The unstoppable rise of UK proggers Lifesigns

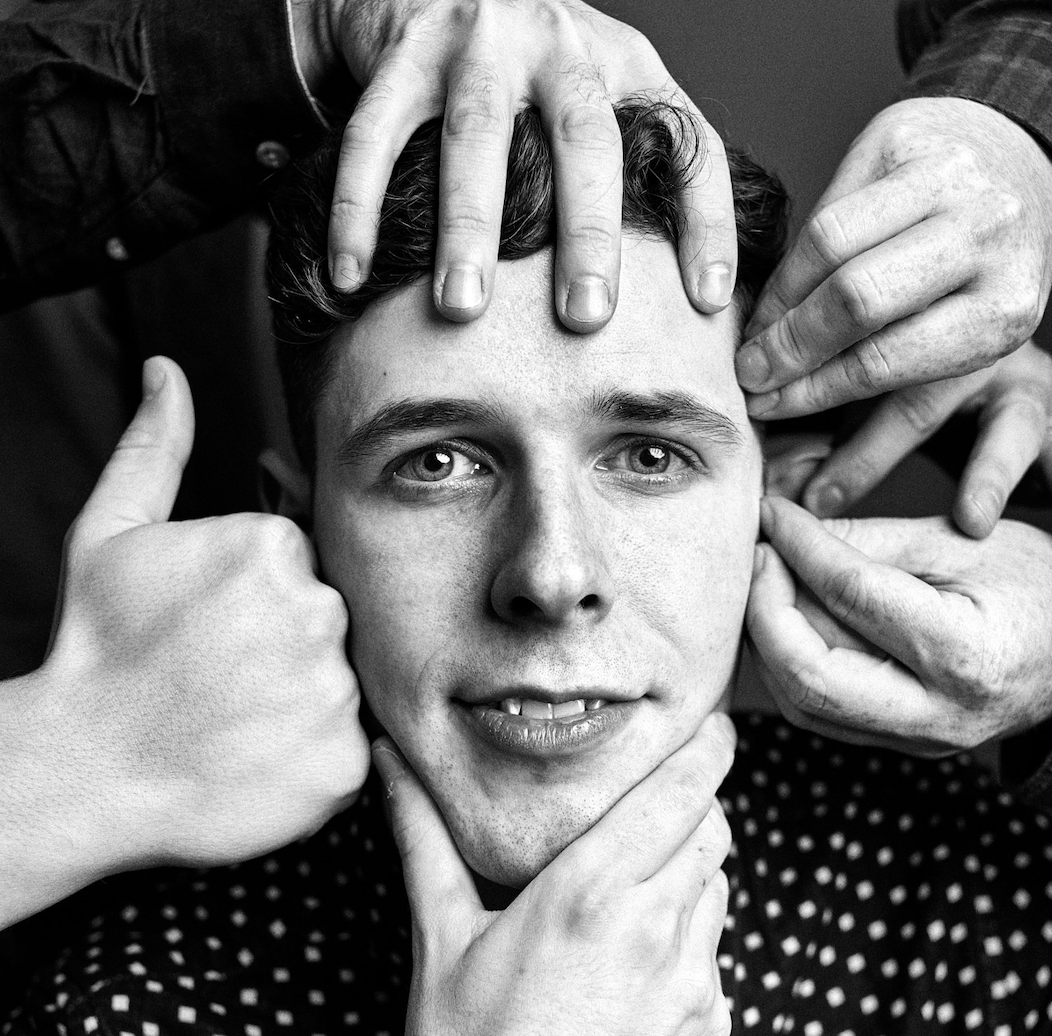

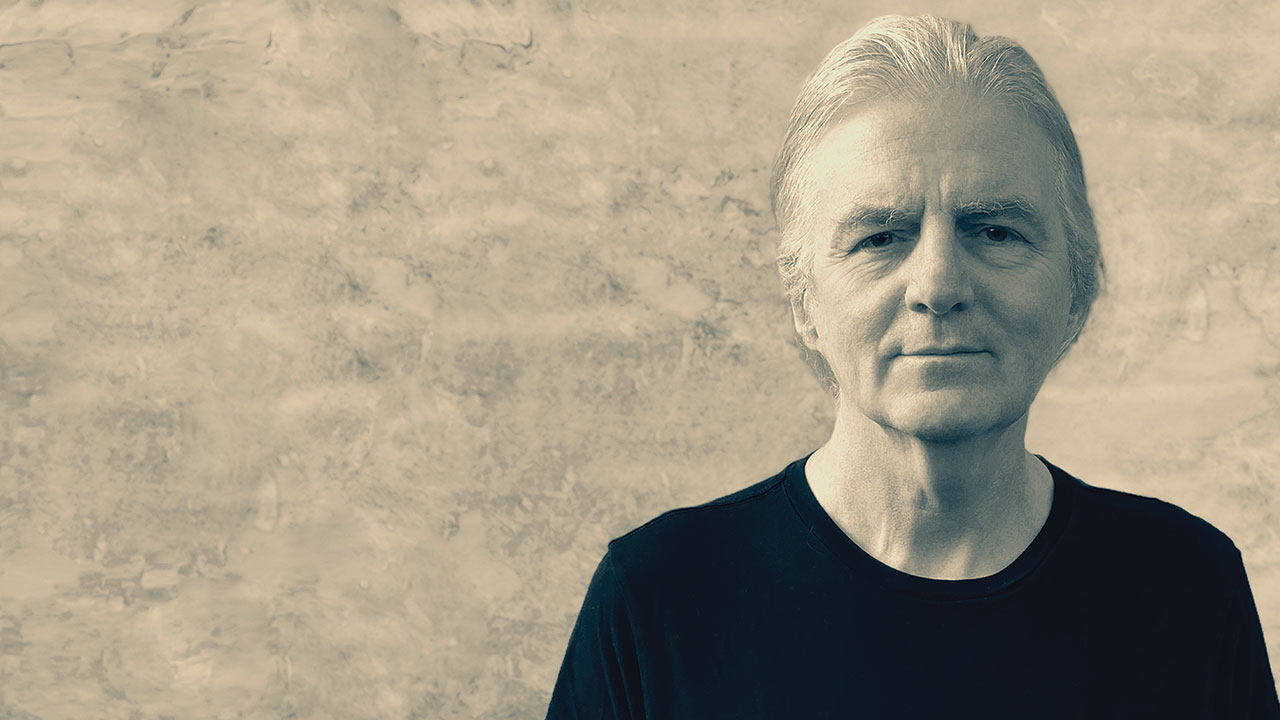

Vocalist and keyboard whizz John Young tells discusses new Lifesigns album Altitude – and why you won’t be finding the full release on Spotify anytime soon!

“Please purchase directly from us to support our independence,” Lifesigns requested via an advert in Prog a few months ago. “No terms and conditions apply.”

The prog rockers’ collective tongue was firmly in cheek when they took out the ad – “we offer solutions to a wide a range of musical yearnings,” they added – but the underlying message was sincere.

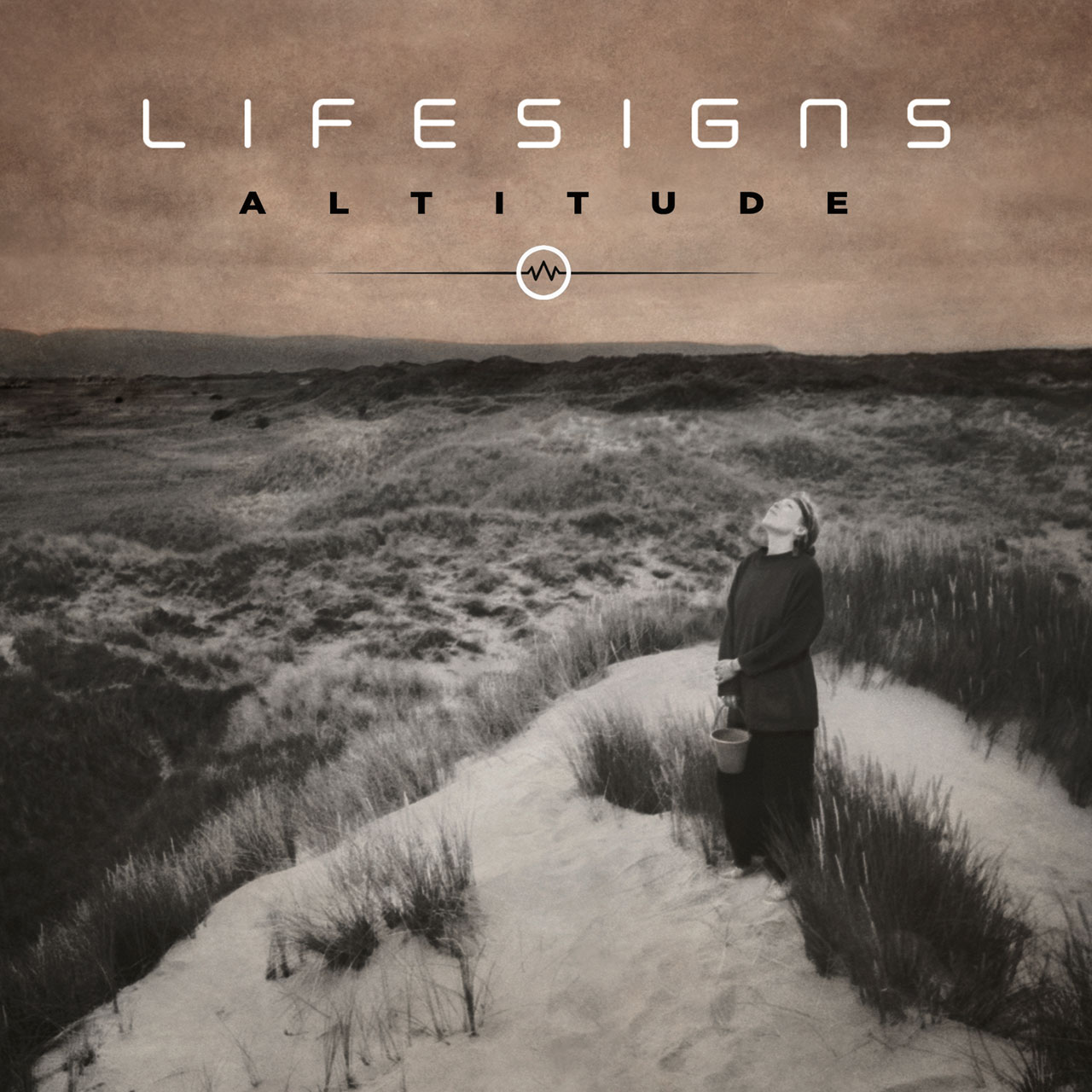

Lifesigns’ third studio album, Altitude, is intrinsically independent in nature: it came to fruition thanks to another crowdfunding campaign. This has led to some tagging them as the ‘new Marillion’, who of course pioneered asking fans to pay up front. The eight-track is what many have come to expect from Lifesigns: thoughtfully written prog rock, which is happy to flirt with major chords, earworm melodies and dexterous playing.

It’s another product of the pandemic, with the band lurching into recording following some shows in March 2020, just as the world was about to grind to a halt. And, like most music making last year, the record was pieced together with contributions that had been zapped around online.

“It was very much back and forth, but the problem you have to an extent is if you’re in the studio you can go, ‘Well, I don’t like that, I could do it again,’” singer and keyboard player John Young explains down the line from his home in Bedfordshire. “Filesharing doesn’t give you that option. Steve [Rispin, sound engineer and co-producer] and I had to be fairly busy with the scissors. Everybody has a say in what’s going on, but in the end the final say comes down to me and Steve because we’re actually making the record.

“Recording took place over about six months, and then we spent a good couple of months mixing. In the end we got exactly what we wanted.”

The result is fit for a spot in this year’s top 20 albums lists. Altitude feels like the sum of its gifted parts; Young and Rispin are joined by core members Jon Poole (bass), Dave Bainbridge (guitar) and Zoltán Csörsz (drums), while cello, violin and backing vocals from Exploring Birdsong’s Lynsey Ward feature too.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Songs such as the 15-minute title track are grand without being overblown, subtle yet skilful. But at their beating heart is progressive adventurism, with nods to fusion this time round, grounded by the weight of stripped-back, finely produced songwriting.

“The musicians have been stupendous,” Young effuses. “I think on the first album [Lifesigns] we were very progressive. On the second [Cardington] it was a mixture of progressive rock and a slightly poppier edge, and I thought we brought that into this album but also incorporated some jazz fusion, which I think works really well. There’s been quite a number of reviews, and the things I’ve really enjoyed is at one end somebody said it was like prog Steely Dan, and at the other end somebody said it’s like the new UK.”

Lyrically, Lifesigns want the listener to take the lead and form their own understanding of the words streaming into their ears. Although there’s no real common thread connecting Altitude’s themes, the band do have a knack of cutting through to the emotional bone. or example, on Shoreline, Young yearns: ‘Save me, save me/I don’t feel what you feel, there’s no one to help me at all.’ As he explains to Prog: “We try to put something out there that has a meaning. It’s up to people to make their own minds up. It’s a bit like if you put forward a news item without an opinion. We’re asking people to make their own opinion from the lyrics. It’s a great way of involving the listener.

“I also feel there’s a great therapy with music, there’s an element of healing that can come from music. We’ve found generally over time that’s what our albums have done – there is an element of a feel-good factor.”

Lifesigns’ own genesis, however, can be traced back – like so many things – to

a blether in a pub. It was more than a decade ago now that Young opined that progressive music back then was “treading water” and in return was encouraged to put his money where his mouth was and do better.

Never one to turn down a challenge, the musician recruited sound engineer and producer Rispin, bass maestro Nick Beggs and drummer Frosty Beedle, whose CV includes bringing the beats to Cutting Crew and stints alongside Boy George and Sinéad O’Connor – and Lifesigns were born.

Their self-titled debut, released in 2013, enjoyed guest cameos from prog stalwarts Steve Hackett, Jakko Jakszyk and Focus’ Thijs van Leer. Some line-up changes, a live DVD and second studio album Cardington followed.

“We’ve always recognised that because we’re all professional musicians, people have other day jobs,” Young says. “So if something comes in that’s going to be more lucrative and will pay the mortgage, we fully understand that. If we can roll with that, great, then if it’s too much it’s no problem, we can move forward. There’s been an element of a revolving door, but only when it’s necessary.”

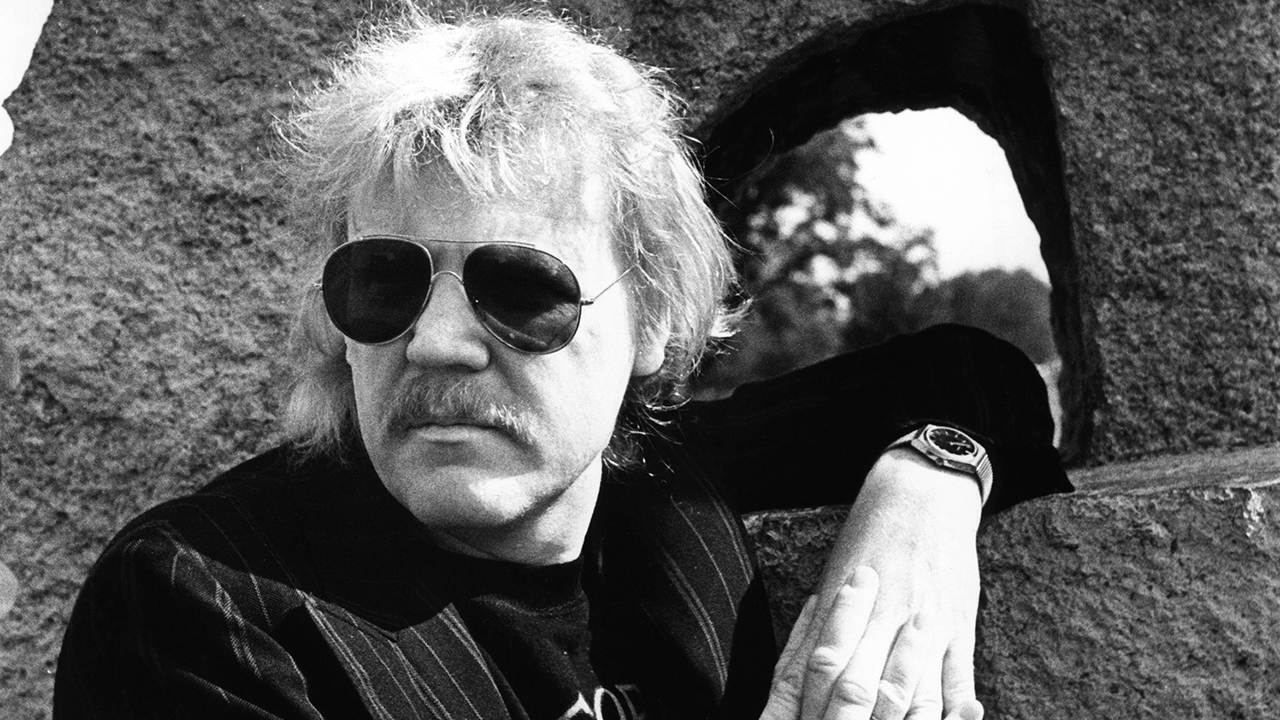

The current line-up has tangible pedigree. Poole played bass with Cardiacs for more than a decade, Bainbridge co-founded Iona and has racked up appearances with Robert Fripp, Neal Morse and Jack Bruce, Rispin has done sound for ELP and Fish, and Csörsz has performed with Quincy Jones and The Flower Kings.

Caught your breath yet? Young himself has history too; he’s played with Scorpions, did session work for Steeleye Span, performed with Asia and John Wetton, worked with Jon Anderson and Strawbs and continues to form part of Bonnie Tyler’s live band. Lifesigns, though, is where his musical heart lies.

So how does playing in Lifesigns compare with performing with acts like Total Eclipse Of The Heart singer Tyler? “With the generation that came up behind the 70s generation, quite a lot of us became session [musicians] that moved through various different artists,” he says.

“But in a way it meant that we couldn’t do what we do. Robert Fripp said to me once, ‘Your only crime, John, was that you were born five years too late.’ I think that’s probably a good quote for a lot of artists from my age group. Because they generally had to work with other people rather than doing things for themselves, because that horse had already gone in terms of record company money and that kind of thing.”

One unusual highlight in Young’s résumé is reaching No.3 in the Italian charts with an album he recorded with singer-songwriter Lucio Battisti in 1990.

“I’d never heard of him,” he laughs. “[La Sposa Occidentale] was in the Top 10 in Italy, but I still was none the wiser. It was quite funny when I suddenly realised who this guy was. The Bob Dylan of Italy, basically. It was a great honour to be involved.”

Reflecting Lifesigns’ tasteful take on prog, Young says he isn’t generally attracted to

the flamboyant end of the progressive spectrum, and he believes composition is his forte rather than playing.

“A lot of people would say to me, ‘You’ve never written a good song because you’ve never had a hit.’ That’s the way a lot of people see music. It’s probably one of the reasons why I like the progressive scene and things around it more, it’s because it’s more involved, it pulls you in more.”

Prog speaks with Young not long after the release of Altitude. It’s gone as well as can be without any gigs to promote it, and there’s been a stream of positive reviews. But a glance at Lifesigns’ Facebook page showed that a couple of fans weren’t too keen on the price the band chose to sell their vinyl and CD at – £30 and £20 respectively, although each comes with a digital download.

These figures might seem pricey, but Young makes a persuasive argument: “I think with the way streaming goes and everything else, there’s gradual expectancy from everyone that music should be free. I think that’s so dangerous. I think for anything to survive, you have to have value.

“When I was a kid you used to save up all week to get the vinyl. If you look at inflation, a CD now should be £46.50. But it isn’t. The thing is that it’s actually three to four cups of coffee, but a CD can last you a lifetime. So is that not of value? Does it not give you more than those three cups of coffee? I think there’s an element of dumbing down of the whole music scene, and to an extent unless we put culture back in there, and give it a value, then people are going to stop wanting to make music. If somebody comes to me and says, ‘Well, it’s too expensive’, then don’t buy it, or get the download, which is half the price.

“We’re not churning out pop music, we’re not spending an afternoon making a record and then just throwing it out with everything else. We’re making something that’s really valuable from our point of view, and we’re taking a long time to make sure it’s as good as we can possibly make it. So is that not then worth something?”

Lifesigns do have four songs on Spotify – a taster, if you will – to entice people to then buy the physical product.

“We’re there if you want to go and have a listen, but we’re not going to give you everything. Why would we give it away? I don’t have a problem with streaming if that’s what people want to use. It’s not so much the technology I’m bothered about, it’s the price that’s been put on it.”

Don’t expect to find Lifesigns organising any online gigs soon either. The geography of their members rules out any band get-togethers. With the hurdles Brexit will throw up around touring Europe, it remains to be seen what steps Lifesigns will take next. But now Altitude is in their arsenal, Prog expects them to take flight when the time is right.

“I think with regards to playing live, for me personally, I’m just waiting to see how the dust settles,” Young says of the future.

“I’ve seen so many people cancel so many tours and gigs, and I don’t really want to have to go through all that. I would say that I do hope the doors will open and there will be a flood of enquiries because everybody has been so starved for such a long time.”

A writer for Prog magazine since 2014, armed with a particular taste for the darker side of rock. The dayjob is local news, so writing about the music on the side keeps things exciting - especially when Chris is based in the wild norths of Scotland. Previous bylines include national newspapers and magazines.