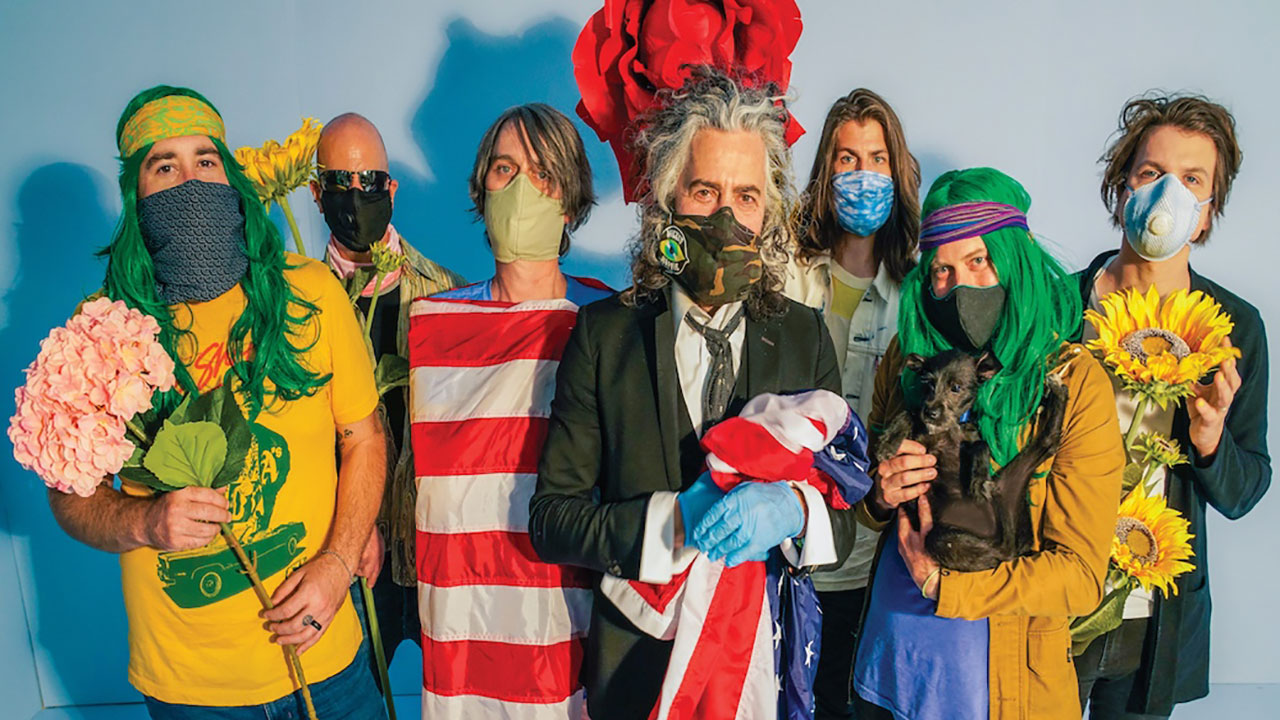

The Flaming Lips on prog rock, drugs and writing six hour songs

The Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne opens up on his love of Yes, ELP, Rick Wakeman and more

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

“Their song, Bad Days, from the Batman Forever soundtrack, was one of the first Flaming Lips tracks I heard when I was 11 years old,” recalls Kevin Parker of Australian prog-psych explorers Tame Impala. “Then I saw them live in Japan a few years ago and they blew my tits off. I’ve been a slave ever since. Are they a modern prog band? Definitely, yes. A 21st-century Crimson, Floyd or Yes? I don’t think they’re a 21st-century anything. They’re in a league of their own.”

The Tame Impala frontman is probably right. In 2011 alone, the Flaming Lips – approaching the 30th year of their so-called “accidental career” – did something strange and different every month, including (deep breath): issuing a track titled Two Blobs Fucking, comprising 12 separate pieces on YouTube that had to be played simultaneously to be heard as the band intended; releasing the Gummy Song Skull EP, a seven-pound skull made of gelatinous material containing a flash drive with four songs; presenting a six-hour song titled 6 Hour Song (Found A Star On The Ground) as part of a package called the Strobo Trip toy; making available a 24-hour track called 7 Skies H3 that plays live on a never-ending audio stream, one that you could buy – for $5,000! – as a limited-edition hard drive encased in an actual human skull; and performing the whole of Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side Of The Moon live at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, an album they covered in its entirety and released two years before.

As if that wasn’t enough, they recently broke rapper Jay-Z’s record for the most gigs played in 24-hour period, and they collected vials of blood from musicians (everyone from Ke$ha to Chris Martin, Nick Cave to Yoko Ono) for a 2012 album of collaborations called Heady Fwends, and then pressed a limited run of vinyl featuring samples of the same.

If you take ‘prog’ to mean manic ambition, madcap adventure, and a no-holds-barred approach to putting seemingly unrealisable ideas into practice, surely The Flaming Lips are one of the proggest bands ever?

“There are so many great terms,” enthuses Wayne Coyne, the Lips frontman who, at 51, has the energy of a hyperactive child; despite – or perhaps because of – the fact that much of his work addresses mortality, dread and loss. “People sometimes call us psychedelic, but psychedelia means Syd Barrett and Jefferson Airplane, and we’re not that. What we do is completely wide open. That’s why we like to call what we do ‘punk rock’ – it’s about doing whatever you want.”

Ever since The Flaming Lips formed in Oklahoma in 1983, they have gone through numerous line-up and stylistic changes, but Coyne, together with co-founder and bassist Michael Ivins and multi-instrumentalist genius (and renowned drug addict) Steven Drozd, are the constants. So too is the band’s commitment to freak-out music that has, if anything, become more far-out the longer they’ve gone on. The success of 1999’s The Soft Bulletin and 2002’s Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots hasn’t made the Lips any likelier to kowtow to commercial pressures. But then Coyne learned about pursuing one vision from the masters.

“I discovered Yes when Roundabout [from 1971’s Fragile] came out,” he recalls. “At that point nobody really knew how weird or how proggy they were going to get three or four records down the road. I saw them live, too. I liked the care they would put into making the songs sound like the recorded versions. And I love the way Jon Anderson sings – I wish I could sing as good as he does.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

While recognising why connections are made between Flaming Lips and prog bands such as King Crimson, Pink Floyd, Genesis and Queen (whose Bohemian Rhapsody they covered for a tribute album), he also sees links with post-rock and krautrock bands, especially on 6 Hour Song.

“When you make something that lasts for six hours, it can go anywhere stylistically,” he reasons. “There might be elements that remind you of Genesis without us being aware of it. But for me, Genesis had no element of punk rock about them. There has to be something ‘retarded’ in it for it to appeal to me. That’s what I like about Yes – Chris Squire’s crazy fucking distorted and freaky bass. And Jon Anderson is a funny, unique singer. He’s got a quirk, making it feel as though he’s doing his own thing. That’s punk rock.”

How about ELP? Their technoflash and pyrotechnical virtuosity is, in a perverse way, “punk rock”, isn’t it?

“You’re right!” he says. “That’s one of the reasons I liked ELP – they were brash. And the way [Keith Emerson] would stab his organ with knives in his leather jacket. I loved that shit because it was retarded! The same as Rick Wakeman with his crazy cape. Those bands were fun and had personality. It was about more than just where the right notes were.”

The Flaming Lips’ increasingly elaborate packaging concepts, their attention to detail and the statements they make with every release have precedents as well. “We always thought Pink Floyd seemed involved in packaging and the way things

were released,” he says. “Even [The Beatles’] Sgt Pepper came out with cut-out buttons [badges], and The White Album came with posters.

“I wanted to create more of an art-world scenario,” he explains of his latest schemes, adding that he sees Radiohead as peers because they look for new ways to present their work. But it isn’t just ideas for their own sake, he argues. It’s about respecting the hardcore faithful.

“Radiohead never seem to run out of ideas, and if you’re a fan of theirs, you feel like they love you. It’s the same with us – we love you, and I really do mean that! It’s like with the the human skulls: ‘Oh my God, The Flaming Lips really do love us!’”

Yes, about those skulls, Wayne… “The 24-hour song is about death, and came inside an actual dead person’s skull,” he laughs. “That’s pretty insane. I didn’t realise I lived my whole life in Oklahoma where there’s a shop [Skull City] which sells human skulls. Every month the owner gets a new bundle from people donating their bodies to science or whatever. It smells pretty fucking hellacious in there. Put it this way: if it was in a David Lynch movie, you’d swear it was an exaggeration. He puts flesh-eating beetles in with the skulls and they get to work for a couple of weeks. Then they get washed and they’re ready. Like I say, it’s insane.

“People wander into the studio when we’re working on this stuff and they’re like, ‘What drugs are you taking? What could make you want to do this?’ But you want your ideas to be like a drug that you take as much as you can, so much so that you overdose on it. The worst thing in the world would be to be in a band who’s been making music for 30 years and it all fucking sounds the same. That would drive me crazy.”

There have been a couple of occasions – after their MTV hit She Don’t Use Jelly in the mid-90s and their Soft Bulletin/Yoshimi heyday – when The Flaming Lips could have coasted. But they always take the path of most resistance, whatever the cost.

“I stopped worrying about money a long time ago,” Coyne admits. “We’ve done many things for the money and, there’s so much psychic pain, we don’t do that any more. We want a reason to live. We’re not going to make another Yoshimi. "

Coyne doesn’t fear burn-out, but he does acknowledge that his relentless creativity “could easily burn other people out”. He also admits that he’s increasingly “drawn to the dark shit”.

What he has been able to do recently, he says, is “learn to listen”. “The Soft Bulletin and Yoshimi were made during the shock of discovery that things die,” he explains of a period during which he lost his mother to cancer and Steven Drozd became increasingly addicted to heroin. As a result, those albums were almost ecstatic. Now, though, Coyne wants to go “even more heavily into the internal world”.

“I want to challenge myself,” he says, “precisely because we’ve been successful. We’ve become free, even if that means free to fail. And I think I’ve become a person who really listens.”

Specifically, he’s been listening to Drozd. “Steven has been addicted to drugs now three different times, and the last period was last February,” he reveals. “It was really horrible, but I’d grown used to it ; this is the way he lives. That’s a different sort of despair to the one I felt when we were doing Yoshimi and Bulletin, where I was like, ‘My friend’s going to die – let’s find a solution.’

“So, I’d be in one studio with Bon Iver or Ke$ha [working on Heady Fwends] and Steven would be in the other, making music to appease a tortured thread in his mind. I’d walk down there and be like, ‘This is the scariest, bleakest, most suicidal music you’ve ever made.’ And he’d be like, ‘Yeah, whatever.’ So I listened, and I thought: ‘Let’s make music like that.’”

The result is The Flaming Lips’ 15th album, The Terror, due for release early next year. It is, decides Coyne, “My favourite of all the records we’ve ever made. Especially for Lips fans, it will be a great moment. I’m not sure a lot of people will understand it, but they will in time.”

After recent attempts to rewrite the rules about recording and releasing, packaging and promoting, Coyne says “[The Terror] contradicts everything we thought we were on the way to doing. That’s the power of listening.”

It will be a testament to Drozd – who is “clean” now, and hopefully for good – and his uncanny, unorthodox instrumental skills, which Coyne likens to Miles Davis circa Bitches Brew, and to The Flaming Lips’ enduring ability to find new things to say, and new ways to say them.

“We’re like fucking kids still discovering what to do next, and that’s amazing to me,” Coyne reflects. “Steven could so easily have said, ‘Life just doesn’t have the same zing for me if I’m not able to be high,’ and he’s completely the opposite now. He’s able to see the world in a way that he didn’t when he was on drugs. And I understand. Drugs are interesting. But the world is interesting too. You just have to be aware of it, and listen. I know that sounds hokey, but it’s true.”

Coyne understands that it’s the Lips’ refusal to toe the obvious line that makes them so appealing, not just to fans, but to other bands or artists. And Kevin Parker is a Lips believer to the end. “There’s no stopping Wayne,” says the Tame Impala frontman. “He’ll be doing this till the day he dies. Are we picking up the Lips’ baton? They haven’t dropped it yet!”

This article originally appeared in issue 30 of Prog Magazine.

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.