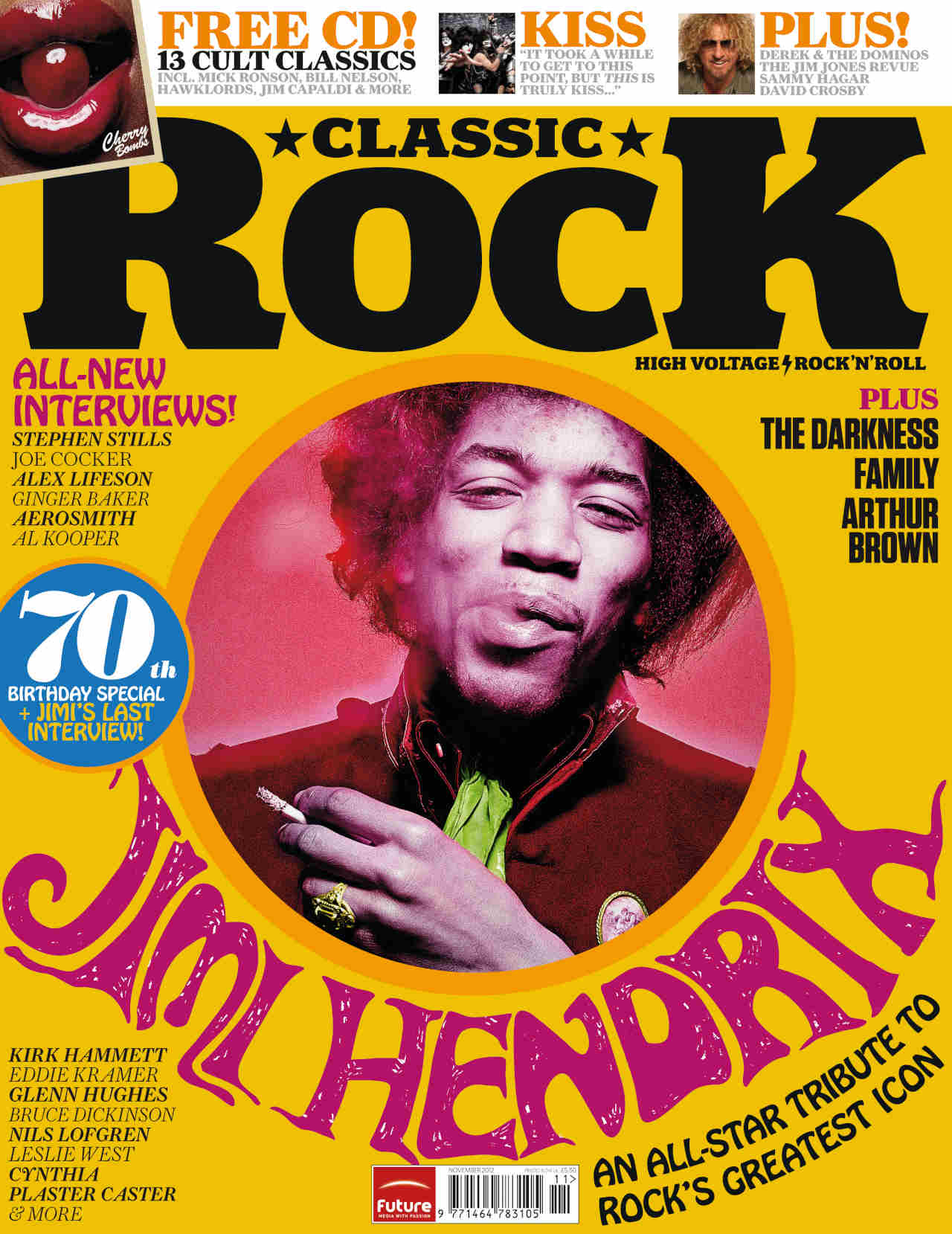

“You could never call us pretentious. We were a rock’n’roll band. A rock’n’roll band that liked to experiment”: The wild story of Family, the British hellraisers that John Lennon loved and Middle America hated

Prog? Rock? Blues? Family were a square peg in the round hole of early 70s rock

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Family were one of the great cult bands of the late 60s and early 70s. Spanning the worlds of rock, prog and blues, the notched up a string of hits before imploding before they ever truly became massive. In 2012, ahead of their reunion the following year, Classic Rock sat spoke to the surviving members of the band to look back on a story of missed opportunities and thwarted ambitio.n.

In the slightly surreal world of Family, it seems almost fitting to start their story at the end: October 13, 1973, the Holiday Inn, Leicester, a few hours after the band’s last ever show at Leicester Polytechnic.

It was a big send-off, the grand finale, the last gig of a sold-out UK tour, in front of a partisan home audience. It was good, says Roger Chapman, the band’s irrepressible lead singer. “Really good.” But the after-show party that night at the Holiday Inn? “Well,” he laughs – which he does heartily and often – “that was even better.”

Jon Lord was there. As was Ralph McTell, ‘Whispering’ Bob Harris, John Peel; everyone from the band’s record company; footballers Frank Worthington and Lenny Glover from Leicester City; an assortment of nubile young ladies. There was beer, wine, Champagne, illegal substances; dark corners and dodgy behaviour. It was that kind of night.

As the party spilled over into the pool area, a man appeared, wearing deep-sea diving gear. He leapt into the pool and started throwing bubble bath around. The buffet table ended up in the deep end. There was a food fight. A couple of dozen rubber ducks floated from the pool into the hotel lobby on a wave of bubbles, debauchery and excess. The fun and chaos went on all night. Rob Townsend, Family’s drummer, left early when someone attempted to throw his pregnant wife into the pool.

It was like a wild, end-of-term party, Bob Harris remembers, “involving increasing nudity and general celebration. The party was eventually brought

to a halt by hotel management at around 5.30am, after many complaints.”

At 6am, staff at the Holiday Inn decided to stage a full fire drill. It was their revenge, says Chapman. “I can’t say I blame ’em,” he laughs. “But that was what it was like back then. We went for it. We were never the kind of band to do things by halves. We never did.”

A wise man once said that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. Which is where, today, you find Roger ‘Chappo’ Chapman. He’s a curmudgeonly old bugger. And that’s not us being uncharacteristically unkind, that’s him being characteristically blunt.

“My trouble,” he says, long fingers scratching a stubbly chin, “is that I get the hump. Always been the same. We can be playing somewhere, and everything will be going well, and then I’ll hear some arsehole shout something from the crowd and that’ll be it, I’ll be on one. Or maybe the lighting man will do something wrong, and that’ll set me off. I get mardy. It’s not a kind of rock star excess, I’ve always been like it. It’s just the way I am. Too late to change it now.”

Chapman turned 70 this year. He quite enjoyed it. “I’ve only ever felt slightly twitchy about my age once, when I was around 55, 56, and so many people said: ‘Oooh, soon be the big six-o, eh?’ that I was bloody relieved when I did finally reach 60.”

He looks well. Better than he deserves to look, being honest, for a man who has lived the life he has. The debauchery stopped a long time ago. He quit smoking 20 years ago. He stopped smoking weed after suffering a psychotic breakdown during a press conference in a Paris hotel room in the 70s.

“My body just gave up,” he recalls, “right in the middle of an interview with four or five journalists. I think they thought it was all part of my thing, you know, this weird act, the enigmatic English rock singer. It wasn’t. I remember sinking further and further down in my chair, and then not being able to get up.”

He should have been sent home to rest, the tour cancelled. Instead, he played the show that night. The rest of the band were never told.

Back then, he says, there wasn’t much he didn’t do. Dope, acid, speed, cocaine, heroin, pills, uppers, downers, it was no big deal. Everyone did it. You were considered a bit strange if you didn’t.

“I was lucky, though,” he says. “I could turn my back on it on the way that others couldn’t. I did drugs, yes, but I did them recreationally. I saw what it did to others, good friends, people I knew who couldn’t stop, and I know I’ve been very fortunate.”

The story of Family is one involving other-worldly musical creativity, excess, a stubborn insistence on doing things their own way, and commercial under-achievement. These things may, or may not, have been linked. “I have no regrets,” Chapman says bluntly. “We did things our way.”

It is the story of a working-class band who were working on building sites in Leicester one day, and attending swanky London parties with Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon the next.

“We moved from Leicester to a house behind the Kings Road in Chelsea. I remember going out for dinner one night to an Italian restaurant on the Fulham Road with actor Ben Carruthers [whose son, Dijon, went on to play drums in Megadeth]. He was in The Dirty Dozen, a big film at the time. He took something from his pocket and popped it in our champagne. ‘Here you go,’ he said. ‘This should liven things up a bit.’ That was my first acid trip. Did I like it? I must have done – I did it again and again.”

Born in Leicester in 1942, Chapman was raised by his grandparents. His dad left when he was two, his mum died when he was 13. Roger and his elder brother Tony were in and out of care. It was tough. Rock’n’roll, he says, kept him out of trouble.

He left school at 15. He told the careers advisor he wanted to go to art college to study painting. Instead they found him a job painting on building sites. At night, he sang in the local clubs. People told him he was good, that he could really sing. “You should join a band,” they said. So he did.

He joined The Xciters, who had a shy, young bass player called Ric Grech. Grech, whose Ukranian father had settled in Leicester after the war, was an introverted but highly talented musician who’d swapped violin (he was classically trained) for the bass guitar after hearing The Beatles.

Grech left The Xciters to join The Farinas, Leicester’s premier rock’n’roll band, led by brilliant young guitar player John ‘Charlie’ Whitney, and multi-instrumentalist Jim King, who also sang. When King switched from singing to harmonica and sax, the band needed a new singer. Grech took them to a building site in Leicester.

“I remember them coming to the site and asking me to join. I said yes straight away,” says Chapman. “I’d seen them. Everyone knew of The Farinas. They were a classy band.”

The Farinas became the Roaring Sixties, decked out in questionable double-breasted suits. “God only knows what we were thinking,” says Chapman. “We looked dreadful.” US impresario Kim Fowley, who recorded an early demo by them, liked the look, insisting they looked like The Family – a reference to the Chicago mobsters of the 1920s.

With the mobster suits soon ditched, they became Family. “I fucking hated it,” Chapman says. “I thought it was an awful name for a band. I did for a long time.”

Family signed a management deal with John Gilbert, son of film-maker Lewis Gilbert, who had directed Michael Caine in Alfie. Gilbert had ambition, drive and an impressive contacts list, but not what you might call the band’s best interests at heart.

In early ’68 they moved from Leicester to London, ditching drummer Harry Overnall and bringing in fellow Leicester lad Rob Townsend.

At 19, Townsend was the baby of the band. Nicknamed the Grapefruit Kid (“I played in pubs with bands, underage, and I couldn’t drink. I had grapefruit juice”), he eschewed the rock’n’roll lifestyle: “I know that period is generally regarded as a time of drugs and partying, but it wasn’t for me. I think I had a joint once, and I was sick everywhere, so that was pretty much it for me.”

Family signed a record deal with Warner Bros offshoot Reprise, and the band members shared a house behind the Kings Road. The management deal they signed ensured John Gilbert received 50 per cent of Family’s songwriting royalties from their first two albums. He still does to this day.

“Don’t get me started on that,” Chapman growls. “There’s a clause in the deal that says he gets half the royalties ‘in perpetuity’.”

They wouldn’t have known what that meant back then – if indeed they ever read it. Then, rock musicians paid scant attention to the paperwork. It was all about the music, man, and the vibes and the drugs and the parties and the chicks. Late-60s swinging London was a good time and place to be in an up-and-coming rock band.

“We’d stay in all day, smoking joints and writing songs, then we’d go out to a club, or some party, get back at 5am, sleep all day, get up, and then do it all over again. We were just kids from the provinces. We’d seen nothing like it. It was brilliant. We had the time of our lives.”

The band’s first album, Music In A Doll’s House, released in July 1968, was an ambitious and sometimes challenging listen, elevated by Chapman’s extreme, bleating vibrato. “This man’s voice could kill small game at 100 yards,” said one reviewer.

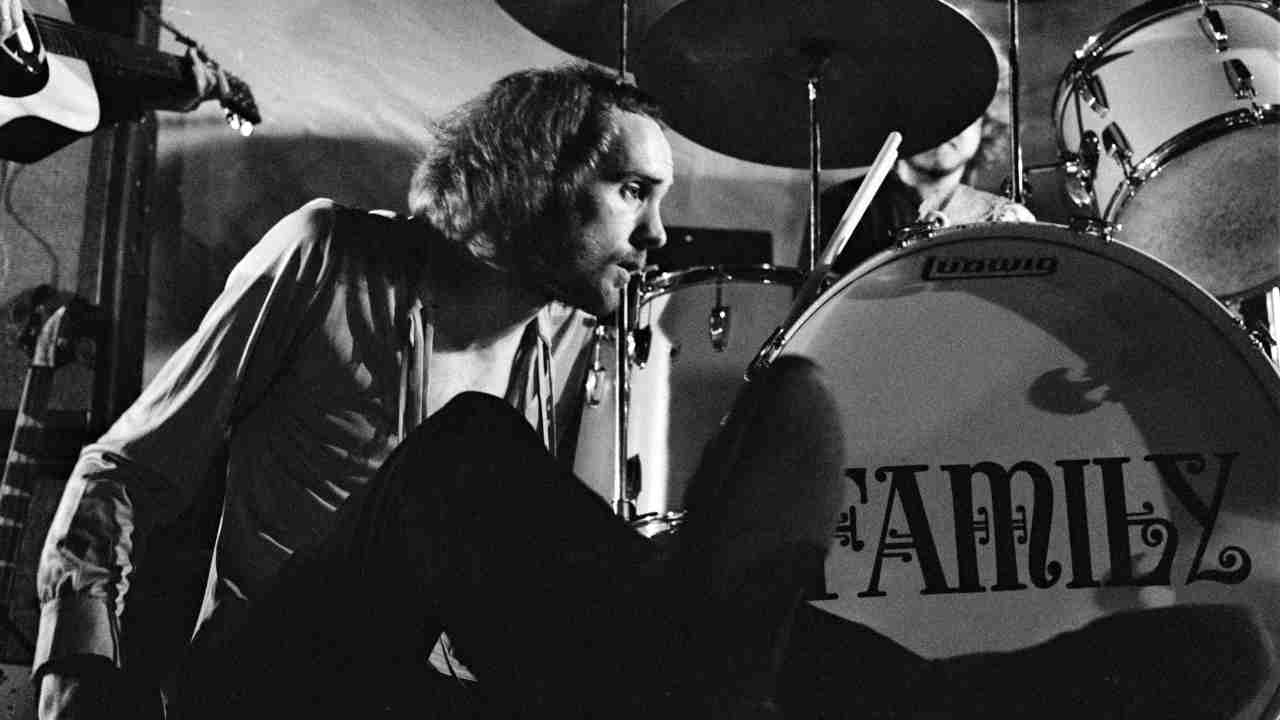

But it wasn’t just the vocals that set Family apart. It was Whitney’s tasteful guitar playing, Grech’s impressive bass and violin work, and Jim King’s all-round musical dexterity. Townsend nailed it all together with his distinctive drumming. Individually, they were good. Together, like all great bands, they were more than the sum of their impressive parts.

Produced by Traffic guitarist Dave Mason and engineered by Eddie Kramer at Olympic Studios in Barnes, south-west London, Doll’s House reached No.35 in the UK. Brimming with horns, Mellotron, violins, studio effects, other-worldly sounds and, on one track, the Tubby Hayes Orchestra, Family’s first album is the sound of the acid-drenched underground; five men pushing at the musical boundaries of the era, experimenting, sometimes nailing it, sometimes not, but daring to be different.

Critics said Family were progressive. And yet while the music was adventurous, it was never highbrow. “You could never call us pretentious. We were a rock’n’roll band,” says Chapman.

“A rock’n’roll band that liked to experiment.

“It was an incredible period of musical creativity, really. We were bursting with ideas. I remember we’d sit in the house we shared, and Charlie would pick up a guitar, strum a few chords, and I’d write the lyrics and the melody, and then Jim King would come in and take it somewhere else. And we’d write two, three songs a day like that.”

As well as vocals, on Doll’s House Chapman is credited with tenor saxophone. It was a lie, he admits.

“I couldn’t play the saxophone. I had one, and Jim tried to teach me, but I couldn’t play it. Jim picked one up and, I swear to God, he learned it in two weeks. I could parp out a few notes, but it would be a lie to say I could play it. I put it on the floor once during a rehearsal, and one of the PA speakers fell over and crushed it. The band were like: ‘Oh, Rog, your sax.’ But secretly I was relieved because it meant I wouldn’t have to play it again.”

Seven months after Doll’s House came Family Entertainment. Unusually for a second album, there was no pressure, says Chapman. “If there was, we didn’t feel it. We were just churning it out.”

Looking back, he says this period was the high-water mark of the band. During an interview in 1969, John Lennon singled out Family.

“Musically,” Lennon said, “they’re about the most interesting band out there.”

He was right. “For 18 months or so we were just couldn’t go wrong,” Chapman says. They were writing brilliant songs, and wooing audiences with their manic live performances. It was magical, and effortless. “We took it for granted, as if it would always be like that.” It wasn’t.

Their second album was a more straightforward affair than their debut. But it wasn’t meant to be. They were hoodwinked by their manager, says Chapman.

“We’d finished the album and we were on tour up north somewhere, so, in our absence, John Gilbert and producer Glyn Johns [Beatles/Stones/Led Zep] mixed the album. We hated it. The songs on there are good, but it all sounds a bit too smooth, a bit too ‘safe’.”

A bit too – whisper it – commercial. And Family were nothing if not wilfully uncommercial.

“We released a single, In My Own Time, and then we wouldn’t play it live because we thought that was selling out. We didn’t even put it on an album. We never liked playing [much later] our most popular song, Burlesque, because we thought we were being too commercial.” Stupid, he says. Brainless. “But there you go. If it was a mistake, at least it was ours, nobody else’s.”

Ric Grech especially was peeved at the smooth sound of the second album. “I remember him nagging at me about the bass on one song, and my vocals drowning him out. ‘Bloody hell, Ric,’ I said, ‘it’s not my fault. I was on tour in Leeds with you when it was mixed.’”

Family Entertainment reached No.6. Album opener The Weaver’s Answer, a moving lament about an old man nearing the end of his life, became the band’s signature song.

Family were building a formidable reputation, especially for their dynamic live performances. Later it would help them get big gigs like supporting the Stones in Hyde Park in 1969, and on the Isle of Wight Festival bill the same year and in 1970.

By early ’69 the buzz had spread to the States. Dates were booked there, beginning with a run of big shows at the Fillmore East in New York, arranged by big-shot US promoter Bill Graham.

April 8, 1969 should have marked the beginning of a glorious new chapter for Family. Instead it was a disaster, says Chapman.

“We were in a hotel in New York hotel, just by Central Park, and I remember John Gilbert and Ric Grech deep in conversation in the lobby,” the singer recalls.

Gilbert announced that Ric had something he wanted to say. Grech said he was leaving the band. Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Steve Winwood were forming a new group and they wanted him as their bass player. And, in fairness, who would have been able to turn down an offer like that?

“They’d known for weeks. But we were told on the day we were playing our first gig in New York!” Chapman exclaims, the exasperation still evident in his voice 40 years later.

Family were a thrilling live band. “I’m proud of the albums we did, but we always struggled to capture the real essence of the band, the way we sounded on stage,” says Chapman, who would whip the audience into a frenzy with his manic shape-throwing and trashing numerous tambourines against his mic stand.

That first night at the Fillmore, however, was awful. “Ric was so pissed, so stoned, that he could barely stand up. He was holding himself up on his bass amp for most of the gig,” says Chapman.

The singer was furious, and hurled his mic stand across the stage – to the side where Bill Graham stood watching. “I didn’t aim it at him,” he says. “It wasn’t deliberate. I was just on one.” But Graham took huge umbrage, marching round the venue tearing down Family posters and chastising the band for their lack of professionalism.

Chapman was made to finish the tour with his hands by his side; no tambourine, no theatrics, no personality. “It was terrible,” he says.

Later that week the band had all their equipment stolen. Chapman lost his passport en route to Canada, which meant all the Canadian shows had to be pulled. His visa was revoked. Everything that could go wrong did go wrong. Having set out with high hopes, they returned to England early, and without a bass player.

“Our card was marked after that,” he says. Success in the US always eluded them. “I put it all down to that first show and tour.”

Back home, the show had to go on, and it was the beginning of a relentless round of musical chairs for Family. John Weider, formerly of The Animals, was brought in on bass and violin to replace Grech, and they returned to Olympic to record their next album.

Before work even commenced, Jim King was shown the door for “erratic behaviour” – a common 1960s euphemism for drug problems. “You have to remember, Jim was always a bit left-field, brilliant but eccentric,” says Chapman. “Whatever substances you’re taking – and I’d guess that, for a long time, Ric and I were probably the worst – then you go your own way. By that time, let’s just say that Jim seemed to be further out on a limb than the rest of us.”

In came John Palmer on keyboards, synthesiser, flute and vibes. First, though, he needed a new name. “They refused to call me John, there were too many Johns in the band,” says Palmer. “So they called me Poli. I didn’t like it, but what can you do? You can’t pick your own nickname, can you?”

He’s been Poli ever since. “I think only my bank manager calls me John.” And besides, he says, it could have been worse. “When John Wetton joined two years later, they found out his middle name was Ken, so that was it: Ken. He bloody hated that.”

Parts for the new album that had been written for King’s sax were rewritten for Palmer’s flute. It gave Family a different dimension, an unexpected new direction. The album, A Song For Me, produced by the band this time, reached No.4 in the UK.

But the gap between the band’s two driving forces – Chapman and Whitney – was beginning to widen. “I was smoking weed, he was drinking whisky,” says Chapman. “The two things didn’t really go together.” Whitney was now writing more reflective, acoustic-style numbers with Weider. “I liked what they were doing, but it was too straight, too Joni Mitchell – and not Family.”

Anyway, Family’s fourth album, with one live side recorded at Croydon’s Fairfield Halls, and one studio side, was released in 1970. Overall, it was underwhelming. “I remember the recording equipment arrived at Croydon at 7pm that night,” says Palmer. “Mics were hastily taped here and there. It was done on an old eight-track – bass and violin on one track. It was rushed. And I think you can tell.”

With the revolving door marked ‘personnel’ continuing to turn, out went Weider and in came John ‘Ken’ Wetton, just as the band were recording their fifth album, Fearless.

“John [Wetton] was a good man, and a fine bass player,” says Chapman. “He was a good influence, I think, on the band. He took us in a different direction again.” Wetton lasted just a year, before he left to join King Crimson.

Bandstand, released in 1972, was a return to form for Family. Still far less experimental than the band’s early work, song for song it was one of their most consistent records. It also gave Family their last, and best-known, hit single, Burlesque.

After Wetton, Family’s next bass player was Jim Cregan, from soft rock band Stud. He was a guitarist, but he was joining on bass – a point that seemed to elude him at first, drummer Rob Townsend remembers.

“We offered him the job, and he said yes immediately. ‘It’s bass, though,’ we said, ‘not guitar.’ There was a pause, which was him realising it wasn’t what he thought it was. Then he said no. He rang back later that day and said: ‘Go on then, I’ll do it – as long as you teach me to play bass.’”

He mastered it in no time. “He was good,” says Townsend. “Not particularly flashy like Wetton or Ric, but rock solid.”

Bandstand was also Poli Palmer’s last album with Family. Today it’s still one of his favourites. “Some of the arrangements on there are good,” he says. “But I do remember we couldn’t think of a name for it, we didn’t have an idea. In the end our manager thought of the name. That had never happened before. I just thought it was kind of symbolic of the state we were in – a bit tired, creatively exhausted.”

In the autumn of 1972 Family began a US tour, supporting Elton John. This was where the band began to fall apart, says Townsend. Elton rarely had a day off. They played night after night, travelling huge distances from one state to another. They played to a million people in less than two months. It was a tough tour. The audience response was mixed.

Family did well in the more urbane east and west coast areas, but in other places it was a different story. “They just didn’t get us in the Midwest,” Palmer remembers. “It was fine in New York and LA and San Francisco. Everywhere else – and that’s a big area – we were met with a kind of quiet bemusement.”

The camaraderie was different, too. “The band had changed,” says Townsend. “It wasn’t these likely lads from Leicester any more, living in the same house. It was more of a business.”

Shortly after the Elton John tour had finished, Palmer became the latest band member to take the exit door. “It was time to go,” he says. “Family were an intense band. By that time, I think, we’d run out of intensity.”

In came keyboard player Tony Ashton, previously of Ashton, Gardner And Dyke, who’d had a Top 3 hit with The Resurrection Shuffle. By now Family was a shadow of its former self, and on its last legs. They released one more album, It’s Only A Movie, in ’73, which received lukewarm reviews, before succumbing to the inevitable.

“It was my favourite Family album,” says Townsend. “I know people talk about Doll’s House, but Doll’s House, to me, sounds like 1967; It’s Only A Movie, I think, is more timeless. Tony Ashton had come in and he was a piss-head, basically, but a great fun-time bloke to have around. We had a laugh. I enjoyed recording it. A couple of the previous albums, they were so laborious to record, but we did this so quickly and easily. The pressure was off.”

It’s Only A Movie wasn’t great box office and in October 1973 Family split. “I think we’d just all had enough,” says Roger Chapman. “We were tired, a bit stale. It wasn’t as creative as it once was. There were these little niggles and arguments, too. I don’t have many regrets about my time in Family but one of them is that we never really had any rows. No big, fucking clear-the-air shout-outs, which I think would have been better for us.” Instead, he says, there was just lingering resentment.

Chapman and Whitney went on to form Streetwalkers, with guitarist/vocalist Bobby Tench and a couple of former King Crimson men, among others. Between 1974 and 1977, and with a number of line-up changes, Streetwalkers released six albums. Today, that widening gap between Chapman and Whitney, who had once formed a potent songwriting partnership that was pivotal in Family’s early career, is so big that the two are not even close. “We don’t speak,” says Chapman. “We communicate by email, maybe twice a year. He lives in Greece. There’s nothing more to say… “We didn’t fall out. Not really. But… it’s complicated.”

Whitney went on to form Axis Point and country band Los Racketeeros. Poli Palmer played in Chapman’s solo band and worked with Pete Townshend, Linda Lewis and others. Rob Townsend turned down the chance to join Marc Bolan’s band and instead played drums with Medicine Head. Today he plays with The Blues Band and The Manfreds.

After Family, John Weider played on a number of records, and has released several solo albums. Jim Cregan played with Steve Harley/Cockney Rebel before finding big success for many years as bandleader, co-producer and co-writer for Rod Stewart. And you know about John Wetton’s adventures in Asia.

No one had heard much from Jim King since he left Family. He passed away in February 2012. Also no longer with us is Tony Ashton, who died of cancer in 2001. And Chapman? He’s still doing it. Of course. “I keep saying I’m going to retire,” he says, “and I mean it, too. I’m not just saying it. But then as long as I keep waking up at 4am with a tune in my head, I guess I still have to carry on.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 177 (October 2012)

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.