The story of Riot, the unluckiest band in the world

In the late 70s, Riot were the Great White Hopes of American rock. But that was before the public ignored them, their label disowned them, and their singer quit. And then things got really bad…

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This is a story of heroic failure. Of bad luck and lousy timing, misguided decisions and clashing personalities. Of a band who fell foul of the machinations of the music industry, the fickleness of the record-buying public and the dark side of the rock’n’roll dream.

The band in question is Riot, a bunch of New Yorkers whose determination to succeed was exceeded only by their repeated failure to do so. Between 1977 and 1981, they released a string of albums that should have turned them into superstars, one of which – 1981’s Fire Down Under – remains one of the great hard rock records of the era.

They’re fêted by everyone from Lars Ulrich, who has cited them as an influence, to Lady Gaga, who took inspiration from one of their anthems. They had the songs, the look and the determination.

What they didn’t have was the breaks. The Riot story has all the ingredients of a true heavy metal epic: the youthful dreams, the missed opportunities, the dogged perseverance, the repeated failures, the frustration, the farce, the bickering, the violence, the drugs… and the deaths of not one but three key members.

It’s Spinal Tap without the jokes; The Story Of Anvil without the happy ending. It’s a cautionary tale to anyone dreaming of rock’n’roll fame, and a reminder that for every band who make it, there are thousands who don’t.

“It’s just amazing that anything ever happened,” says drummer Sandy Slavin, who was a member of the band during their early-80s heyday. “When I played with Ace Frehley we’d be sitting on the bus and everybody would be telling you their music business horror stories. Mine was always just that little bit more horrifying."

“To be successful, you have to be a great performer, play the game and work with the press,” says Billy Arnell, who co-managed the band in the late 70s and early 80s. “Riot wasn’t that great at that stuff. They didn’t understand that being in the music business, a multi billion-dollar industry, took more than thinking like a Brooklyn kid.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Former guitarist Rick Ventura – a man who lived through the worst parts of the story – puts it more bluntly: “Talk about a band with bad luck.”

If one man was the driving force behind Riot, it was guitarist Mark Reale. A tall, skinny Montrose fanatic with thinning hair – which he later covered with a series of wigs – the unassuming but quietly ambitious Reale would be the only constant member throughout the band’s history.

It was Reale who founded the band in his native Brooklyn in the summer of 1975 with bassist Phil Feit, drummer Peter Bitelli and vocalist Guy Speranza. A wiry Italian-American with a striking afro-style hairdo, Speranza looked at first glance like the archetypal 70s rock god-in-waiting. But his unobtrusive manner suggested that he wasn’t necessarily cut out for a life in rock’n’roll.

“Mark told me that he had to talk Guy into joining the band,” recalls future drummer Slavin. “He was singing with a Top 40 band in Brooklyn – he could take it or leave it. Guy was very adaptable; he was like a blank slate. When he joined Riot, he became the singer of Riot. Whoever he was hanging out with, that’s who Guy was going to be.”

Like Speranza, Reale had served time in several going-nowhere teenage bands, serving up Humble Pie and Foghat covers to drunken schoolfriends at backyard parties. But Riot were different. Reale and Speranza were writing their own material, for starters. They knew they had more to offer; they certainly hoped they had more to gain.

In a taste of what was to come, their timing was atrocious. New York in the mid 70s was in the grip of disco fever: glitterball hedonism and white powder were the order of the day.

Elsewhere, the burgeoning punk scene had taken root at infamous dive CBGB, spearheaded by the likes of The Ramones, Patti Smith and Television. At that time in the Big Apple, if you were a rock band who weren’t called Led Zeppelin, you faced an uphill struggle to get noticed.

But Riot had what most other rock’n’roll hopefuls didn’t: a go-getting management team in the shape of Billy Arnell and Steve Loeb. Arnell was a chain-smoking hipster with a machine-gun repartee who wouldn’t have seemed out of place in the creative department of a Mad Men-style ad agency. The more laidback Loeb was one part hippy, one part hustler; as a kid he had run around with future Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley.

Over the next decade, Arnell and Loeb would play a pivotal part in Riot’s career – sometimes for the good of it, sometimes not. Arnell had carved out a career writing jingles for an ad company before teaming up with Loeb to buy a studio, Greene Street, in Manhattan’s SoHo district. They were looking for a band to launch to their new label, Fire Sign Records. Initially, they were keen to sign something edgy – a punk or New Wave band. But when they stumbled across Riot playing in a club in the summer of 1976, they instantly saw something in the fledging outfit.

“They sounded great, looked good and had some fantastic material,” says Billy Arnell today, before pausing to mutter: “Little did we know what was coming.”

In late 1976, Riot entered Greene Street with Arnell and Loeb to record their debut album, Rock City. As well as releasing it on their own label, the two managers opted to produce the record themselves – sowing the seeds of a clash of interests that would impact on the band further down the line.

The album took seven long months to produce, and was a disjointed affair, though it did contain a trio of cult classics in the shape of Warrior, Tokyo Rose and the title track. It also introduced the band’s mascot, Tior, a ludicrous axe-wielding half-human, half-seal hybrid that prompted as much derision as it did admiration, not least among the band themselves.

Released in late 1977, Rock City found little favour in a year dominated by Fleetwood Mac and Donna Summer, and it sank without trace in America (though it cause a stir in Japan).

Undaunted, the band started work on the followup, Narita. Produced once again by Arnell and Loeb at Greene Street, it was a vast improvement: the band sounded infinitely more confident, and it housed another terrific song in the shape of future live staple Road Racin’. But by now, Riot were even more out of step with everything going on around them in New York, and the spotlight had been dragged to the opposite coast, where a similarly inclined band named Van Halen were rapidly making a name for themselves.

Narita – named after the main international airport in Tokyo and featuring their man-seal mascot Tior dressed as a sumo wrestler on the cover – was released in June 1979, but initially only in Japan. Once again, America wanted nothing to do with Riot.

By the time of their second album, Riot had already gone through several of the line-up changes that would define their career. Original bassist Phil Feit had been replaced by Jimmy Iommi during sessions for the debut album, while second guitarist LA Kouvaris had quit shortly afterwards, with Rick Ventura filling his shoes.

“It was Mark’s band,” says Ventura. “He started it. Sometimes, we had some conflicts because he wanted the band to be a certain way.”

Now, between finishing Narita and releasing it, they’d got a new drummer, New Jersey native Sandy Slavin.

“I’d never heard of Riot,” admits Slavin today. “Mark called me and said his band had just got rid of their rhythm section. I thought, ‘These guys are idiots – they’ve got a record out. Why the fuck did you break up your band?!’ But Mark seemed real nice. We we were both big fans of Montrose.”

But there were bigger problems than a revolving-door membership. Riot were struggling to get a break in their home country, and Arnell and Loeb realised they needed help to give their charges a leg-up. They opted to go into partnership with Fred Heller, a powerful music-business figure who had represented Ian Hunter and Lou Reed.

“Fred made a huge difference because he could get on the phone with label executives,” explains Arnell. “Freddie knew how to make people dance.” Heller made his presence felt immediately, bagging a deal with Capitol Records for the US release of Narita and wrangling a tour supporting AC/DC in Texas. After three years of having the door slammed in their faces, Riot figured that they were on the verge of stepping into the big time.

"They were the first arena shows any of us had done,” recalls Slavin. “We were like, ‘Yeah, we’re rock stars now!’ Billy and Steve were like, ‘What colour Mercedes do you want?’ We acted like idiots and busted up some hotel rooms. We went from a zero to a thousand.”

The reality was that Riot were still struggling to make their mark – a situation which led to some drastic brainstorming on the part of Arnell and Loeb. In late 1979, they called a meeting with the band. Slavin: “They said, ‘There’s no market for hard rock – you need to change your whole sound, get skinny ties and go New Wave.’ We were young and full of piss and vinegar. We said, ‘Fuck this crap!’”

The prospect of a potentially disastrous career change averted, Riot found their luck temporarily changing. Thanks to the support of taste-making British DJ Neal Kay, the band had gained a sizeable following in the UK, and in February 1980 they were offered a slot supporting Sammy Hagar on his British tour.

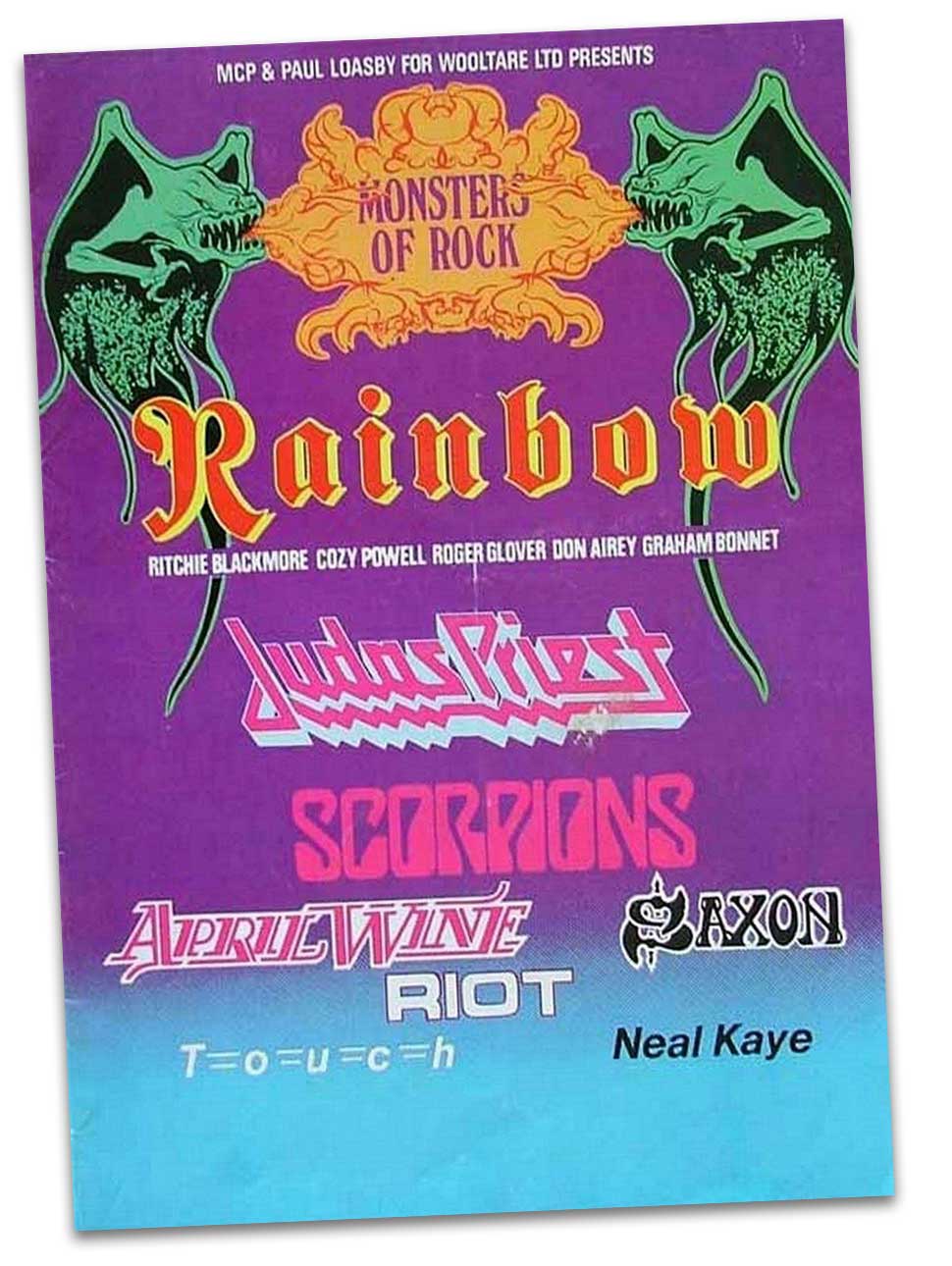

It was such a success that a few months later they were back, having bagged a spot at the inaugural Monsters Of Rock festival at Donington, though not before yet another line-up change, with bassist Kip Leming joining on bass.

“It rained and there was mud everywhere,” recalls Leming with a laugh. ”I went out into the audience to check out the band and got pelted by lumps of turf.”

Riot returned home in triumphant mood. They started worked on their third album, Fire Down Under, with the wind in their sails. Little did they know that the ship was about to be holed below the water line.

Looking back on Fire Down Under today, guitarist Rick Ventura recalls a band putting their struggles behind them.

“It was one of those moments,” he says, “where the chemistry was right, the attitude was good and everyone was playing great. It all came together.”

Mark Reale and Guy Speranza wrote together, with Ventura bringing in fully assembled songs of his own. Everybody chipped in with arrangements. After half a decade of turmoil, the band were finally pulling in the same direction.

“We had reached the point where the band was tight,” says Billy Arnell. “They’d started to get an artistic identity. As producers, Steve and I couldn’t really fuck it up.”

Fire Down Under stands as the high point of Riot’s career, and a landmark early-1980s hard rock record. Bridging the gap between Reale’s beloved Montrose and the nascent thrash scene that would emerge a few years later, it balanced its melodic chops with a tight energy and walked a lyrical tightrope between fantasy and gonzo rock’n’roll.

Its undoubted highlight was anthemic opener Swords And Tequila, a song that has been rightly fêted as a classic by Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris and Metallica’s Lars Ulrich. Surprisingly, it also influenced another more unlikely musician.

“Listen to the beginning of Swords And Tequila, then listen to Lady Gaga’s track Electric Chapel,” says Sandy Slavin. “The guitar intro on that is so fucking close it’s unbelievable. Not just the notes, but also the sound. She’s really into 80s rock, right?”

After two false starts, Riot had at last made their masterpiece – the album that would book their place at rock’s top table. At least that’s what should have happened. Instead, Capitol refused to release it.

The official line was that the label deemed it ‘commercially unacceptable’ – too heavy for the climate of 1981. But Slavin suggests that the real reason was down to a failed power-play by Billy Arnell and Steve Loeb.

“There was a song by Rick called You’re All I Needed Tonight that our A&R guy liked,” says Slavin. “He said it was a big hit, and he took a tape to the executives in LA and played to them. Then Billy and Steve don’t put the song on the album – it was their way to put the A&R guy in his place. Of course, the A&R looks like an idiot. That’s when the label decided that it was ‘commercially unacceptable’.”

Whatever the reason, the knockback was disastrous for Riot. Arnell decided to go toe-to-toe with the label and get the fanbase involved. He sent out a postcard to all the fans on their mailing list, invoking their axe-wielding, seal-headed mascot: “Tior is held captive in the ivory tower by the maniacal company executives.”

He worked up a petition to get the album released, signed by fans and such high-profile supporters as Iron Maiden. The cause was picked up by the British music press, if not their American counterparts.

Rather than having the desired effect, the campaign only made things worse. Not only did Capitol refuse to release the album, they weren’t inclined to let Riot go. While things hung in limbo, Riot’s funds dried up. Cracks were growing between the co-managers and the members of the band who weren’t Mark Reale and Guy Speranza.

“The band’s money was cut off,” says Slavin, still fuming at the memory. ”I had to give up my apartment in New York, move back to New Jersey. It was fucked. Billy and Steve had kept the money [from the deal with Capitol], so they could have kept us going. Then they sold it to Elektra. They sold the fucking record [Fire Down Under] twice.”

The band’s money was cut off. I had to give up my apartment in New York, move back to New Jersey. It was fucked."

Sandy Slavin

It was Elektra Records, fired up by the enthusiasm of hotshot A&R man Tom Zutaut, who proved to be Riot’s saviours. The new label helped extricate Riot from their Capitol deal, and finally released Fire Down Under. To the relief of the band, it was a success, selling more than its two predecessors combined (it would eventually sell more than 500,000 copies in the US).

Yet Riot’s capacity for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory was unmatched, and once again their world was about to come crashing down around them. In November 1981, while supporting Grand Funk Railroad, Guy Speranza – whose nickname was Buddy – dropped a bombshell.

“Guy turns to me and Mark and starts talking in the third person,” recalls Slavin. “He says, ‘Hey you guys, Buddy’s packing it in.’ We thought he was joking, so we didn’t say anything. Then we get back to the hotel and he says, ‘I’m really quitting.’ He announces that he’s getting married and his wife-to-be doesn’t like rock’n’roll.”

In a career defined by terrible timing, this was the worst timing of all. The band had finally made their breakthrough, and now their frontman was walking away from it for love.

Today, everyone has a different take on Speranza’s departure. Bassist Kip Leming suggests that the singer was unhappy with the idea of “putting on the leather pants and sparkly clothes – it wasn’t about music”. Sandy Slavin says that the singer was “fed up with Billy Arnell and Steve Loeb – he was tired of touring and not getting any reimbursement.”

Unsurprisingly, Arnell himself has a different take on the matter. “Guy was a very mellow, gentle person,” he says. “For a frontman, he wasn’t very confident. He was a great writer, and he was very identifiable, but it takes more than that.”

Whatever the reason, Speranza had made up his mind. He played his last show with Riot on December 22, 1981, the second of two sold-out shows supporting Rush at the Meadowlands Center, Rutherford, New Jersey.

“I have a picture of Guy from that show,” says Sandy. “He has his coat over his shoulder, he’s walking out of the dressing room, and that’s the last time I ever saw or talked to him. He was just glad to be gone.”

Speranza left the music business and became, of all things, a pest controller. One apocryphal story has Lars Ulrich, a Riot fan, calling a pest control company to sort out an infestation of rats in his New York apartment; he was shocked when it was Guy Speranza who knocked on the door.

Years of struggle culminating with the loss of a key member would have been a fatal body-blow for most bands. But for Mark Reale, there was no question of stopping after all his band had been through.

Riot returned to New York, bloodied but not broken. They held a few low-key auditions and quickly found a replacement for Speranza in the shape of Rhett Forrester. A bandleader’s son from New Jersey, Forrester had chiselled features, blonde hair and a cocky style developed in an assortment of cover bands.

With their new singer on board, the band entered the studio to record their fourth album, Restless Breed, a tougher, more metal-centric record that predated Quiet Riot’s sonically similar though much more successful Metal Health by almost a year.

“Not having Guy there was bad enough,” says Slavin. “But with Rhett, it was always about putting on a show. It didn’t feel genuine.”

It soon became apparent that Forrester was a volatile and insecure character. He became prone to picking fights. Worse, he was unreliable, as the band found out on their first tour with him.

“We got to Nashville, and we hear that Rhett’s going to make a later plane, which is always a bad sign,” recalls Slavin. “Suddenly, there’s a call for our tour manager. He comes back and says, ‘Fellas, the tour is over – Rhett’s in the hospital.’” It transpired that Forrester had attended a Queen show at Madison Square Garden, and ingested something at the aftershow that saw him hospitalised for four days.

Forrester got his act together enough to make another album, the underwhelming Born In America. But the band were losing their way, and so were their managers. Producing the album, Steve Loeb would go into the studio during the day and Billy Arnell at night, the latter accompanied by two bodyguards for protection.

By this time, Arnell had had enough. He quit the management team, cutting his losses. Today, he makes a successful living in the computer industry, while writing and producing music on the side. Now flying solo, Loeb tried to take Born In America to other labels following a dispute with Elektra, but no one was interested.

“And then Steve had the balls to turn up at Elektra with the album as if nothing had happened,” says Slavin. “They called security and threw him out of the office.”

Rick Ventura, who found it hard to disguise his lack of enthusiasm, was pushed out of the band. They embarked on one more tour, supporting Kiss, before deciding to call it a day. Their swansong show was at L’Amours club in Queens, in May 1984. “That was a show I put together,” says Slavin wryly. “We made more money on that date than we did on the whole Kiss tour."

Even if what passed as their glory days were over, Riot itself weren’t. Mark Reale relocated to San Antonio and briefly formed a new band, Narita (named after Riot’s second album), before resurrecting his old band’s moniker.

He would record another 10 albums with a series of different Riot line-ups, though none came close to Fire Down Under (and one of which, the horn-driven Privilege Of Power, was an unmitigated, experimental disaster).

Riot’s run of bad luck didn’t stop with their initial split. On January 2, 1994, Rhett Forrester was shot and killed during a car-jacking in Atlanta.

“The police guess he was reaching for something in the glovebox and whoever was standing outside the car, probably selling him something, thought he was going for a gun and shot him in the back,” says Sandy Slavin. “Rhett then drives the car away and crashes it into a police car. That’s Rhett!”

On November 8, 2003, Guy Speranza passed away after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. In an interview, Mark Reale revealed that his wife believed this was related to the chemicals he handled every day for 20 years in his job as a pest controller.

Then, on January 25, 2012, Mark Reale died of complications from Crohn’s Disease, the crippling stomach ailment that he had been battling for most of his life. He was still flying the Riot flag, until his illness got too bad for him to continue. A week before Reale died, Rick Ventura turned up to jam with the current Riot line-up in New York.

“I planned on going down and surprising Mark,” he says, “but he was too sick to play. I miss Mark, and I miss Guy too.”

It’s a stretch to say that Riot were cursed, but they seemingly spent their career caught in a perfect storm of misfortune, apathy and bad timing. But while theirs was a career template not to follow, they made a lot of mistakes so that other bands didn’t have to. It’s to their credit – and especially to Mark Reale’s credit – that they persevered in the face of it all.

Thirty-one years after their masterpiece, Fire Down Under, the surviving parties have bittersweet memories of Riot. “The thing I remember about Riot is the laughing,” says Sandy Slavin. “We always had a lot of fun.”

“The band has its place in history and it seems we’ve influenced a lot of people,” says Rick Ventura. “I’m really proud of that.”

“I guess for a time,” adds Kip Leming, “we were the biggest small band in the world.”

Riot V, who formed in 2013, continue to fly the Riot flag and have released two albums: 2014's Unleash the Fire and 2018's Armor of Light. This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 174.

Pete Makowski joined Sounds music weekly aged 15 as a messenger boy, and was soon reviewing albums and doing interviews with his favourite bands. He also wrote for Kerrang!, Soundcheck, Metal Hammer and This Is Rock, and was a press officer for Black Sabbath, Hawkwind, Motörhead, the New York Dolls and more. Sounds Editor Geoff Barton introduced Makowski to photographer Ross Halfin with the words, “You’ll be bad for each other,” creating a partnership that spanned three decades. Halfin and Makowski worked on dozens of articles for Classic Rock in the 00-10s, bringing back stories that crackled with humour and insight. Pete died in November 2021.