"The bank robber seemed like a nice bloke. Said he had all my albums": The story of the wild tour that sent Joe Cocker over the edge

The Beatles queued up to give Joe Cocker their songs, but drink, drugs and wild times on the infamous Mad Dogs & Englishmen touring circus almost finished him off

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Hotel de Rome, in the former East Berlin, is situated in the plushest part of Germany’s most sophisticated city. Once headquarters for the Dresdner Bank and high-ranking Nazi Party staff, it bears shrapnel scars from Allied bombing.

The building opens onto Bebelplatz, where the SA, SS and Hitler Youth burned ‘un-German’ books during the ‘Säuberung’ in May 1933. It’s only a stroll to Checkpoint Charlie, passing plenty of brutalist architecture and the Jewish Holocaust memorial.

What was once fascist is now all about fashion, as supermodels sashay through the hotel’s foyer during Berlin Fashion Week. The movie Run Lola Run was shot in and around the hotel, where the motto is: ‘What’s old stays old. What’s new is new.’

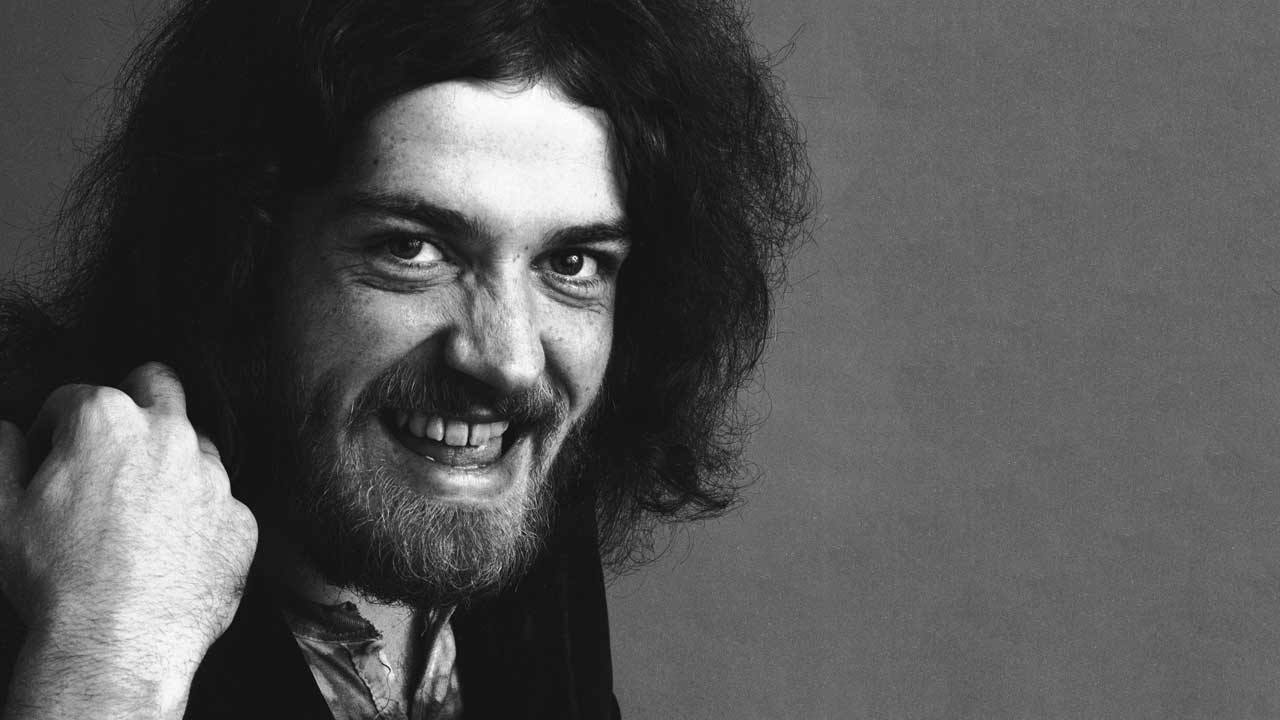

The Hotel de Rome is also Joe Cocker’s chosen port of call, indicating that the 68-year-old once known as the Sheffield Soul Shouter is no longer on his uppers. Virtually bankrupt in the mid-70s, he is now almost establishment: he’s got an OBE, he’s sung for the Queen, his interview suite is laid out with expensive chocolates and current craze macaroons. Luxury you can afford, Joe?

“Ha! Yes. Very good. The title of my only album for Warners, 1978. They sued me because it sold 300,000 copies! I’ve just got the rights back to that and my Sheffield Steel record, which is quite handy. I can’t get hold of my first three A&M albums, though, the ones that made the real money.”

These days Joe, who is stocky and exceptionally pleasant, lives on his Mad Dog ranch in Colorado, where he used to graze Watusi cattle but now sticks to growing tomatoes. Gratifyingly, he’s still got his Yorkshire accent, and he still follows Sheffield United, The Blades.

“Aye, the old Northern bit. I suppose my journey from 16-year-old gas fitter to today is a bit staggering. On my last trip to Australia, some old cat said: ‘You’ve led a life.’ Not a good one, mind. Not even a bad one. Just a life. Looking back, if I hadn’t made it I doubt I’d have stayed as a gas fitter. I’d still be singing in pubs and wondering what might have been.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Having left school at 15, Cocker served his music apprenticeship in local blues bands before a Decca scout whisked him to London in 1964 to record a cover of The Beatles’ I’ll Cry Instead for a single. Decca paid him precisely 10 shillings (50 pence in today’s currency) for his efforts, which featured the guitar talents of Big Jim Sullivan and Little Jimmy Page. But the single was a big flop, and Joe went home somewhat deflated.

“Decca were very professional. That’s why they dropped me,” he laughs. He left the Gas Board and went to work as a packer for WH Smith. He still sang, and he also drummed, which is how he developed his famous ‘disorientated hand jive’ tic.

“I never knew what to do with me hands,” Joe says. “Most people feel rhythm in their feet, but that was how I expressed myself. It looks daft, but I can’t help it.”

Salvation arrived via a meeting with fellow Sheffield lad Chris Stainton, and together they formed the fledgling Grease Band, whose demos landed on producer Denny Cordell’s desk. Fresh from success with The Moody Blues, The Move and Georgie Fame, the ebullient Cordell became the Grease Band’s mentor.

“Which was good news, because Sheffield wasn’t Liverpool or London. There was no rock scene. Our luck changed when we did a song called Marjorine, a very clever Chris demo which set the ball rolling.”

The Grease Band signed to Regal Zonophone in the UK, and built themselves a live reputation by word of mouth.

“Aye, we were a great band,” Cocker says. “We hit the ‘second wave’, after the ‘screamagers’ but before Led Zeppelin. I asked Jimmy Page if he’d join us in 1968 but he said: “Y’know Joe, I think I’ve got something a little heavier to do.” Oh, okay.”

Joe moved to a tiny flat off Sloane Square in London with his first wife, Eileen. He discovered hashish. “My consciousness was raised. Denny was a smoker, and he introduced me to LSD. We went to America in ’68 – that was an eye-opener. Each day was an adventure. I was so naïve. I got into a cab in New York once and the driver gave me a pill and I suddenly entered a Technicolor world. I’d had acid and listened to Hendrix, but never been outdoors on it.

"I liked the drugs, because they enhanced my enjoyment of music. Before that I’d only had a mono music system. Even my copy of Sgt. Pepper’s was mono. Suddenly this new world raced up on me. Maybe a bit too quick for a young guy – I’d just been a greaser with sideburns and tight trousers. It was a bloody big culture shock, and it went against my natural grain. When I was a kid in 1961, my dad stuck a newspaper in front of my nose with a story about Ray Charles being busted for heroin. ‘That bloke you like so much, Joe. Look at the state of him.’”

Very much a pint man, Cocker swapped Stones Bitter for a different type of stoner. That mono copy of Sgt. Pepper’s did the trick, however. Singing along to the album, he found himself drawn to vamping over With A Little Help My Friends. He made his own recording of the song in January ’68 with Page on guitar, Stainton on bass and Procol Harum’s BJ Wilson on drums, with dynamic vocal assistance from Rosetta Hightower. On Cocker’s version, Ringo Starr’s childlike singsong tempo was changed radically. Released as a single, it soared to No.1.

“The day it happened, I got a telegram,” says Cocker. ‘THANKS YOU ARE FAR TOO MUCH, JOHN AND PAUL.’ Then Apple Records placed an ad in the music press, congratulating me. What a plug!”

Anointed by the ultimate rock divinity, Cocker became a sensation, destroying British audiences and tearing America apart, even though his first album, named after the hit, sat in the can for a year before it was released. A superstar with one smash under his belt, Cocker entered a world where Beatles acetates were dropped off at Cordell’s office by limousine, long before the public would hear them.

In the summer of ’69 he was summoned to Paul McCartney’s house. “I was told: ‘Get here at 3pm on the dot.’ But I got there at 3.05. McCartney’s housekeeper, an old cockney woman, came to the door and said: ‘’E’s gone art. ’E was waitin’ for some man, but ’e’s never showed up. Go away.’”

Joe was more punctual a few weeks later when he was invited to the Apple building on Savile Row. “They stuck me in a room for an hour with nothing to look at but carpet. Eventually Paul turned up. He played me the medley from Abbey Road: Golden Slumbers and Carry That Weight. I was all ears until he said: ‘You can’t have ’em. You can have this, though.’ He played me She Came In Through The Bathroom Window.

"I was floating on the ceiling when George Harrison walked in shortly after. He played me Old Brown Shoe. By now I was getting a bit fussy, so I said: ‘I can’t see myself singing that.’ George played me three other songs and seemed a bit miffed. ‘The Beatles will never use these. I’ve got this one called Something. I wrote it for Jackie Lomax, and I wanted Ray Charles to sing it. You might as well have it.’ He actually played and sang it for me. I was gobsmacked.”

Even though he couldn’t release these beauties until his second album, 1969’s Joe Cocker!, both tracks were aired extensively on pirate radio. “It was a big deal for me. I remember George being so mad that John and Paul wouldn’t bother with his stuff. He thought it was touch and go that Something would get onto Abbey Road. ‘I doubt they’ll use it,’ he said.”

Those three Fab gifts served Cocker well. Just before his life-changing performance at the Woodstock festival, he played the Whisky A Go Go in Los Angeles. During his show-stopping rendition of With A Little Help From My Friends, a nubile admirer was hoisted on to her companion’s shoulders. She then proceeded to unzip Cocker’s jeans and give him a blow job in front of the entire audience. According to the Rolling Stone reviewer John Mendelsohn, ‘He gave the scream of his career as she worked the Cocker cock with considerable fervour.’

Joe recalls: “Jimi Hendrix was in the audience that night, sitting in a dark booth with a lot of groupies. I was just doing my thing when this lady… er, appeared. After the show I met Hendrix, and he was laughing his head off because he’d put her up to it.” He tried not to sing out of key.

Cocker arrived at Woodstock in a private chopper; the Grease Band slummed it in a military helicopter. They’d dropped acid and were feeling decidedly ill. Flying over the site, Chris Stainton opened the ’copter’s door and threw up over the crowd below. For Cocker, his arrival “was a real wow. I’d played to festival crowds of 50,000 that summer [notably Denver Pop], but all I could see were these white dots stretching to the horizon. I said to the pilot: ‘What the fuck’s that down there?’ He replied: ‘That’s people. And that’s where you’re playing, son.’”

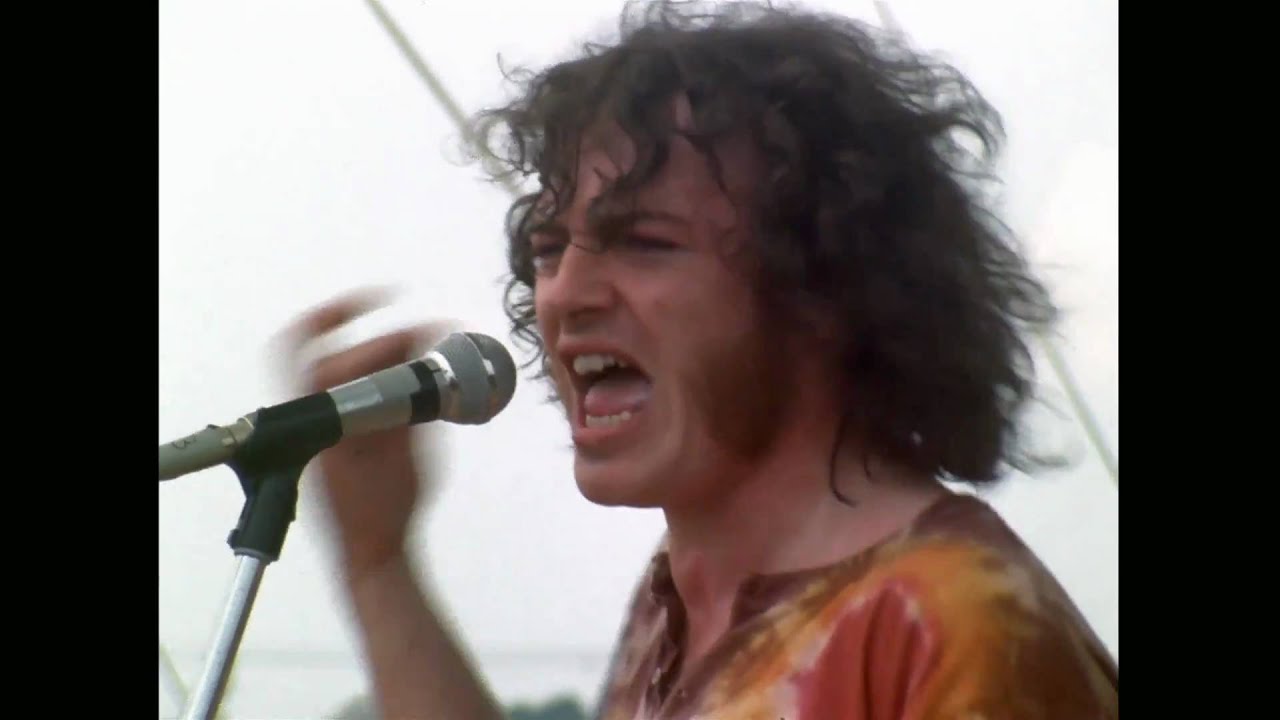

Cocker thought his Woodstock performance was “okay. Not the greatest. Santana did the best set. My abiding memory is how good the stage was. Usually they were wonky and dangerous, but this was a good professional job. “Were we epic? I dunno. We got some nice footage for memories,” he says, referring to Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 concert movie, Woodstock. “I was wearing a tie-dyed shirt, and when I took it off after, the colours had stained my chest in the exact same pattern.”

Having registered in the memory banks of 650,000 people at Woodstock and followed that with a triumphant show at the Isle of Wight, Cocker kept on touring into early 1970, flogging his sweat-drenched act into the ground before collapsing with exhaustion in Los Angeles.

With both his albums sitting pretty in the charts and his face on the cover of the first post-Woodstock edition of Rolling Stone, he felt a rest was on the cards. It wasn’t. Manager Dee Anthony called him up and told Joe he was booked to go straight back on the road; promoters are all in place. And no arguments, or you’ll be sued. And it starts in eight days’ time: a seven-week tour, 48 nights, 52 cities. Thank you.

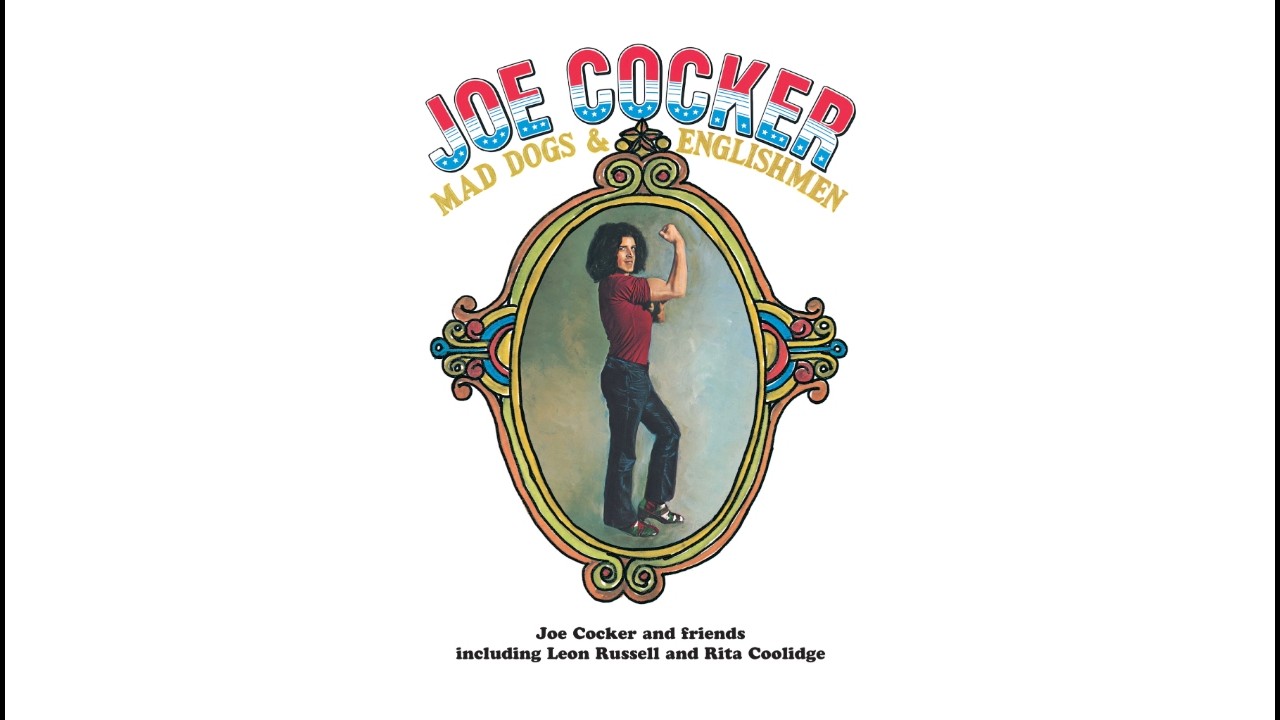

With the Grease Band back in London, Cocker panicked. Cordell suggested he call up Leon Russell, who had co-produced his recent album and provided the fine Delta Lady. Russell got out his phone book. Within days he’d assembled a 25-piece band, including three drummers, a horn section and a 10-strong choir of wailing ladies, featuring Rita Coolidge and Claudia Lennear.

With a support cast of management, techs and band dogs, the Mad Dogs And Englishmen – so christened by Cordell – were ready to rehearse at Russell’s house. However, Cocker did not realise that his contract required him to bankroll the venture. There was a film crew coming along too, and Joe was to pay for that as well. Didn’t he read the small print?

The director of the subsequent Mad Dogs documentary, Pierre Adidge, recalled: “It was no ordinary tour. They brought together the finest musicians in Hollywood, who all went because they wanted to go, because they wanted to be a part of this whole giant effort. They wanted to be together through their music.” Budget? Worry about that later.

Throughout the Mad Dogs episode, Cocker got more and more wasted.

“At first it was a family thing,” he recalls. “We were all shacking up in cheap motels; we had a cheap bus and a cheap plane. I wanted a much smaller group, but Leon was very persuasive. I got the blame for breaking up Bonnie And Delaney, because we took half their band. I didn’t even know who they were, but that got nasty. Yet it was irresistible. At Leon’s pad the scene was wall-to-wall women running around naked. Seemed like we were going to have some amazing times. They’d float in and out. Leon had his Tulsa connection, so he had a web of women on call. There were an awful lot of groupies,” he chuckles.

When the euphoria wore off, Cocker began to have doubts about Russell’s motives. “He became difficult. He got a bit strange. I felt lumbered because the other guys were getting completely wrecked. I was too, but I was doing all the promotion. Leon said: ‘Oh, you get the pleasure of doing all that.’ And I got involved in some crazy love affairs. Rita and Leon had a thing going on, and then she was sleeping with a couple of the drummers. Then I had a dalliance with her,” Cocker smiles.

“This was just before she hooked up with Kris Kristofferson. It was mad.”

Coolidge, the subject of Russell’s song Delta Lady, was rock chick of the moment. Ostensibly, she was still an item with a besotted Stephen Stills, although Graham Nash was often in her boudoir. Stills christened her The Raven; his magnificent debut solo album that year was an open letter to her. Love The One You’re With, Cherokee, Black Queen: they were all about lovely Rita. Laughing from the sidelines, David Crosby wrote another Coolidge anthem, Cowboy Movie, which referred to her as ‘The Indian girl… the heartbreaker.’

Mad Dogs drummer Jim Gordon was fanatically jealous of Coolidge’s liaisons. One night he flew into a rage and punched her in the face. Although she said it was out of character, Coolidge was distraught. The Mad Dogs were also getting twitchy. Gordon had started “hearing voices”, and would sometimes stop proceedings by telling the others: “You’re the devil… you’re messing with my time.”

Tensions were running high in the Mad Dogs camp. Cocker noticed how Russell, despite his own talent, had become envious and grouchy, and began to muscle his way up the pecking order. The man who’d started out like his brother suddenly “took over the whole show, became like a slave master,” recalls Cocker, who let it slide and went into his shell. He knew Leon was in constant pain and limping from a recent motorcycle accident.

Even so, he started to get cheesed off with Russell’s insistence on pre-show communal meals, communal sex and gang-style sermons, in which the Mad Dogs held hands and praised the Lord, before proceeding to get utterly wankered. “It was a bit embarrassing.”

The tour itself was an unwieldy shambles. Cocker often didn’t know the lyrics and clammed up, until Russell told him: “Doesn’t matter, man. Just sing what you like.” So he did.

Many of the band members were serious heroin users. Not just heroin, either: cocaine, pills, acid and booze were everywhere. The hard-core would gather together, all beards and top hats and ‘How y’all doin’?’, and do speedballs – deadly mixtures of smack, amphetamines, downers and coke. Then they’d drink Kentucky dry. Needless to say quite a few them are now dead – or in psychiatric hospitals.

“Whenever I see Jim Keltner, like I did in LA recently,” Cocker says, “he always says: ‘Man, that was some big, long, crazy party. How the fuck did we ever get home?’ It was a bit too crazy. I was saddest about some of the ladies who died, like big Emily Smith. Anyway, once it was over, Leon and the rest all left, probably the next day, and moved on to the Rolling Stones and Derek And The Dominos, and they kept on partying.”

Party they certainly did. Teaming up with Eric Clapton and bass player Carl Radle, drummer Gordon found kindred spirits in Derek And The Dominos, and was willing to match them on nights of heroin, liquor, coke, Mandrax and junk food. They were undoubtedly great musicians – Clapton described them as “absolutely brilliant, the most powerful rhythm section I have ever played with. Jimmy Gordon is the greatest rock’n’roll drummer I have ever played with. I think it’s true, beyond anybody.”

Later, in 1983, Gordon murdered his own mother during a psychotic episode. But that’s another story.

Despite the monumental excesses of the staggering Mad Dogs’ cast of Okies, Texans, good ol’ Tennessee mountain boys and equally flakey southern girls, engineer Glyn Johns rescued some tapes from their shows at the Fillmore East for a sprawling but hugely successful double live album, 1970’s Mad Dogs And Englishmen, the sleeve notes of which promised that “all elements of the truth are here”.

They certainly were in the movie: Cocker was interviewed backstage after one of the Dogs’ eight nights at the Fillmore West, and while various musicians are seen imbibing narcotics – what Russell referred to as “everyone bringing their own diversions with them, so they won’t really be away from their normal lives” – Cocker seems isolated and scared. Singing, he says, is “a release” from all the anger and frustration welling up inside him. “If I didn’t have singing I probably would have murdered somebody.” But still he’s an ordinary Joe – thankful for what he’s got, and mindful about where he came from.

Cocker was wiped out physically, and soon financially, as the Mad Dogs And Englishmen royalties were clawed back to pay for the tour’s considerable expenses. He settled in Los Angeles during summer of 1970, and began to hit the bottle. “I’d never really done much hard liquor before, because I was a pints man. I used to drink tons of beer – 10 pints a night, easy.” Now, without his fellow Mad Dogs, the Englishman let himself get rabid. “I overdid it for a year,” he said at the time. “You can forget about your music and start worrying about different things for so long. I just stepped out of it for too long. I think I almost forgot what rock’n’roll was all about.”

Joe seemed to have been bled dry by a business that he didn’t really understand. He also lacked the cynicism to cope with the down-side, once the hangers-on had left town. He didn’t eat, because he thought you had to stay thin to pull the chicks, but his personal life was in such disarray that that was hardly on the agenda.

The reviews for the Mad Dogs album weren’t great either. All that press, all that promotion, and then Rolling Stone slaughtered the vinyl. Even Robert Christgau, the eminent critic who had championed Joe’s cause, seemed to be damning him with faint praise when he pointed out that Cocker “is gruff and vulgar, perhaps a touch too self-involved, but his steady strength rectifies his excesses. He is the best of the male rock interpreters, as good in his way as Janis Joplin is in hers.”

Except that Joplin was dead. And as Cocker frequently told people: “I fully expect to be the next casualty myself. Why not? Everyone else thinks I will be."

Racked and ruined, Cocker returned to Sheffield. On arrival, his family was so aghast at his condition they hospitalised him. He chilled for a while: rode his motorbike along Snake Pass. He even considered taking his HGV licence so he could drive a lorry for a living. Armed with his next album advance, he went back to London and rented a flat in Shepherd’s Bush. Bad move.

“I started taking heroin seriously, even though I’d thought it was the big taboo. I flirted with addiction, but I couldn’t handle it on that level. It was too powerful and intense. I never used the works, I snorted heroin. It made me feel fearless. I’d be driving from London to Sheffield with mates and be speeding like a lunatic down the motorway. They’d be terrified, shouting at me to slow down. I didn’t bat an eyelid.”

Things got sordid after he fell prey to local West London dealers who descended on his pad. He walked the streets carrying ounces of cocaine on their behalf, and was constantly worried about his next bag of smack. The dealers were vultures; Cocker would part with thousands of pounds for dope worth far less. “They had me by the balls.”

Returning to recording his third studio album with Denny Cordell, Cocker found that much of his fame had evaporated. Unfortunately the bills were coming in for the Mad Dogs tour and movie. He was in hideous debt.

So he went back on the road in 1972. In Australia he was busted for weed and offering to take on 10 members of the Adelaide constabulary. He followed that by getting arrested again in Melbourne for causing a brawl at the Commodore Château Hotel, and spent a night in the clink.

“They put me in a cell with a bank robber, and an Aborigine who was alleged to have murdered someone. The bank robber seemed like a nice bloke. Said he had all my albums.”

The authorities gave Cocker four hours to leave the country.

He started telling those who’d listen that he was writing The Joe Cocker Book Of Drugs. But he wasn’t laughing. “I was drinking vast amounts, and it never seemed to touch the sides. Eventually I started going through alcoholic agonies. I was sick on stage, and the days afterwards were terrible. Drink became like heroin. It took the kind of toll where I was obsessed to make sure that I had enough left to get me through the day. And thanks to the mini-bar, I did. It wasn’t a good idea to drink before show time, but I made up for it afterwards.”

His biggest engagement in England that year was headlining the Crystal Palace Garden Party 3, in June 1972. Even though he kicked up the dust, Joe apologised for cutting his set short, explaining to the crowd that he had to get back to West London for ‘an appointment’.

His third studio album, Something To Say (titled Joe Cocker in America) was dutiful stuff. He hated it. He told one interviewer: “I don’t know why I’m here, really. I’ve got nothing to say about this album. I’ve got nothing to say about anything, really.”

He was seriously miffed that A&M had started promoting him as ‘Cocker Rock’. Life magazine’s assertion that he had “The voice of all those blind criers and crazy beggars and maimed men who summon up a strength we’ll never know – to bawl out their souls in the streets,” sounded a more accurate description, if too close for comfort.

Cocker now became a prima donna diva, always on the comeback. During his cocaine years, he managed another hit when You Are So Beautiful reached No.5 on the US Billboard chart. But he could still blow it big-time. Performing in Los Angeles in 1974, he threw up again on stage and suffered the performer’s ultimate nightmare.

“Somebody should have kept an eye on me,” Cocker said. “But some dealer found me backstage and filled me up with cocaine. I hadn’t performed live in a couple of years. I drank a whole bottle of brandy, and then went out and got through two songs, and then I sat down on stage with a total mental block.

“Everyone just sort of closed the curtains and said goodnight. That was supposed to be my big return. It was a bit sad.”

In the ensuing years Cocker was always active, although his albums became more mainstream as he slowed down and aged. Following a disastrous management period with Michael Lang, one of the co-founders of the Woodstock festival, handling his affairs, Joe received more scrupulous advice and was subsequently resurrected. He remarried, and enjoyed a worldwide hit single with his duet with Jennifer Warnes, the preposterously gloopy Up Where We Belong.

Thanks to the song’s inclusion on the soundtrack of the Richard Gere-starring film An Officer And A Gentleman and an accompanying Academy Award, Joe was establishment now. He got the Don Was production makeover for his 1996 album Organic. He played for President Bush’s daughter, and sang at the Queen’s 2002 Party At The Palace. According to his manager, he gave up drinking and smoking 10 years ago. “So he’s healthier. Back then he wasn’t well. It was often touch and go getting him to his concerts. If he hadn’t stopped he wouldn’t be here now.”

His latest album, Fire It Up, may be his last, he says. “It costs a fortune [to make an album], and that’s my two-album deal with Columbia up anyway. I’ve got a good feeling about it, but the last one [2010’s Hard Knocks] bombed in the UK. Maybe they don’t like me any more. I’m not sure about the future. I wonder: do I have to make records? I still like playing live. My agent wants me to play that festival, the Isle of Man.”

Isle of Wight, even? “

Oh, God. Yeah.” he laughs. “I’m so shagged out.”

But Joe Cocker will get by, with a little help from his friends.

This feature first appeared in Classic Rock 181, published in March 2013. Cocker passed away from lung cancer in 2014, and was posthumously welcomed into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2025. To mark his induction, the tour film of Mad Dogs & Englishmen was made free to watch on YouTube.

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.