"Wildflowers scared him, because he's not really sure why it's as good as it is": As Tom Petty’s world fell apart, he took refuge in the studio and made his most deeply personal album

The story of Tom Petty's classic Wildflowers, an album full of sadness, humour and hope

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Tom Petty thought he was just making another solo album. Instead he ended up performing open-heart surgery on himself, without anaesthesia, and recording the whole procedure. Wildflowers, the 1994 album he believed was his best work, has since become the Rosetta Stone of his career: part confession, part escape hatch, part love letter to the wreckage of his life. He cracked himself open, not to shock, but because he couldn’t hold it in any more.

Between the summer of ’92 and spring ’94, while Petty recorded Wildflowers his 22-year marriage to Jane Benyo was in collapse; he fired Stan Lynch, the only drummer the Heartbreakers had ever known; and he severed ties with MCA, the record company that had shepherded him through a dozen years of hits (and mutual lawsuits). He even shifted course from using Jeff Lynne, the producer who had brought him Grammys, Wilburys and a second act.

“He was blowing up every aspect of his life,” says Mary Wharton, director of the documentary Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making Of Wildflowers. “From his personal life to his business life to his creative life, Tom was trying to figure out how to put things back together in a way that made sense to him in that moment.”

During the early stages of the pandemic, three years after Petty’s death, Wharton was contacted by her fellow VH1 alum Adria Petty, to fashion a film from unearthed 16mm reels of studio footage shot during the recording of Wildflowers. Petty’s daughter had found the never-before-seen footage in her father’s archives. It captured some of the most vulnerable moments of the artist piecing together the most personal record of his career.

While delighted to be reunited with Adria, the award-winning filmmaker found something unexpected in the footage: not a flinty superstar, sanguine and cool while plotting hits, but a man stripping himself raw.

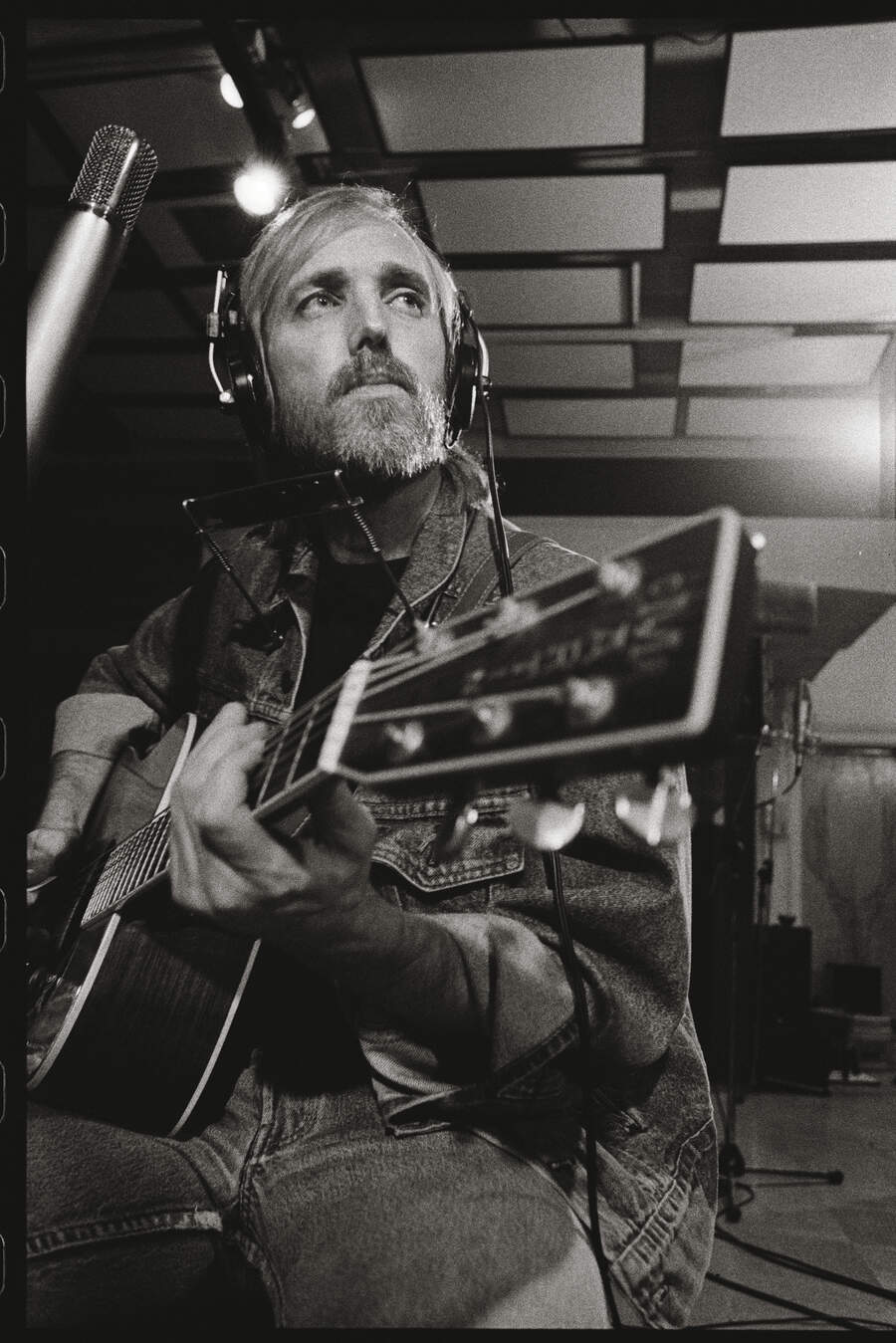

“This is Tom at his most honest, most vulnerable,” she explains. “He wasn’t trying to make a hit, he was trying to make sense of his life. You see the joy in the work. He looks lighter in those moments. Like the music was carrying him someplace else.”

That “someplace else” announced itself on a warm spring day in 1992 as Tom Petty drove home from the upscale resort town of Santa Barbara. The road glittered like a mirage, sunlight slicing across windshield like an acid flashlight, the coastal hills were covered in a seamless patchwork of golden California poppies and purple lupine.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Something about that distracting riot of colors, light and the somnolent hum of traffic lodged in Tom Petty’s psyche as he drove back to his Encino home – only to emerge months later when he turned on his eight-track tape recorder.

Wildflowers was not the first song written for the album. It appeared full-blown in 1993, a year after he began writing songs for what would become his second solo album. Petty was always amazed by the miraculous nature of the process, likening it to when Bob Dylan wrote Like A Rolling Stone, which Dylan claimed began as “a long piece of vomit”. Explaining to Paul Zollo for his 2005 book Conversations With Tom Petty, he said: “I swear to God, it’s an absolute ad-lib from the word go. I turned on my tape recorder deck, picked up my acoustic guitar, took a breath, and played that from start to finish.”

While the California landscape outside looked pastoral, the one inside Petty’s head was closer to a demolition zone. His marriage to Benyo, whom he’d known since high school and was the mother of his two daughters, was disintegrating. The Heartbreakers were in flux: Lynch sulking since Petty’s first solo album, Full Moon Fever, Benmont Tench and Howie Epstein grumbling that playing Petty’s solo songs made them feel like a covers band.

Petty had already decided Lynch wouldn’t play on the new record. His longtime label, MCA, was another relationship headed for divorce; he’d already stashed a Warner Bros contract in a vault, waiting to satisfy MCA with a ‘greatest hits’ package. It was midlife crisis as controlled burn, with family, band and business all ablaze at once.

And yet, instead of resorting to rock’n’roll flamethrowers, Petty turned his gaze inward. Always a master of brevity, sly humor and a winking kind of Southern bravado, he came across as uncharacteristically wistful, introspective, and far more personally forthcoming than at almost any other time in song.

Unpretentious, straightforward and emotionally naked, he betrayed no hints of his usual blithe stoicism and insider’s nonchalance. Why? Because never before had he been at this particular crossroad, one that demanded action.

The sparse, unadorned title track begins with deceptively lighthearted acoustic guitar, spinning an escapist dream from the ruins of his marriage, a plea not to repeat the abusive cycles of his childhood. ‘You belong somewhere you feel free,’ he sings. His therapist confirmed the self-diagnosis, according to his daughter. “That song is about you. That’s you singing about what you needed to hear.”

Producer Rick Rubin knew how to frame this new voice. “Whatever the thing in front of you, make it the best version of what it is,” Rubin told Rick Beato in 2024. “That goes to [Petty’s] vocal. We put it up front. [So close] sometimes you could hear him breathing. We weren’t looking for perfection, but looking for reality and getting closer to who he is. Where you feel he is singing to you. I’m hearing the human behind the words.”

Wharton’s film reinforces it, showing the Ugg-boot-wearing Petty staring directly into the camera, with his pale blue eyes confessing: “I feel much more comfortable being myself. I feel more like me.”

Truly the people’s rock star, Petty had always made music for the tribe, for outsiders like himself. But for the first time, he wasn’t writing to empower fans or to rally an audience. He was writing for himself.

“To me, the idea of going on with it and continuing to try to do your best work, it’s a natural thing to keep myself interested,” he admitted. “If I think it’s not going to be great, I don’t want to do it. And if something is coming out like something you’ve done a million times, I know enough to walk away, let’s go on to something else.”

The Heartbreakers weren’t ready for “something else.” But did they even have a choice? Wildflowers was going to be a solo album. Stan Lynch, an original Heartbreaker, had never forgiven Petty for making his first solo album, Full Moon Fever, without him – the only Heartbreaker not to appear on the record. Lynch called the songs weak, and made noises about Petty plotting to go solo and drag guitarist and songwriting partner Mike Campbell along.

“The Waiting always reminds me of Stan,” Petty said later. “He’s the only drummer in the world who could play it. Nobody could play that song but him.” But by 1992 Petty had had enough. He quietly polled the band about firing Lynch, and no one told him not to. “For him to leave was a major change,” Petty admitted. “So Wildflowers is kind of Mark Two Heartbreakers.”

Even his record label felt like dead weight. Petty’s relationship with MCA had been rocky from the start: lawsuits, bankruptcies, fights over pricing and creative control. He knew he had to get out. At a dinner with Warner Bros. chairman Mo Ostin, he was told: “I’d sign you on the spot.” Petty covertly inked the deal, and hid the contract until MCA’s obligations were satisfied with 1993’s Greatest Hits.

That left Jeff Lynne, his friend, Wilbury brother and producer of both Full Moon Fever and the Heartbreakers collaboration Into The Great Wide Open. Petty admired, respected and genuinely liked Lynne but feared stagnation. “We were making a certain kind of record,” he told Rolling Stone. “If we did any more, it wasn’t a great idea. I felt I have to take off on my own, see what all this adds up to.”

The records had gone platinum, the songs had filled stadiums. But Petty was restless. He wanted risk. He wanted to hear what Tom Petty sounded like without frills.

Enter Rick Rubin, barefoot Zen archer of hip-hop and metal. Rubin hadn’t grown up a Petty fan. “I usually liked much harder stuff,” he admitted in Wharton’s film. But Full Moon Fever cracked him open. “I listened to Runnin’ Down A Dream all day every day in my car for a year.” By chance – or fate – Rubin and Petty crossed paths on a Warner Bros jet in 1992.

According to Adria Petty, who was on that flight, her father was initially skeptical about the producer. In a 2020 interview on the Broken Record podcast, she recalled Tom’s first impression: “My dad comes back and he’s like: ‘He’s not a corporate man. He looks like a homeless guy, and he is wearing no shoes.”

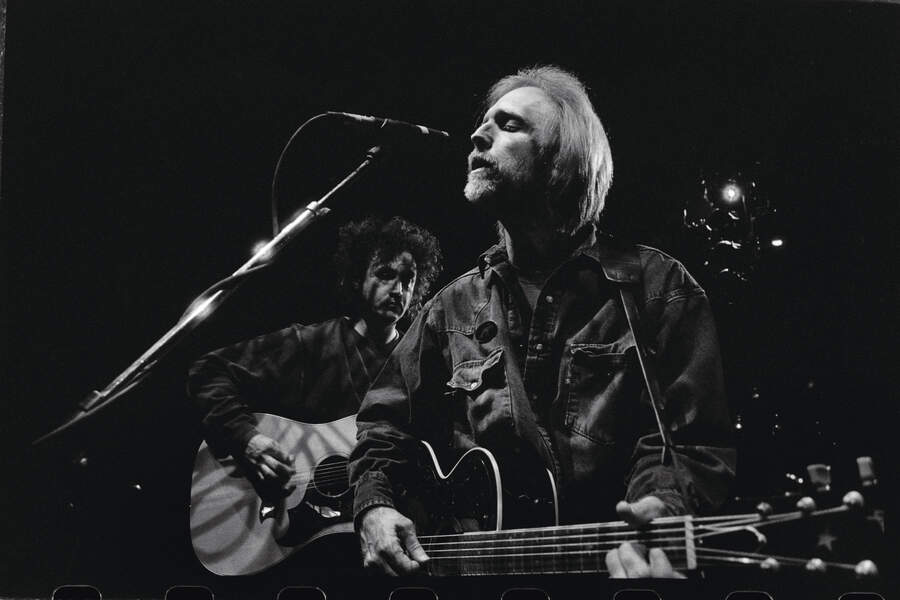

But during the flight he seemed to thaw a little when he noticed Rubin was listening to Neil Young albums. Somewhere over Ohio, a conversation about Bob Dylan – they had both attended a Dylan tribute concert – sparked Petty’s interest. By the time the plane landed in Los Angeles, they’d agreed to try something together.

Their sessions began casually at Petty’s Encino home. Rubin would come over and Tom would play three or four songs. This went on for two years. By the end, Petty had written close to 70 songs, 30 of which would make up the Wildflowers sessions. It was the most prolific period of his life, and also the most mystifying.

“I can’t really figure out how that keeps happening,” Petty told me later. “They just keep appearing. I swear I feel like it’s never going to happen again. If someone said: ‘You have to write an album in six months’, I’d think: ‘Oh god, I can’t do it.’ Somehow it happens again.”

He hated the idea of dissecting songwriting. “I’ve always been annoyed when I see songwriters on television elaborating about what they wrote,” he said. “It has never been like that for me. I’ve never sat down and gone: ‘I’m gonna write a song about this’, and then did it. I just sit down and start to play, and the next thing I know it’s somehow there. You’re damn lucky to get one. Getting a good one is so hard.”

That’s why what happened with the song Wildflowers boggled his mind. It gave him a sense that he might really have a pipeline to the divine. Or as he used to glibly say: “Every song has already been written, you just have to tune yourself in to the cosmic radio station.” But it’s not clear that he really believed that. Until it happened to him.

But that day in his home studio, it did. Wildflowers descended whole, like a transmission he was picking up on a private frequency. Crawling Back To You and It’s Good To Be King felt less like compositions, more like confessions. Even You Don’t Know How It Feels, which became the unlikely hit, sounded like a shrug more than an anthem: the line ‘Let me get to the point, let’s roll another joint’ got the song banned on MTV and VH1, forcing him to alter the lyrics.

For a man who had defined himself by anthems – Refugee, I Won’t Back Down, American Girl – this shift was seismic. “I’m real bored with anthemic,” he said flatly. “I did it. I’m not trying to do it again. Younger people should do that. I wanted something quieter.”

Quieter but not smaller. These songs whispered directly into your ear. Instead of shouting at the rafters, they exhaled. Petty was startled by what he heard on playback. Could he have made this album 10 years ago? It was a long journey to self, but rewarding once you rrived.

“It’s more fun to be yourself all the time,” he explained. “I’m not saying I’m the perfect person, because I’m not at all. But I am right up front all the time. Which is hard for people. It’s hard for my family sometimes.” The family he couldn’t save – Jane, his daughters, the unravelling home – haunted the record in not-so-difficult-to-break coded form. The studio was the one place where he could control the chaos.

“There was definitely tension in his life,” Rick Rubin told Warren Zanes for the latter’s 2015 book Petty: The Biography. “[It]seemed he didn’t really want to leave the studio. Like he didn’t want to do anything else in his life. I think he wanted to take his mind off whatever was going on at home.”

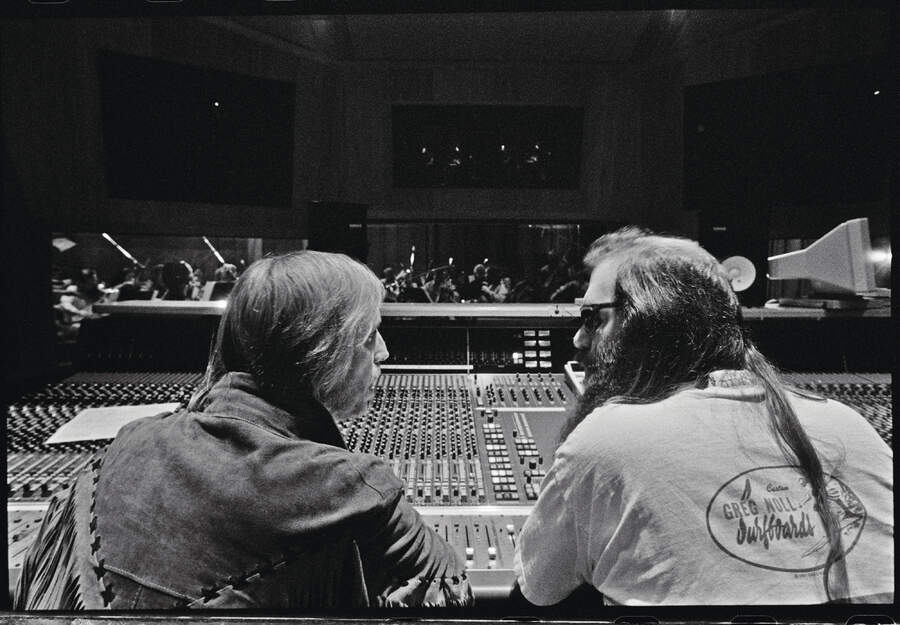

By the time Petty settled into Sound City then Mike Campbell’s home studio with Rubin, the sessions became less about recording tracks and more about building a shelter. While life outside the studio was collapsing, life inside it was strangely simple: play, listen, write, repeat.

Petty didn’t hide that truth. “Being on stage is a pretty comfortable place,” he once admitted. “Life is much more complicated than a rock’n’roll set.”

In the studio he could orchestrate every detail – the hush of an acoustic guitar, the whine of a harmonica, the subtle lift of Steve Ferrone’s hi-hat. The chaos of marriage and family couldn’t be tuned or equalised, but in the studio he could make sense of it all.

And he never stopped. Rubin described how Petty would call him over just to play a handful of new songs, casually dropping confessions on tape as though he were keeping a journal.

The truth is, Wildflowers was meant to be a double album. Petty had the material, Rubin supported the vision, and the band were behind it. Warner Bros, however, had reservations. A sprawling, 25-track confessional wasn’t exactly how they wanted to launch Petty’s new era with the label. So the guillotine came down. Ten songs were axed. Four of them – California, Hope You Never, Hung Up And Overdue and Climb That Hill – were instead included in the 1996 Jennifer Aniston film She’s The One. Rod Stewart took Leave Virginia Alone, and the rest were hidden in vaults, safes and bedroom closets.

Sequences were reordered, then reordered again. “That took us about three months,” Petty kids in Wharton’s film. But you get the idea he was telling the truth.

Some say Petty didn’t fight as hard as he might have for a double album. But given how conscious he was of the price of music for his fans, a double CD would have been cost-prohibitive.

Yet even reduced to 15 tracks the record felt infinite, a universe unto itself. Petty still wanted to release the ones that didn’t make the cut, which he felt were not inferior in any way. The discarded songs would emerge decades later on the Wildflowers & All the Rest package, confirming what insiders had known all along: Petty wasn’t exaggerating when he said this was his most fertile, most mystical period.

As in awe as he was of his beneficent muse, he was reportedly equally terrified by it. Adria Petty doesn’t believe it: “I never heard him say that!” But Rick Rubin claimed he was haunted by the album. “Wildflowers scared him, because he’s not really sure why it’s as good as it is,” Rubin explains in Wharton’s documentary. “He felt he couldn’t make Wildflowers 2,” the producer added.

It had never happened to him before. He didn’t know what had thrown open the floodgates that allowed songs to just appear.

“I can write a song very easily, but it won’t necessarily be any good,” he explained in 2006. “There’s a bit of craft involved; I don’t like to rely on that. I have got to wait for the ones that are really good. Often during an album, I write six really bad ones and then I write a good one. Randy Newman says that if you sit there four hours, something will happen.”

If the album frightened Petty, it comforted everyone else. Fans took the songs as survival manuals, lullabies, and eulogies. You Don’t Know How It Feels became a crowd favourite with its weary, wry invitation; audiences regularly shouted out the ‘Let’s roll another joint’ line at Heartbreakers shows.

People loved Wildflowers because it felt as if Petty had stopped playing rock star and started playing human being. He wasn’t the general barking anthems any more, he was one of us, lost, hurting, trying to figure it out. And with that unvarnished honesty, he gave his listeners permission to do the same.

When Wildflowers finally came out in November 1994, it went platinum faster than any other album in etty’s career. But the real victory wasn’t in the sales figures, it was in how deeply the songs sank into people’s lives. This wasn’t just music for car radios or stadium singalongs. It was music that people carried with them into break-ups, recoveries, long nights and quiet mornings.

Over the years, Wildflowers turned into the record people used to measure themselves against. Its lyrics appeared in yearbooks, tattoos, even etched into stone. The title track has been played graveside more times than anyone can count.

After Petty’s death in 2017, Heartbreakers drummer Steve Ferrone (who replaced Stan Lynch during the recording of the album) had the line ‘Most things I worry about never happen anyway’ from Crawling Back To You tattooed on his forearm. Which was a clear break with protocol, since Petty used to joke that none of the Heartbreakers had tattoos, nor were they allowed to get tattoos as long as they were in the band. (None of them except Ferrone ever did.)

Part of the afterlife of this album, and Petty himself, comes from what was left unsaid. Fans knew there was more – the missing half of the double album. In 2020, Wildflowers & All the Rest revealed the breadth of Petty’s vision: 25 songs, each one carrying a fragment of the man at his rawest. Hearing them together was like finding the missing pages of a diary you’d read your whole life but never fully understood.

And then came the film. Mary Wharton’s Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making Of Wildflowers stitched those unearthed reels of 16mm film into a portrait of Petty, then found some more. Releasing another 30 minutes of footage of Petty being interviewed – something he mostly hated – this year and making the film available in Blu-ray helped complete the picture of a great many people’s favourite rock star. The one who bridged the gap between the common man and the superstars who live in Valhalla. The one who was like the rest of us.

That’s why Wildflowers lives on. It’s not the loudest record in his catalogue, not the one with the biggest hits. But it’s the one that feels closest to the bone. Thirty years later, people still press play and hear themselves in it – the sadness, the humour, the hope. Tom Petty thought he was just making another record. Instead, he left behind a masterpiece that people carry like scripture, a record that still whispers, even now: “You belong somewhere you feel free.”

Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making Of Wallflowers is out now on Blu-ray. Tom Petty: Wildflowers from Genesis Publications is due December 2025. Pre-order the Collector’s and Deluxe edition now.

One of the first women to work in rock journalism, Jaan Uhelszki got her start alongside Lester Bangs, Ben Edmonds and Dave Marsh — considered the “dream team” of rock writing at Creem Magazine in the mid-1970s. Currently an Editor at Large at Relix, Uhelszki has published articles in NME, Mojo, Rolling Stone, USA Today, Classic Rock, Uncut and the San Francisco Chronicle. Her awards include Online Journalist of the Year and the National Feature Writer Award from the Music Journalist’s Association, and three Deems Taylor Awards. She is listed in Flavorwire’s 33 Women Music Critics You Need to Read and holds the dubious honour of being the only rock journalist who has ever performed in full costume and makeup with Kiss.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

![Tom Petty - You Don't Know How It Feels [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/ygfA1A45tn8/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Tom Petty - You Wreck Me [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/-3aGZZueg08/maxresdefault.jpg)

![Tom Petty - It's Good To Be King [Official Music Video] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/2SF1iLXSQto/maxresdefault.jpg)