"We'd sit surrounded by amps. The magic just flowed. It gave you goose-pimples": How Status Quo made Hello! and turned into Britain's hottest band of 1973

Sometimes, a band works on an album and everything clicks. For Status Quo, their 1973 No.1 Hello! was just such an album. But that doesn’t mean there weren’t problems

Given what we know of them today, it’s ludicrous to apply the term ‘one-hit wonder’ to Status Quo. This is a band that has notched more than 60 hits at home in the UK, spending more than 500 weeks – almost 10 years – in the charts. And that’s just their singles. Nevertheless, from the success of 1968’s Pictures Of Matchstick Men, their first Top 10 hit, onwards, at several points in the band’s career the naysayers have thrown that undesirable tag at them.

To be fair, a succession of name changes, personnel switches and flop singles that preceded Matchstick Men had hardly marked them out as contenders for long-term stardom. And after following their breakthrough moment with another misfire, Black Veils Of Melancholy, it took a song by Marty Wilde and Ronnie Scott (not the famous jazz musician), Ice In The Sun, to return Status Quo to the public eye.

But Status Quo (or The Status Quo as they were still known then) were made of hardy stuff. Six years of hard graft were not going to be wasted.

The ditching of their Carnaby Street psychedelic clobber and the arrivals of guitarist/vocalist Rick Parfitt and road manager Bob Young, both of whom would contribute hits at key moments, helped to galvanise Quo, who dropped the ‘The’, grew their hair and wore the tattiest, grubbiest jeans. Twelve-bar boogie became the name of their game, performed with unapologetic zeal in dimly-lit pubs and clubs up and down the country. Audiences that didn’t appreciate them were advised to fuck off as the band packed up and drove to the next venue.

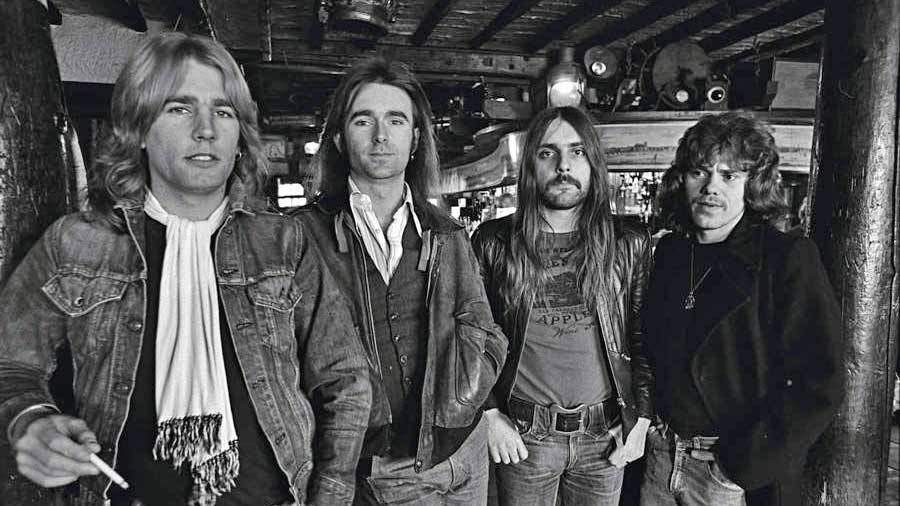

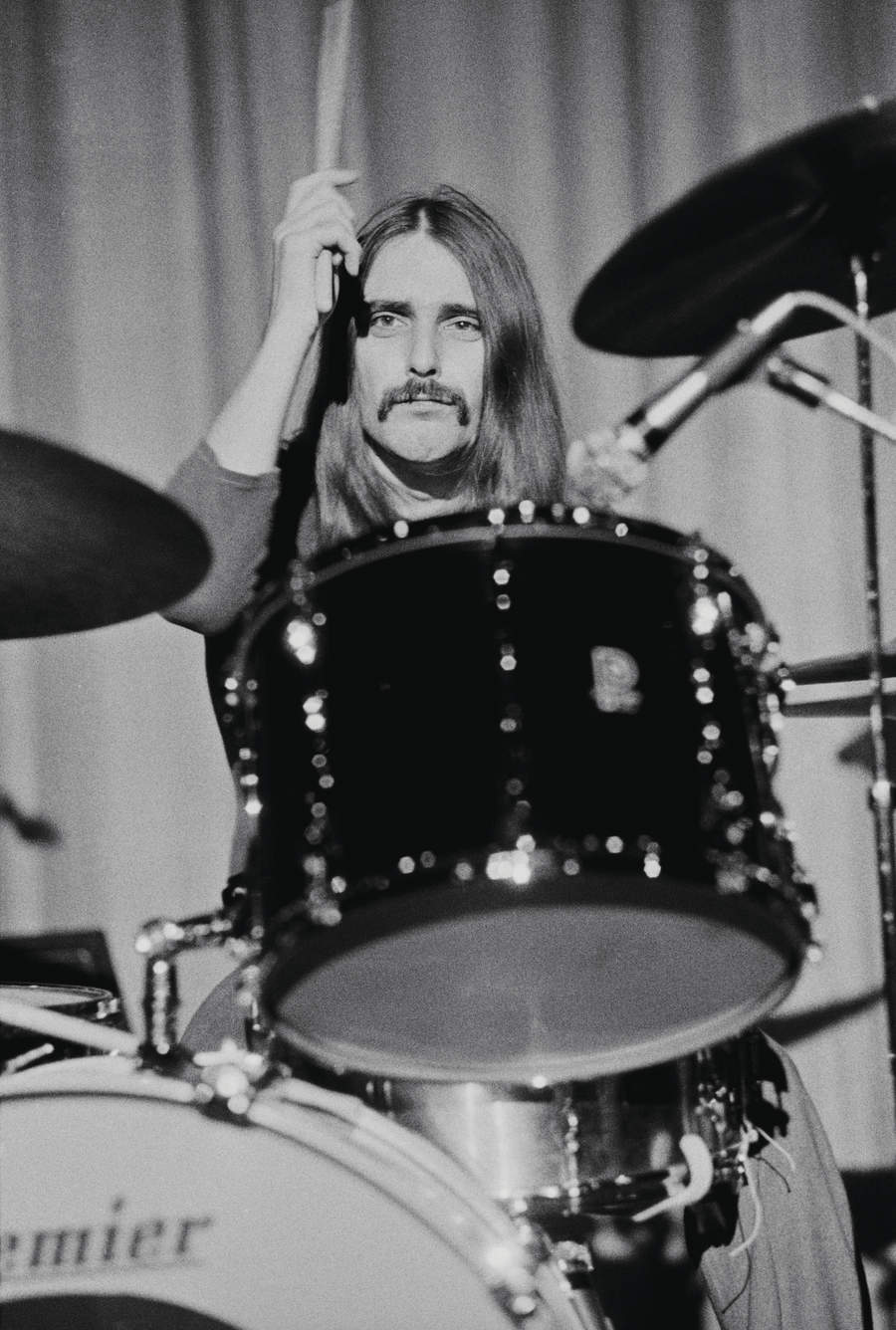

But many people did get off on Status Quo’s new direction, laid down on their third and fourth albums, Ma Kelly’s Greasy Spoon and Dog Of Two Head. Although neither of those troubled the chart compilers, and the group’s second keyboard player, Roy Lynes, ran out of patience on a train from London to Aberdeen in-between those two releases in August ’70 and November ’71 and left – thus reducing the line-up to lead guitarist/vocalist Francis Rossi, bassist/vocalist Alan Lancaster, guitarist/vocalist Rick Parfitt and drummer John Coghlan – against all the odds an unlikely industry buzz began to grow.

With sympathetic backing at last, and in spite of an entanglement with Pye Records, their manager Colin Johnson persuaded Phonogram Records boss Brian Shepherd to sign Quo to his hip imprint Vertigo. Shepherd handed over a budget of £30,000 and entrusted the quartet to self-produce an album with just an engineer, Damon Lyon-Shaw, and his assistant, Richard Manwaring. The result was Piledriver, an album that matched its title with a shrewd distillation of tight, hard boogie and hook-friendly melodies. Its turbo-charged anthem Paper Plane returned Quo to the Top 10 of the singles chart, and the album climbed to No.5.

Within months Quo went from a support band to headlining two nights at London’s celebrated Rainbow Theatre, and even testing the waters for the first time in the US (where they shared stages with, among others, Savoy Brown, Canned Heat, Manfred Mann’s Earth Band and Blue Öyster Cult), Australia and New Zealand.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Such mental fortitude and sheer will to overcome was little short of remarkable. But then just six months later, Status Quo had to do it all over again, or face the fact that those who had dismissed them as a one-trick pony had been right after all. And there was absolutely no chance that was going to happen.

Vertigo sent the band back to where they’d made Piledriver, IBC Studios in Central London. The bunker-like, windowless facility, with its high ceiling, fostered an environment of hard work, and had been used by many of the world’s biggest stars including The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, The Who and the Small Faces. Quo would record all of their early-70s albums there.

Producing themselves again, and reunited with Lyon-Shaw and Manwaring for technical support, they began work at IBC in mid-April ’73 on what would become Hello!. The place was theirs for a month, with some ‘tidying up’ time put aside in the summer after a return trip to North America.

Francis Rossi: After Piledriver had taken off the way it did, with Hello! we set out to do the same thing but at a higher level. The sound improved somewhat, and the band were better through all of the time spent on the road. Yeah, we felt some pressure in making a follow-up, but there was this cocky confidence that came out of Rick and mainly Alan that really pushed us forwards.

Rick Parfitt: At IBC Studios we were pretty wonga-d – there was some smoking going on – but they were such creative times. All four of us were seeing things the same way. Life was fantastic back then. Our writing was prolific and everything was opening up for us. We would arrive at, say, one o’clock in the afternoon and leave the following morning, unaware if there was daylight or darkness outside. You just buried yourself in the place and got creative. Those sessions will stay with me for ever – we played so loudly together. Who gave a fuck about the clock? We were still young; time didn’t matter.

Alan Lancaster: The brilliant thing is that nobody could tell us what to do. The record company didn’t get a say. Can you imagine what their reaction to a song as over-the-top as Forty Five-Hundred Times [the album’s 10-minute epic] would have been?

Parfitt: We had a stockpile of great songs, many from the road, [but we also] wrote in the bath, on the loo… We were bubbling over with ideas. All of the licks had yet to be written, and we were finding them day by day.

Rossi: The super-confidence that came from Alan and Rick served us well at the time, but for me [ultimately] it proved to be… not nice. Alan almost saw us as ambassadors to Great Britain. He had that in him till he died. Status Quo was so important to him – overly important, in a way that it never was for me. But we went into the studio believing: “Yeah, we can do this.”

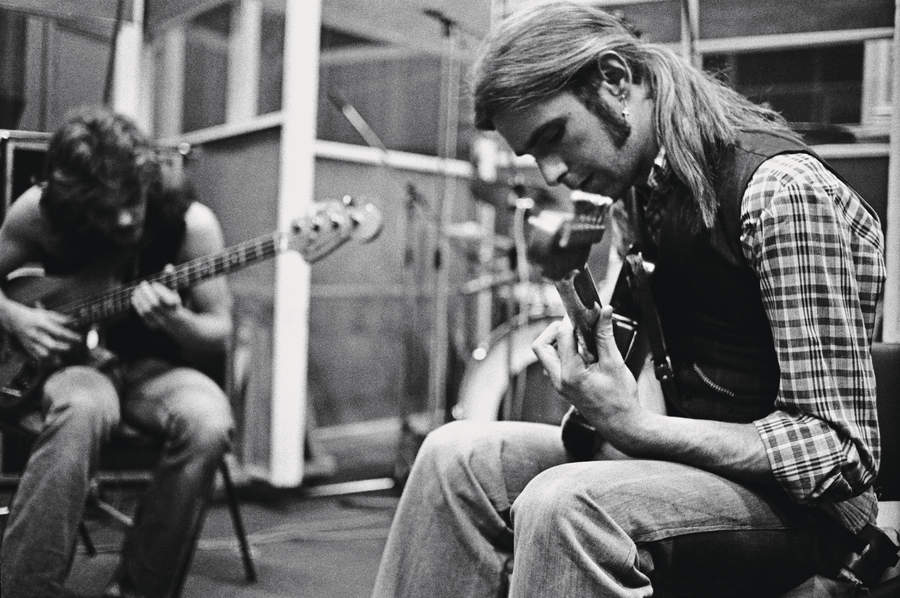

Photographs of Quo working at IBC during the early 70s show Rossi, Parfitt and Lancaster seated in a circle, in close proximity.

Rossi: That’s one of the reasons, good and bad, that the album sounded the way it did. Later on, when we did Rocking All Over The World, we worked the opposite way and everything was done in isolation. In theory, that’s the way you should make records. Listen to Caroline, and when the quiet part begins the compression [of the sound] comes up and you can hear the ambience around the kit, the guitars go ‘der-der-der-da-da-der-der’ [hums the riff]. You can hear the entire room. Then everyone comes back in. We were playing too loud. But having said that, the song still sounds great.

Parfitt: We played so loudly together that you became lost in the music.

Rossi: Playing together like that, able to stare into one another’s eyes, there was a real transference of vibe. That’s what happens now when I’m on stage with the current Quo. I love that we lock eyes again. But with Rocking All Over The World we were too far away across the room for that to happen, which wasn’t ideal.

Parfitt: The songs had all been learned, and we’d sit surrounded by amps. The magic just flowed. It gave you goose-pimples.

John Coghlan: An overriding memory of mine is that IBC studios was next door to the Chinese Embassy, and at times we received their Morse code signals through our amplifiers. It’s funny now, but we’d have to stop recording, so that was pretty frustrating.

Rossi: At that moment in time, Quo would have taken a bullet for each other. Alan and I had been together since we were twelve years old, and we’d known Rick since he was seventeen. John had been there since 1963. We’d been unfashionable, literally having to beg for gigs. I remember walking on stage at a gig supporting T.Rex at The Greyhound in Croydon and the audience turned its back on us. So we went: “Oh no, no, no…” and of course we’d win them over, which gave us a drive that in a way became part of the music.

Bob Young: IBC was Status Quo’s own Abbey Road, and it helped immensely that they had such a great team around them, from manager Colin Johnson to Brian Shepherd at Vertigo, and they had really tight crew of three or four people that were on-side with their every move.

With a thud that turns into a glorious chugging riff, Hello! begins via a genuine Quo rarity: a song written by all four members in association with road manager Bob Young, who besides being responsible for getting Quo from A to B also played harmonica on stage with them and co-wrote many of their biggest hits. Alan Lancaster remembers the group messing around with Roll Over Lay Down “on the piano backstage at gigs” long before it was recorded at IBC.

Lancaster: Songs are like a fine wine, they should be allowed to evolve. Where would that song have been without John’s tom-tom contribution? It was very much a band effort.

Rossi: Yeah, the band credit thing. Alan insisted he had written it with me, which of course he hadn’t. I got so annoyed that we credited everyone in the band. But really it’s by Bob and me.

Coghlan: It’s [built upon] four on the floor on the bass drum. Great fun to play live and it really gets the crowd going.

Rossi: The lyrics were about getting home from a gig early in the morning, and there’d be a note pinned to the door. ‘The drink cold from the fridge’ was a bottle of milk. It wasn’t about trying to get my end away. You’d be surprised how many people also think that’s what Down Down is all about.

Parfitt: A Quo show has always been pretty incomplete without Roll Over Lay Down.

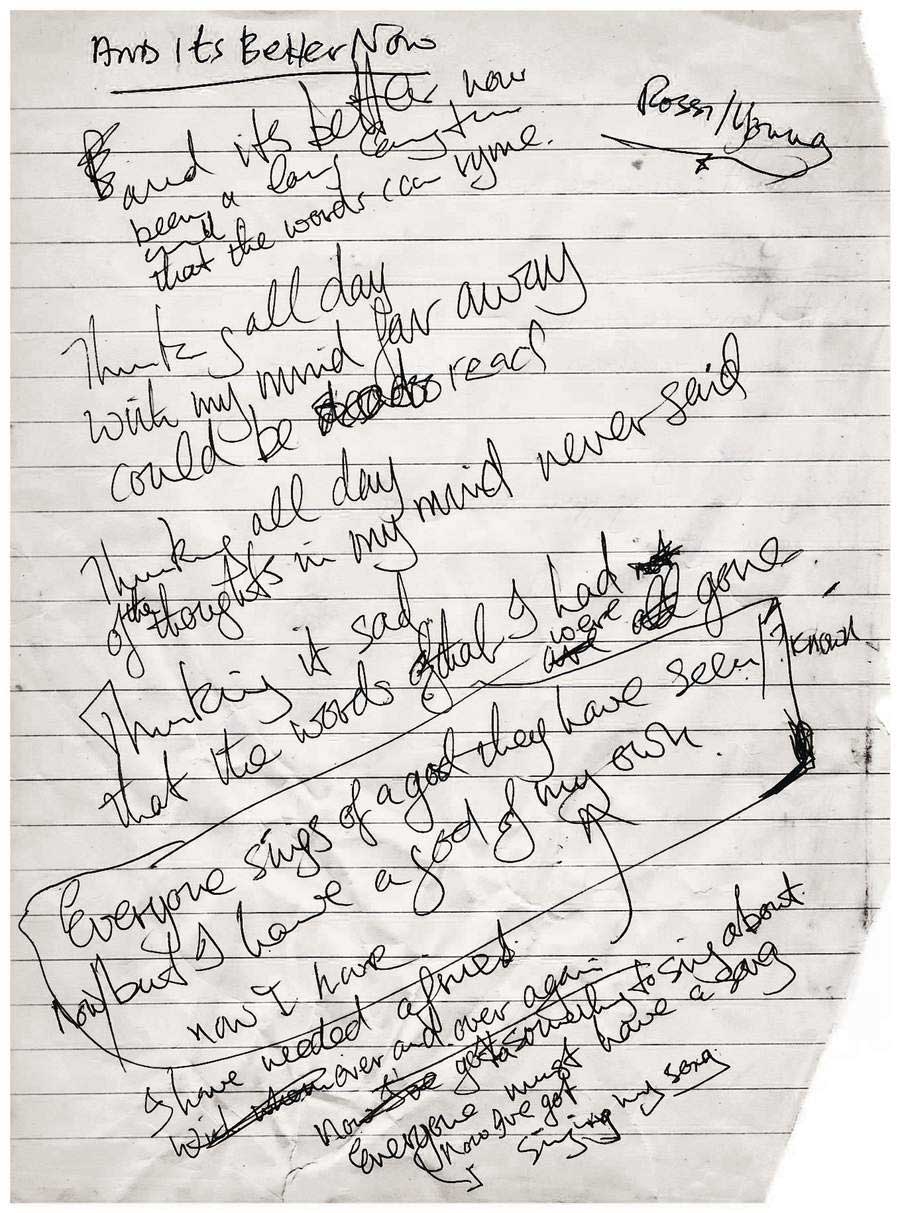

Excluding collaborations with others, the team of Rossi and Young wrote three of the album’s eight songs – Claudie, Caroline and And It’s Better Now, although the vexing subject of writing credits within Status Quo has bubbled away for decades. For example Softer Ride is officially a Lancaster-Parfitt composition, although half a century later Rossi still rues the omission of his name.

“Bob and I were writing so much together it really upset the rest of the band,” he explains. “Colin [Johnson] would often intervene with a political solution. I agreed to give it to Rick and Alan, when really it should have been the four of us.”

In fairness, Lancaster admits: “Rick and Francis had the basic idea, and I came in with some ideas of my own. Really, it should’ve been credited to those two as well.”

Fuck the paperwork, what a track Softer Ride is, beginning slowly then walloping in with a riff that’s right up there among Quo’s very best.

Parfitt: Quo have done quite a few slow shuffles, but after the intro Softer Ride is a really fast and powerful one. It’s such a turn-on… just magical.

Young: The subject of who wrote what within Quo, and also who didn’t, has been rumbling on for years. In a way it’s part of the band’s mythology. They worked by bouncing off each other. That’s where the magic came from.

Rossi: When Bob and I write together there are two books side by side. One is his, the other is mine. It works best when they overlap. ‘It’s so long since I sang songs for you.’ Yeah, I can see that in both of our relationships back then. ‘I’ve been living alone, in a house that wasn’t my home.’ That’s another tick. I think originally the chorus was: ‘England made a fool out of me’, but Bob picked the name Claudie out of the air and I fucking loved that. In my mind I was singing to my ex-wife. Bob may have been singing to all of his ex-wives!

Young: I’ve still got the original demo of Claudie, and it didn’t change much from how Francis and I envisaged it. Its roots came from the countryrock angle that the two of us liked so much.

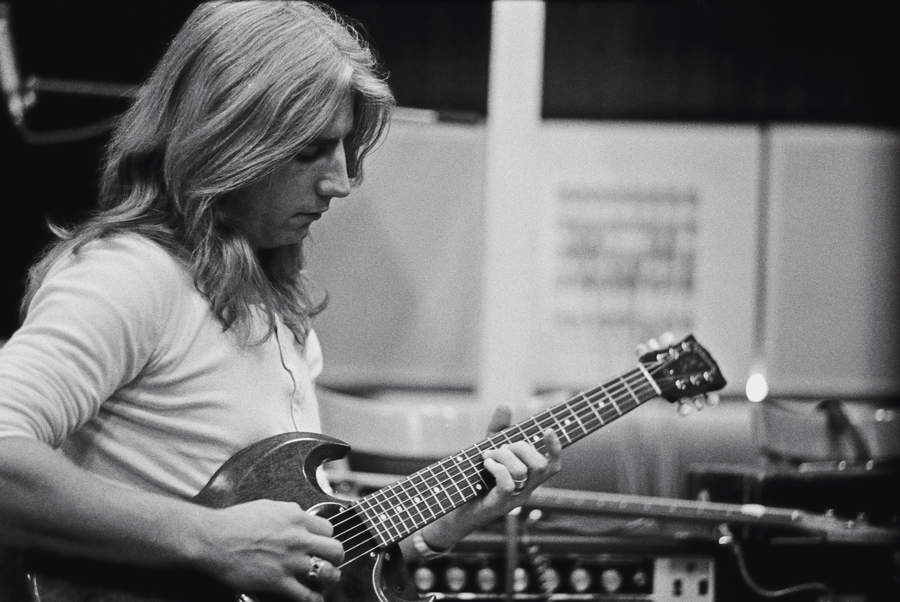

Rossi and Young had written Caroline in a country-rock stylée on a hotel restaurant napkin in Cornwall four years earlier, though its full potential wasn’t realised until the day in rehearsals when Quo toughened it up. One of their most identifiable and enduring tracks, it took the band into the UK Top Five.

Young: When we recorded Caroline at IBC the hairs on the back of everyone’s neck really went up.

Rossi: It had worked so well as a shuffle, but I still remember Rick playing the [opening] riff [the way it became famous] because there was a feeling of real magic. It’s such a good little melody.

Young: If there was such a thing as a light-bulb moment, it was Rick’s rhythm playing in the intro. He deserves the credit for that.

Coghlan: When Caroline comes on the radio, from the first few notes you know it’s us.

There’s a perception of Hello! as a heads-down-see-you-at-the-end album, but despite ticking all of those boxes it’s much, much more besides. Rossi and Young’s And It’s Better Now, with an intro that harks back to Quo’s early, psychedelic years, was a more understated moment. Listeners awaiting the arrival of a sledgehammer riff did so in vain.

Elsewhere, introduced by Parfitt crooning the words: ‘I felt in need for some loving, so I sat down on a wall/I tried to find a reason for living, but I couldn’t find a reason at all’ over a plaintive riff, A Reason For Living takes a while to bubble into full-bodied fruition. A poignant and reflective song, it was another reminder that, before its dissolution, the Rossi-Parfitt alliance invariably spelled greatness.

Parfitt: Those lyrics to A Reason For Living came from the heart. Some things were going wrong in my life and I was a bit depressed.

Rossi: That, to me, is when Rick was still Rick. He had such a great voice. The later stuff where he sang much more gruffly, that’s not Rick. I liked it best when he used his voice in that [more melodic] way; it was such a big part of the band’s early sound.

Parfitt: All these years later, that song still stands up, and I’m glad we re-did it on the acoustic album [Aquostic, 2014].

Young: You can hear that country influence on And It’s Better Now. Francis and I always loved that style of music.

Rossi: I remember watching a TV programme about a really sad little fellow who’d been sent to boarding school. When he said that he had a god of his own, I thought: “Fuck, I’m having that.” The riff ended up becoming the melody. I really liked it.

Blue Eyed Lady, once described by Parfitt, who wrote it with Lancaster, as “an outand-out rocker that was a joy to have performed on the Frantic Four reunion tours”, was the first of many, many Quo tracks that featured Andrew Bown. The former keyboard player with Peter Frampton-fronted 60s pop band The Herd, Bown would work with Quo on and off before eventually becoming a permanent member.

Rossi: It was my idea to bring in Andrew on that song. I’d met him and Peter [Frampton] when we supported The Herd, and I really liked him.

Andrew Bown: The Herd and Quo knew each other for years. I remember at an awards ceremony, Francis being jealous that The Herd had a roadie.

Rossi [indignantly]: They had this bloke that we had thought was one of the band. We were thinking: “Who the fuck is he?” It really rubbed me up the wrong way. So we got one too.

Bown: All the bands knew each other back in those days. But more importantly, The Herd’s management shared offices with Quo on Wardour Street.

Rossi: Later in life I find it less threatening to admit it, but I always liked that more feminine side [of rock music]. The thing that Freddie [Mercury] did. Andrew was somebody I thought I could work with. It broadened out the sound with one instrument. Andrew and I spent a lot of time working out keyboard parts and became very close.

Bown: I had almost forgotten that I had played on played Blue Eyed Lady. So listened to it this morning and, sure enough, two minutes and forty-seven seconds in, there’s piano [from me]. There’s a fuck of a lot of notes in that song.

Rossi: There are also two saxophones [played by Steve Farr and Stewart Blandamer] on that song but you can’t fucking hear them.

Forty-Five Hundred Times, the epic song that closes Hello!, is a triumph of light and shade. It begins gently before accelerating off into pure boogie-rock nirvana. The song became an instant live favourite, and was often jammed out to twice its original duration of fractionally under 10 minutes – sometimes even more.

Rossi: Forty-Five Hundred Times was worked on at my first mother-in-law’s house, a prefab. We were trying to write a song with three movements, like we later did with Slow Train [from the following year’s Quo]. Rick and I were in a bit of a Yankee phase, hence the title. In real English it would’ve been called Four Thousand Five Hundred Times, which doesn’t quite work, does it?

Parfitt: Truthfully, I don’t remember much about the writing of Forty-Five Hundred Times, because for a lot of the time I was away with the fairies.

Rossi: It was one of the last songs by me and Rick. Each time we thought we’d got something good, Rick would try to improve it and we’d end up losing track of where we were. It was like pulling teeth, which is among the reasons why we stopped writing together.

Parfitt: If something had potential, I always tried to make it better. Sometimes it worked, and others it didn’t, but I pushed things to the limit. That didn’t always sit well with Francis.

Rossi: I wish Rick and I could’ve continued, but it became too difficult. So many good things were lost when our egos clashed.

Young: Francis and I had a lot of involvement in that one, even though it’s a Rossi-Parfitt song.

Bown: You know, I think I played on Forty-Five Hundred Times as well as Blue Eyed Lady. They asked me to play in B and jam for about fifty bars. I remember that very well. I think I got paid for it.

Rossi: Yeah, he did. It needed that extra embellishment. How did we find John Mealing, the guy who was credited with playing piano? I really don’t remember.

Young: Recording the song at IBC was a real magic moment. When the band cooked in the studio it was every bit as exciting as when they went for in on stage.

The album’s title was suggested by the band’s manager, Colin Johnson. Its artwork also introduced a logo that, just like the silhouette of the group’s four members, guitars and sticks raised aloft, which graced its front cover, would decorate denim jackets and waistcoats for decades to come.

Released on September 28, 1973, Hello! displaced Sladest, by the band’s good friends Slade, at No.1 and spent 28 weeks in the UK chart. It was the first of Quo’s four UK No.1 albums. Emotions were mixed as they reached the summit for a second time. However, with Hello! all four band members knew they had created something special.

Rossi: Colin Johnson had so many brilliant ideas, and he didn’t receive enough credit for that. He was not only a manager. Colin re-mortgaged his house and did everything within his power to make Status Quo a success. He truly, truly believed in us. Each night, we’d walk on stage and I’d say: “Hello”, and he recognised the power of that.

Young: The cover’s simplicity made it so eye-catching. The silhouette and the logo said everything you needed to know.

Rossi: I did love the cover, but later on [in post-Spinal Tap years] I liked it a bit less for the whole ‘none more black’ thing [guitarist Nigel Tufnel’s infamous comment on the cover of his band’s Smell The Glove album].

Parfitt: At the time of Hello!, we were out on our own and we knew it. It felt as though Quo were getting bigger by the hour. We suddenly realised that we were the band of the moment. We really didn’t think that anyone could touch us.

Lancaster: It’s one of my favourite Quo albums, if not the favourite.

Parfitt: Hello! is my favourite of our albums and I love everything about it – the cover, the content, and also the fact that it took us to the top of the charts for the first time.

Coghlan: It’s classic Quo, isn’t it? There’s not a bad track on it, and most of them went on to become live favourites.

Rossi: Hello!? Nice record. Very proud of it. But I got over [the success] quickly and wanted to know what was next. There’s rarely any time to savour things. When they told us we were number one I probably replied: “Yeah, but has it done the same thing anywhere else?”

When a band becomes a chart-topper, that’s when the big numbers start kicking in – rocketing record sales and gig attendances – along with lots more waiting around in airports, groupies and drugs. Then they realise they need to make another album. Quo’s next record, the balls-to-the-wall Quo, was released just eight months later.

Rossi: Cocaine wasn’t an issue yet, and I’d gotten over groupies – I think we all had. The thrill of a record you’d made being played and enjoyed by so many people was what I appreciated. I loved the way records used to sell. Now, of course, music doesn’t mean as much. Coming out of Hello! and into Quo, that was a problem because they [Parfitt and Lancaster] didn’t want that shit that me and Bob had been writing.

Parfitt: Francis had drifted off in a different direction, a little more countrified. I wasn’t having any of that. I preferred hard rock. Nuff [Lancaster] is from the leather wristband-and-spikes brigade. I wouldn’t go that far, but like him I was a rocker, and I loved to write those harder songs.

Rossi: I’m not saying Quo didn’t contain some really good songs, though you knew [Rick and Alan] had been out watching other groups – mainly Deep Purple. But Hello! was such an important album for us, it affirmed we could get to number one. Now it was all about the next transition. It’s always been about chasing that carrot. I have nightmares about catching it, which would be a complete disaster. Catch your carrot and you’re fucked.

Rick Parfitt and Alan Lancaster were interviewed in 2015. They passed away in 2016 and 2021, respectively. The current lineup of Status Quo play European shows throughout the summer.

Dave Ling was a co-founder of Classic Rock magazine. His words have appeared in a variety of music publications, including RAW, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Prog, Rock Candy, Fireworks and Sounds. Dave’s life was shaped in 1974 through the purchase of a copy of Sweet’s album ‘Sweet Fanny Adams’, along with early gig experiences from Status Quo, Rush, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, Yes and Queen. As a lifelong season ticket holder of Crystal Palace FC, he is completely incapable of uttering the word ‘Br***ton’.