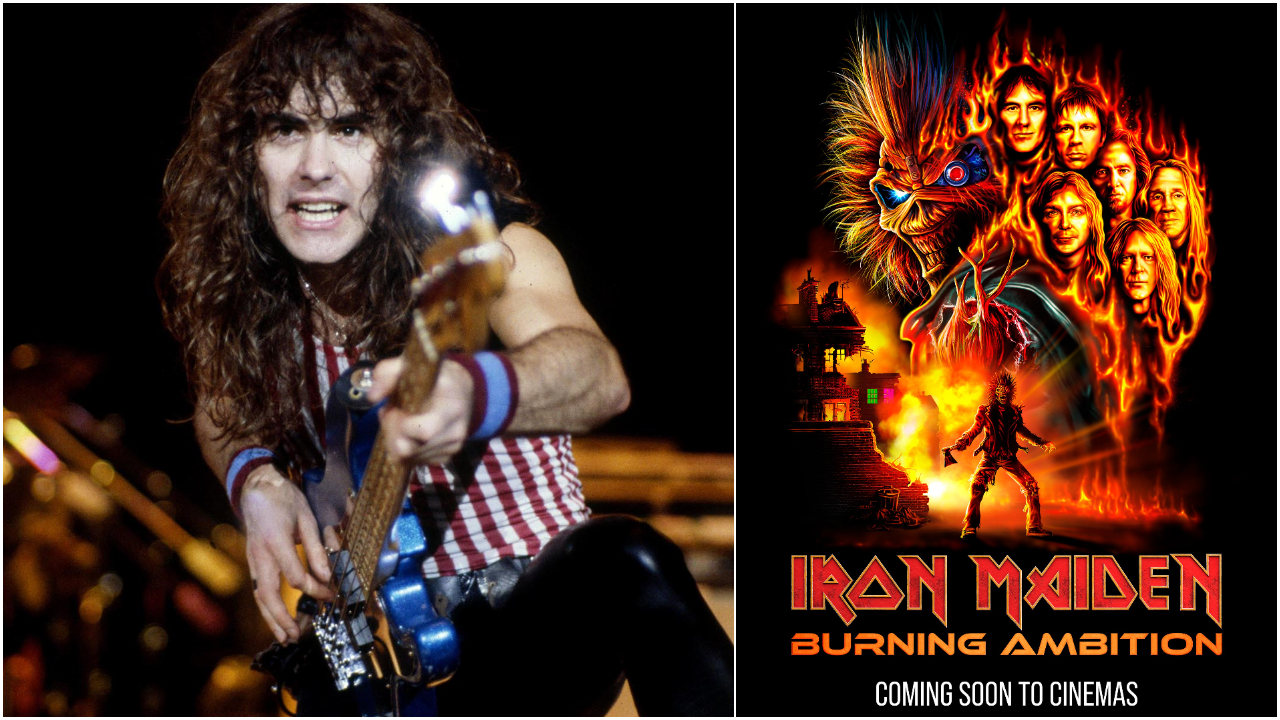

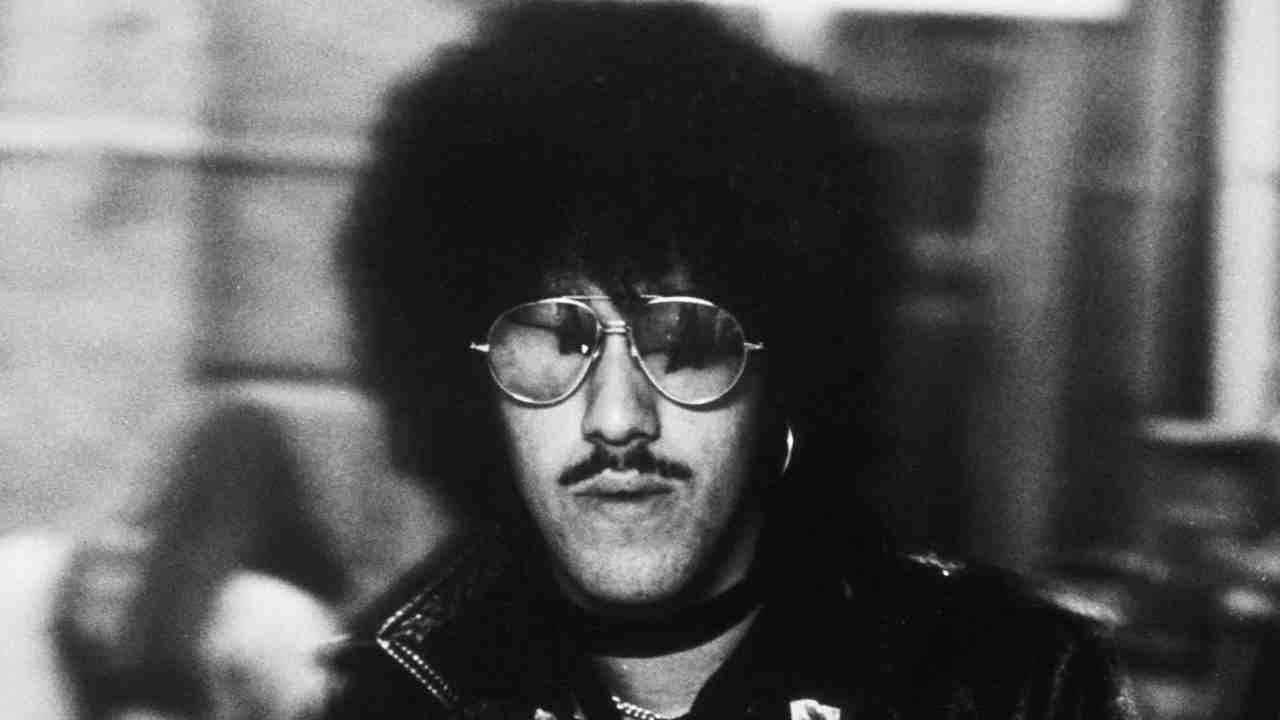

“We were absolutely convinced we were gonna just kill in the US. Then Phil gets hepatitis and – boom! – the tour just stopped there”: A metal fan’s guide to Thin Lizzy, the hellraising 70s rock icons who inspired Metallica and Megadeth

The late, great Phil Lynott and his band inspired many modern metal icons

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Thin Lizzy may not exert the same influence on subsequent generations of metal bands as Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, but their outlaw cool has trickled down. Everyone from Metallica, Megadeth and Anthrax to Mastodon, The Smashing Pumpkins and Vader have covered their songs.

All the greatest rock bands through history have cultivated a wild, outlaw image. But Thin Lizzy didn’t just sing about it, they lived it.

“Can you fight?” their poet-warrior leader Phil Lynott would ask prospective roadies. Not ‘Have you done the job before?’ It was assumed that no one who wasn’t already tip-fucking-top at their shit would be foolish enough to apply for a gig with The Big Fella.

Just: “Can you fight?” And if the answer was in the negative the interview ended there. If you could answer in the affirmative, however, you were invited to join what was, at its peak, the roughest, toughest, gang of nightriders that ever burned down a town.

What really made Thin Lizzy great, though, was how well their music matched that devil-may-care image. Best-known now for The Boys Are Back In Town, a self-mythologising gang anthem that summed up everything great about Thin Lizzy in four minutes of blissed-out bad boy cool, there are many other, even more revelatory moments to draw inspiration from.

Like Jailbreak, the best looking-for-trouble song of its generation. Like Emerald, a modern Irish rebel song that spoke to everybody that ever decided to say ‘fuck it’, and fight back. Like Bad Reputation, a song about tough luck and too much rough stuff.

But then, just to prove there was a soft Celtic heart beating behind that bottle-wielding exterior, there were songs like Sarah, about the birth of Phil Lynott’s beloved first child, and Still In Love With You, one of the most painfully exquisite lost-love songs in the entire rock pantheon.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

This was no mere hellraising metal band. This was big boy stuff. The kind that came from under the counter, sold only to those who knew the right words. This was real. So real it became a story that ended judderingly, first in violent splits and then, finally, in the drug-riddled death of Phil himself, aged just 36, having lived the life of two men, the rare black rose whose dagger-like thorns had finally been blunted.

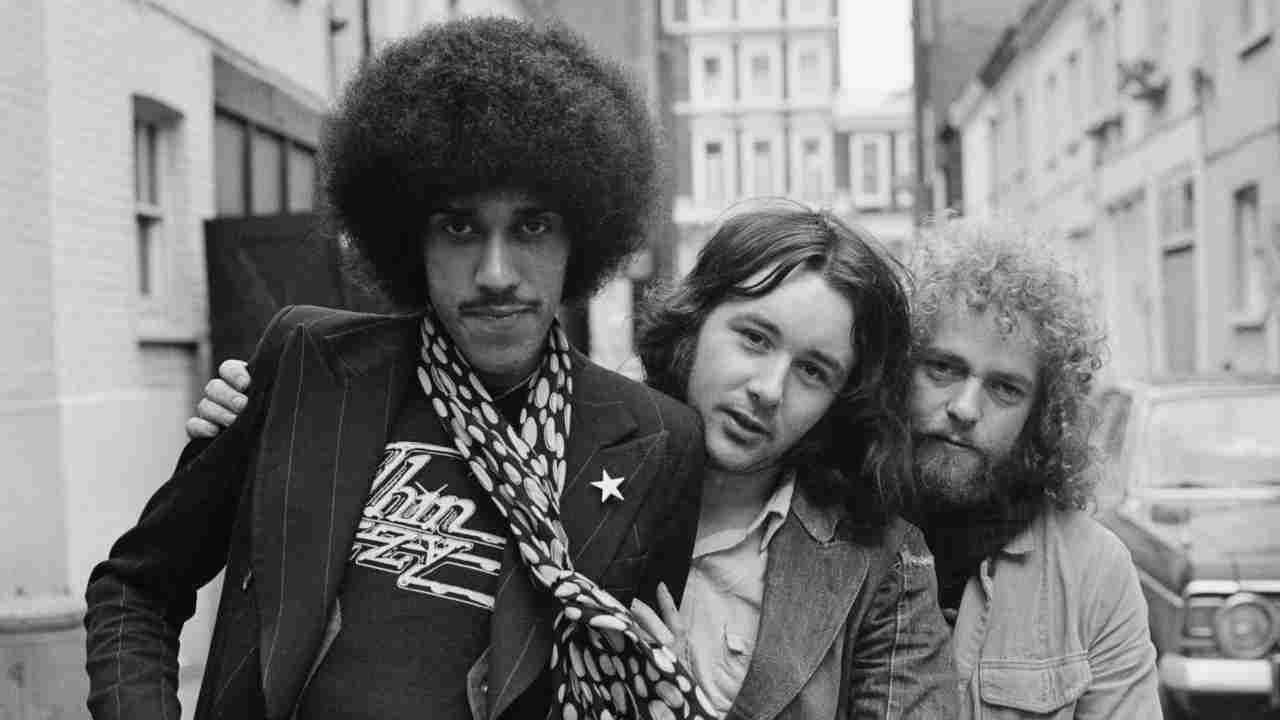

The roots of the Thin Lizzy story go back to the mid-1960s, where two school pals, Philip Lynott – the illegitimate son of a white Irish mother and a black Brazilian merchant seaman – and Brian Downey, his quietly spoken yet tough-as-nails sidekick, formed a band together called The Black Eagles.

Already veterans of the Dublin folk scene – the only music available then in Irish clubs that didn’t comprise Top 40 ‘show bands’ – within a short space of time they had passed through the ranks of Karma Sutra, Skid Row and Orphanage before forming Thin Lizzy in 1970.

The line-up was completed by Belfast-born guitarist Eric Bell, who had played briefly with Them and Van Morrison. Parlophone were quick to offer the increasingly heavy trio a deal that lasted for one ill-fated single, The Farmer, which sold fewer than 300 copies.

The recruitment, in 1971, of a new manager, however, led to a deal with Decca and the band’s first trip to London where they recorded their self-titled debut, again reflecting Phil’s love of “the ole country” on tracks like Dublin and Eire, as well as the basement bar his mother Philomena presided over, on the track Clifton Grange Hotel.

“When we formed Lizzy with Eric one of the conditions that Phil had was that he wanted to play bass and wanted to play some of his own tunes,” recalls Brian Downey.

Live they would play covers of Faces, Cream, Jimi Hendrix and Free. But it was their own unique mix of Irish traditional music and hard rock that made them stand out. The Irish sound “was a hangover from Orphanage,” explains Brian. And in those early days “Phil and Eric would still go and play the folk clubs to pay the rent.”

And so Brian developed a percussive drum style drawing from his love of the bodhrán, the Celtic battle drum. “I never really mastered it but it was tailor made for tom-tom rhythms. And some of these things ended up on the albums.”

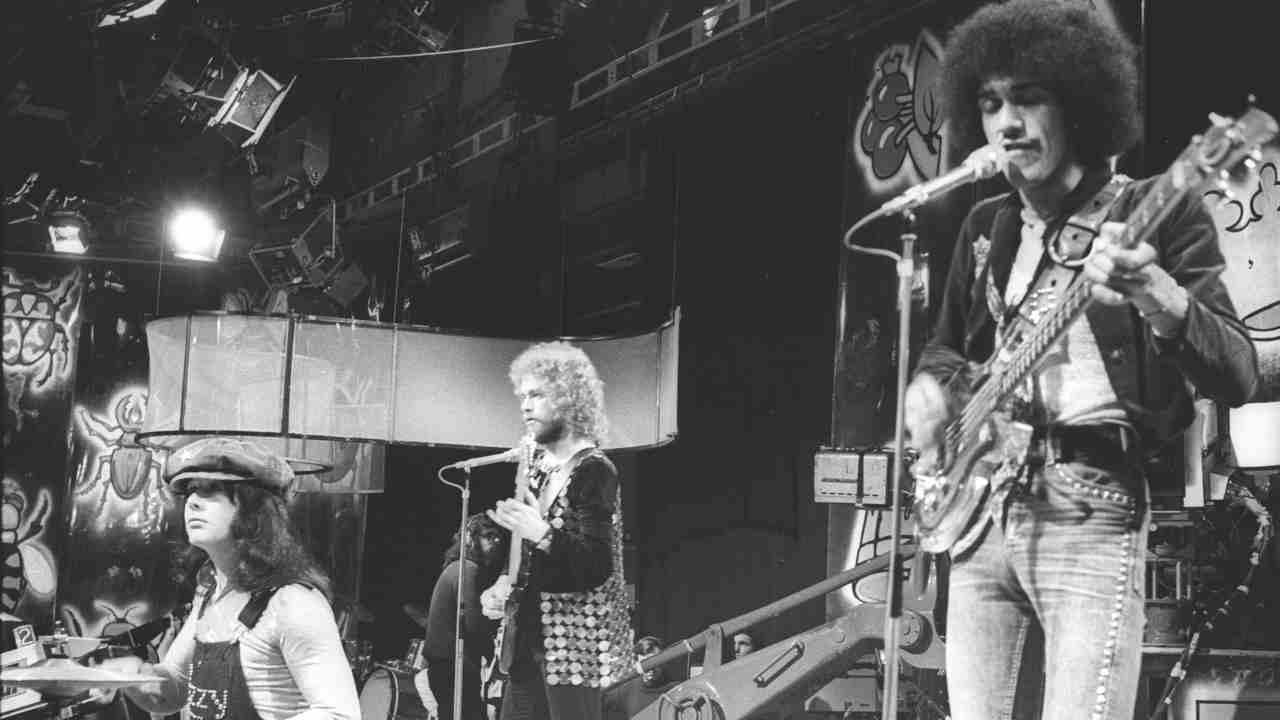

That first album was not a success but it did allow Lizzy to play ‘across the water’ on the UK mainland. “We’d be playing some club and people would be just chatting and drinking, not paying attention.”

It wasn’t until their second album, Shades Of A Blue Orphanage, that the name Thin Lizzy began appearing in the influential UK music press. They even landed third spot on a big tour, headlined by Slade and Suzi Quatro. Again, though, this proved a mixed blessing.

“Especially in Liverpool where we got bottled off the stage. It was a big boxing stadium and you had to go through the crowd to reach the stage. Getting off I thought we were going to get killed.”

They would go back to Ireland to make money then return to struggling on the UK club circuit. But despite containing some truly epic moments like the seven-minute-plus opener The Rise And Dear Demise Of The Funky Nomadic Tribes – a genuinely weird but affecting mix of groovacious rock, lowdown funk and oddly sinister Celtic rhythms – Shades… refused to sell.

“We’d get to gigs and Phil would be coming up with all sorts of ideas during the soundcheck. He was writing a lot of poetry and those ideas definitely came through in the lyrics, a lot of which were really stories.”

This approach reached its apotheosis with the band’s third album, Vagabonds Of The Western World, a loosely conceptual work that moved their Celtic rock into dizzying psychedelic freak-outs (The Hero And The Villain), moody rockers (The Rocker), heartfelt love songs (Little Girl In Bloom) and haunting Celtic rock epics like the blistering title track.

However, as Brian says, “The pressure was really on by then. A lot of A&R men from Decca started saying it would be nice to get a single in the charts. That was the time Phil started to think commercially.”

The result was a slinky Jimi Hendrix-style track called Black Boys On The Corner, written as an A-side for a standalone single upfront of the album, but flipped by the Decca suits when the greater commercial appeal of the B-side, a re-worked traditional Irish tune titled Whiskey In The Jar, became evident.

In March 1973, Whiskey In The Jar, already number one in Ireland, reached number six in the UK and suddenly it seemed like Lizzy were on their way.

Once again, though, things didn’t work out as planned. When Vagabonds… failed to make the charts again, Decca threw in the towel and dropped them.

Despondent, Eric Bell walked out at a New Year’s Eve show in Belfast, in December 1973. “Eric threw his guitar up in the air and it came smashing down,” says Brian. “We ended up doing the final 45 minutes on our own. Thankfully the students were all pissed too. That’s the only reason we got out alive.”

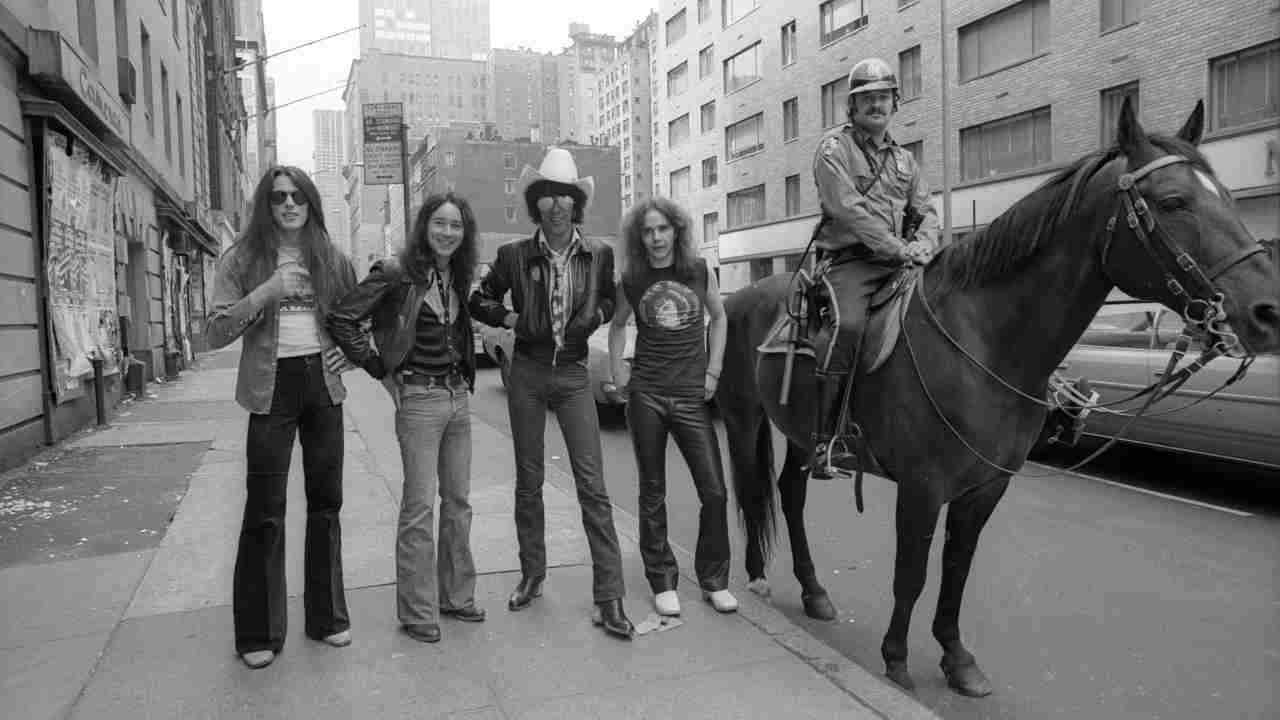

Yet out of this all-time low came the breakthrough they had been waiting for with the recruitment of two new gun-for-hire guitarists in 17-year-old Brian ‘Robbo’ Robertson and 20-year-old American Scott Gorham.

Robbo was a multitalented former public schoolboy and Lizzy fan from Glasgow who’d studied cello and classical piano before switching to rock drums and guitar.

“He was quieter when he joined the band,” recalls Brian, “but

it was only a temporary period of being a good boy. It didn’t take him long to start a ruckus.”

Scott was a college drop-out from Glendale, California, who had travelled to London on the half-promise of a try-out for pomp rockers Supertramp. When that failed to materialise he began simply “jamming in pubs in London”. He had 30 days left on his tourist visa when he heard about the Lizzy auditions.

“He had the longest hair I’d ever seen,” chuckles Brian. “I thought, ‘Wow, this guy really looks the part’. Until he opened his guitar case and out came a Japanese Les Paul copy. Then he started to play and he didn’t sound like a blues guitar player. He sounded more west coast, American psychedelic kind of a guy. I’d never played with anyone like that before.”

Thus was born the classic twin-guitar four-piece that would record the next six Thin Lizzy albums, not a dud amongst them. There was never any doubt over who ran the show, though.

Scott: “Me and Robbo were like, ‘Absolutely, Phil, whatever you say.’ Music, clothes, where you stood onstage, everything.”

But when their first two albums with the new line-up, Nightlife (1974) and Fighting (1975), again flopped, Scott says it was only “Phil’s unbelievable drive” that kept them together afterwards.

Scott now characterises Nightlife as “a cocktail album”. True, its surprising shift to a more funk-tinged ambience was a surprise but it also contained the template for future Lizzy greatness in tracks like the opener She Knows – the first song Scott ever wrote with Phil.

But Fighting was more like it, marking the real start of the band’s ascent to greatness.

“The twin guitar thing started when Robbo was doing a guitar line and the engineer accidentally put a millisecond delay on it, so that when the guitar came back it started to harmonise itself. We went, wait a minute, that sounded pretty cool.’ I told Robbo, ‘Why don’t you go out there and do the line again and I’ll sit here and learn the harmony to it’.”

Fighting also contained Phil’s self-mythologising Ballad Of A Hard Man. But behind the public persona of the charismatic leader who, according to Scott, “could screw more chicks, drink more drinks, take more drugs, stay up more nights in a row than anybody I ever met before”, there was a man who would one day become trapped by his own tough guy image.

The full-blown Thin Lizzy finally emerged on 1976’s Jailbreak album. Wrapped in a futuristic Jim Fitzpatrick sleeve, the album’s title track’s outlaw imagery would permeate every album Lizzy would make from now on.

And of course there was The Boys Are Back In Town. “It almost didn’t make it on the album,” says Scott now. “At that point it didn’t have a guitar riff that was killing everybody. But we all liked the lyrics. Originally it had been some kind of war song but Phil kept reworking the lyrics and one day he just came up with the phrase: the boys are back in town. And that kind of juiced everybody up.”

The creative juices were still flowing on their next album, Johnny The Fox, released just six months later. “Jailbreak and Johnny The Fox could have been a double-album. During that really focused Jailbreak period, we had written so many songs.”

It even had the perfect follow-up to The Boys Are Back In Town in the rip-roaring Don’t Believe A Word. “We used to play it as more of a ballad.” Then one day while Phil was out, Robbo came up with the riff. Not that he ever got credited, something that stuck in his craw.

By then, however, Robbo and Phil were at loggerheads anyway. Jailbreak had reached the US Top 20, as had The Boys Are Back In Town. To capitalise, a high-profile tour was arranged, co-headlining with Queen. Billed as the Queen Lizzy tour, it should have been their big breakthrough.

Instead, it turned to disaster when Robbo got into a fight on the eve of the tour during which his left hand was cut by a broken bottle, severing tendons and making it impossible for him to play.

“That was the start of what I call the Curse Of Thin Lizzy,” says Scott with a sigh.

With Belfast-born Gary Moore coming to replace Robbo temporarily, the tour then ran into further trouble.

“We were on the bill with Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow and we were absolutely convinced we were gonna just kill. Then Phil gets hepatitis and – boom! – we run into another USA brick wall. The tour just stopped there.”

Instead the band was rushed into a studio in Toronto for their next album, Bad Reputation – with Scott now playing all the guitars. At its end Scott had even talked Phil into letting Robbo back in the band. Inevitably, it did not last.

“After a few drinks, the Scotsman would come out of Robbo,” says Brian Downey. “Then, after a few drinks more, the Irishman would come out in me and Phil.”

Before Robbo was fired for the second and final time in 1978, however, the band release what became their greatest album of all, the double Live And Dangerous. “We needed this to show everybody what Thin Lizzy was really all about. This is the energy we create. This is what happens when we play live, and it’s a lot different from any of the studio albums.”

As a result, Live And Dangerous became Lizzy’s biggest selling album. Success, however, would have its price.

There would be one more great album, Black Rose, recorded with Gary Moore back in for Robbo. But a tipping point had been reached. Scott recalls their first rehearsal. “When Gary strapped on the guitar and started playing, it was, ‘Holy shit! This guy’s gonna dust me, man!’”

It wasn’t the music that separated them, though, as much as the drugs. “Gary was totally on the other side: no drink, no drugs,” says Scott.

The Black Rose sessions in Paris were also the first time the band became involved in heroin. Scott laughingly recalls how Cliff Richard, who was recording an album next-door, was invited in. “Cliff’s sitting bolt upright in the chair facing the speakers. And right behind him are two dealers chopping out smack. That’s just a small measure of how crazy it got.”

The chickens came home to roost, though, when Gary walked out in the summer of 1979 – midway through yet another disastrous US tour. Having fired Robbo for being out of control, Gary now fired the band – for the same reason.

“Phil went from being the first guy in the studio and the last guy out, a workaholic,” said Moore, “to starting each day on Black Rose with a joint in one hand and a whiskey in the other.”

Phil’s house in Kew was also a magnet for London’s inelegantly wasted. Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen were frequent visitors, where a now-famous photo of the pair was taken in the toilet. According to Gary Moore: “Phil used to say, ‘That fucking Sid, he comes round here shooting up, drops the needle on the floor, picks it up and sticks it straight back in his arm…’”

“Nobody chained Phil down and forced him to take drugs,” says Scott. “Only now he’s a star, he’s got a lot to live up to, the big image. How do you keep that train rolling? Well, there’s a line of jump juice over there, you know? How bad can it hurt?”

Their 1980 album, Chinatown, found Scott paired up with session wizard Snowy White. An exceptional player who’d toured with Pink Floyd, while White matched Moore’s cohesive style, he lacked his or Robbo’s dynamic onstage energy. A character he was not. The result was an album that, while still yielding two hits in the title track and Killer On The Loose, found the band creatively treading water.

“It wasn’t Snowy’s fault,” insists Scott. “He could see Phil and I were so strung out it was ridiculous.”

As a result their next – and last – album with Snowy, Renegade, became the first Lizzy album not to make the charts for seven years. The end was nigh, even though Phil refused to accept it. There would be one final album, ironically their best for years, Thunder And Lightning, but according to Scott, Lizzy was already over long before then.

“I was still horribly strung-out on heroin and so was Phil. It was a really, really tough decision for me to quit but I had to. Phil was shocked, saying, ‘Anybody else can leave but you can’t leave.’ But I said, ‘Phil, I can’t physically do it anymore. I’m just fucked’.

Had the story of Thin Lizzy ended there it would have been sad but at least it could be said they went out at those final shows in a blaze of glory. Instead there was to be a tragic coda.

After Lizzy finally broke up, Brian Downey retreated to Ireland while Scott Gorham headed back to California and into rehab. Late in 1985 he returned to London to visit Phil.

“He was still a mess… talking about how we should write songs, get the band back together… I’m looking at him thinking, ‘Phil, you’re not gonna make it, man.’ That was literally the last time I saw him. Three weeks later I got the call – massive heart attack, intensive care, emergency hospital, pipes coming out of everywhere. He had contracted septicaemia, his liver was failing but it was the heart attack ultimately in the end that got him.”

Phil Lynott died on January 4, 1986. The cocky, charismatic kid who had the world at his feet nearly 20 years earlier had become a casualty of rock’n’roll. There have been relaunched, Lynott-free version of the band in recent years, but none could truly capture the magic of the past. Lynott may be gone, but the boys will forever be back in town.

Originally published in Metal Hammer 223 (September 2011)

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.