straight away. He said to her, ‘Maybe you should get him one, he looks like he’s into it!’ She got me a little Spanish nylon string guitar, but it wasn’t until I got an electric guitar until it really kicked in. When I could hit that distortion and crank it up I really felt the power.”

You were childhood friends with Pantera’s Abbott brothers, Vinnie and Dime, which is crazy to think knowing what you all went on to achieve, isn’t it?

“Yeah, we had pretty similar career arcs. I went to college, really just to give me more time to fuck about and play guitar, and a few buddies of mine started a band. We never really played any shows, but the drummer decided he wanted to quit college and go to Texas for a year. I thought that sounded pretty good, so I quit halfway through my first semester and moved to Texas.

“We used to hang out in Houston and Dallas. There was a club called Cardi’s [in Houston] and lots of bands played there, and one night Pantera came through and I met those guys; I wanted to because they were so great. I was hanging with Vinnie, Rex and Dime, this was before Phil [Anselmo]joined the band, and I’m like half redneck and half Yankee – I was born in Washington but my Dad is from Oklahoma – which meant I got on with those guys really well. We had the same interests and the same dreams; it’s pretty crazy to see how our lives went.”

What was Seattle, and the Seattle scene, really like during the grunge boom period of the early 90s?

“At first it was just a lot of really great bands; I think anyone from any scene would tell you the same story. It was kind of unusual because there was a group of us that all took off together, but it was just our little town. The cool thing was that we would all hang out together.

It’s a big small town, there weren’t a whole lot of places to play – skating rinks, parties, garages – there weren’t many clubs. None of us were big enough to play the theatre, but it was really cool. There were a lot of young people who had similar goals of being in a rock band and we’d all go to each other’s shows. It was a really supportive and nurturing place.”

Was it odd when the big labels and the media came calling?

“For sure, by the time Soundgarden got signed by A&M, Mother Love Bone got signed [by PolyGram] and then we got signed by Columbia; it rolled from there. At some point the entire world became aware of our little town and it was different after that. We were all happy just to sell out the Central Tavern and then… it’s hard to put into words. We were just a little town and we were suddenly being looked at by people that we never could have imagined would even know we existed.”

Your connection with Layne, the way your voices melded together, was such a huge part of Alice In Chains. How natural and easy a connection was that?

“Layne was just an amazing talent. He had a real unique and powerful voice, but he had a sensitivity and touch to it as well. The way that I wrote and the way that he wrote blended together so well, we felt like a natural fit. He had more horsepower than me, I’m not going to be able to do the Brian Johnson gargled razor blades, but together we had something that the other didn’t.

Think of The Beatles, Pink Floyd, the Eagles... that attitude of, ‘You take this line and I’ll take that one’ – it adds more colour to the canvas. Someone reviewed us once and called us ‘The Satanic Everly Brothers’, which I thought was pretty cool.”

The legacy of 1992’s Dirt as a classic album, and one of the darkest albums in history, is set in stone at this point. How do you feel about it today?

“Well, dark… it is what it is. It’s probably the most focused we’ve ever been, the most complete record we’ve made, it’s a brutal record with some real force, and I mean that in a very good way. People cared about it, it spoke of a time and a place, we really never pulled any punches. Which is good and bad; it’s good artistically, but it’s bad because if you are going to be that honest then you’ll struggle to live it down. It’s an amazing record, it’s probably our crowning achievement.”

1994’s Jar Of Flies was the first EP ever to top the Billboard Top 200. That’s an incredible achievement.

“Yeah, it’s pretty wild. We had this idea between Facelift and Dirt that we had these acoustic songs kicking around, and we were known for more powerful and hard-hitting stuff, and that became Sap, which we thought of as a little Easter egg for the fans. So, we decided to do it again between Dirt and the self-titled album, and that was Jar Of Flies.

“In a lot of ways, it’s maybe become as definitive to our career as Dirt. A lot of people really liked that EP, the only one to have ever hit No.1, it’s pretty wild. We knocked Mariah Carey off of the No.1 spot – sense of pride for us! She was married to Tommy Mottola, who was the president of our record label, so I’m sure that was a fun night in their household that week! Mariah going, ‘Who the fuck are these guys?!’ Ha ha ha!

It was just a good five- or six-year window where rock was king, and that doesn’t happen that much, when you get even the pop people celebrating rock and it being the number one thing. It was probably the last time that happened.”

The 1995 self-titled record also got to No.1, but that was a difficult time for the band, wasn’t it?

“Well, we didn’t get the chance to tour that record, so we missed out on that opportunity. There were some really important songs on that record – Grind, Over Now, Heaven Beside You – and we never got to play them because we were coming apart at the seams. There is a real melancholy to that record because I don’t think any of us knew where we were going, it wasn’t looking good, and it proved to be our last record as that line-up.”

And the songs that became 1998’s Boggy Depot were ideas for the next Alice In Chains album, right?

“I’m always writing, always, so I’m sure some of those riffs and those ideas were things that I was going to be bringing into the Alice camp for whatever we were going to do next. But not everything works for this band, we have things that we bring in that aren’t strictly right – ‘I don’t know if that’s right, I don’t know if that’s Alice’, you know? But, since we weren’t going to tour, and it didn’t look like we were going to tour for a while, I took the chance to make the record.

“I was lucky enough to have the support of Sean [Kinney, AIC drummer], otherwise I probably wouldn’t have done it. He’s my best friend and my confidant in this band, so it was important to have him onboard. And Mike [Inez, bass] as well. I got to invite a bunch of my favourite friends and bassists down, [Pantera’s] Rex Brown and [Primus’s] Les Claypool, as well as Inez, so it was great.

It scared the hell out of me, though! I’ve never been the guy at the front and centre of the stage and that is really by design. It was a change, but I think it was a good thing to do, because it’s a really interesting and cool rock record.”

Presumably Alice In Chains were still a band in your mind, even if you were inactive?

“Yeah, I mean the plan was always to go back to Alice… I always held out hope. But you’re also aware it can go the other way; bands aren’t built to last, man. Those bands who last 30 years, you know they are the outliers and you know how hard it is to keep putting it back together again and again. So, I knew that there was a very good chance that we had reached that end point.”

What was it like stepping back onstage with Alice In Chains when you reformed in 2005?

“We did it in Seattle for a benefit for the [Indian Ocean] tsunami back when that happened. It was inspiring to see people help human beings that they didn’t know. Imagine that; we could use a bit more of that these days. We kicked around the idea of what we could do, and we thought that this would be a good way to do it, it’ll be weird and tough, but fun, and it’ll be for a good cause.

“We got together and invited some friends and we did it, and it was all of those things, really tough, hard, weird, sad… but also really cool. At the end of it we started thinking about maybe jamming with each other a little more. I invited William [DuVall, current AIC singer] down, because I’d done some stuff with him on [second solo album] Degradation Trip, and it snowballed from there.

The second half of our career is completely different from the first half, but it’s pretty much the same at the same time; we go back to the very start of this interview, you go where it feels right. You’ve walked these roads before, and your brothers have been there with you, and when time comes to celebrate, you do it with your fucking buddies. You can’t lose that way; you did some stuff, you did it with your friends, you stuck to your guns and some people fucking responded to it and they still stick with you today.”

Of all the guest spots that you’ve done, have you got a personal favourite?

“When Chino [Moreno, Deftones] asked me to play a solo on Phantom Bride. He sent me that tune over and I liked it and I threw him over some ideas, which he thought were really cool. I went down to the studio and it was really emotional and heavy in a really cool way. Seeing him respond to having me in there, and having him direct me, it worked, and it was an important moment. I dig those guys, they’re really talented. I really dig that Danzig album that I was on [1996’s Blackacidevil], too!”

You’ve had a fair few acting roles. Surely you’re the only alternative rock artist to have been in an Oscar-winning film, with Jerry Maguire? So, are you the grunge Marlon Brando?

“Ha ha ha! I’ve made a couple of cameos here and there; I really am interested in film, I’ve done a lot of soundtrack work as well, and that marriage fascinates me. But, grunge Marlon Brando? No, you’d have to give that to Gavin [Rossdale, Bush frontman]. If you’re going to pick a guy from my era who has made a decent career out of acting, then he’s probably the guy over me.”

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.