“You see people behaving properly and think: ‘I’d like to be part of the blowing of the whistle – even if it’s only writing a poem or a song or whatever”: Roger Waters changed tone, but not topic, on Is This The Life We Really Want?

2017 solo album saw him determined to look forward as he said escaping Pink Floyd was like “driving away from a dodgy wedding with cans dragging behind the car, rattling all the time”

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

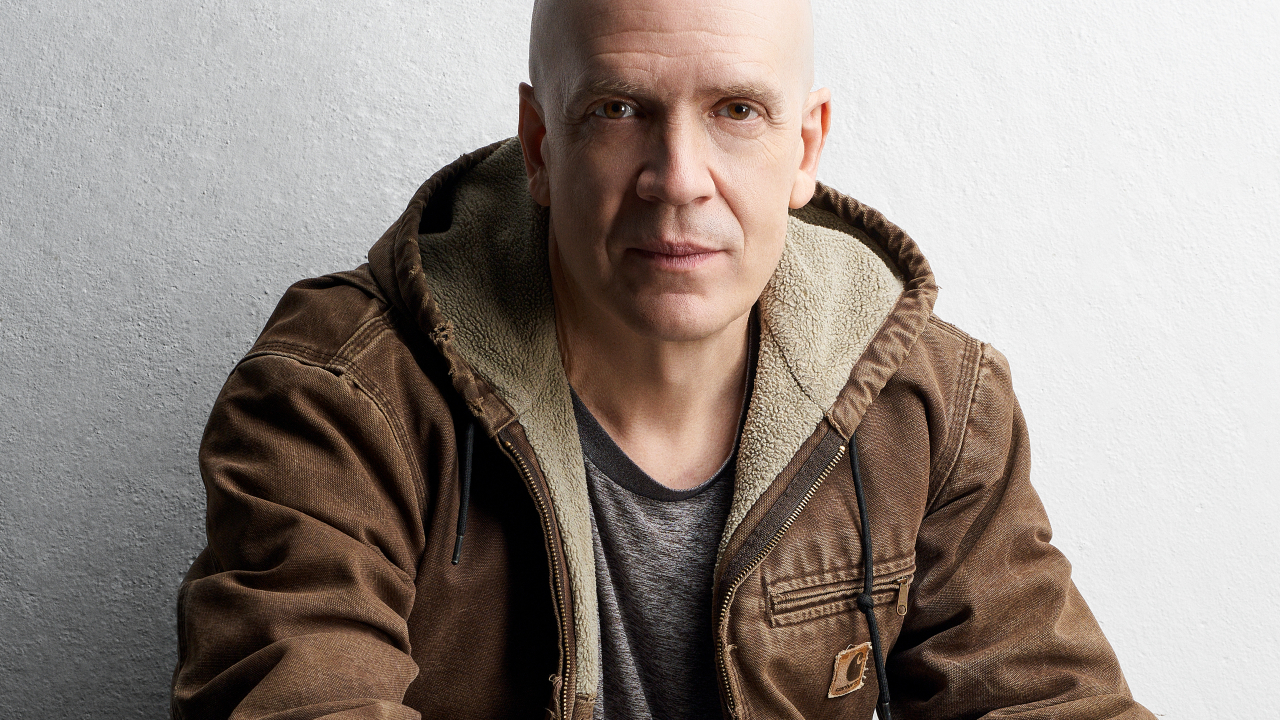

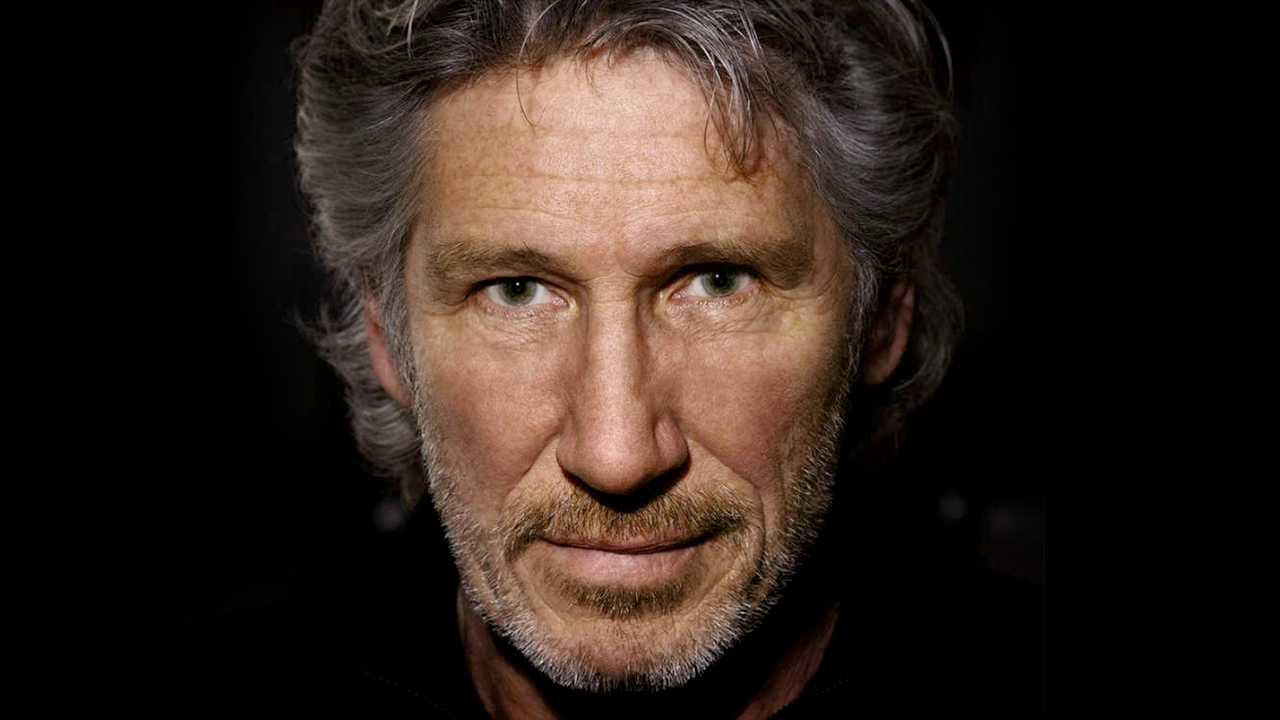

In 2017, as he continued trying to distance himself from his Pink Floyd past, Roger Waters was focusing once again on the state of the world. He told Prog about exploring the matter on that year’s release Is This The Life We Really Want? – his first solo album proper in 25 years.

It’s been nearly a quarter of a century since Roger Waters released his last solo album proper, 1992’s Amused To Death. In that time he’s become the top-grossing touring solo artist with his immense Wall spectacular, and even reunited with his old Pink Floyd buddies/sparring partners for 2005’s Live 8 concert in Hyde Park.

In 2010, when announcing his The Wall shows – which began in arenas and ended up in the world’s biggest stadia – he said: “I’m not as young as I used to be… But I still have a fire in my belly and I have something to say.” This is certainly true, seven years on, with Is This The Life We Really Want?, his fourth solo venture. As one might expect, he’s still an angry man, railing over some fine Nigel Godrich-produced music at the world around him.

Article continues belowHe remains exasperated at the injustice he sees on every level of life; his themes, let’s face it, haven’t really changed that much since his Animals-led tirade at humanity back in 1977. And the current caustic state of the planet gives the 73-year old plenty to rage at.

Yet there’s a sensitivity on the album that previously hadn’t surfaced in his output; and journalists of late have remarked on what a different man he seems to be from the one who’d tried to sue his old bandmates, incredulous they’d even consider carrying on without him. Of course, if you scratch that particular wound he’ll still bite – but as we saw at the launch of Pink Floyd’s Their Mortal Remains exhibition, it’s now handled with a slightly exasperated sense of humour.

So has rock’s greatest curmudgeon softened in his old age? Well, if you listen to the plaintive Wait For Her you might think so; it’s a love song sat amongst his tirade against the world we’ve created for ourselves. Waters is a man who hardly needs poking with a stick to vent his spleen, and the current state of the world gives him more than enough ammunition. And as we saw the night before we sat down with him, he’s in startlingly good form for what Prog’s reviewer pretty accurately calls an “irascible genius.”

“I think it’s the question of giving myself my due,” he muses. “You know that guy who asked me that question about having a judge on the shoulder? And I gave him a perfectly reasonable and fairly eloquent answer, because I know exactly the feeling that we all carry this judge around and it’s going: ‘Nee, nee, nee, nee.’

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“Particularly, though, in the aftermath of that Pink Floyd thing, which was hugely important. I was in that band for 20 years or whatever it was; but there was a lot of baggage. It was a bit like driving away from a dodgy wedding with cans dragging behind the car rattling all the time.”

All that crap about, “He wouldn’t let us write.” Nobody can stop you writing!

Did you feel you were made responsible for the break-up of Pink Floyd?

There was a huge amount of enmity, you know? And I will probably never be forgiven for all the work that I did, particularly by the other guys who were in the band. But we’re all dying, so who gives a fuck, really? It’s whatever.

It took me a while to get over that and stop worrying about trying to figure out what people had problems about stuff. All that crap about, “He wouldn’t let us write.” Fuck you! Nobody can stop you writing, dopey – or whoever you are. It’s ridiculous. I don’t want to get into it, because you can hear I feel quite jolly about it, but I’m just sick of it. I’ve left it behind me. I don’t usually talk about it because… And I won’t talk about it any more now. I’m done.

So you’re in a different state of mind these days?

Well, I had no idea that I was going to be able to succeed. Because I had had the whole Pink Floyd audience turn their back on me in 1987 when they started to tour again. I was playing to tiny audiences and there was a lot of, you know… bleurgh.

People certainly seem to have changed their minds about you. They’re certainly aware of who you are and what you do these days.

Yeah, they seem to have figured some of it out. And this record, I think, is helping them to figure it out; people who have heard the record, the whole thing, are going “Wow!”

You certainly make things clear on Is This The Life We Really Want?

Yeah.

When World War II was over, we could have been free – but we chose to adhere to abundance

But you’re also looking to the future, which is important.

It is, yes.

How many other musicians that are in their 70s are still making albums that make such salient and prudent points? You’re not just doing an album of old blues covers.

I’m not. Or Sinatra covers, like Bob Dylan! Bless him.

So why has it taken you almost 25 years to actually write and record a new studio album?

I don’t know. Like I said last night, writing the song Déjà Vu was a catalyst, a starting point for some of that. And also, as I say, I derived encouragement from the work of certain documentary filmmakers. I mentioned Jeremy Scahill and his movie Dirty Wars. And also the extraordinary fortitude and courage of Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden and Ray McGovern and Daniel Ellsberg and all the other whistleblowers that have emerged from the ashes of the Vietnam War.

"I know that was a long time ago, but one takes courage from all of that. You see people behaving properly and you think: “Wow, I’d like to be part of the blowing of the whistle,” even if it’s only be writing a poem or writing a song or making a record or whatever it might be.

Originally there’d been talk about the song Heartland being released in 2008. So you were already thinking about an album then?

Yep.

And some of these new songs date back to the 2008-2010 period?

Yes, they do. You know, there’s still lines in a song that I wrote back then, which I’ve still never recorded. There’s a line in it that sounds pretty cynical, but I kind of like it: ‘And the man who sold his kids for meat to a broker in Bangkok and got a colour TV, and the keys to the executive washroom and a space in the company parking lot.’

If you have to sell your kids for meat to a broker in Bangkok, Trump would approve of that. Or somebody else’s kids

That’s some nice writing, because it says a lot about commerce and how we become slaves to commerce, particularly in the US. But this, the idea of commerce being as important as it has become and spreading all over… the model, the American model. When World War II was over, we could have picked over them broken bones, we could have been free – but we chose to adhere to abundance. We chose the American dream, and that is the American dream.

And if you have to sell your kids for meat to a broker in Bangkok, Trump would approve of that. It’s business. Or somebody else’s kids. I mean, he might not sell his own kids, though you sense that they’re like lumps of meat when you see them parading around. They’re like prize cattle. They’ve sort of been plumped up. Those Trump boys, they look as if they’ve been injected with hormones every morning before breakfast to get them that pumped up and kind of dopey.

We don’t know that they haven’t been!

We don’t know, no. We don’t know.

You live in New York. What keeps you here in the Trump era with things so seemingly bad? Do you feel like the voice of opposition? Leading the resistance?

There’s a lot of people resisting this bullshit, luckily. It’s also convenience. I moved here because my youngest kid was here. And then I sort of stayed and I went through another marriage and stuff. And you gather the detritus of life around you and it’s easy to get stuck.

But I’m not unhappy here. And you can walk a lot of places in New York. I’ve recently taken to using the subway a lot, because it’s much faster than going anywhere in a car or a taxi. Actually, I like it on the subway. I like being kind of crushed – or not crushed. I often travel in the middle of the day, and it’s nice when there’s not many people there. But it’s nice to sit there and look at the other people. You see who lives in this city and how diverse it is; how cosmopolitan it is.

The poem is actually specifically about waiting for a woman to orgasm. I had no idea when I first heard it

The new album is also about love, isn’t it?

Yes.

Wait For Her reads like a manual for a better relationship. Like, “This is what I’ve got to do, and you’d better not mess up.”

Actually it’s very specific. It’s based on a translation of a poem by Mahmoud Darwish, the famous Palestinian poet. And the poem, in its title, has the words ‘Kama Sutra.’ It’s actually specifically about waiting for a woman to orgasm. I had no idea when I first heard it and when I started writing this song. And it’s beautiful. He is great… I knew nothing about him, and then I discovered him, and his poetry is extraordinary.

Then there’s a song called Broken Bones where you’re clearing your throat in the beginning.

I did clear my throat before singing one day, and Nigel just left it in. One does clear one’s throat from time to time when one’s singing!

Godrich is an interesting choice for a producer. You had a production hand in your three previous solo albums. What made you pass this time round?

I might have been tempted. I don’t really remember, but it feels good. I think he’s done a great job, so I couldn’t have made this album on my own. Well, I could have done, but it would’ve been completely different. So I’m really glad that I did relinquish control. I’ve never done it before. I may never do it again. But I’m glad I did it this once at least.

Last night you hinted that you’re already thinking about your next album. Is that because you’ve written so many songs over the years?

I’ve got tons and tons of material, yeah. And when I next make a record, I don’t know. I have to, at some point, release a recording of the other half of Déjà Vu which I recited a verse of last night: ‘If I had been God, I would not have chosen anyone. I would’ve laid an even hand on all my children. Everyone would have been content to forgo Ramadan and time better spent in the company of friends, breaking bread and mending nets.’