“The bar owners pulled guns on us. It was over whisky and disrespect. We were 22 and hard as steel”: The incredible story of the forgotten Detroit hellraisers who blazed a trail for Alice Cooper, Bob Seger and The Stooges

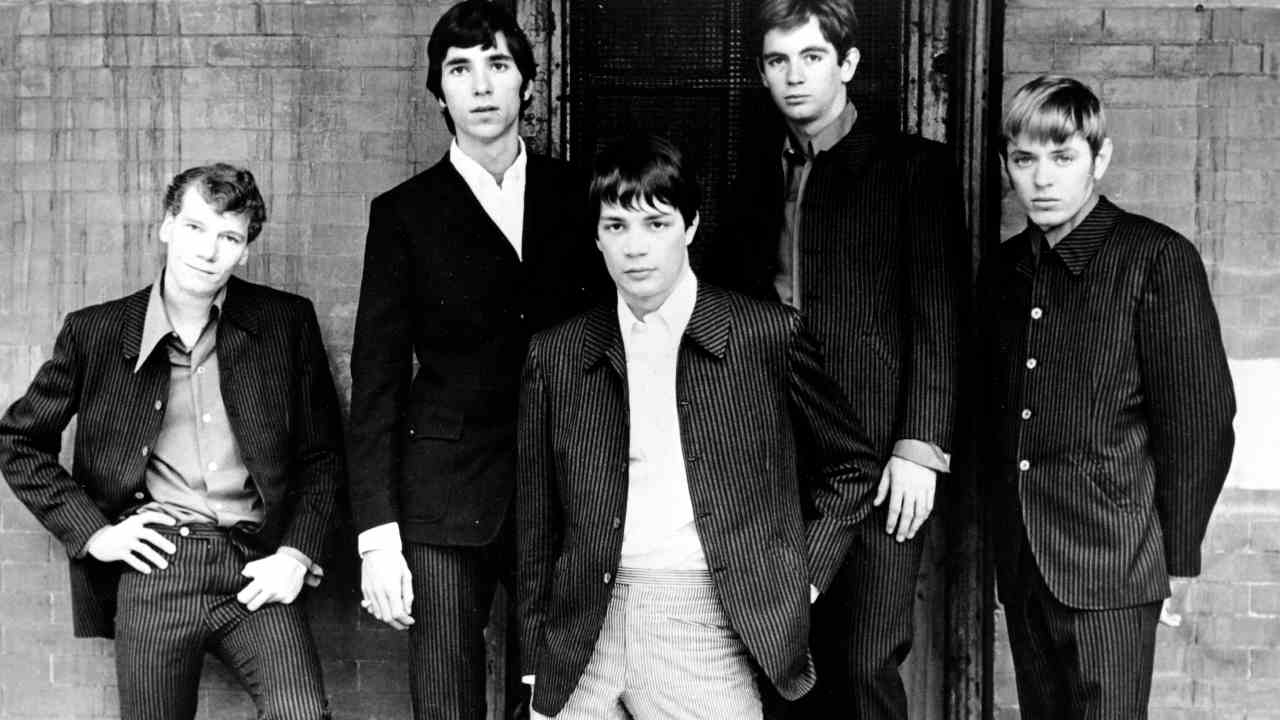

Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels are one of the great lost American bands of the 60s

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

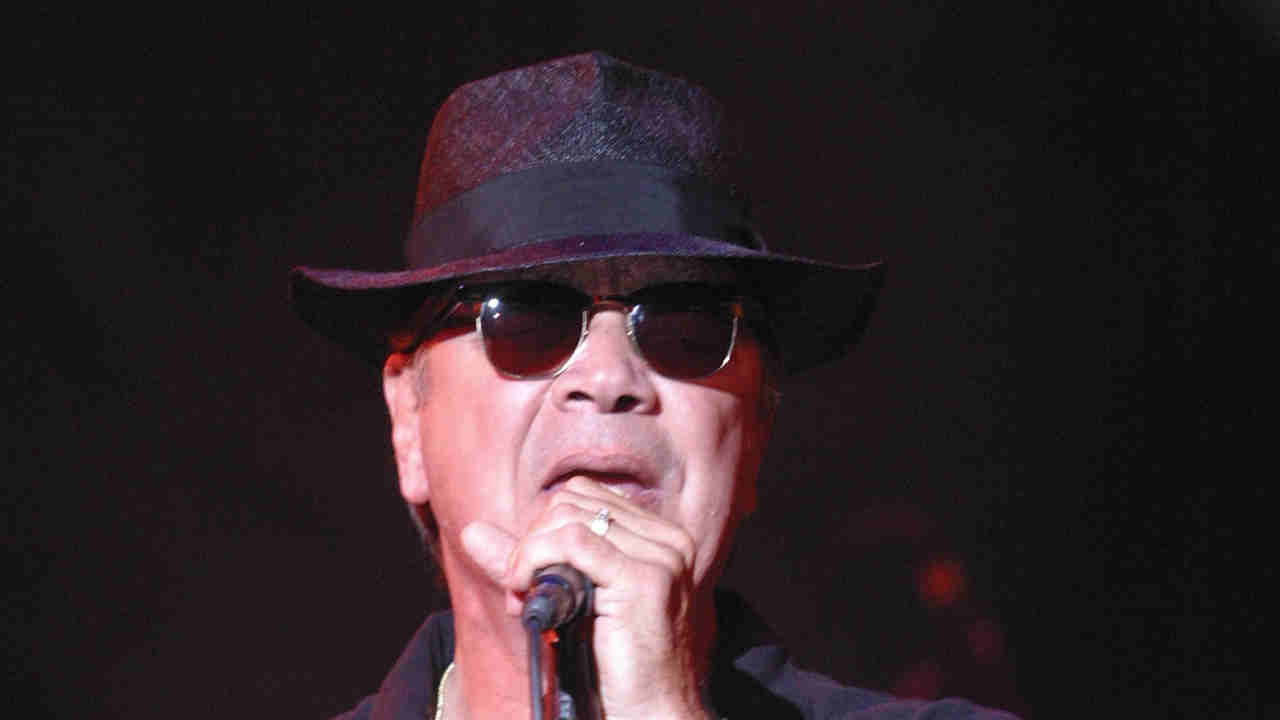

Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels were one of the great forgotten garage rock bands of the late 60s, In 2008, Ryder and his former bandmates looked back over the career of a band who should have been as big as Alice Cooper or Bob Seger.

The Detroit of the late 60s and early 70s was a musically vibrant city, with diversity in abundance. Motor City was booming, and the likes of Bob Seger, Alice Cooper, The Stooges, MC5, Ted Nugent’s Amboy Dukes and Grand Funk Railroad were all receiving national acclaim, albeit in varying degrees. Riding high on the crest of this musical wave were Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels.

Ryder was born William Levise Jr in 1945 in Hamtramck, a suburb of Detroit known for its high population of Polish immigrants. At school he discovered a love for black R&B. Keen to explore that side of his vocal range, he joined a band called Tempest. Soon after he joined The Peps, a quartet made up primarily of black singers. Then his music career was interrupted when he left Detroit for LA.

On his return he formed a band called Billy Lee And The Rivieras, comprised of bassist Earl Elliot, lead guitarist Jim McCarty, drummer Johnny ‘Bee’ Badanjek and rhythm guitarist Joe Kubert, whom Levise had played with in Tempest. At the request of producer Bob Crewe, the group changed their name to the Detroit Wheels. Levise chose the name Mitch Ryder by flicking through a phone directory, and has used it ever since.

“I cut a record on a gospel label in Detroit when I was 16, and I started frequenting a club called The Village downtown,” he says. “Basically, it was black urban musicians that performed there. I got involved singing with a black group there and I became a regular at The Village.

“Every once in a while they’d have auditions for new house bands coming through, I think essentially because the owners didn’t want to pay an established band. They would say that they were auditioning for a house band, and the auditions you’d have to do for free. One weekend these three guys came through – Earl Elliot, Jimmy McCarty and Johnny Badanjek. Their mission was to back up all of the artists on the show, me being one of them.

“We did the performance, and talked about getting together at some point in the future, but we let it go. Then I went down with a good friend of mine from high school, Joe Kubert, who later became the rhythm player, and we were listening to the madness that surrounded The Beatles going on in America. We said to ourselves: ‘This is a piece of shit. We can do that.’

“We drove to Detroit and started to put a band together. And I remembered the guys that I’d met at The Village. We called them and arranged some rehearsal, pulled Joey in on rhythm and did some rehearsals. That’s how it began.”

Drummer Johnny Bee takes up the story: “The Beatles had just come out, and [Ryder] wanted to have a band like that. We said that we’d get together at my house and try it out, see what happens. Billy [Ryder] brought over a guitar player named Joe Kubert, and that was the start.”

From there the band would rise rapidly, signing to the New Voice label. The Wheels had five songs in the US Top 40 between 1967 and ’68, including classics like Sock It To Me Baby and Devil With A Blue Dress On. The band recorded three albums in those years – 1966’s Take A Ride, Breakout from the same year and 1967’s Sock It To Me. While the first two contained a lot of cover versions, the last album was made up almost entirely of original compositions and is widely considered their best record.

“We started playing all the TV shows,” says Johnny Bee. “Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, The Jerry Bevat Show… there were many more. And we started playing with all the big groups – the Dave Clark Five, Simon And Garfunkel, The Byrds, the Beach Boys [Beach Boys hub Brian Wilson once said in a Rolling Stone interview that he thought Mitch Ryder was the greatest singer in the USA].

“This stayed pretty even for about two years, until Crewe decided that Mitch should become the white James Brown. Then the train was about to come off the tracks,” says Bee.

In 1967, disillusioned by the music business, Ryder broke up the Detroit Wheels in order to go solo. “There were differences between me and Jimmy,” Ryder says. “We were both very strong personalities. That alone couldn’t have broken the group up, but I used to room with him and we’d argue constantly. We always came down to the fact that most of my heroes were black, urban R&B artists, and that was the direction I wanted to go in. Jimmy could play good rhythm and blues because he had grown up in Detroit, but he wanted to go more into a rock’n’roll vein. I wanted to make the band bigger, and he wanted to keep it small.

It was a bunch of some of the hardest-living guys. The drug intake wasn’t even human.”

Mitch Ryder

“That existed between us along with the agenda of the producer. There came a time and place where the producer made the split happen. We were miffed because we couldn’t do our own material, as we always had done. It was my goal to become a rhythm and blues singer, at a time when the country was about to shit on rhythm and blues. They wouldn’t care about it any more. Then there was flower power and the Brit invasion, which I adore.”

Before long, though, Ryder and Johnny Bee were back together, this time simply called Detroit. “There was a period of a couple of years where there was an attempt to re-form the Detroit Wheels, which was ill-fated, and that morphed itself into the band Detroit,” Ryder says. “That was under the tutelage of Barry Kramer, who published Creem magazine. Barry was my manager as well.

“Johnny [Bee] was in the Detroit band. That group was doomed for destruction. It was a bunch of some of the hardest-living guys. The drug intake wasn’t even human. The level of anger and violence, too. The beauty of it was that it was able to be channelled into the music. When you listen to the limited amount of music that was created by that group, you understand that the weird, powerful energy is coming from a place of anger and violence. Although it’s scary, it’s still incredible to listen to. I could handle one dose of that. I was only good for one album then I walked.”

Also in Detroit was bassist Ron Cooke from the Catfish Blues Band. “I was running with that crowd of musicians anyway,” he recalls. “The position became open and they were back in town. They called up and said: ‘Hey, come on down and jam for a bit.” That’s when we were in the Creem building. I went down one afternoon in the summer, and it was so hot up in there. We got to jamming, and the next thing I know, they called and said: ‘The car’s leaving town. Be there.’ We jumped in the limo and hit the road.

“One of the guitar players in the Detroit band was Mark Manko from the Catfish Blues Band, too. We called Harry Phillips up, the keyboard cat, he played with the Catfish Blues Band, and he came out and we had the band together. It was a rolling circus after that. Johnny Bee had always been Mitch’s drummer. The Wheels had split up maybe four years before that, and I joined the Detroit band around 1969. I guess that Billy [Mitch] and Johnny were the driving force of putting that together. It was time for the Bee and Mitch to reunite.

“The Detroit band was actually in a gunfight in a bar, two doors from Fenway Park in downtown Boston,” Cooke continues. “That was one wild-ass rock’n’roll band right there, man. The bar owners pulled guns on us. We pissed them off, told ’em to fuck off, give us more whisky. It was over whisky and disrespect, and we told ’em, ‘Fuck you. We’re not kissing your ass, how d’ya like that?’ We were 22 and hard as fucking steel.”

“The band had incurred such debt from touring and different situations that we couldn’t even pay off the debt with the contract.”

Ron Cooke

Just like the Detroit Wheels, though, Detroit soon disintegrated under a great cloud of confusion and, ultimately, disappointment following the release of just one album.

“We were gonna sign with Atlantic Records,” says Cooke. “I guess we had one of the biggest deals at that time. It was a huge amount of money. The band had incurred such debt from touring and different situations that when we got to the point where it was time to sign the contract we couldn’t even pay off the debt with the contract. At that point in time we would’ve been working for nothing.

“Everybody was so worn out. There was some talk of trying to go on [after Ryder left], but then we said to hell with it. Everybody just went their own way. It was eight months to a year before anybody started working again. It was like being adrift in a sea of shit.”

Following the disintegration of the Detroit band, Mitch Ryder worked under his own name. Johnny Bee played with artists as prestigious as The Rockets and Alice Cooper (on his Welcome To My Nightmare album) and the Howling Diablos. Jim McCarty went on to work with Cactus. Ron Cooke later worked with former MC5 man Fred Smith’s Sonic’s Rendezvous Band, and later still with Wayne Kramer (MC5) and New York Dolls/Heartbreakers man Johnny Thunders in Gang War. In 2008, Cooke got together with Johnny Bee to record a new Detroit album, although Ryder was notable by his absence.

The names Mitch Ryder, the Detroit Wheels and the Detroit band are permanently etched into rock’n’roll history, and but it’s hard not to wonder what might have been if this group of musicians had been better managed. It’s not uncommon in rock’n’roll for this much promise to go up in smoke. But such is the quality of the music that these guys made together, the story of Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels must go down as one of rock’s great missed chances.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock issue 116 (March 2008)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.