The triumph of the gentleman rockers: How Led Zeppelin IV was made

In 1971, Led Zeppelin released their untitled fourth album and changed the face of rock forever. This is the story of the album known variously as Led Zeppelin IV, Runes, Four Symbols or simply Untitled

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

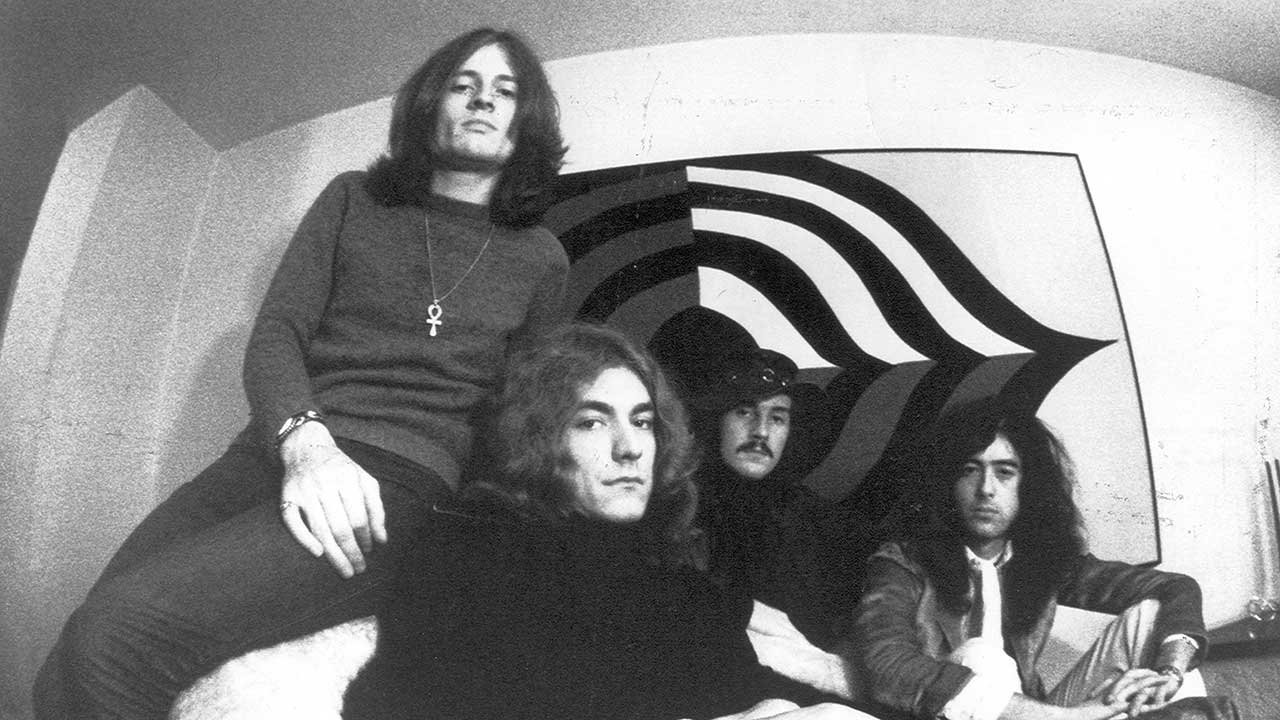

On a bitterly cold morning in January 1971, guitarist Jimmy Page, 26, singer Robert Plant, 22, bassist/ keyboardist John Paul Jones, 24, and drummer John Bonham, 22, arrived at Headley Grange, Hampshire, to find the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio already waiting for them in the driveway.

With them was a young engineer by the name of Andy Johns, brother of Glyn, who had worked on the first Zeppelin album, piano player Ian Stewart, formerly piano player and jack-of-all-trades for the Rolling Stones, and known to all and sundry as Stu, along with a small road crew.

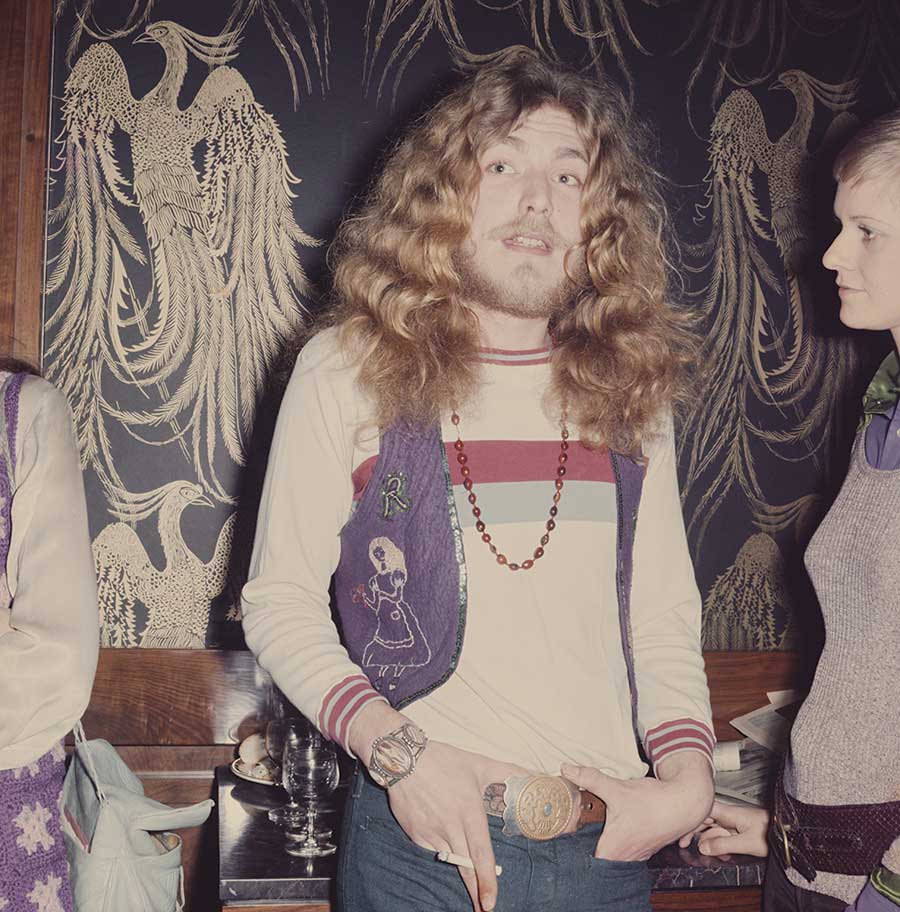

Plant and Page, in the grip of an intense and productive creative union, fell into that group of artists whose muse was susceptible to their surroundings. The damp, cool manor, with its bleak history, surrounded by the bare winter trees, affected them quickly.

Article continues below“Most of the mood for the fourth album was brought about in settings we had not been used to,” Plant later reflected. “We were living in this falling-down mansion in the country. It was incredible.”

That opinion, though, was not universally held among the group: “It was cold and damp,” recalls Jones. “We all ran in when we arrived in a mad scramble to get the driest rooms. There was no pool table or pub. It was just so dull."

So it was that, 140 years after it was ransacked by several hundred mad rioters, Headley Grange took up its role in the making of the most famous and most imitated rock record in history. By the time the band began to think seriously about material for their fourth album, Led Zeppelin, it seemed, could do almost what they wanted. It didn’t matter what the critics said, Zep were now big enough to take the knocks.

Manager Peter Grant was not given to taking chances, however, and in a typically farsighted move, he effectively took the band off the road during the latter half of 1970, in order to allow them the space they needed to come up with something fresh again.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

In late October 1970 Page and Plant had returned to Bron-Yr-Aur, the idyllic cottage halfway up a mountain in south Snowdonia. It was here that earlier in the year they had conceived many of the songs for Led Zeppelin III. As before, they sat around the cottage hearth with a decent log fire burning and played and sang. They already had a backlog of half-finished songs and fragments of ideas. Among them was a lilting Neil Young-influenced piece titled Down By The Seaside and two semi-acoustic tunes, Hey, Hey What Can I Do and Poor Tom.

In December they booked initial studio sessions at Island Studios. The Basing Street location was becoming the most in-demand studio in London and they had recorded much of III there. Page, though, was also looking to record on location with The Rolling Stones’ new mobile recording unit.

“We started off doing some tracks at Island, then we went to Headley Grange,” he recalled. “We took the Stones’ mobile . It was ideal. As soon as we had an idea we put it down on tape.”

The group began to settle in at Headley Grange, Page and Plant revelling in the atmosphere which was so different from the sterile surrounds of a normal studio. It was the idyll of the early 70s; gentleman rockers at large in the country, gear set up for extended jams, and some sedate – by Zeppelin’s Herculean standards, at any rate – recreation on hand.

Tour manager Richard Cole noted: “There weren’t any serious drugs around the band at that point, just dope and a bit of coke. Mostly we had an account at a shop in the village and we’d go down there and collect large quantities of cider. They were playing at being country squires. They found an old shotgun and used to shoot at squirrels in the woods. Not that they ever hit any. And there was this lovely old black Labrador dog wandering around which we used to feed.”

Each day, the band and Ian Stewart would gather downstairs and jam. Significantly, Stu had included his battered old upright piano in his luggage. He quickly assumed the same role he had with the Stones: a terrific, bluesy piano player with a particular feel for old-style rock’n’roll. But if Stu’s involvement was partly accidental, serendipity surrounded the making of the whole album.

In the middle of an early session, John Bonham began banging out the cymbal-led introduction to Little Richard’s Keep A-Knockin’. Stu playfully added a Jerry Lee Lewis roadhouse piano riff and Page and Jones picked up the ball and ran with it, knocking out a riff based on old Sun Records-era Scotty Moore guitar lines. Plant cut in with his own improvisation, and rather than trip into a rock’n’roll standard he began wailing nonsense lyrics built around a chorus of ‘It’s been a long time since I rock’n’rolled, mama!’

The lightbulbs went on. “We were doing something else at the time but Bonzo played the beginning of a Little Richard track. We had the tape running and I started doing that part of the riff,” Jimmy remembered. “It ground to a halt after 12 bars but we knew we had something. Robert came in with the lyrics and within 15 minutes the song was virtually complete.”

When they began playing the track in their live set during their European and US dates later that year, Plant introduced the tune under the title It’s Been A Long Time. After they had latterly settled on the more straightforward title, Rock And Roll would open Zeppelin’s live show from late 1972 through to 1975. But if Headley Grange was big on atmosphere, its aged walls also brought other, less expected advantages. The hallway was known as the Minstrel’s Gallery. The sound bounced around a natural bowl, and echoed back up the three flights of stairs.

“The other guys were out having a drink and John Bonham and I were at the house,” recalls Andy Johns. “He complained that he wasn’t getting the sound he wanted. I finally said to him, I’ve got an idea. We got his drums and put him in the hallway and then hung two mikes from the staircase and pointed them towards the kit.

“I remember sitting there thinking it sounded utterly amazing, so I ran out of the truck and said, ‘Bonzo, you gotta come in and hear this!’ He shouted: ‘Whoah, that’s it! That’s what I’ve been hearing!’”

Page was equally enthusiastic: “What you’re hearing on the record is the sound of the hall with the stereo mic on the stairs second flight up. There was a lot of different effects in there. Phased vocal and a backwards-echoed harmonica solo. I’d used backwards echo as far back as the Yardbirds’ days.”

Decades on, Bonham’s performance on When The Levee Breaks, an old Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy recording that Zeppelin rearranged quite radically into a narcotic, blues rock colossus, has become the most sampled drum sound of all time, first taken by the likes of the Beastie Boys and the house music DJs in the late 80s, it has been used on hundreds of rap and dance tunes. It has been speeded up, slowed down, distorted, stretched and condensed, and it remains one of the most startling percussive statements ever committed to tape.

Otherwise, Page remembers When The Levee Breaks being a difficult track to record: “We tried to record that in the studio before we got to Headley Grange and it sounded flat. But once we got the drum sound at Headley Grange it was like – boom! And that made the difference immediately.”

The sessions for the fourth Zeppelin album continued to develop organically. They were still drawing liberally from Page and Plant’s blues influences and were increasingly drawn towards the folk sounds that had either enthralled, enraged or confused those listening to Led Zeppelin III.

John Paul Jones had used a mandolin on That’s The Way on III, and he brought it to the Grange. Page was sitting around downstairs late one night and, “These chords just came out. It was my first experiment with the mandolin. I suppose mandolin players would laugh, because it must be the standard thing to play those chords, but possibly not with that approach. It did sound a little like a ‘let’s dance around the Maypole number’ but it wasn’t purposely like that.”

Plant had written the lyric for The Battle Of Evermore after reading a book on the Scottish wars. But he felt the tune needed another vocalist to act as a foil and so the band called on ex-Fairport Convention singer Sandy Denny to provide a rare cameo.

“It’s really more of a playlet than a song,” says Plant. “After I wrote the lyrics I realised I needed another completely different voice as well to give the song full impact. So while I sang the events in the song, Sandy answered back as if she was the pulse of the people on the battlements. Denny was playing the town crier urging people to throw down their weapons.”

At Headley Grange, Plant sang a guide vocal, leaving the response lines for Denny to insert later. Denny noted Plant’s prowess as a vocalist on the session: “We started out soft but I was hoarse by the end, trying to keep up with him.”

The richness of the Bron-Yr-Aur sessions was also apparent. Although Page and Plant had written The Battle Of Evermore on the run at the Grange, other songs that took the same remit of acoustic guitar, mandolin and traditional influence had begun in Snowdonia. Going To California was written there and recorded later at the Grange. Other, more random factors were at work, too. Like the old black dog that used to hang around the Grange’s kitchen.

“We didn’t know his name, we just used to call him Black Dog,” Jimmy recalls. When the dog went missing one night, only to return and spend the whole of the next day sleeping it off, John Paul Jones decided “it was the perfect image” for a barrelrollin’ riff he was noodling with. The result: one of the most swaggering, psycho-sexual monsters in the Zep canon: Black Dog.

“Black Dog is definitely one of my favourite riffs,” recalls Jones. “It was originally all in 3/16 time but no one could keep up with that!”

Plant’s a capella vocal between the riffs was an arrangement Page had adapted from Fleetwood Mac’s Oh Well. Jimmy’s fade-out solo was a cleverly overdubbed; a triple-tracked guitar solo pieced together by splicing four different passages. So taut were the sounds, Jimmy recalls the guitars sounding like “an analog synthesiser” when he reviewed the tapes for the Remasters series.

A combination of 4/4 time set against 5/4, the peacocking, lugubrious riff to Black Dog was a key indication of how far ahead of the game Zeppelin really were. While then newcomers like Grand Funk Railroad were busy building successful careers by distilling the hard-edged electric blues of Led Zeppelin II into something more easily palatable but infinitely less interesting, Zeppelin had already moved on. A fact that would become most evident upon the fourth album’s release, in the second week of November, 1971.

The reputations of Led Zeppelin’s four members have long been cast in rhetorical stone. Page as the virtuoso embodiment of the band’s creative spirit; Plant as the sexual, sinuous rock god; Jones as the scholarly muso; and John Bonham as the take-no-prisoners, hard-living, party animal. And yet as inspired and inventive as songwriters as Page, Plant and Jones were, and are, so Bonham was their equal as a musician, and as an important musical ‘voice’ in the band. His influence cannot be overstated, and nowhere more so than on the fourth album, where his contribution went way beyond his natural power and newly-discovered drum sound.

Bonham’s work on every track was superbly applied, and no more so than his dropping off the beat at 4 minutes 17 seconds into Misty Mountain Hop, the album’s nod to the medicinal properties of good, strong weed. Elsewhere on the album, Jones had an electric synth riff that the band were unable to nail until Bonham laid down a can of Double Diamond (much maligned and now forgotten workingman’s brew), picked up two drumsticks in each hand and, as Jimmy Page remembers, “just went for it. It was magic. We had tried different ways of approaching it. The idea was to get an abstract feeling. We tried it a few times and it didn’t come off until the day Bonzo did that.”

In a nod to John’s genius, the band decided to call the song Four Sticks. “It was a bastard to mix,” says Andy Johns.

More than any other Led Zeppelin album though, before or since, the fourth album, would become both glorified and then later vilified, before coming full-circle latterly to be glorified again for one track: Stairway To Heaven. Destined to become one of their two most famous songs (just ahead of Whole Lotta Love), we all know this one.

Still consistently voted one of, if not the, most popular and most widely known rock songs in history – kind of like Bridge Over Troubled Water and Bohemian Rhapsody all rolled into one – it has become the National Anthem of rock music.

Of course, it’s also said to contain beastly goings on if played backwards. And at least one of those involved in its creation, Robert Plant, has subsequently formed a relationship with the song that can only best be described as ambiguous. But when a song assumes such magnitude in people’s minds, the side effects can be strange, for those nearest to it just as much as those who are merely projecting their own thoughts and ideas into the song’s unashamedly metaphysical poetics.

Page had much of the chord sequence on a demo when they first tried it out. “I’d been fooling around with the acoustic guitar and came up with the different sections, which I married together. So I had the structure and then I ran it through Jonesy. I’d had the chord sequence pretty much worked out and Robert came up with about 60 per cent of the lyrics on the spot.”

Andy Johns: “We did the track at Island in London. Jimmy had the tune pretty much worked out. He played acoustic in the isolation booth. He was the thread that held it all together. We had Bonzo out in the main room and John Paul played a Honer electric piano.”

Plant’s lyrics were pieced together very quickly while the band was at Headley Grange. “Jimmy and I stayed up one night and we got the theme of it right there and then,” he recalled. “The lyrics were a cynical thing about a woman getting everything she wanted without giving anything back.”

It was Jones who came up with the memorable opening sequence: “We always had a lot of instruments lying around so I picked up a bass recorder and played along with Jimmy.”

Page took three separate attempts at the heavens-shaking guitar solo which became the orgasmic crescendo of the song; rather than deploy the usual Gibson Les Paul he returned to the battered old Telecaster that he had acquired from Jeff Beck and used on the first Zeppelin album.

"I winged that guitar solo, really. When it came to recording it, I warmed up and did three of them. They were all quite different from each other. I did have the first phrase worked out and then there was the link phrase. I did check them before the tape ran. The one we used was definitely the best.”

The result was one of the only guitar solos in history as likely to be whistled by milkman as air-guitared in the bedroom. And yet the song would become so ubiquitous that it overshadowed a brilliant body of work. As a result, Plant, for one, has an uneasy relationship with Stairway… now.

“There’s only so many times you can sing it and mean it. It just became so sanctimonious,” he said. An attitude that resulted in major row backstage with Page before their televised 1988 Atlantic Records 40th anniversary reunion at Madison Square, in New York Garden. Robert had decided, at the last moment, that he didn’t want to sing it. He finally relented, just before they went on, but the subsequent performance was accordingly dull and uninspired.

Back in 1971, however, it was a song they were both immensely proud of. Talking to Cameron Crowe about it in Rolling Stone in 1975, Jimmy said: “I thought it crystallised the essence of the band. It had everything there and showed us at our best as a band and as a unit. Every musician wants to be able to do something of lasting quality.”

With the initial recording completed by early February, on Andy Johns’ recommendation, he and Page flew with manager Peter Grant to Los Angeles, where the tapes would be mixed at Sunset Sound. Just as they were flying in to LA, the city suffered a minor earthquake. It might have been an omen.

Page remembered: “The funny thing is on Going To California, you’ve got the line ‘Mountains and the canyons started to tremble and shake’ and as we landed there was a mild earthquake. In the hotel room before going to the studio you could feel the bed shake.”

Similarly, the mix did not go as planned, much to the embarrassment of Johns. “I convinced Jimmy to mix it in Los Angeles. We booked time at Sunset Sound, but the room that I’d worked in before had been completely changed. So we used another room there and mixed the entire album. We came back to London and played it back in Studio One at Olympic and it sounded terrible!”

Page was damning at the time: “Basically, Andy Johns should be hung, drawn and quartered for the fiascos he’s played.” But despite the problems, the resulting production was one of Page’s finest. Eventually released On November 8, 1971, the resolutely untitled fourth Led Zeppelin album sailed straight to No. 1 in Britain and stayed there throughout most of December.

Richard Branson’s then newly-established Virgin Records set up special stalls to sell it, demand was so great. It was a similar story in the US, though Carole King’s Tapestry kept it off the No.1 spot. It didn’t matter. The airplay generated by Stairway To Heaven ensured the album remained in the Top 40 of the US album chart for the next six months. The record company had understandably wanted to release it as a single but the band steadfastly refused to allow it.

“We wanted them to hear it in the context of the whole album,” says Page, simply. They never looked back. Led Zeppelin IV, as it inevitably became known, is now confirmed as one of the biggest-selling hard rock album of all time, with sales to date of over 29 million.

Jon Hotten is an English author and journalist. He is best known for the books Muscle: A Writer's Trip Through a Sport with No Boundaries and The Years of the Locust. In June 2015 he published a novel, My Life And The Beautiful Music (Cape), based on his time in LA in the late 80s reporting on the heavy metal scene. He was a contributor to Kerrang! magazine from 1987–92 and currently contributes to Classic Rock. Hotten is the author of the popular cricket blog, The Old Batsman, and since February 2013 is a frequent contributor to The Cordon cricket blog at Cricinfo. His most recent book, Bat, Ball & Field, was published in 2022.